July 11, 2019

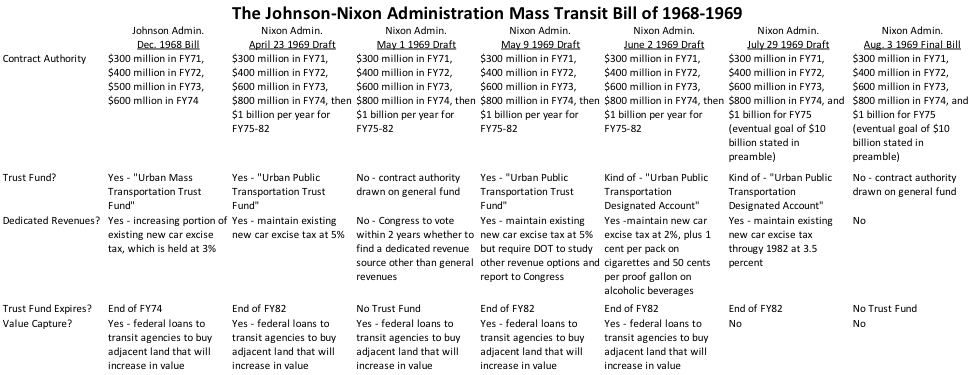

In 1970, in his second year in office, President Richard Nixon signed three landmark transportation bills into law. One of those, the Rail Passenger Service Act (P.L. 91-518) which created Amtrak, was a reactive measure – the increasing bankruptcy rate of private sector railroads, particularly in the Northeast, forced the federal government to take some kind of action, which had not really been well thought out far in advance. But the other two bills – the Airport and Airway Improvement Act of 1970 and the Urban Mass Transportation Assistance Act of 1970 – had been largely developed by the Department of Transportation under Lyndon Johnson’s tenure and then were picked up, dusted off, changed slightly, and then resubmitted to Congress by Richard M. Nixon.

LBJ’s 1968 transit bill. None of Lyndon Johnson’s staff or appointees knew that LBJ was going to withdraw his name from the 1968 presidential contest at the end of his March 31, 1968 televised Vietnam speech. (Ed. Note: The transcript of the Cabinet meeting he held the following day is fascinating mostly because none of them had been clued in beforehand.) But even though the President was not running again, Cabinet agencies kept on developing policy, in the hopes that a Democratic successor would pick up and carry on those policies.

While Richard Nixon defeated Hubert Humphrey on November 5, 1968, the Johnson Administration did not just stop working and walk away. At the Department of Transportation, Secretary Alan Boyd kept putting the finishing touches on an urban mass transportation program.

At the time, while Congress had established a mass transit aid program in 1964, funding was rather limited, and was subject to the annual appropriations process. After the first year, Congress started providing “advance appropriations” to give transit agencies a little budget certainty (the FY 1966 appropriations bill provided the appropriations for FY 1967, and on and on). In 1969, the FY 1970 funding level for the mass transit program was $175 million, which did not seem to be nearly enough to face the transit challenges that major cities would face in the future, and the program faced the need for reauthorization.

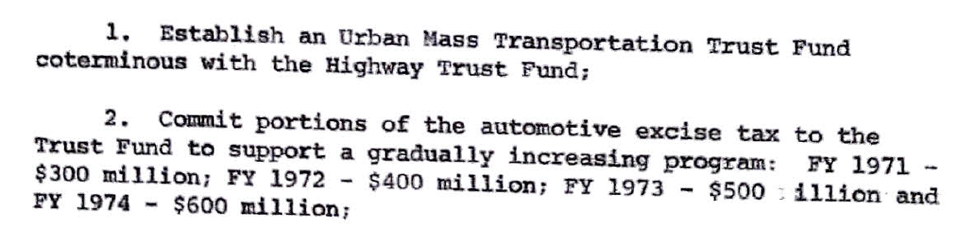

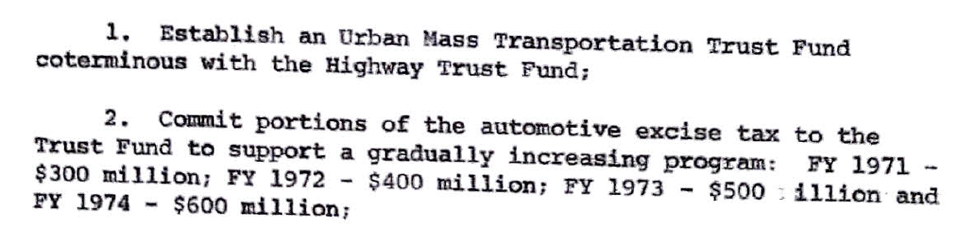

Before the election, on October 17, 1968, Boyd told the Bureau of the Budget that a major mass transit plan would be forthcoming as part of the fiscal 1970 budget request. After the election, on December 13, Boyd send BoB draft legislation that would, among other things:

The massive funding increase would be in the form of contract authority provided directly by the authorization bill, not by annual appropriations.

