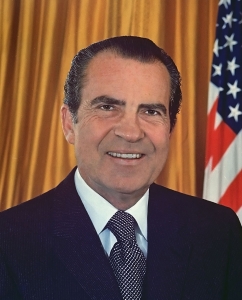

Richard M. Nixon (1969-1974): Going Through the Motions

This article is a part of our series From Lighthouses to Electric Chargers: A Presidential Series on Transportation Innovations

What is a historian to do when it becomes clear that the historical figure who accomplished so many positive things did so for the most selfish of reasons – to get re-elected – and not because he cared about the underlying policy much at all?

This is the situation we face with the domestic policy legacy of Richard M. Nixon. Although a culturally conservative Republican, his first term was a frenzy of progressive policy activity that stands up to anything that Lyndon Johnson. Barack Obama, or Joe Biden accomplished. (The National Environmental Policy Act. The Clean Air Act of 1972. The Noise Control Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act. Creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. The Occupational Safety and Health Act. The Consumer Product Safety Act. Supplemental Security Income. He even was the guy who signed Title IX for women in college sports. Plus a lot of more specific transportation acts, to be seen below.)

Nixon’s domestic policy was overseen by two men: future Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (Nixon’s advisor for Urban Affairs), and head of the Domestic Policy Council John Ehrlichman, a land-use lawyer from Seattle with a significant record in opposing sprawl.

Ehrlichman’s memoirs are a fascinating read. When Nixon went to Ehrlichman in summer 1962 to recruit him for his California gubernatorial campaign, Ehrlichman wrote that “Nixon and I talked about urban blight, the role of the State of California in land-use planning and how to clean up the air and the water. I catalogued the problems facing mayors and governors – highway location, school finance, historic preservation, urban renewal, parks and recreation – that he would be called upon to wrestle with…it was evident they interested him only as campaign issues.”

But Nixon knew that environmentalism was a popular philosophy on the rise, and that urban and suburban voters would be the difference in the 1972 elections. So he sought out to have a domestic agenda that could get him re-elected, delegated to his senior staff and the Cabinet Departments, and then spent most of his personal time on foreign affairs.

For Secretary of Transportation, Nixon named Massachusetts Governor John Volpe. One could be forgiven for assuming that Volpe was going to be a traditional highway guy – he ran a big construction company that built a lot of highways (along with being the prime construction contractor for the new DOT Building he would soon inhabit in mid-1969 in Washington DC), and he ran the Federal Highway Administration briefly under President Eisenhower. But he had his own ideas, which lined up well with Ehrlichman’s.

Before building its own highway agenda, the Nixon team had to deal with issues left over by the Johnson team– and on several key issues, they did so by simply adopting the proposals of the previous (Democratic) Administration

Airports and airways

There was widespread consensus in the late 1960s that the federal government was going to have to increase funding for air traffic control (“airways”) significantly in order to keep pace with the faster and more numerous planes being brought into service. At the same time there was significant funding pressure from Congress and states for more federal aid for airport development, particularly for the longer runways that the larger jets would need.

The Johnson Administration had proposed a three-part airport and airways plan to Congress in May 1968: an increase of airways spending by $250 million per year, conversion of much of the federal airport grants into federal loans, and an increase in aviation excise taxes to pay for it all (EC No. 1863, May 20, 1968). But the LBJ plan went nowhere in Congress, with Senator Mike Monroney (D-OK) telling White House staff that unless they deposited the tax increases in an aviation trust fund, instead of in the General Fund, aviation interests wouldn’t go along with it.

