Fifty years ago today, President Nixon signed into law the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970 (Public Law 91-518), relieving the nation’s railroads of the requirement that they continue passenger service and creating a new National Railroad Passenger Corporation to carry on that service starting in May 1971. That corporation would later name itself Amtrak.

Background

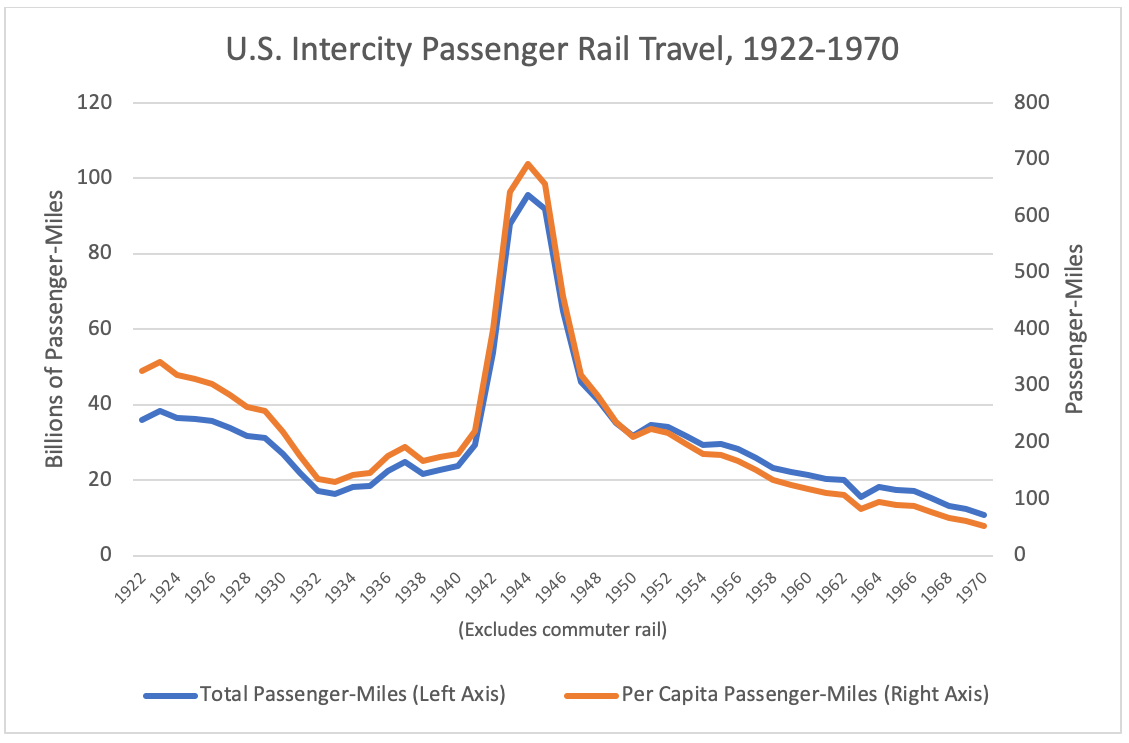

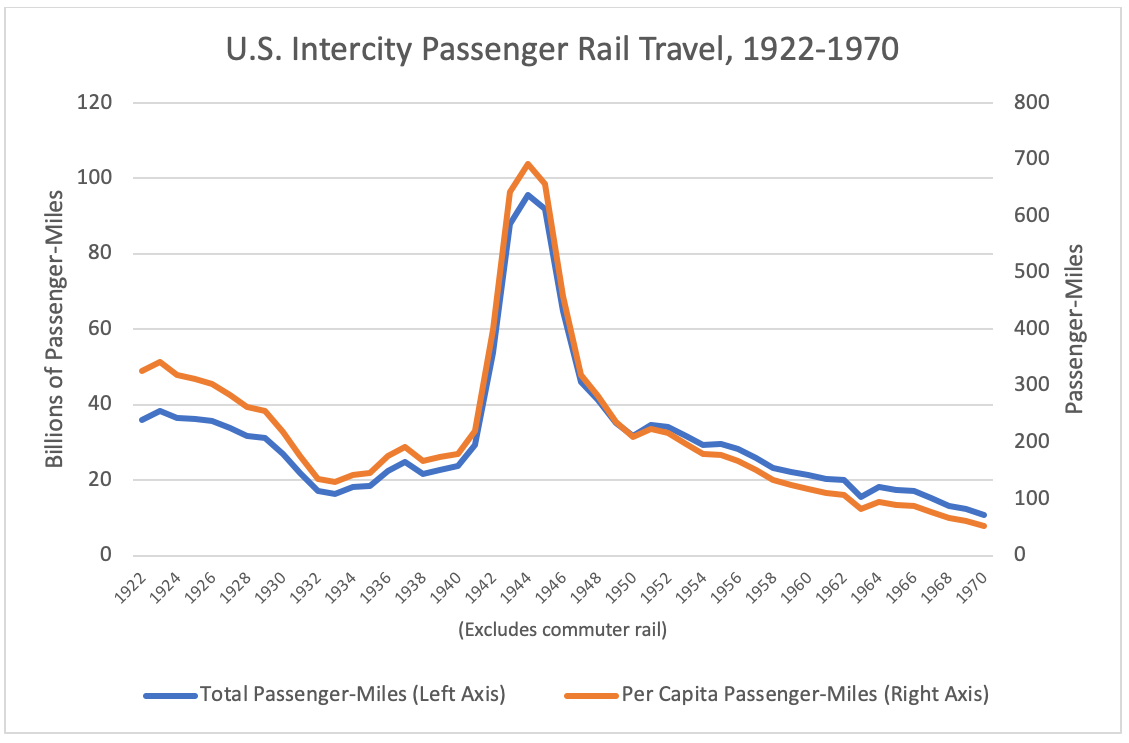

By the 1960s, the nation’s railroads had been in poor economic health for decades. Intercity passenger rail demand started to decline after World War I as competition from the automobile for short and middle-distance routes grew. Things stabilized during the Great Depression, due to cheaper fares and also because of increased effort by the freight railroads (more comfortable cars, the beginning of dieselization, etc.), and New Deal relief also paid to electrify some of the Northeast Corridor, increasing service there.

When World War II broke out, federal rationing of gasoline and tires and the government takeover of most civil aviation forced passengers onto the rails and interrupted this trend. But after the war, the decline continued, with traffic back down to prewar levels by the mid-1950s. At the same time, the booming airline industry was eating away at the demand for long-distance travel. In the eleven-year period from 1951 to 1961, per capita intercity rail passenger-miles were cut in half. And from 1961 to 1970, per capita passenger-miles were cut in half once again. In 1970, the average American only rode 53 miles on intercity railroads (excluding commuter rail), down from a 1951 level of 224 miles per capita and a World War II peak of 691 miles per capita.

Every year, fewer passengers wanted to ride, but the railroads were prohibited by law from abandoning unprofitable passenger service without permission from either a state public service commission or the federal Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). After a lot of debate on railroad policy within the Eisenhower Administration, the Transportation Act of 1958 was enacted, which created a new “section 13a” procedure allowing the ICC to take jurisdiction away from state commissions and make it easier for railroads to abandon passenger service. Some unprofitable passenger lines were abandoned, but the ICC refused many other requests.

A few months after the 1958 Act was signed, the ICC released a pessimistic report on the future of passenger rail service (the “Hosmer report”). The study found that the nation’s railroads had lost over $7 billion providing passenger service over the 1946-1957 period, and that the “passenger deficit” had been $723 million in 1957. The Hosmer report concluded:

The passenger deficit is not something which can be conjured away by statistical legerdemain. It is real and serious. Unless a good start toward reducing it can be promptly made the future welfare of the railroads will be gravely endangered. In fact there is here a disturbing overtone due to an implication that the passenger deficit may be a symptom of more deep-seated infirmities for which some remedy must be found if the railroads are to survive.[1]

As part of the political machinations to get the 1958 law through the Senate, that chamber commissioned a detailed staff study (through the Senate Commerce Committee) of the national transportation system. That report, issued in July 1961 (National Transportation Policy a.k.a. the “Doyle Report”), recommended that “a very thorough economic market analysis should be made” of passenger rail operating costs from the ground up, and “If the results of such a study indicate profitable operations based on conservative traffic and financial forecasts, a national passenger service corporation should be formed which would have complete control of marketing and producing the service.”[2]

The report even included a detailed outline of how such a corporation could be structured, but cautioned, “Since the original premise is not to initiate a national railroad passenger service corporation unless conservative forecasts indicate a very good possibility of profit it would be most likely that the corporation could become a profitable venture and, therefore, a good investment.”[3]

The decline of passenger rail nevertheless continued, and every few months brought more bad news, whether through the quarterly financial reporting of the railroads or through other means. The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad declared bankruptcy in 1961. A year later, the Boston Terminal Corporation filed for bankruptcy because the city of Boston was trying to seize South Station for unpaid taxes. (Railroads had many gripes about federal policy, but the fact that they had to pay to build and maintain, and pay property taxes on, their own stations while federal and state government paid to build and maintain airports, using tax dollars paid by railroads, was toward the top of their list.)