(Congress had enacted an excise tax on new cars in 1917 as part of the emergency revenue measures to finance the Great War. That car tax had never been allowed to expire. It had been considered for inclusion as part of the highway user tax portfolio to fund the Highway Trust Fund in 1956, but since (a) it was not a use tax and (b) the U.S. auto industry wanted to be able to repeal the tax someday, the tax was not included in the HTF tax package. Instead, in the 1965 excise tax bill, the auto tax was scheduled to drop steadily down from 10 percent to 7 percent in the rest of 1965, 6 percent in 1966, 4 percent in 1967, 2 percent in 1968, and 1 percent in 1969 and all years thereafter, but in 1968, as part of the Vietnam War taxes, Congress extended the 7 percent rate temporarily. Then later in 1968 Congress extended the phase-out so that the tax would drop to 5 percent in 1970, 3 percent in 1971 and then 1 percent in 1972 and thereafter.)

On December 30, 1968, Secretary Boyd sent a memo to White House domestic policy czar Joseph Califano explaining the pros and cons of the bill. Boyd noted that the trust fund/contract authority approach would be similar to the operation of the Highway Trust Fund and would have the advantage of “putting the mass transportation program on the same kind of long-term footing as the highway program; helping to redress the imbalance created by the massive availability and ease with which highway construction funds become available; and relieving local uncertainties about the future availability of federal assistance.”

Boyd also explained other key features of the bill, including the retention of the original 1964 cap on the amount of capital funding that could go to projects in any one state (no more than one-eighth of total capital funding) and two new loan programs – one for advance right-of-way acquisition, and the other for “acquisition of excess land adjacent to the right-of-way which can be expected to increase in value because of the transit development. The requested authority to make loans for excess acquisition of land represents a step towards recoupment by the general public of increased land values that result from public investment. Such a step, while controversial, offers the potential for developing a major new source of revenue for financing local public improvements. Both the community and the Trust Fund would share in profits on such land.”

The memo also notes that the transit authorization was “deliberately limited to four years so that it will expire at the same time as the Highway Trust Fund” which would leave room for the two trust funds to possibly be combined in future legislation. Boyd then noted that the auto industry was likely to bring strong opposition to any plan to extend the auto excise tax and that, strictly speaking, a trust fund with dedicated revenues was not needed to provide long-term funding certainty (at the time, contract authority drawn on the general fund could also be created).

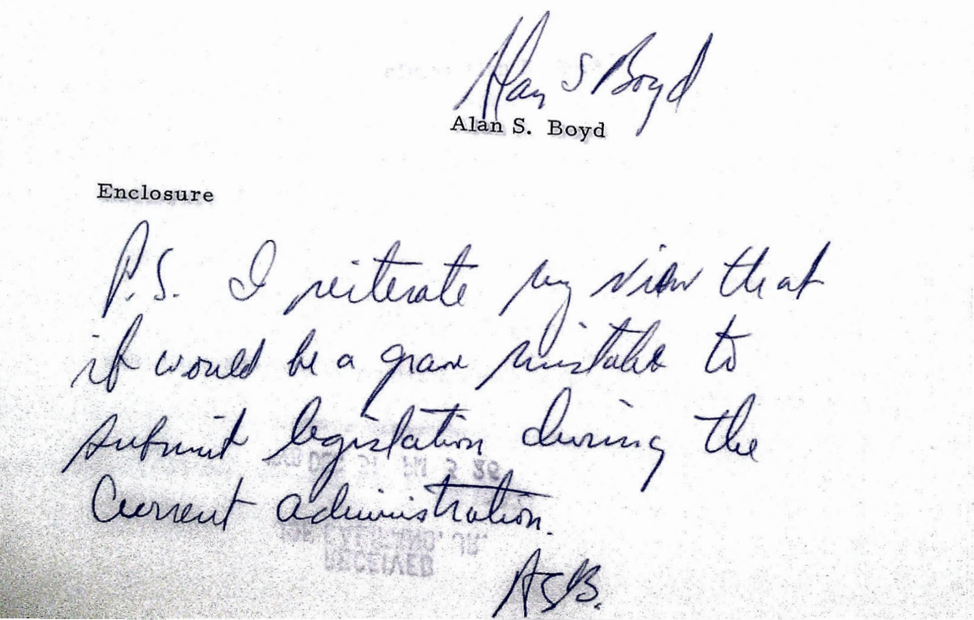

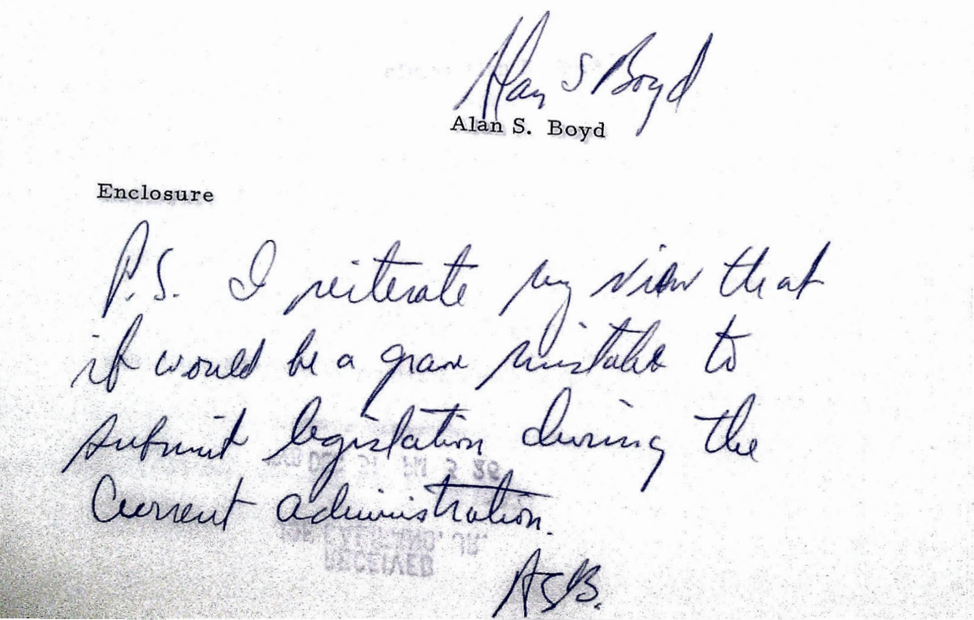

Boyd also hand-wrote on the memo to Califano that he thought it would be a “grave mistake” to submit the transit legislation to Congress under the current Johnson Administration.