Upon taking office, Richard Nixon ordered a quick review of the problem, and then in June 1969 transmitted a revised version of the Johnson plan to Congress as his own, with the increased tax receipts to be held in a special “Designated Account” at Treasury. Congress converted the Designated Account into an Airport and Airways Trust Fund, made the airport grants more generous, and enacted the Airport and Airway Development Act into law in May 1970 (P.L. 91-258). That law set the stage for all national airspace development since then, and the Trust Fund is still in use as the primary means of supporting federal airport and air traffic control spending.

|

Proposed 1968-1970 Aviation User Tax Increases |

||||

| Existing | LBJ | Nixon | Enacted | |

| Law | Proposal | Proposal | Law | |

| Sales tax on domestic airfare | 5% | 8% | 8% | 8% |

| International enplanements | none | none | $3 | $3 |

| Freight waybill tax | none | 8% | 5% | 5% |

| General aviation gasoline | 3¢/gal. | 10¢/gal. | 9¢/gal. | 7¢/gal. |

| General aviation jet kerosene | none | 10¢/gal. | 9¢/gal. | 7¢/gal. |

| Tax receipts held in | Gen. Fund | Gen. Fund | “Designated Account” | Trust Fund |

Mass transit

With just five weeks to go in the Johnson Administration, DOT sent the Bureau of the Budget a draft proposal for a massive increase in federal mass transit funding, to be backed by a new Urban Mass Transportation Trust Fund. The bill called for annual mass transit funding to triple, from $200 million in 1970 to $600 million in 1974, offset by transferring the receipts from the existing federal sales tax on new automobiles from the General Fund to the new Trust Fund.

The Johnson Administration never formally submitted the bill to Congress, but the 1968 Republican Party Platform had called for using “a trust fund approach to transportation [to] speed the development of modern mass transportation systems,” and Nixon’s transportation transition team concurred. As did Volpe, who picked up the Johnson bill with relish.

After some internal back-and-forth (see “The Johnson-Nixon Mass Transit Bill of 1968-1969” for details), the White House backed off the demand for a trust fund and dedicated revenues, but added even more money and made it all guaranteed, up-front “contract authority” from the General Fund instead. (The press briefing where Pat Moynihan and senior DOT officials described the bill and the decisions to reporters is fascinating with regards to why the trust fund and dedicated taxes were dropped.)

In the end, with Nixon having removed the political pain of tax increases/extensions but increased the funding generosity, Congress passed the bill pretty much as he wanted, increasing annual mass transit funding over fivefold in five years’ time.

|

Iterations of the Johnson-Nixon Mass Transit Bill |

|||

| Johnson Bill | Nixon Bill | Enacted Law | |

| Dec. 1968 | Aug. 1969 | Oct. 1970 | |

| Contract Authority | $300 million FY71, rising to $600m in FY74 | $300m 1971, rising to $600m FY74 and $1 billion FY75, with $10 billion/12-year goal stated | $230m FY71, rising to $600m FY74 and $1.24 billion FY75, with $10 billion/12-year goal stated |

| Trust Fund? | Yes – Urban Mass Transportation TF | No – contract authority drawn on General Fund | No – contract authority drawn on General Fund |

| Dedicated Revenues? | Yes – increasing share of existing excise tax on new cars, which is held at 8% | No | No |

Amtrak creation

Here, it mattered less what Nixon and his White House aides thought. What mattered was that Nixon had appointed John Volpe as Secretary. The collapse of the financial viability of U.S. railroads had been a slow-rolling disaster for over a decade by the time of Nixon’s first inaugural. Early on, the senior policy team at DOT and the Federal Railroad Administration (including a lot of career carryovers from the Johnson Administration) began to come up with a portfolio of policy options.

As explained in detail in “Amtrak at 50: The Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970,” by mid-December 1969, Volpe had decided to go with the option to create a private company dubbed “Railpax,” give it some initial federal funding, and have it take up the burden of running a bare-bones network of essential intercity passenger routes. In return for being relieved of the burden of having to provide passenger service, the freight railroads would give locomotives and passenger cars to the new entity.

White House clearance of the proposal was not forthcoming, and the White House Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) and the Bureau of the Budget opposed the draft bill. Even Moynihan wrote that Railpax “is an interesting idea, but the Department of Transportation has not given us nearly enough information to decide if it is a good idea.”