In 1967, the Central Railroad of New Jersey declared bankruptcy. Later in 1967 came a major kick in the teeth from Uncle Sam – the Post Office canceled its remaining contracts with railroads for the transport of mail. Randal O’Toole, in Romance of the Rails, wrote that “most railroads moved mail and passengers in the same trains, thus earning twice the revenue for the same basic cost. Mail revenues actually exceeded passenger revenues on many trains, so cancellation of the mail contracts led to more passenger trains being discontinued.”[4]

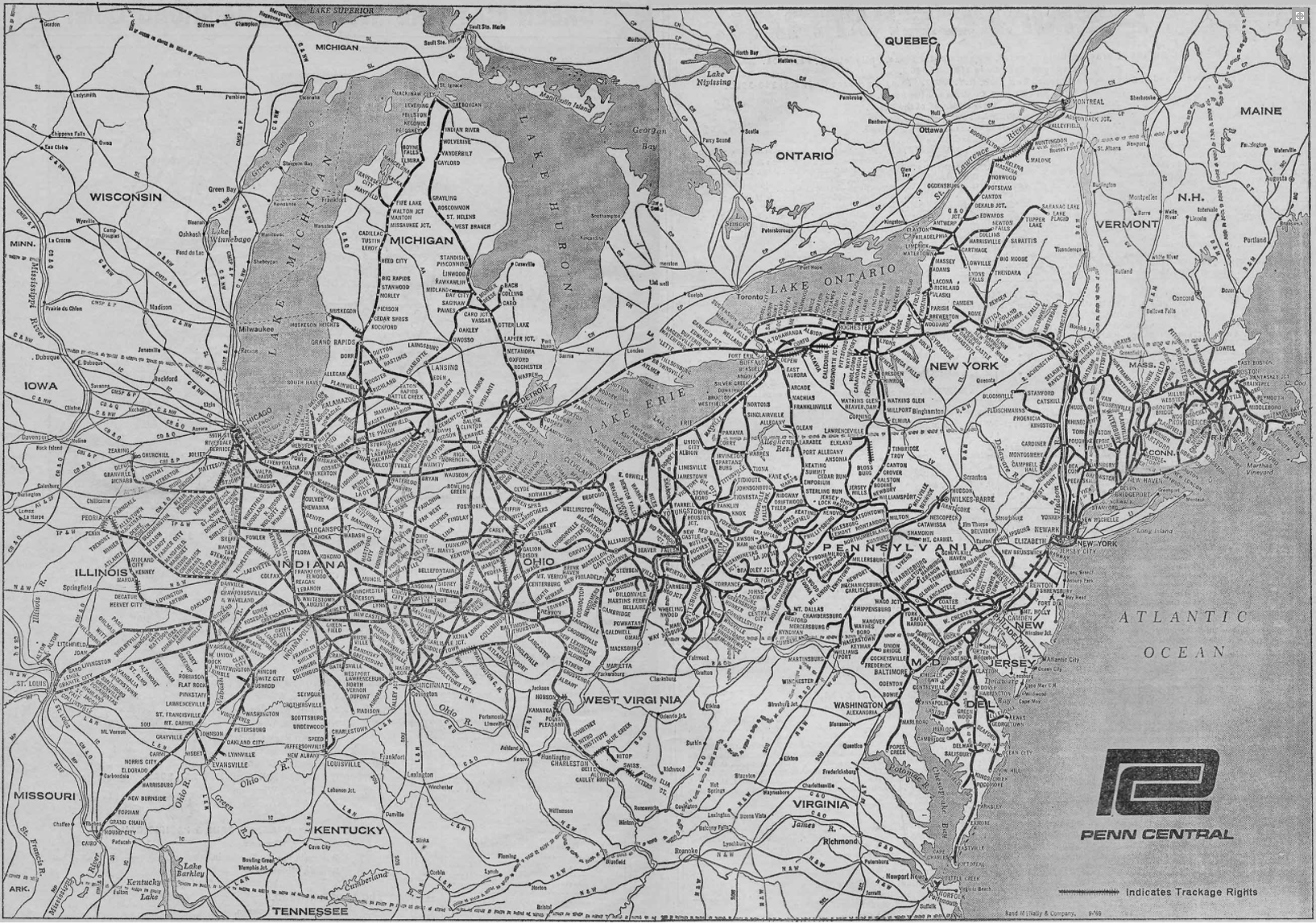

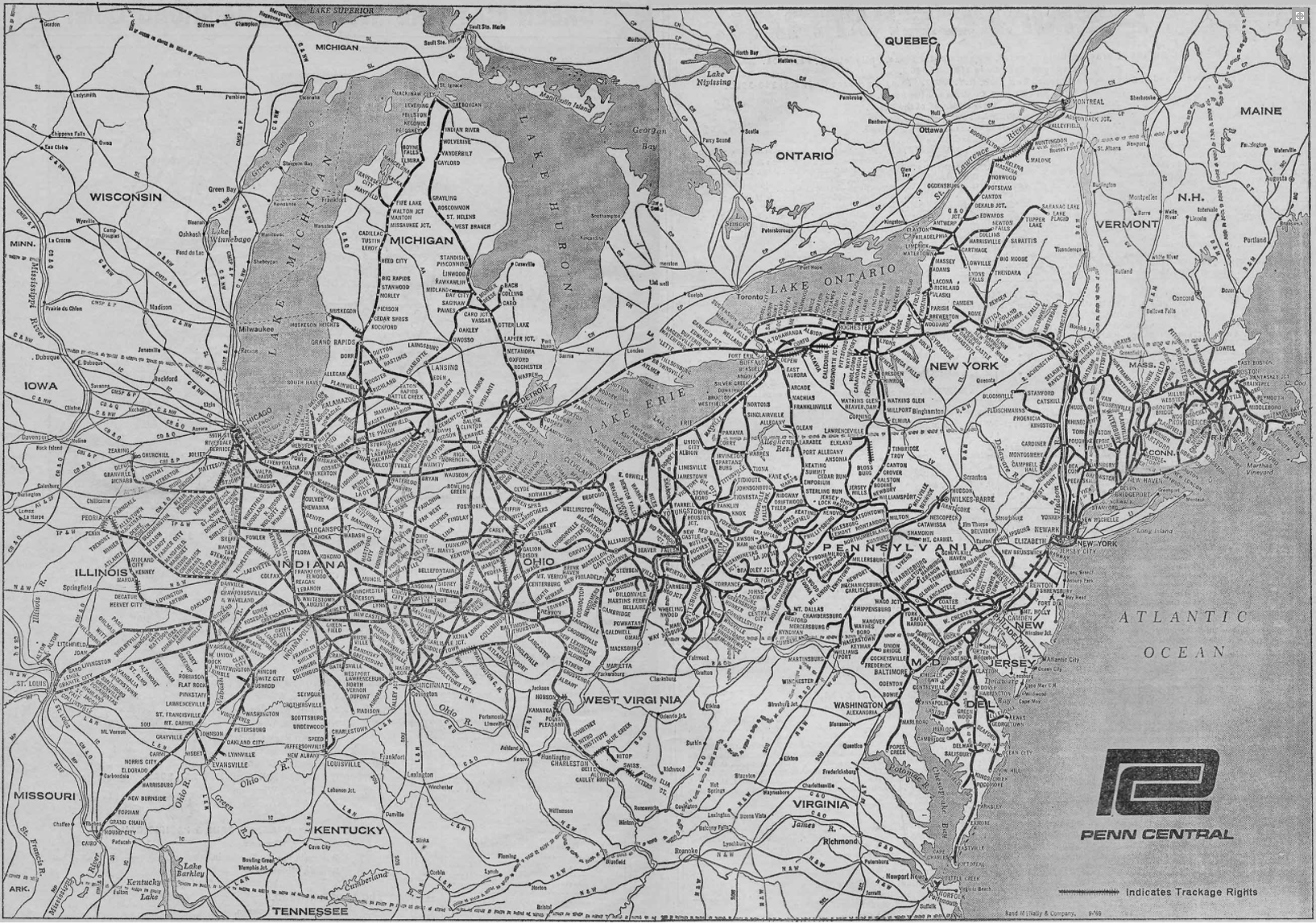

Meanwhile, the two biggest railroads east of the Mississippi, the Pennsylvania and the New York Central, decided to fight their economic malaise by merging into a mammoth “Penn Central” that came into being in February 1968 as the sixth-largest corporation in the United States. It would go down in history as one of the most misguided corporate mergers of all time.

In exchange for its approval of the merger, the ICC forced the new Penn Central to take over the bankrupt New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad. The result was a colossus that dominated the Northeast, Ohio and Indiana.

In July 1969, the ICC produced a follow-up report to the Hosmer report which looked at the detailed finances of the passenger operations of eight railroads and concluded that, if all eight had been able to cancel all their passenger train service, they would have saved a collective $118 million in 1968. The report found “For every $1.00 in revenues that these carriers, as a group, would have lost by not operating any intercity passenger service in 1968, they would have avoided $1.83 in expenses.”[5]

Railroads had other problems beside their passenger train deficit, to be sure, but the continued difficulty railroads had in abandoning the money-losing passenger service made the passenger train problem the one that Congress had to address. The Senate Commerce Committee held hearings in September 1969, where subcommittee chairman Vance Hartke (D-IN) led off by saying “Congress should not let the passenger train disappear from the scene by default…There seems to be a market, there seems to be an interest, the question is what should be done and what can be done by the Congress.”[6]

Several bills had been introduced in the Senate, which the committee examined. Hartke had first introduced his own bill (S. 2750, 91st Congress) authorizing unlimited federal operating subsidies of railroad operation of passenger routes that they had tried to abandon but been denied ICC permission and requiring the Department of Transportation to provide the railroads with new rolling stock, if need be. But Millard Tydings (D-MD) and a group of other Senators including Claiborne Pell (D-RI) had their own bill (S. 2939, 91st Congress), the “Intercity Rail Passenger Service Act of 1969.” It called for DOT to purchase all passenger rolling stock from the railroads, maintain and upgrade the rolling stock as necessary, and then lease the rolling stock back to the railroads, thus relieving them of most of their capital costs for maintaining passenger service.