![]()

The Johnson Administration did not formally submit the transit bill to Congress, but it did share the bill with friends on Capitol Hill. Accordingly, not long after the new 91st Congress convened, the chairman of the House Banking Committee, Wright Patman (D-TX), introduced the Johnson bill in the House as H.R. 6663 and the chief Senate advocate of mass transit, Harrison Williams (D-NJ), introduced the bill in the Senate as S. 1032.

Nixon takes charge. Richard Milhous Nixon was elected President in 1968 on a Republican Party platform with a stated goal to “explore a trust fund approach to transportation, similar to the fund developed for the Eisenhower interstate highway system, and perhaps in this way speed the development of modern mass transportation systems and additional airports”

The recommendations of his transition team’s transportation task force on January 5, 1968 were strongly pro-transit: “There is no transportation issue on which the Task Force is in greater agreement than the urgency for more adequate funding of the public transportation component of urban transportation systems…Each metropolitan area should be in a position to decide for itself, through a broadly based political process, what the components (auto, bus, rail, parking, etc.) making up its transportation system should be. If comprehensive transportation plans are to be implemented, resources made available must be adequate to support all elements of such plans.” The report specifically endorsed the creation of a Public Transportation Trust Fund.

Nixon named Massachusetts Governor John Volpe to be Secretary of Transportation, and he was confirmed by the Senate with the initial wave of Cabinet officials on January 21, 1969.

Harvard professor of public policy Paul Cherington was a contributor to the transportation transition report and was soon named Assistant Secretary of Transportation for Policy and International Affairs on March 13. (A recent trip to the National Archives to review Cherington’s files forms the basis for the remainder of this article.) And Carlos Villarreal, a senior executive at the transportation planning and engineering firm of Wilbur Smith and Associates, was named to head the Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA) and was confirmed by the Senate on March 17. (Wilbur Smith himself was the longtime chairman of the Eno Transportation Foundation’s Board of Directors.) Volpe also reorganized the job descriptions of the Assistant Secretaries to create an Assistant Secretary for Urban Systems and Environment post, to which he appointed James Braman (who had up until that point been the last Republican mayor of Seattle).

LBJ’s UMTA Administrator, Paul Sitton, remained in office until Villarreal was formally sworn in. On his way out the door, on March 18, Sitton sent Secretary Volpe a memo outlining their transit plan. He was explicit about the long-term goal: “Major strategy in this plan was to move toward a General Transportation Trust Fund, but not actually propose it until mass transit had achieved a better financial footing…inadequacy of Federal resources is not the basic problem; inflexibility in their use is the real difficulty. The balance of political power, not the inadequacy of economic analysis, is the real roadblock to reform…The goal (short of abolishing all trust funds) is a General Transportation Trust Fund with maximum politically possible feasibility in the allocation of Federal aids across transportation modes. Immediate tactical question is whether to propose a GTTF now or to propose a UMTTF now and indicate study and recommendations on GTTF will be ready in time for decisions in 1972 on any new programs when the Highway Trust Fund expires in 1974.”

On April 2, 1969, Secretary Volpe told the Washington Post that he would submit a mass transit trust fund proposal to President Nixon within a month. This naturally caused some all-hands scrambling at DOT, with Volpe telling UMTA Administrator Villarreal the following day to “begin intensive work” on a legislative proposal. Cherington wanted a longer bill (which would have gone against the secret plan to merge the transit and highway trust funds in 1972) and was also not sold on the use of the auto excise tax as the funding mechanism.

On April 4, President Nixon met with Pat Moynihan, his new urban affairs advisor, and other aides at his winter retreat in Key Biscayne, Florida. Moynihan then wrote Volpe to say that Nixon was “most enthusiastic” about a mass transit trust fund plan and “asked that you be given every support in the work you have to do in putting together a feasible proposal.”

Choosing a plan. An internal UMTA task force issued a report on April 15 outlining the issues at stake and giving four policy alternatives, all of which relied on the trust fund/contract authority model:

- Alternative 1 – the Johnson Administration bill (4-year bill, auto excise tax).

- Alternative 2 – a 4-year bill with slightly lower spending levels than the Johnson plan, financed either by the auto excise tax or part of the cigarette tax.

- Alternative 3 – a 10-year bill with higher spending levels (up to $600 million in 1973 and $1 billion per year after that), financed not just by the auto excise tax but also by either some new urban highway user charges or cigarettes after 1973 as well as the profits from the value capture real estate element starting in 1975).

- Alternative 4 – a 15-year plan to merge the transit program with the urban highway program, funded by the auto excise tax and part of the existing HTF tax stream as well as other new taxes and real estate value capture, with the Johnson bill’s transit funding levels for the first four years (as well as $450 million per year for urban highways for four years) but merging the urban mass transit and urban highway programs into a much larger urban block grant program starting in 1975.