Without clearance from Budget, Volpe could not formally transmit the proposal to Capitol Hill, where Senators were eager to see some kind of Administration proposal. Instead, with CEA, Budget, and others (including Ehrlichman) still adamantly against the proposal, Volpe’s staff gave a copy of the bill unofficially to Senator Winston Prouty (R-VT), who offered it as an amendment in the Senate Commerce Committee’s markup. That amendment failed, and Commerce instead endorsed a bill authorizing open-ended federal operating subsidies to the freight railroads to continue passenger service, which Nixon promised to veto.

With that stalemate, Volpe was able to lobby the Senate in favor of Railpax, which would be a “private, for-profit corporation” instead of a bottomless federal money sinkhole. By May 1970, the Senate was voting for the Railpax bill, 78 to 3, and House later passed the bill with the same overall structure but increased loan guarantees.

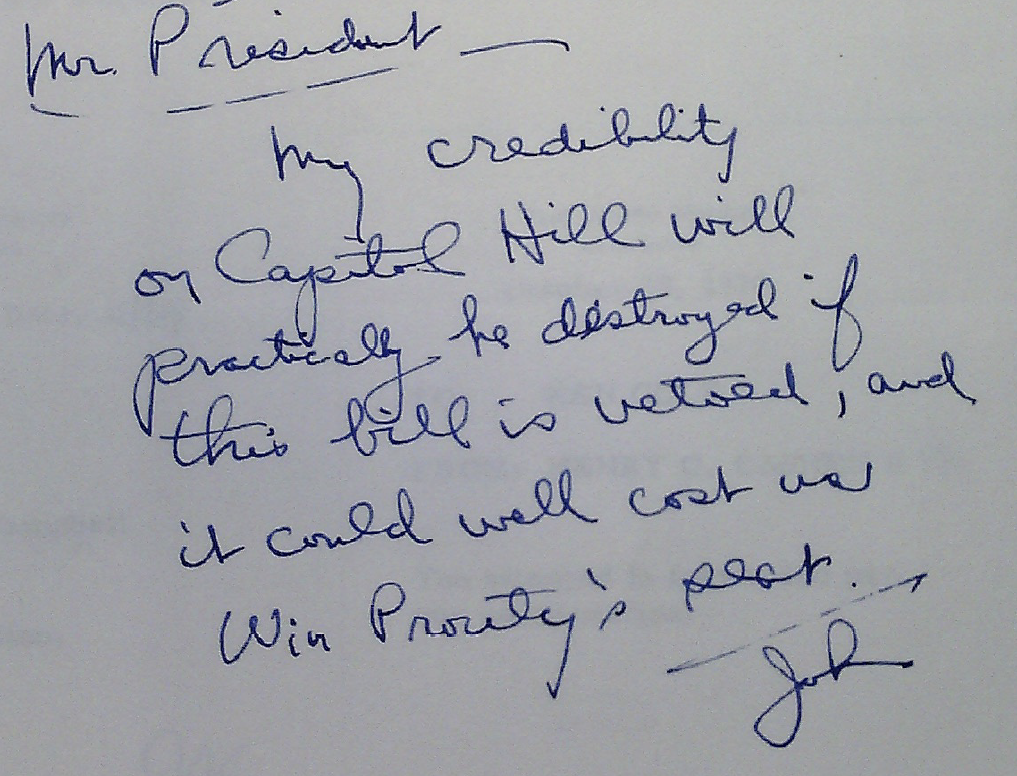

Nixon had never promised to sign the Railpax bill – only that he would certainly veto the operating subsidies bill. The deadline for Nixon to sign or veto the bill was just three days before the 1970 midterm elections. Nixon’s senior advisers (new Budget Director George Shultz and CEA chairman Paul McCracken) both urged a veto. But Volpe pointed out that he had had put his personal reputation on the line, sending Nixon a hand-written note (shown below) pleading “My credibility on Capitol Hill will practically be destroyed if this bill is vetoed, and it could well cost us Win Prouty’s seat.”