DOT proposes “Railpax”

As far back as 1968 (under the Johnson Administration), the policy staff at DOT had been looking at potential options for the provision of passenger rail service in what is now called the Northeast Corridor. A report authored by Richard Barber (Deputy Assistant Secretary for Policy) in late 1968 (but not released until 1970) looked at several different options for a new NEC rail service provider, including a federal agency, a federal corporation, an interstate compact, a new private corporation, and a new quasi public-private corporation.[7]

Throughout 1969 at DOT, policy staff from the Office of the Secretary and from the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) were looking at options. Jim McClellan, who was then on the FRA policy team, later wrote, “Everyone, including the White House, understood that passenger trains made sense in the Northeast. Some believed that there were other corridors that might work. Almost no one had any belief that long-haul passenger trains were needed, or, indeed, would ever be needed. But again, our overriding concern was to find a solution that removed the passenger burden from the back of the Penn Central and the other freight railroads. The collapse of passenger railroading was acceptable; the collapse of freight railroading was not.”[8]

As to what kind of entity would provide the passenger service, McClellan wrote “The DOT/FRA team debated structure at some length, but in the end focused on a single national entity that would contract for passenger services with the railroads…We felt that having a myriad of rail carriers, some still doing a good job but most not, created a huge image problem. If the passenger train was to have a fighting chance, it needed a pro-passenger management with nationwide responsibility and a nationwide identity.”[9] Robert Gallamore, who was in the DOT policy office at the time, says that the name for the entity, “Railpax,” came from Assistant Secretary for Policy Paul Cherington, as a portmanteau of “railroad” and “pax,” an abbreviation for “passenger” in common use in the aviation sector (where Cherington had previously worked as an analyst.)[10]

At the September Senate hearings, the Federal Railroad Administrator, Reginald Whitman, testified that DOT was working on several different proposals. One was for a new 50-50 matching grant program to states and localities to take over their own intercity passenger rail operations. Another was for federal grants to railroads for rolling stock equipment and initial roadbed and safety improvements, if the route was profitable or else subsidized by state and local governments.

And a third option was the creation of “a private corporation to provide rail passenger service in selected high-density routes throughout the Nation for at least a 3-year period. The corporation, which we have called ‘Railpax’ in our discussions, would have a board of directors composed of stockholder representatives and Presidential appointees. The plan envisions ownership of stock by railroads and the public.”[11]

Whitman said that railroads would pay Railpax a fee equal to 150 percent of their annual avoidable passenger losses, which would mean that “no Federal funds are required.” (About that payment—McClellan wrote that “In essence, the same government that had forced [railroads] through regulation to stay in the business was now going to make them pay to leave. (When the Mafia does a shakedown like that, someone goes to jail.)”)[12]

If Railpax then found a route to be unprofitable and wished to discontinue it, Whitman said “States or municipalities could contract with Railpax for partial or full support of the service.”[13]

He then added that DOT was about three months away from completing its analysis and recommending a final course of action, which Congress took to mean that they would submit a proposal by the end of 1969. Whitman reiterated the options at House hearings in November 1969.

Upon taking office, Nixon had appointed former Massachusetts governor John Volpe as Secretary of Transportation. Volpe had been Federal Highway Administrator under President Eisenhower and, as governor of the Bay State, he had almost been picked by Nixon has his 1968 running mate before Nixon reversed course at the last minute and chose Maryland governor Spiro Agnew instead.[14]

By mid-December 1969, Volpe had officially decided to go with the Railpax idea. A draft bill and explanatory material were sent by DOT to the Bureau of the Budget (BoB) for the interagency “clearance” process on December 23, 1969. The draft bill would have created a private company (not “an agency or establishment of the United States Government”), answerable to a 13-member board (seven Presidential appointees, three from railroad stockholders, and three from non-railroad stockholders), with Class A stock to be held by railroads and Class B stock to be “sold at a price and in a manner to encourage the widest distribution to the American public.”

Although the draft bill did not say so explicitly, the section-by-section analysis made it clear that the bill authorized “the creation of a corporation for profit.” McClellan later wrote “Most (including a number of us on the planning team) were dubious of the ‘for profit’ claim, but the reality was that neither the White House nor the more conservative members of Congress were going to sign off on an entity that was set up to be a perpetual ward of the state. And the pro-passenger crowd did not object; many of them had argued that passenger trains could be profitable if they were just run right. The ‘for profit’ mandate haunts Amtrak to this day.”[15]

Under the draft bill, the Secretary of Transportation would designate a Basic System of routes that the corporation would operate. Starting in January 1974, the corporation could start cutting unprofitable routes unless state, regional or local authorities agreed to cover future operating losses. The draft bill authorized $40 million in startup appropriations from Congress and another $60 million in federal loan guarantees to the corporation.

White House resists Railpax

Assistant Secretary of Transportation Paul Cherington went to the White House on January 12, 1970, to make the case for Railpax to the staff. The bill and the presentation did not go over well—BoB and the Council of Economic Advisers did not like the bill, and other Cabinet agencies had some concerns. On January 14, after Transportation Secretary Volpe had briefly talked to President Nixon on the phone, Volpe told Budget Director Bob Mayo that Budget was the only federal department or agency that objected to the Railpax bill, and Mayo responded that, if that were true and if President Nixon decided to support the bill, he might be able to find the $40 million by shorting funding for the supersonic transport plane. But the next day, Mayo found out about the opposition from CEA and other agencies, and then told Volpe that, in light of the opposition, his offer to find the money was withdrawn.[16]

By Monday, January 18, news of the proposal had leaked, and a description of the Railpax proposal was in the newspapers the following day, as if it were already Administration policy (the New York Times headline was “Nixon Drafts Bill for Body to Run Passenger Trains”). This prompted immediate pushback from the White House – BoB made clear that it was opposed, and Nixon’s press secretary Ron Ziegler said Railpax was only one of a number of proposals under consideration. Per the New York Times, this response “confused and dismayed some Department of Transportation officials. Sources in the agency said that, as recently as Friday afternoon, they had been led to believe that the White House and the Bureau of the Budget had endorsed the plan.”[17]

(This would not be the last time that DOT and the White House had different opinions on Railpax.)

On January 23, White House domestic policy czar John Ehrlichman sent President Nixon a pair of short memos. One was an outline of the railroad situation, which concluded that Congress might pass the Hartke bill (limitless federal subsidies for passenger train operating losses) “without the Administration having given a definitive alternative to Congress which could have been supported by the Republicans…”[18] The second memo outlined for possible options – submit Railpax on behalf of the Administration; have a Senate Republican introduce Railpax on his own; propose Railpax without any federal dollars (except for the loan guarantee); or just amend section 13 of the Interstate Commerce Act and allow railroads to end all their passenger service. (Ehrlichman noted that “It has always been considered political suicide to talk about discontinuing trains”.)[19]

On January 28, Nixon’s one-man domestic policy brain trust, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, warned Ehrlichman in a memo that Railpax “is an interesting idea, but the Department of Transportation has not given us nearly enough information to decide if it is a good idea.”[20] He recommended that the plan be sent back to DOT with instructions to answer two questions:

At around this time (late January or early February 1970), Secretary Volpe sent President Nixon an (undated) memo to try and clear things up. In it, Volpe defended Railpax, then wrote that “There has been a regrettable amount of discussion of this problem and related alternatives in the papers already. I say regrettable because a number of statements have been attributed to the Department of Transportation which, if made, were both premature and unwise. Nonetheless, we are faced with the need to take a position and relay that position to Congress.”[21]

Ehrlichman told Nixon on February 4 not to worry about Volpe’s memo, writing that “We have indicated to DoT that the staff work is not complete and have requested additional work by them on this matter…There is no reason for you to spend time with the Secretary’s memoranda or the back-up material at this time.”[22]

DOT sent Under Secretary Jim Beggs and Deputy Under Secretary Charlie Baker to the White House on February 12 to make another pitch for Railpax. A Ehrlichman staffer later wrote “There is a consensus of opinion that this briefing could have been conducted in a more professional manner,” Ehrlichman requested that DOT prepare a report for possible submission to the President on the pros and cons of various options for dealing with the passenger train problem.[23]