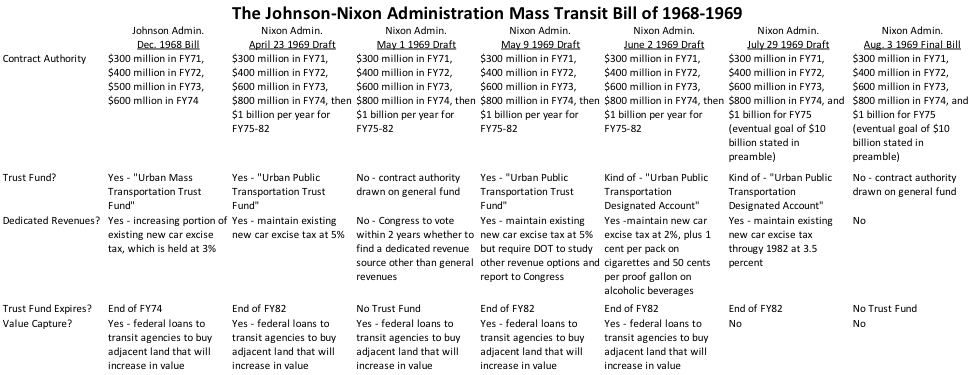

There was a major all-hands meeting at DOT on April 17 to review the task force report, and Alternative 3 was chosen as a starting point but the duration was increased to 12 years (a duration that was probably chosen because the 12th year got the total funding in the bill slightly over the $10 billion threshold). Draft legislation was prepared by April 23 and circulated within DOT. The legislation, along with various internal comments, was presented to Secretary Volpe on April 25. In a summary cover memo, Cherington advocated against locking in reliance on the auto excise tax for 12 years, instead proposing to force Congress to vote on either extending it or finding another revenue source after three years. Legislative liaison Charles Baker (father of the current Governor of Massachusetts) agreed with Cherington and went further, proposing to get rid of contract authority as a tactical measure because of the growing opposition within Congress to “back-door” financing. And Federal Highway Administrator Frank Turner proposed instead to keep the auto excise tax at 5 percent, deposit the money instead in the Highway Trust Fund, and use the money to pay for the highway programs currently financed by general revenues (public lands, beautification, and safety) as well as mass transit.

Volpe vacillates. At the April 25 meeting, Volpe gave up on the idea of a trust fund and dedicated tax receipts. Instead, as a May 1 follow-up memo outlined, the contract authority would be drawn on the general fund, and after two years, Congress would have to vote on whether or not to find a dedicated revenue source, based on a revenue study to be conducted by DOT. (Volpe also decided to rename UMTA the “Urban Public Transportation Administration.”) However, Volpe was later advised that “the cities will in all likelihood oppose any deviation from the trust fund concept” and then reversed himself again. The version of the transit legislation submitted to the White House Bureau of the Budget on May 9, 1969 for internal clearance was the 12-year, $10.1 billion bill with an Urban Public Transportation Trust Fund supported by the auto excise tax (but with the one-year revenue study intact).

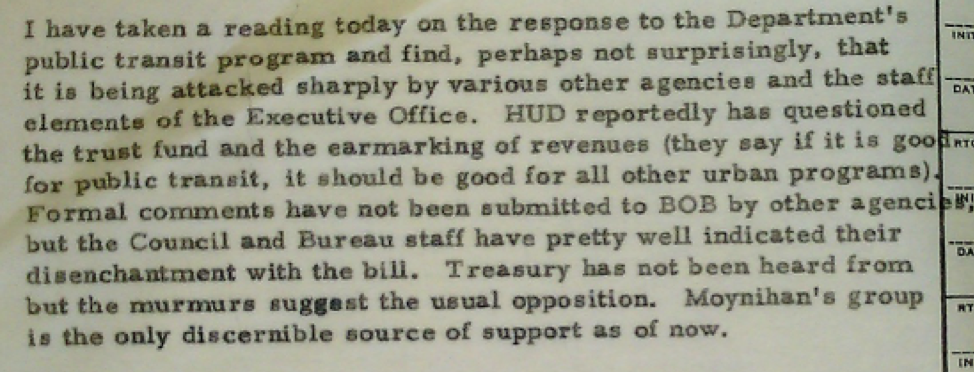

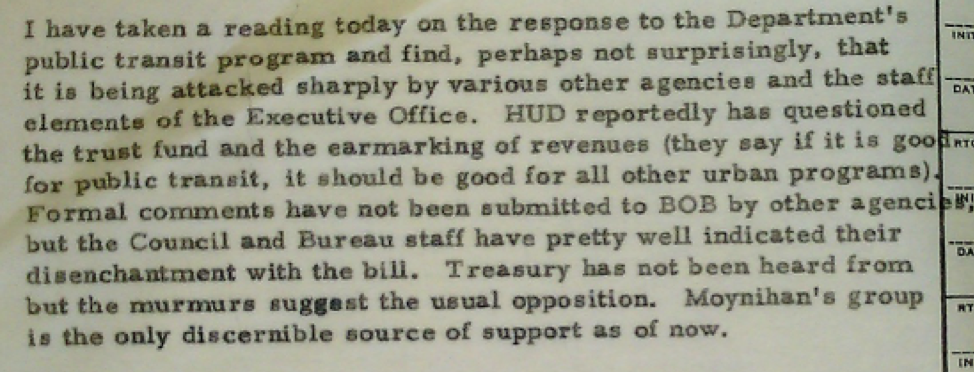

Reaction to the bill by other elements of the Nixon Administration was largely negative, starting with the President’s Council of Economic Advisers and the Bureau of the Budget staff themselves. Cherington’s deputy summed up the situation on May 20:

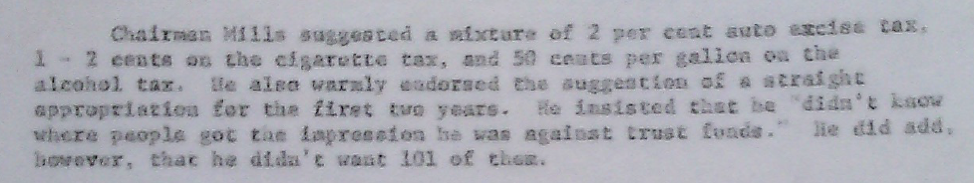

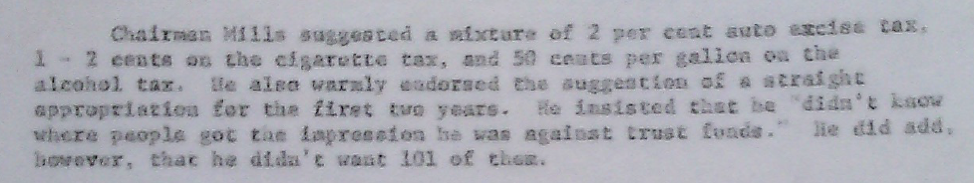

New taxes and new nomenclature. A new approach to the problem came from an unexpected source. On May 27, Volpe met with Wilbur Mills (D-AR), the powerful longtime chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. A file memo the following day from Congressional liaison (and future Senator) Bob Bennett states that:

Accordingly, DOT submitted a revised transit bill to the Budget Bureau on June 3 with the automobile-tobacco-booze tax blend suggested by Chairman Mills. The rest of the bill was the same, except that the taxes were to be deposited in an “Urban Public Transportation Designated Account” – not a “trust fund.” (One of the CEA/BOB standard objections to new trust funds was that people confuse them with real-world trust funds which have fiduciary benefit standards and thus create a lot of public expectations that are not actually required by federal law.)