Lest there be any doubt about the implicit threat there, Nixon’s business policy advisor Peter Flanigan sent Ehrlichman a memo saying “unless the President is prepared to risk Secretary Volpe’s resignation, I would recommend that he sign the Railpax bill.” Not wanting to risk a last-minute political blowup, Nixon signed the bill (privately, with no signing statement) on October 30, 1970, and Amtrak is with us to this day. (Not really “private,” and definitely not “for profit,” but the trains still run, nonetheless.)

Opening up the Highway Trust Fund

Since 1948, the federal-aid highway program had been reauthorized by Congress on a biennial basis. The 1970 bill passed Congress without a lot of up-front input from the Nixon Administration and was not particularly revolutionary. At a June 10, 1970 hearing, Volpe told the panel that they would wait until an ongoing highway needs study was complete and address the increased need for urban transportation in the 1972 bill.

At the time, the “freeway revolts” were at their zenith, with citizens of big cities around the country fighting against the extensions of Interstates and other proposed highways through their communities. They fought in court and at the ballot box. The federal Highway Trust Fund was becoming a political bogeyman in urban areas – a self-financing entity that would defray 90 percent of the (exorbitant) cost of an urban Interstate spur but could pay nothing towards mass transit service.

The Nixon Administration proposed a radical move in March 1971, with a special message to Congress to propose “revenue sharing” – basically a big block grant to states combining all federal mass transit, highway safety, and airport grant programs, plus all non-Interstate highway programs into one big grant. The sheer audacity of the proposal meant that Congress laughed if off and ignored it, but it got the Administration talking on the record about the need for “balanced transportation” investment in cities.

When 1972 came around, the aforementioned national highway needs study was completed by March, and the number one recommendation was endorsed by the Nixon Administration and proposed to Congress: a Single Urban Fund, combining all non-Interstate highway funding (in urban areas) and all mass transit funding, to be apportioned to states and of which 40 percent would be sub-apportioned directly to metro areas to let them choose what kind of projects they wanted to build with the money, 40 percent to the state government to choose the kind of projects they wanted to build in urban areas in the state, and 20 percent at the Secretary of Transportation ‘s discretion.

The Highway Trust Fund would thus be open to funding for new subways and bus systems, potentially quite a lot (the SUF would be one-third of total Trust Fund spending by the end of the proposed bill).

Pushback within Congress was immediate and severe. As extensively chronicled by Richard Weingroff in “Busting the Trust: Unraveling the Highway Trust Fund 1968-1978,” the highway interests were viscerally opposed to sharing highway user revenues with mass transit, and the transit lobby was leery of the SUF idea because they thought that, if it passed, then they would never get the dedicated Mass Transit Trust Fund that they really wanted.

The House of Representatives developed and passed a 1972 highway authorization bill that did nothing to open up the Trust Fund to mass transit. The Senate version, as it came out of committee, did allow $300 million in Trust Fund dollars to be used in urban areas for highway bus facilities.

Then two Republicans (John Sherman Cooper (KY) and Ed Muskie (ME)) offered an amendment in the full Senate committee to allow local officials to use federal Trust Fund dollars for any type of mass transit project (rail or bus) at their discretion. The amendment passed, 8 to 7, but the following day, Sen. Robert Stafford (R-VT) changed his mind, moved for reconsideration, and the amendment then failed, 7 to 8. (The $300 million Trust Fund set-aside for bus facilities remained in the underlying bill.)