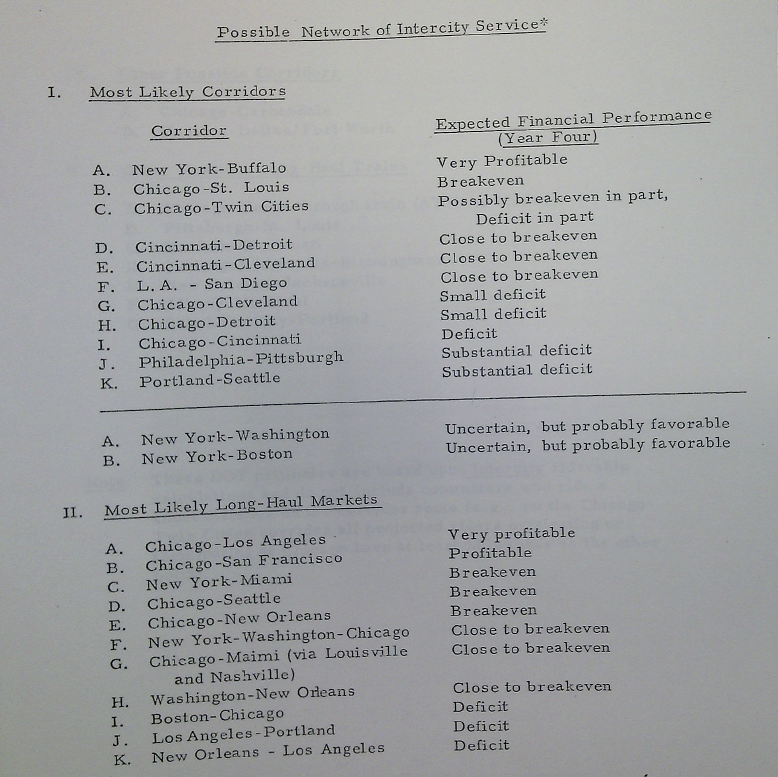

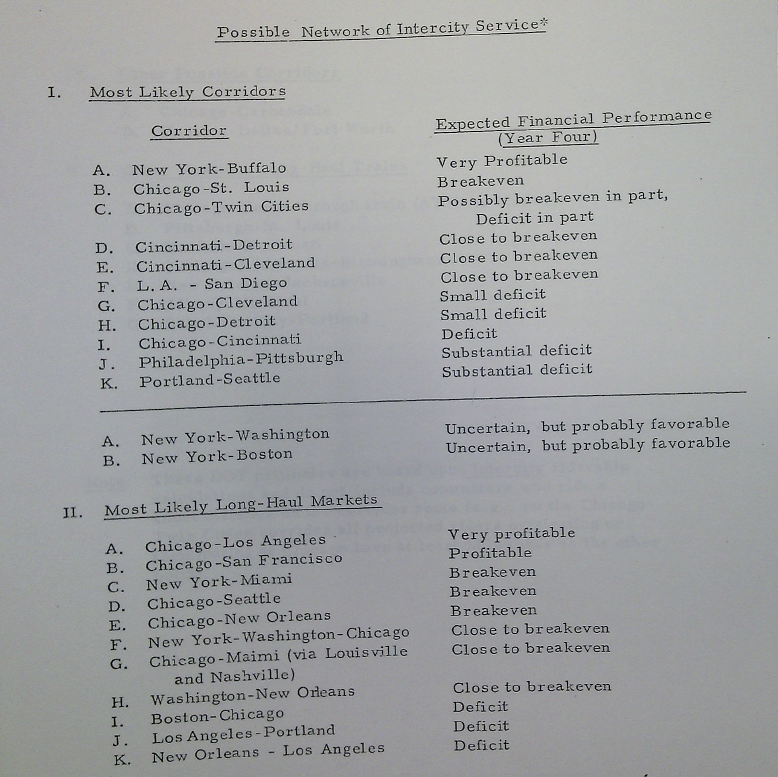

Beggs at DOT sent Ehrlichman the additional material on February 18, writing that “the analysis we conducted over the last several months lead us to the conclusion that this proposition, while undoubtedly less than perfect, is in our judgment the best course of action in the real world.” The analysis paper looked at six options: direct subsidies, complete free market, status quo, a moratorium on discontinuances accompanied by a study, a series of regional rail compacts, and Railpax. The analysis also included a list of potential corridors operated by the Railpax corporation, along with their expected financial performance in the fourth year of the company. (The Chicago-Los Angeles corridor was estimated to be “Very Profitable” in the fourth year.)[24]

Budget responded with a very negative memo to Ehrlichman on February 23, stating that “DOT makes four basic arguments in favor of RAILPAX, which we believe are not supported by their own analysis.” BoB said that the very need to save rail passenger service was not proved, that DOT’s estimates of Railpax profitability were overly optimistic, that Railpax would inevitably see the Federal role expand over time, and that the impact of Railpax on other modes had not been analyzed. OMB recommended that railroads be allowed to discontinue all passenger service – or, failing that, that a Railpax completely free of all federal subsidies be created.[25]

Ehrlichman agreed, telling President Nixon in a March 2 memo that Volpe “feels under some pressure from the Senate to come up with an alternative. However, his staff work has been quite mediocre and incomplete…it would appear that the Federal government should not get involved in this. If the Senate acts on some kind of 100% subsidy proposal, we will probably recommend that you veto it.”[26]

Volpe finally got his long-awaited meeting with Nixon (and Ehrlichman) on March 5, 1970 at 3:30 in the afternoon, but Ehrlichman had prepared Nixon with a memo urging that Nixon not make any commitment to Volpe at that time. This is where the paper trail in the White House files at the Nixon Library stops for many months. What happened in this meeting?

CBS News’s young White House correspondent, Dan Rather, later wrote that Volpe’s personal Railpax pitch to Nixon (possibly in this meeting) “evoked romantic images of America’s past when passenger trains gave people the opportunity to travel about and see their wonderful country. Despite his disappointment over not being picked as Nixon’s running mate in 1958, Volpe must have been paying attention the night of the acceptance speech in Miami Beach when the nominee conjured up a vision of himself as a lonely boy in Yorba Linda lying in bed at night listening to train whistles and dreaming of faraway places.”[27]

After the March 5 meeting, the Railpax proposal was never formally transmitted to Congress.

Formally.

Railpax goes over the transom to the Senate

As all this was happening at the White House, Senate Commerce chairman Warren Magnuson (D-WA) and subcommittee chairman Hartke were losing patience. The Boston and Maine Railroad had declared bankruptcy on March 12, raising the prospect of more bankruptcies to come. The Commerce Committee began holding discreet executive sessions to discuss passenger train legislation (so discreet that they were not listed in the Daily Digest of the Congressional Record, which is problematic from a research standpoint).

Hartke combined elements of several proposals into one new bill—the operating subsidies for private railroad passenger losses from his own bill, the DOT rolling stock pool from the Tydings bill (which would save the railroads all future capital costs), and the direction that the Secretary of Transportation designate a minimum basic national passenger route system.

Steve Ditmeyer, who was one of the FRA staffers on this project at the time, now recalls that “Secretary Volpe received a phone call from Senator Winston Prouty (R-VT) [Hartke’s minority counterpart on the subcommittee] who said the Senate [Commerce Committee] was going to vote on the passenger train subsidy bill the next day and asked if the Secretary could get him a copy of the Department’s draft Rail Passenger Service Act.”[28]

The authorization to leak the bill could have come from the very top – months later, in his memo to Nixon to implore him to sign the bill into law, Volpe wrote that “On the eve of reporting out by the Senate Commerce Committee of Senator Harkin’s $435 million subsidy bill, I intervened with your agreement.”[29]

Regardless of who exactly gave the Railpax bill to Prouty, by sometime in the first week of April 1970, Prouty’s staff had made a few tweaks to DOT’s legislation and offered it in committee as a substitute for the Hartke subsidy bill. Prouty’s proposal failed, and the Commerce Committee voted, 12 to 4, to approve Hartke’s bill.[30]

Instead, Commerce filed its report on the revised Hartke bill (renumbered as S. 3706, 91st Congress) on April 9 (S. Rept. 91-765). Prouty filed dissenting views starting on page 76 of the report and included the text of his version of the Railpax bill at the end of his views.

(We may have Prouty to blame for the fact that Amtrak’s legal name sounds weird. The original DOT proposal would have created a National Railroad Passenger Service Corporation. But the version that Prouty offered in committee and printed in the report dropped the word “Service” for some reason and would have created a National Railroad Passenger Corporation, and that version of the name survived to enactment and since to this day. Whereas anyone with a reasonable facility for the English language has to admit that “National Railroad Passenger Service Corporation” would sound much better than the actual name.)[31]

Although Railpax had failed in committee, getting a bill to the Senate floor involved both party leaders and the general acquiescence of the entire Senate. The White House did not like Railpax, but they disliked the open-ended federal operating subsidies of the Hartke bill more, and Senate Republicans, backed by a firm presidential veto threat, refused to let the Hartke bill move forward.

Talks continued behind the scenes, and as they did, the virtues of Railpax – a “private” company that was “for profit” and would not need any federal subsidies after 1973 – became more and more apparent. By April 28, Under Secretary of Transportation Jim Beggs was ready to announce to the press that the Nixon Administration and Senate leaders had agreed to support a modified Railpax plan. The press reported Beggs saying that “the White House had relaxed its objections to the plan for the Government’s initial investment in the new passenger train corporation, while at the same time the Senate Commerce Committee had withdrawn its insistence on a still more costly system of operating subsidies.”[32]

The Commerce Committee printed the new bill (as Committee Print No. 7) and quickly circulated it to stakeholders to get letters of support. On April 30, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-MT) got the unanimous consent of the Senate to make S. 3706 the pending business, and the next day, on behalf of the bipartisan Commerce Committee leadership, Mansfield introduced the modified Railpax bill as a substitute amendment (Sen. Amdt. #608) for the entire bill (see text starting on page 13845 here). The text of the bill said Railpax was to be “a for profit corporation.” A one-time appropriation of $40 million in startup costs was authorized (along with no more than $60 million in federal loan guarantees), plus an additional $75 million in direct federal loans and loan guarantees to railroads to enable them to buy into Railpax.