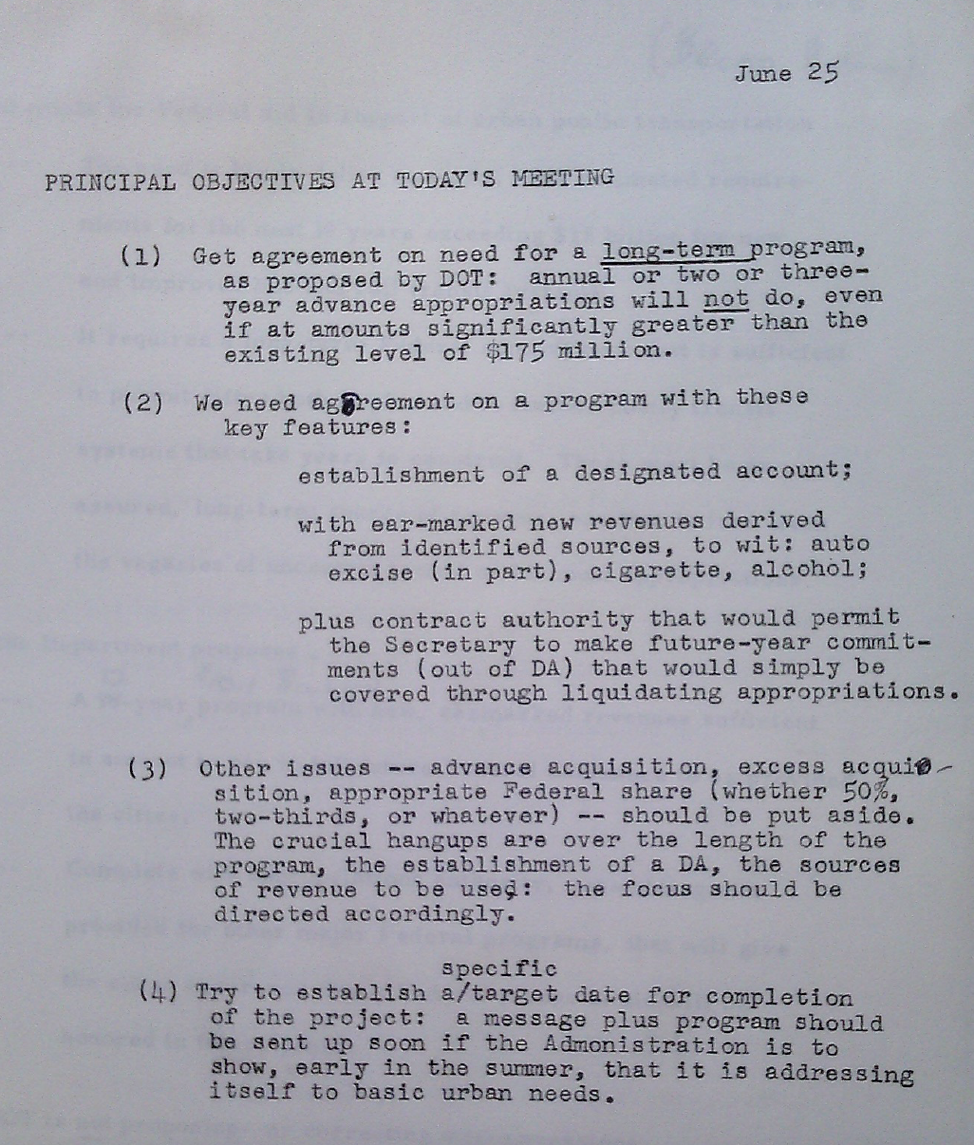

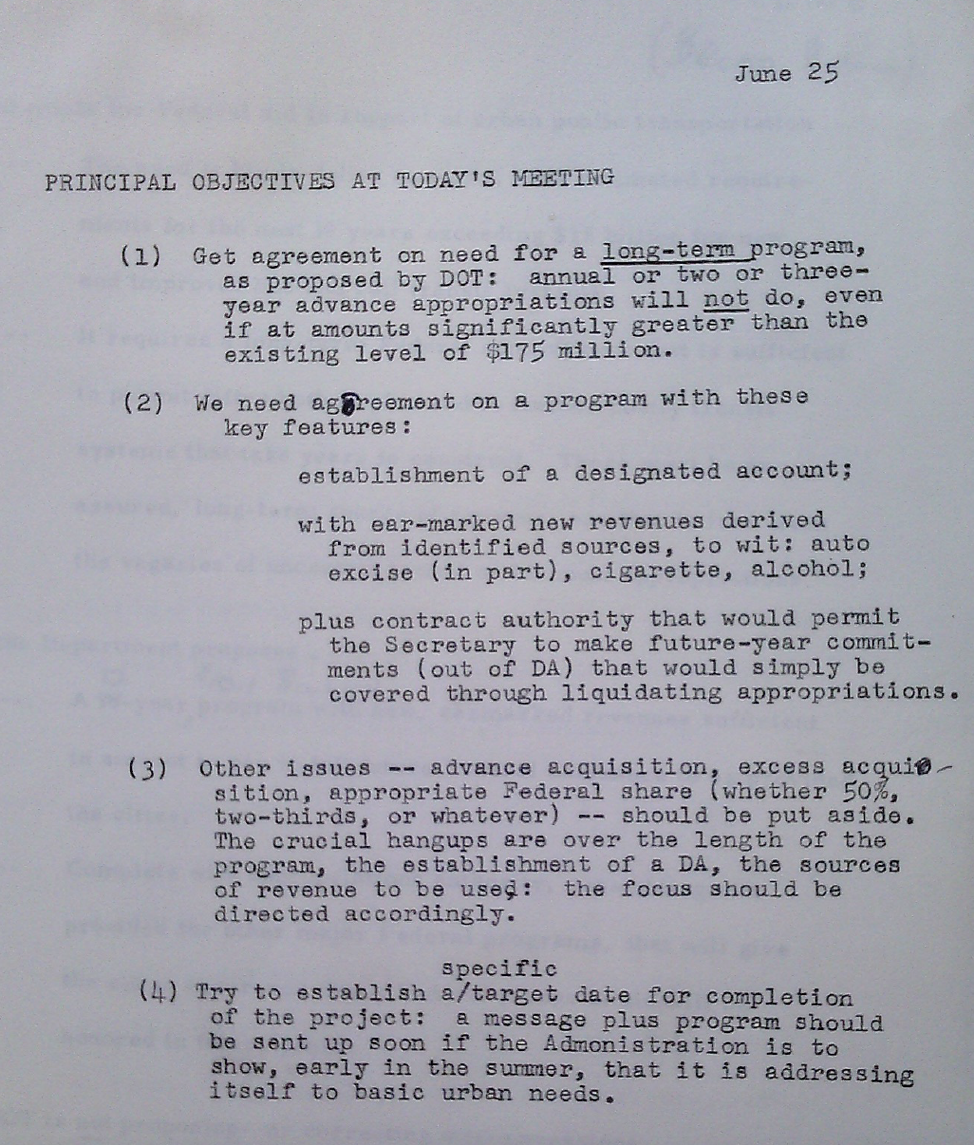

The CEA continued to oppose the bill, not being fooled by the “designated account” nomenclature and also opposing the revenue blend because they weren’t user taxes. The Treasury Department and BoB also opposed the trust fund/designated account concept. A high-level “principals” meeting between Volpe, top White House economic aide Arthur Burns, Budget Director Mayo, and Pat Moynihan was held on June 25. Volpe’s staff laid out the goals of the meeting:

At that meeting, the trust fund concept was again rejected, as was contract authority. A June 30 follow-up memo from UMTA staff indicated that “The program will be supported by general fund revenues with an authorization for appropriations of $3.1 billion for the Fiscal Years 1971-1975. (Two-year advance appropriations would be sought and these appropriations would be available until used. Appropriations requested in FY 1970 would be $300 million for FY 1971 and $400 million for FY 1972.) The two-year lead would be maintained by requesting an additional year of advance appropriations in each succeeding year, e.g., $600 million would be requested in 1971 for Fiscal Year 1973 and $800 million would be requested in 1972 for Fiscal Year 1974. (In Fiscal Year 1972, a proposal would be made to extend the authorizations for an additional five years.)” However, the memo also said that “We understand the door is open to further discussion [of funding and revenue structure] if DOT policy officials wish to pursue the matter further.”