But when the bill went to the Senate floor, Cooper and Muskie offered their amendment again, and this time it passed, 48 to 26. The bill then went to House-Senate conference negotiations, with the House firmly against opening up the Trust Fund to mass transit and the Senate decidedly on board, but still wanting to get a bill completed by the end of the year. White House staff began to wonder if they were better off under a “no-bill scenario,” where Congress failed to pass a biennial highway bill for the first time since 1948. The newly renamed Office of Management and Budget believed that, in the absence of reauthorization, states would start running out of highway money early in 1972, forcing their legislators to support any bill that turned the funding spigots back on.

This is, in fact, what happened. The House-Senate conference committee was unable to produce a final conference report until it was too late (a majority of House members had already left town and, once that was established, the House could take no action other than to adjourn for the year).

Richard Nixon was elected for a second term in a massive landslide in November 1972, finishing 23.2 points ahead of George McGovern (D) in the popular vote and carrying every state except Volpe’s Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. Nixon, having long since lost faith in Volpe, promoted him 4,500 miles away to be Ambassador to Italy and named oil executive Claude Brinegar in his place. His second term assured, and with no likelihood of the 22nd Amendment going away, Nixon no longer needed the progressive agenda of his first term, and prepared to abandon much of it.

(As an indication that Nixon knew his transportation activism had only been a ploy to get re-elected, he flew his protégé Donald Rumsfeld up to Camp David a few weeks after the 1972 election to talk about what job Rumsfeld wanted in the second term. Per Rumsfeld’s’ notes: “He said he felt that I shouldn’t go into the human resource area, HUD or HEW, and not DOT because he was going to be cutting highways and airports and that wouldn’t be helpful to me politically.”)

But first, he had to finish the unfinished business of 1972, and since the White House had made such public commitments, they had to do it on Volpe’s terms. Brinegar toed the line and argued in opening up the Trust Fund to rail and bus transit as Congress moved quickly in 1973 to pass new bills.

The Senate went first, passing a bill that contained the same Cooper-Muskie provision as the prior year (except that Cooper had retired so his spot as cosponsor was taken by Howard Baker Jr. (R-TN)). The House companion bill allowed highway funds to be used from mass transit if General Fund dollars were substituted for Trust Fund dollars.

When the House companion version of the Senate bill reached the House floor, Rep. Glenn Anderson (D-CA) offered the Senate’s Baker-Muskie language, but after extensive debate, it was defeated, 190 yeas to 215 nays. A House-Senate conference committee would decide.

In conference, the advocates of opening the Trust Fund to transit spending were victorious, but not immediately. The local decision provisions would be phased in over three years (FY 1974: House bill, FY 1975: guaranteed $200 million of urban funds for buses; FY 1976: full discretion to use Trust Fund urban system money for rail or bus transit).

In an additional victory for anti-highway cities, the 1973 bill allowed local areas the option to withdraw controversial segments of yet-to-be-built urban Interstates from the map and receive General Fund mass transit funding as a substitute. (This paid for the Washington DC Metrorail system, among others.) And for the first time, some highway formula funding would be “sub-allocated” directly to local metropolitan areas, bypassing the state highway bureau.

Nixon signed the act into law on August 13, and the local option of mass transit choice was later strengthened under President Reagan, when a permanent Mass Transit Account of the Highway Trust Fund was established in 1983.

Conclusions

Richard Milhous Nixon and his Administration:

- Saved intercity passenger rail from extinction;

- Increased mass transit funding, percentage-wise, far more than any other President, ever (including another $3.1 billion slug of transit funding provided in 1973 and not discussed above);

- Established the means of support for robust airport and airways spending that made the next 50 years of growth possible; and

- Got much of the pro-highway bias removed from federal transportation programs by establishing the principle of local choice between highway and transit projects in urban areas, with comparable financial support.

(In addition to that incredible environmental legacy.) Yet, after he was comfortably re-elected, he almost never talked about any of that. His voluminous memoirs only mention mass transit once and the rest not at all. He spent the remainder of his life trying to explain away the Watergate scandal and, never able to do so particularly well, burnishing his (extensive) foreign policy accomplishments.