Senate debate began on May 5. One major alternative was offered, on May —a complete substitute for the bill, proposed by Sens. Claiborne Pell and Ted Kennedy (D-MA) (S. Amdt. #618, text on p. 14269 here). The Pell-Kennedy bill would have replaced one Railpax with many—one private, non-profit corporation per urban rail corridor. For long-distance routes, the bill was a bit vague (“The Secretary is authorized to contract with railroads and the corporations for the provision of passenger service within the national basic passenger system for rail passenger service outside of the urban corridors passenger system if the Secretary finds that such service is required to meet seasonal passenger demand, to meet passenger transportation demand for which no alternative mode of transportation exists, or to meet other requirements in the national interest.”)

Pell told the Senate that urban corridors under 500 miles were where the traffic was, and where the need was, not long-distance trains. He warned “If investors are not willing to put their money in present rail corporations providing long-distance passenger service, they are no more likely to put their money into a rail corporation providing long-distance passenger service. No matter where it is put, uneconomic long-distance passenger service does not produce dividends for investors.”[33]

Hartke responded that the Pell-Kennedy bill, with its 18 corridor corporations, was unwieldy and unworkable, and said “I have been assured by Secretary Volpe that the situation with respect to long-haul service may not be as bleak as commonly assumed…The proposal thus would eliminate service that is now well patronized, deprive the public of a good transport alternative, and axe thousands of rail jobs.”[34]

After debate, “well realizing that I do not have the majority support of this body,” Pell withdrew his amendment. The Senate then went on to pass S. 3706, with a half-dozen minor amendments, by a vote of 78 to 3.[35]

(The text of S. 3706 as passed by the Senate is here starting on p. 14287.)

The House debates and decides

In the House, Rep. Robert Tiernan (D-RI) introduced the Pell-Kennedy bill as H.R. 17849 (91st Congress) on May 27. The House Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee held hearings in the first week of June on both the Senate-passed bill and the Pell-Kennedy-Tierney bill.

Secretary Volpe testified on June 2: “With sufficient capitalization, a new, quasi-public corporation, whose only purpose is to maintain and improve rail passenger service over a more economically sensible system, has a good chance of becoming a sound and successful enterprise…I do not wish to leave the committee with the impression that there are no risks in the course of action proposed by S. 3706. The rejuvenation of railroad passenger service will require a great deal of effort, dedication, and imagination. These traits have never been lacking in American enterprise, and S. 3706 provides a framework within which they can be exercised. On behalf of the administration, I strongly urge early and favorable consideration of S. 3706 by this committee and the Congress.”[36]

(The committee asked the Bureau of the Budget for its opinion, in writing, and Budget responded with a tepid, one-sentence statement: “The Bureau of the Budget recommends that your Committee give favorable consideration to S. 3706 rather than H.R. 17428.”)[37]

The president of the Association of American Railroads testified that they were not opposed to the Senate-passed bill, but with a few amendments (a hard effective date for serviced discontinuance, another alternate method of calculating each participating railroad’s financial contribution to Railpax, and some technical amendments), it could have their strong support.

The Congress of Railway Unions expressed its wholehearted support for S. 3706, but labor thought Railpax was underfunded and wanted it more than doubled. A representative of the Railway Labor Executives Association said that the federal financial aid authorized by the bill fell “far short of the amount necessary to inaugurate a financially sound and efficient national rail passenger system. Moreover, even the increased funds and guarantees proposed by us remain far below those which are available under the Urban Mass Transportation Act and the High Speed Ground Transportation Act for the development and preservation of commuter and intercity corridor passenger traffic.”[38]

The National Association of Rail Passengers endorsed the Senate bill and most of the amendments sought by AAR, as well as supporting the extra federal financial support sought by the unions.

Nothing happened in the House immediately after the hearings, but the passenger train situation jumped back into the spotlight on June 21, when the Penn Central declared bankruptcy—the largest corporate bankruptcy in American history (it would not be surpassed until Enron in 2001). A subsequent Securities and Exchange Commission report found that the culprit was losses on railroad operations, not the Penn Central’s other businesses:

|

Profit/Loss on Rail Operations, Penn Central and Predecessor Companies (Million $$)

|

| CY |

CY |

CY |

CY |

Jan.-Mar. |

| 1966 |

1967 |

1968 |

1969 |

1970 |

| +2.6 |

-85.7 |

-142.4 |

-193.2 |

-101.6 |

| Source: SEC staff report, August 1972 |

Penn Central management blamed the bankruptcy on passenger service losses (though the subsequent SEC investigation shared blame with the freight operations as well), putting a great public mandate on Congress to Do Something.

In July, the House subcommittee began holding closed-door executive sessions on the bill, and by August 11, the subcommittee had approved an amended version of S. 3706, accepting some of the amendments suggested by AAR and the unions. Congress then took its summer recess before the full Commerce Committee could act.

On September 23, the full House committee ordered a “clean bill” reported and sent to the Ways and Means Committee informally, because one of AAR’s requested amendments involved allowing railroads to deduct their financial contributions to Railpax from their taxes as a business expense. Ways and Means agreed, and on October 7, Interstate and Foreign Commerce formally substituted the text of the amended S. 3706 for H.R. 17849 and then ordered H.R. 17849, as amended, reported to the House. (Because of the tax law change, the bill had to have a House bill number, per the Constitution.) The report was filed later that day (H. Rept. 91-1580).

The bill reported to the House expanded the loan guarantees for Railpax and the private railroads significantly beyond what the White House had reluctantly supported in the Senate bill.

|

Financial Aid Authorized in the Railpax Bill (Million $$)