Cabinet-level decisions. A high-level internal DOT meeting on the funding issues was held on July 2 in advance of a White House Cabinet Council meeting scheduled for July 7. A summary of that meeting indicates that the options were narrowed down to three alternatives: (1) “designated account” with dedicated excise tax revenues and contract authority; (2) general fund contract authority, or (3) simple authorization for general fund appropriations.

Assistant Secretary Braman strongly favored alternative 1, because “A great deal of support has been painstakingly built up around this approach. This support will disappear if an alternative is proposed, but the support can be brought to bear once the bill is submitted by the Executive Branch…” UMTA Administrator Villarreal also supported alternative 1 because “he belives that it is the ideal vehicle for gaining essential local support and confidence in the program” but was willing to support alternative 2 as a fallback. Assistant Secretary Cherington “believes that a designated account is unsaleable without earmarked revenues that approximate user charges. The automotive excise tax does not meet this test (although it would be better than sumptuary taxes) but a license fee on urban drivers or vehicles would be closer.” He thought alternative 2 was better but that alternative 3 would be the most likely to pass Congress.

Cherington followed up with a memo to Volpe on July 10 urging a real user tax – “an annual Federal excise tax levied on privately-owned motor vehicles registered in urban areas. Such a tax is far superior to any of the other ideas so far advanced for fueling an UPT trust fund.” He estimated that an $11 per year tax would be enough to fund the full program and that the administrative aspects of the tax would be “manageable.” (Using CPI-U inflation, $11 in July 1969 would have been about $75 today.)

Some clarity was reached in a July 7 Cabinet subcommittee meeting between Volpe, HUD Secretary George Romney, and Commerce Secretary Maurice Stans. The formal report of that meeting proposed a bill with a formal goal of $10 billion in spending over 12 years but that only the first five years of contract authority, totaling $3.1 billion, be provided in the bill itself. But there was no unanimity on the source of financing, with Romney and Stans (along with CEA and BOB) supporting general fund contract authority and Volpe holding out for a designated account.