|

|

Aid to Railpax

|

To Railroads |

|

|

Direct |

Loan |

Loan |

|

|

Appropriation |

Guarantees |

Guarantees |

TOTAL |

| Senate-passed bill |

40 |

60 |

75 |

175 |

| Labor union proposal |

100 |

100 |

200 |

400 |

| House (final) bill |

40 |

100 |

200 |

340 |

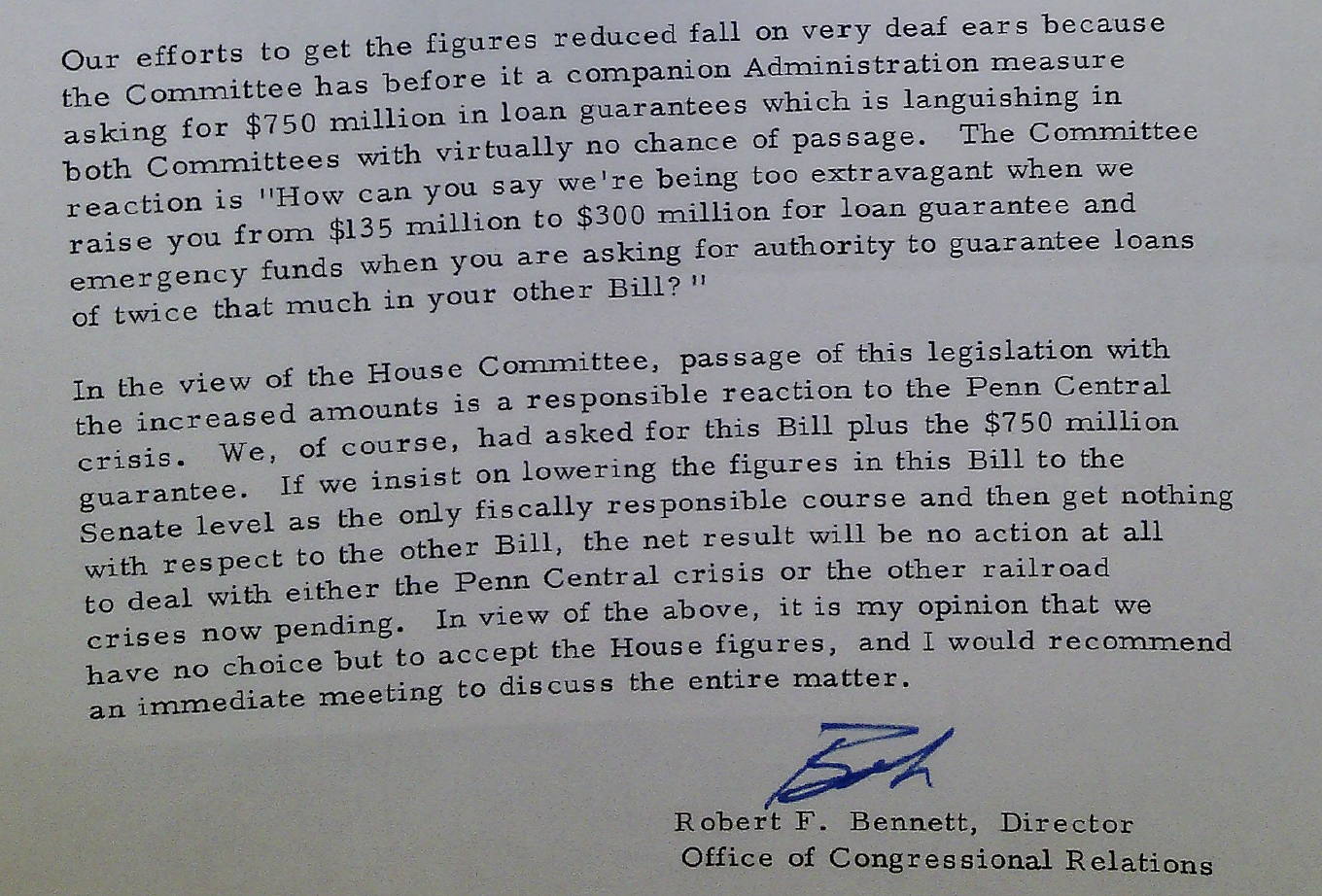

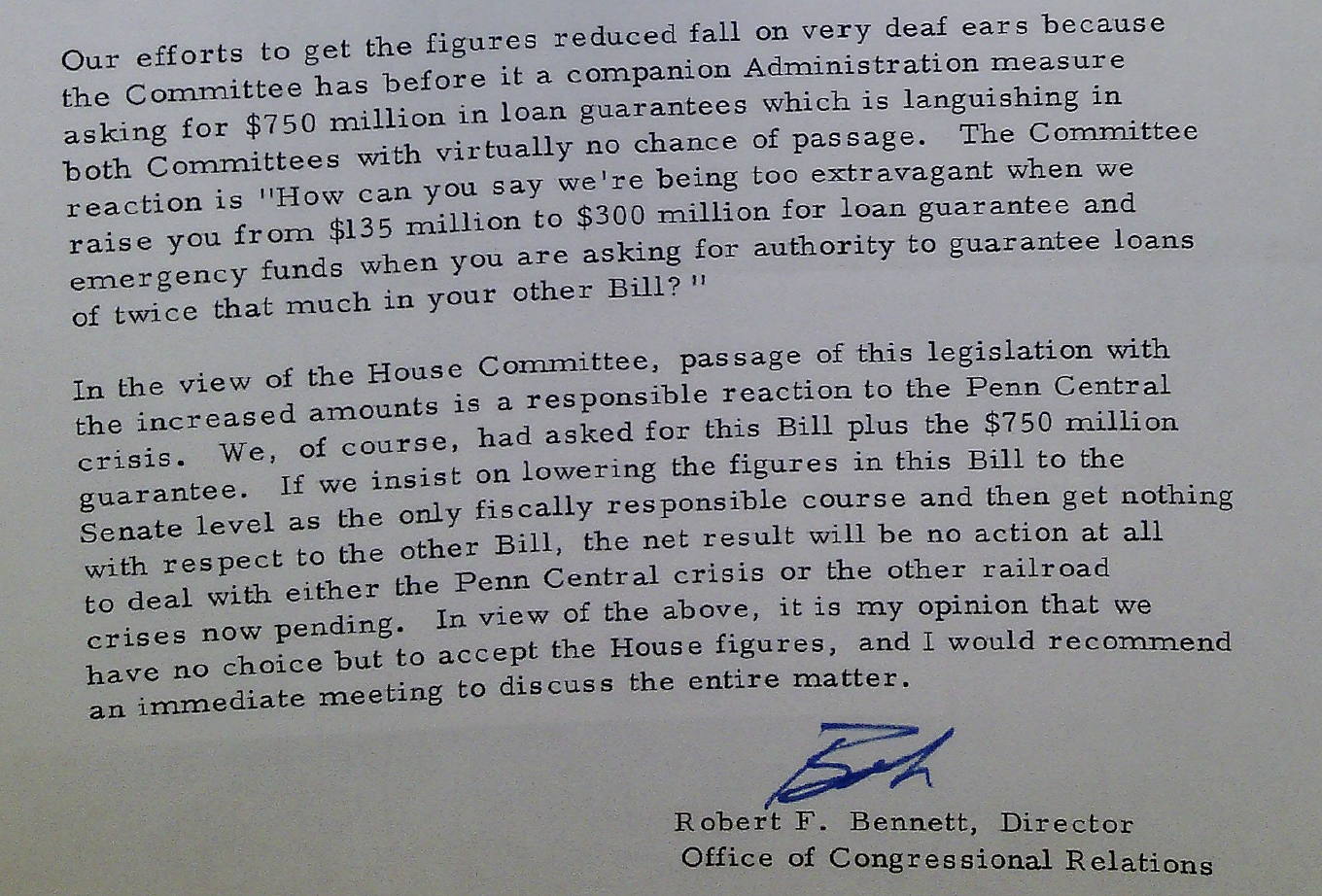

On October 9, DOT Congressional liaison (and future U.S. Senator) Bob Bennett wrote to the White House to notify them that the Railpax bill was on schedule for a House vote the following week and that “The Senate Committee is anxious to get this Bill passed before the [pre-election] recess and is prepared to accept the House bill without a conference if the House can pass it early enough on Wednesday to permit Senate action Wednesday evening.”[39]

Bennett noted that the higher loan guarantee levels in the House bill were problematic, but suggested that the White House would just have to accept them, because of the Penn Central crisis:

White House staff debated whether or not to issue a veto threat because of the higher funding levels or have a Republican House member offer a floor amendment reducing the funding, but decided against it. Importantly, the day the House was considering the bill, John Ehrlichman talked to Secretary Volpe and they agreed that, if Congress wound up providing more appropriations and loan guarantees than had been authorized in the Senate-passed bill, the President would simply impound the money (refuse to spend it or lend it). (This was 1970, and Congress would not outlaw impoundments until 1974.)[40]

The House Rules Committee granted a special rule allowing H.R. 17849 to come to the floor on October 13, and the bill came up later that day. The debate, which spread into the following day, was a bit anticlimactic. Even though the bill was brought up under an open rule, allowing any germane amendments, the only amendment offered was a technical one changing a date.

Commerce chairman Harley Staggers (D-WV) assured the House that “We know that in starting off they are going to have some trouble, but I expect that after a very few years it will be a prosperous organization, because we have begun to develop high-speed trains, better railroad cars, with more commodious service that people will use, as has been exemplified by the Metroliner that runs between Washington and New York now. The people are using these trains because they are acceptable, they are clean, and they afford rapid transportation from the heart of one city to the heart of another. I believe that with this as an example, this corporation will be able to move forward, and make a go of it…This will be private, as I said, a private corporation to be run for profit.”[41]

The House passed the bill by voice vote on October 14, 1970. Later that day, as the Senate prepared to leave for its election recess, the Senate took up the House-passed bill and passed it by unanimous consent, with almost no debate. (Commerce chairman Magnuson submitted a statement for the Record outlining what he said were the two small differences between the original Senate-passed bill and the House bill, and Gordon Allott (R-CO) made sure that Win Prouty, who was up for re-election, got his due credit as the sponsor of Railpax.[42]

Secretary Volpe issued a statement congratulating Congress on passing the bill: “The resounding margin by which this bill was passed – by a voice vote in the House – reflects, I believe, the importance Americans attach to continuing and improving intercity rail passenger service for fast, convenient and comfortable travel between urban areas as a matter of public convenience and necessity.”[43] Both chambers then adjourned for a month-long recess, during which the Railpax bill would be enrolled and sent to President Nixon.

There was, however, the not-so-insignificant detail as to whether or not the President would sign the bill.

The White House veto debate

The initial assumption within the White House was that the President would sign the bill into law. Nixon had a trip to Vermont to campaign for Win Prouty scheduled for October 17, and his advisers debated whether or not to have Nixon announce his intent to sign the bill there, alongside Prouty. But that wound up not happening, and afterwards, John Ehrlichman began to have, in the words of an anonymous White House aide on October 21, “serious reservations about the bill. He has had many calls and discussions with Railway people who do not like portions of the bill…whether or not the President will sign the bill is ‘up in the air’ at this time, according to JDE.”[44]

Congress formally transmitted the enrolled copy of H.R. 17849 to the White House on October 21, which started the constitutional 10-day clock (excluding Sundays) for the President to sign or veto the bill, lest it become law on its own. The last day for presidential action was Monday, November 2 (the day before the midterm elections). Because Congress had taken a one-month recess, Nixon had the option of an unreviewable “pocket veto” if he wanted to kill the bill.

Ehrlichman ordered Nixon’s all-purpose economic and business advisor, Peter Flanigan, to come up with a pros-and-cons memo on the bill. That memo was ready by October 27, and Flanigan took issue with DOT’s financial assumptions: “DoT predicts that after a $40 million deficit in the first year, the corporation will decrease its deficit to $9 million in the third year and make a profit in the fourth and following years. The DoT projections are based on the somewhat speculative assumption that improved service will gradually attract increasing traffic. I have been given a more pessimistic estimate, checked with some industry sources, that operating deficits could amount to $50 to $75 million annually.”[45]

After listing several pros and cons, Flanigan said it came down to the fact that Volpe had gone out on a limb in vocal support of the bill before Congress: “If this bill were being now presented to us as a departmental proposal, I would oppose it on economic grounds…Now, however, the bill comes to us for signature or veto having received strong and continuing Administration support through the statements of Secretary Volpe. I do not believe that it is sound administrative practice or politically credible for the Administration, in the absence of overwhelming new evidence, now to reverse its principal spokesman for transportation policy. To do so on the eve of a Congressional election would seem particularly undesirable. Therefore, unless the President is prepared to risk Secretary Volpe’s resignation, I would recommend that he sign the Railpax bill.”

FRA’s Jim McClellan later recalled being summoned to the White House for a meeting with staff to discuss the bill: “The arguments went back and forth with a lot of focus on the numbers, and I weighed in as appropriate. When one key staffer cited a Stanford University study that showed that passenger trains lost a lot of money, I dismissed the results as biased because the study was funded by the antipassenger Southern Pacific. The Stanford study was actually pretty good, but the goal was to win the argument, not to discover the truth.”[46]

The White House had reorganized on July 1, 1970, and the Bureau of the Budget had a new name (Office of Management and Budget, or OMB), and a new Director, George Shultz. Shultz sent President Nixon a memo making strong arguments against the bill and urging a veto: “Railpax, with a majority of its directors appointed by the President, would inevitably have its deficits, its service problems, and its other headaches laid at the feet of the President. The Government would be charged with ‘running the railroads,’ without the necessary authority to improve any of the problems and with all the factors which led to their present plight built into their future operation…In spite of the public position of the Secretary of Transportation in favor of the bill, I feel the bill is bad enough to veto.”[47]

Paul McCracken, the chairman of Nixon’s Council of Economic Advisers, also urged a veto: “…this bill appropriates substantial funds for an enterprise with little economic justification. The funds appropriated are already twice as large as those in the original bill. However, even at this higher funding level, there is the real prospect that future budgets will be saddled with commitments which it ought to be our responsibility to spell out now. For those reasons we strongly urge the President to veto this bill. If, however, he is not prepared to do this, his signing message should contain a clear commitment that the Federal capital contribution to the Corporation will be limited to the amount specified in the bill, that rail passenger service will have to stand or fall on its economic merits, and that this bill implies no claim on future budgets.”[48]

By this point, the bill’s deadline was growing near, and Nixon hit the road on the 27th to go on a multi-day campaign swing (Florida-Texas-Illinois-Minnesota-Nebraska-California). Speaking of politics, White House legislative liaison Bill Timmons notified Ehrlichman’s office that “We did not alert Republicans on Capitol Hill that the bill might be vetoed. Therefore, a veto could embarrass some of our friends who supported the legislation” and said that a veto could hurt candidates like Prouty, Lowell Weicker (R-CT), and Hugh Scott (R-PA). He also said that, as of October 29, rumors of a possible veto were circulating in the press, and “We can expect Democratic charges to hit the papers this weekend. (I strongly suspect DOT is building up pressure).”[49]

On Friday, October 30, Nixon spent the day at his “Western White House” in San Clemente, California, along with his senior aides (Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Kissinger, Ziegler, Rose Mary Woods). Back in Washington, OMB’s Shultz got a call from Volpe, who said that a newspaper in St. Paul, Minnesota was reporting that Shultz was opposed to the bill and that, therefore, Nixon was going to veto it. Volpe told Shultz that he took this to mean that he should not bother sending the president his own arguments in favor of the bill, but Shultz told Volpe to send his memo to the White House anyway.[50] Volpe tried to call Nixon at about 4:30 p.m. Eastern time (1:30 in California) but Nixon did not take the call.

Volpe sent his memo to Nixon that day. It assured the President that “all of the indications that we have are that the Rail Passenger Corporation will be economically viable by the third of fourth year of operation and will be providing sound transportation alternatives to aviation and highway movement. The operations of the Corporation can be expected to turn a relatively small initial year loss of $30-40 million – the current level in the preliminary network – into an operating profit by the third year…the economic prospects make the hazard of future demands for Federal support relatively low.”[51]

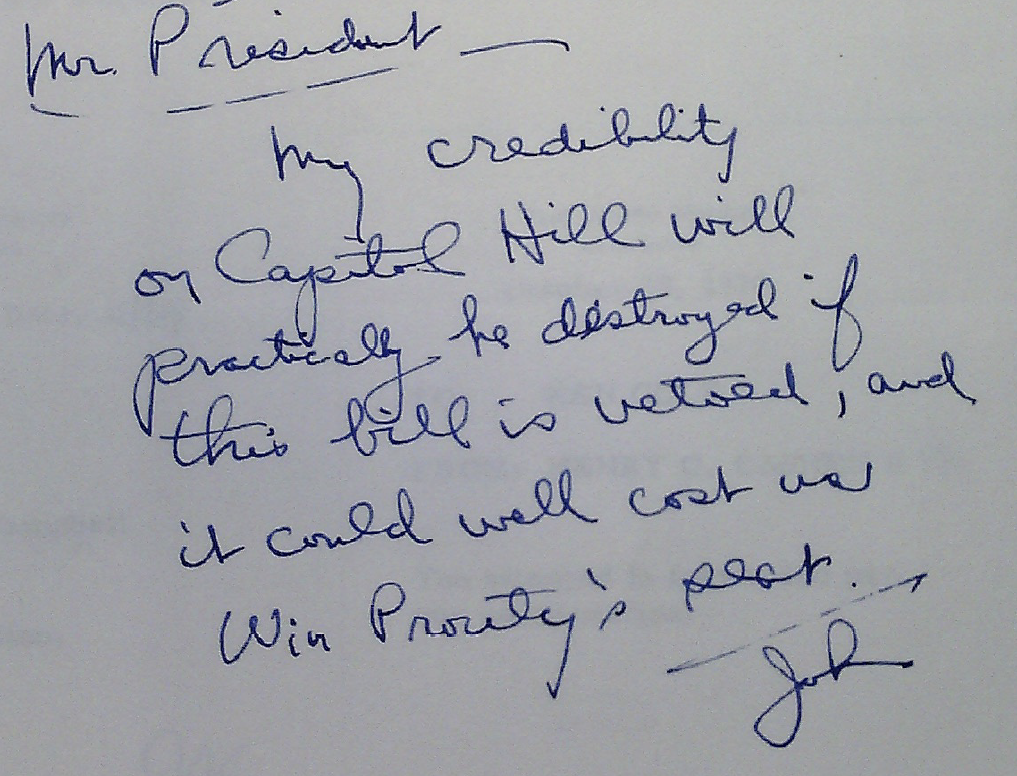

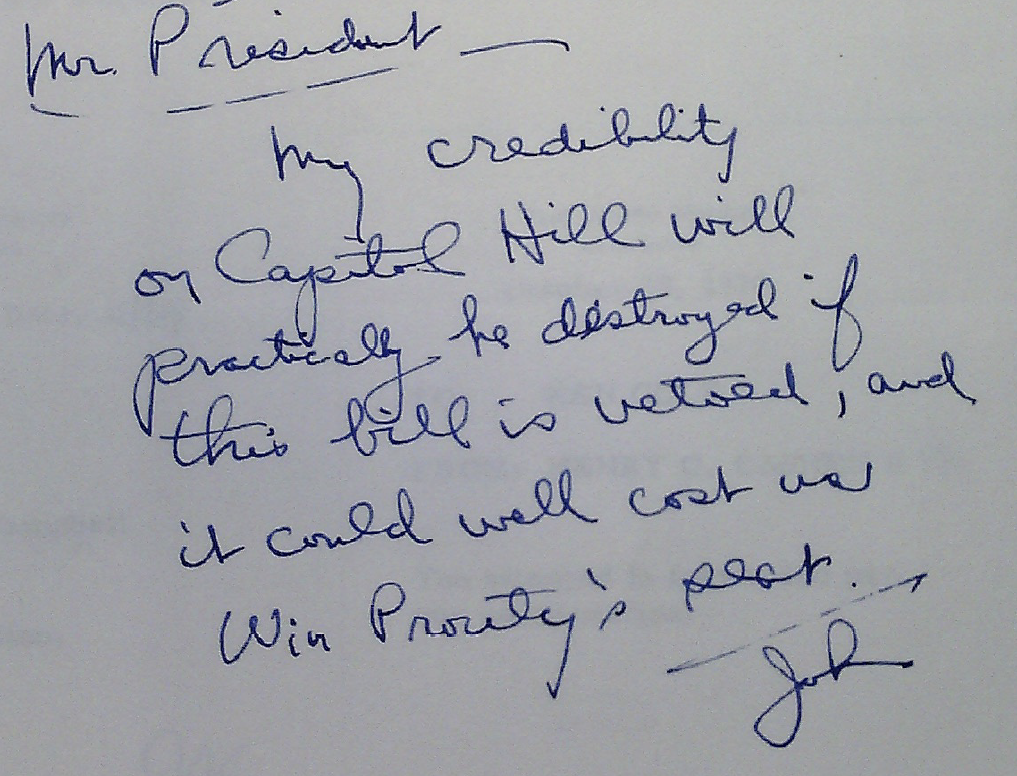

Volpe went on to list other reasons that the bill should be signed (expectations on the Hill, the need to keep train service going to head off additional airport and highway spending arguments, and the continued need to do something to lift the financial burden from the Penn Central and other private railroads). But he added a handwritten postscript: “Mr. President – My credibility on Capitol Hill will practically be destroyed if this bill is vetoed, and it could well cost us Win Prouty’s seat. John.”