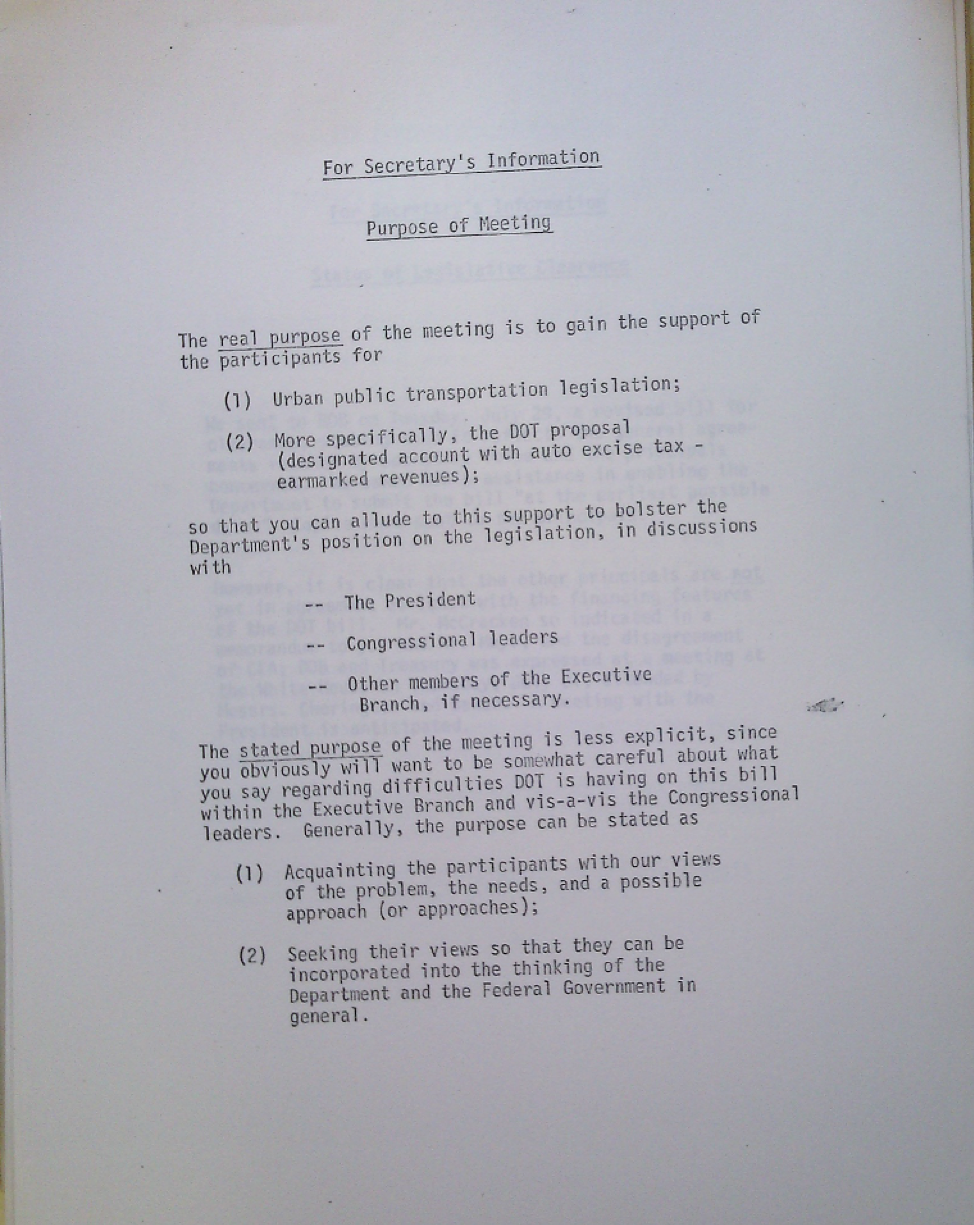

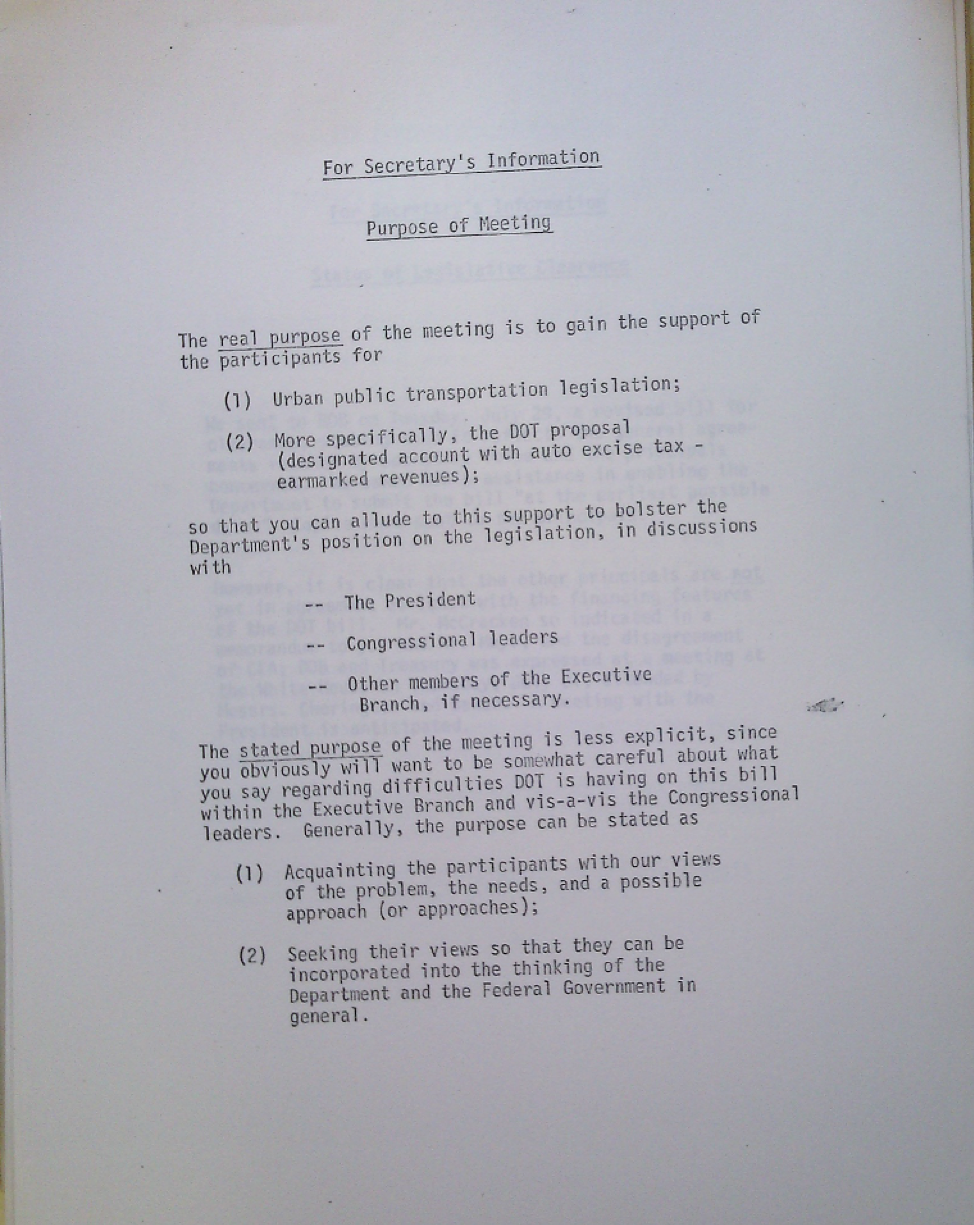

The final verdict. Volpe sent the Budget Bureau yet another bill on July 29, this one reflecting the decisions made at the Cabinet Council (which included the rejection of the value capture provision that would have made loans to buy transit-adjacent property), with $3.1 billion in contract authority over five years, but again with the designated account funded by the auto excise tax, in hopes that Volpe could build enough support from transit interests to get the White House to agree. Volpe invited transit stakeholders to DOT for a July 31 briefing (later postponed to August 4). A memo given to Volpe reveals, quite candidly, that the real purpose of the meeting was a bit different than the stated purpose:

But any stakeholder pressure was too little, too late. On August 5, the decision was made to abandon the “designated account” and dedicated excise tax approach and instead just propose general fund contract authority. The final bill was transmitted to the Budget Bureau for clearance on that day and was formally transmitted to Congress on August 7 in a special presidential message. The bill was also explained by Under Secretary of Transportation James Beggs, UMTA Administrator Villarreal, and Pat Moynihan at a White House press conference that same day (transcript, which is fascinating, here).

Coming soon: the story of the Johnson-Nixon airport and airways bill.