After weighing all the arguments, Nixon decided to get it over with and signed the bill into law at some point on the 30th. There was no ceremony, and no signing statement, only a one-sentence announcement from the press secretary that he had signed the bill. Because there was no statement, Nixon was unable to comply with CEA’s wishes that a signing statement clearly lay out the expectation of profitability and that no subsidies after the initial tranche of aid would be forthcoming.

(How was Volpe able to circumvent Ehrlichman from 3,000 miles away? Volpe’s then-legal counsel, Joseph Bosco, later wrote that “Volpe was able to succeed in that hostile environment partly because he had a secret White House ally: fellow co-religionist and daily communicant Rose Mary Woods, Nixon’s personal secretary. She had had her own problems with Nixon’s inner circle and saw Volpe as a kindred spirit. At critical times, she was able to get him the direct access to Nixon that his staff denied to all Cabinet officers and even to Agnew. (After the railroad legislation turnaround, an irate Ehrlichman called Volpe to complain, ‘I don’t know how you got to the president, but he’s decided to sign your bill after all.’)”)[52]

The Nixon Administration had avoided its worst-case scenario of having to sign a bill (like that originally proposed by Senator Hartke) that promised unlimited, open-ended operating subsidies for private railroads to operate money-losing passenger service indefinitely. And they accomplished their two short-term political objectives: needing to be seen “doing something” about the passenger train problem, and preventing the issue from blowing up three days before the midterm elections.

But by signing the Railpax bill, Nixon only bought a temporary (three-year) reprieve from having to deal with the difficult issues relating to passenger trains that had been building up for forty years.

Upon signature, the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970 became Public Law 91-518 and set a startup date for the National Railroad Passenger Corporation of May 1, 1971.

To be continued…

[1] United States. Interstate Commerce Commission. “Railroad Passenger Train Deficit” (Proceeding No. 31954), 1958, at p. 72. Available online at https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015018275076

[2] United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Commerce. National Transportation Policy (Report of the Special Study Group on Transportation Policies in the United States). Senate Report No. 445, 87th Congress. Washington: GPO 1961 p. 326. Available online at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015023117982&view=1up&seq=9

[3] National Transportation Policy p. 328.

[4] Randal O’Toole, Romance of the Rails: Why the Passenger Trains We Love Are Not the Transportation We Need. Washington: Cato Institute, 2018 chapter 9.

[5] United States. Interstate Commerce Commission. “Investigation of Costs of Intercity Passenger Rail Service.” July 1969, page ii. Available online at https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015004568708?urlappend=%3Bseq=7

[6] United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Commerce. Passenger Train Service Legislation (Hearings before the Subcommittee on Surface Transportation, September 23, 24, and 25, 1969) p. 1. Available online at https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b644054

[7] Email from Robert Gallamore to the author, October 29, 2020, and Northeast Corridor Transportation Project Report (April 1970) by the Office of High Speed Ground Transportation, U.S. Department of Transportation.

[8] Jim McClellan, My Life With Trains (Railroads Past and Present). Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017. Chapter 8.

[9] My Life With Trains chapter 8.

[10] Email from Robert Gallamore to the author, October 29, 2020.

[11] Passenger Train Service Legislation p. 143.

[12] My Life With Trains chapter 8.

[13] Passenger Train Service Legislation p. 143.

[14] Joseph A. Bosco, “Volpe might have stopped Watergate.” POLITICO (online ed.), August 7, 2013 4:32 p.m. Retrieved February 7, 2021 from https://www.politico.com/story/2013/08/opinion-joseph-bosco-richard-nixon-watergate-095308

[15] My Life With Trains chapter 8.

[16] Recounted in memo from Robert P. Mayo to John Ehrlichman, dated February 14 or 16, 1970 (both date stamps are on the document), subject line “DOT’s Railpax proposal.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “Beginning – 4/1/70,” Nixon Library.

[17] Robert Lindsey, “Volpe’s Rail Plan Finds Opposition.” The New York Times, January 20, 1970 p. 85.

[18] Memo from John D. Ehrlichman to Richard Nixon, January 23, 1970, subject “Background and present status with respect to Rail Passenger Service.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “Beginning – 4/1/70,” Nixon Library.

[19] Memo from John D. Ehrlichman to Richard Nixon, January 23, 1970, subject “Rail Passenger Service.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “Beginning – 4/1/70,” Nixon Library.

[20] Memo from Daniel Patrick Moynihan to John D. Ehrlichman, January 28, 1970, no subject line. Original located in White House Central Files: Files of Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Box 35, Folder “Railpax [2 of 2], Nixon Library.

[21] Memo from John Volpe to Richard Nixon, undated, subject line “Rail Passenger Service.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “Beginning – 4/1/70,” Nixon Library.

[22] Memo from John D. Ehrlichman to Richard Nixon, February 4, 1970, subject line “Sec. Volpe memoranda.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “Beginning – 4/1/70,” Nixon Library.

[23] Memo from Tod R. Hullin to John D. Ehrlichman, February 17, 1970, subject line “Follow-up to the Railpax presentation by Jim Beggs and Charles Baker, Thursday, February 12, 2:00 p.m.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “Beginning – 4/1/70,” Nixon Library.

[24] Letter from James M. Beggs to John D. Ehrlichman, February 18, 1970, subject line “Rail Passenger Service,” and accompanying document of the same name. (The route-by-route analysis is Appendix C.) Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “Beginning – 4/1/70,” Nixon Library.

[25] Memo from Robert P. Mayo to John D. Ehrlichman, February 23, 1970, subject line “Rail Passenger Service.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “Beginning – 4/1/70,” Nixon Library.

[26] Memo from John D. Ehrlichman to Richard Nixon, March 2, 1970, subject line “Status of DOT’s Rail Passenger Service Proposals.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “Beginning – 4/1/70,” Nixon Library.

[27] Dan Rather and Gary Paul Gates. The Palace Guard. New York: Warner Books, 1974 (quote is from 1975 Warner Paperback Library edition, p. 225).

[28] Email from Steve Ditmeyer to the author, October 26, 2020.

[29] Memo from John Volpe to Richard Nixon, October 30, 1970, subject line “Rail Passenger Legislation.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “5/1/70 – 11/5/70,” Nixon Library.

[30] “Corporation Created to Operate Rail Passenger System.” In CQ Almanac 1970, 26th ed., 09-804-09-809. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1971. https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/cqal70-1291580.

[31] Thanks to Alan Pisarski for pointing this out while the article was still in draft form.

[32] “U.S. Rail Aid Is Set For Intercity Lines.” The New York Times, April 29, 1970 p. 1.

[33] Congressional Record (bound edition), May 6, 1970 p. 14274.

[34] Congressional Record (bound edition), May 6, 1970, p. 14279.

[35] Congressional Record (bound edition), May 6, 1970 – quote is p. 14281 and vote is p. 14287.

[36] United States. Congress. House of Representatives. Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. Passenger Train Service (Supplemental Hearings before the Subcommittee on Transportation and Aeronautics, June 2, 3, and 4, 1970) pp. 67-69.

[37] Passenger Train Service p. 60

[38] Passenger Train Service p. 135.

[39] Memo from Robert F. Bennett to Dick Cook, October 9, 1970, no subject line. Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “5/1/70 – 11/5/70,” Nixon Library.

[40] Memo from John D. Ehrlichman to John A. Volpe, October 16, 1970, no subject line. Carbon copy of original located in White House Central Files: Staff Member and Office File, Kenneth Cole series, box 6, folder “Chron File: October 1970,” Nixon Library.

[41] Congressional Record (bound edition), October 13, 1970 pp. 36594-36595.

[42] Congressional Record (bound edition), October 14, 1970 pp. 36894-36895.

[43] “Statement of Secretary of Transportation John A. Volpe on the Passage by the House of Representatives of the National Rail Passenger Service Act,” October 14, 1970.

[44] Unsigned memo to “RZ” (presumably Ron Ziegler), October 21, 1970. Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “5/1/70 – 11/5/70,” Nixon Library.

[45] Memo from Peter Flanigan to John Ehrlichman, October 27, 1970 (no subject line). Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “5/1/70 – 11/5/70,” Nixon Library.

[46] My Life With Trains chapter 8.

[47] Memorandum from OMB Director George Shultz to President Nixon, undated, subject line “Railpax.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “5/1/70 – 11/5/70,” Nixon Library.

[48] Letter from Paul W. McCracken to OMB official Wilfred Rommel, October 27, 1970. Nixon Library.

[49] Memo from William E. Timmons to Ken Cole, October 29, 1970, subject line “Railpax.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “5/1/70 – 11/5/70,” Nixon Library.

[50] This conversation is recounted secondhand in a memo from Ken Cole to John Ehrlichman, October 30, 1970 (no subject line). Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “5/1/70 – 11/5/70,” Nixon Library.

[51] Memo from John Volpe to Richard Nixon, October 30, 1970, subject line “Rail Passenger Legislation.” Original located in White House Central Files: Subject Files, Series TN 4 (Railroads), Box 6, Folder “5/1/70 – 11/5/70,” Nixon Library.

[52] Bosco, “Volpe might have stopped Watergate.”