This article is a part of our series From Lighthouses to Electric Chargers: A Presidential Series on Transportation Innovations

Every U.S. presidential election has its own twist. In 1824, Andrew Jackson received 41% of the popular vote while the second place finisher, John Quincy Adams, received 31%. Although Jackson received more electoral votes than any other candidate, he did not receive the needed majority. That triggered the 12th amendment which stipulates the U.S. House of Representatives selects the president from among the top three vote getters.

Henry Clay, the speaker of the House, helped secure enough votes for Adams to win on the first House ballot. In return, Adams appointed Clay as the Secretary of State, a position that was seen as a steppingstone to the presidency. The third, fourth, fifth, and sixth presidents (Jefferson, Madison, Monroe as well as Adams) had all been secretaries of state.

Jackson was known for his fiery temper and dominating personality. Outraged over the House vote, he referred to the “corrupt bargain” that overturned the “will of the people.” We do not know exactly what transpired between Adams and Clay, but Clay was clearly comfortable that Adams would be supportive of his vision for America, of which transportation played an integral role. In fact, Clay’s vision would become the centerpiece of the new president’s domestic agenda.

Henry Clay

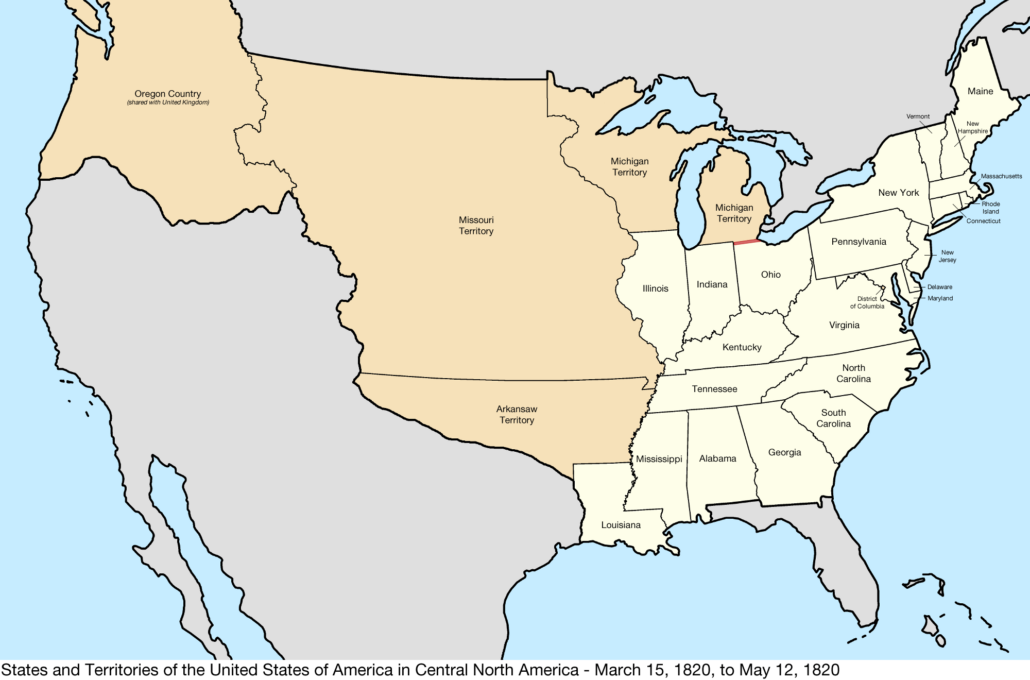

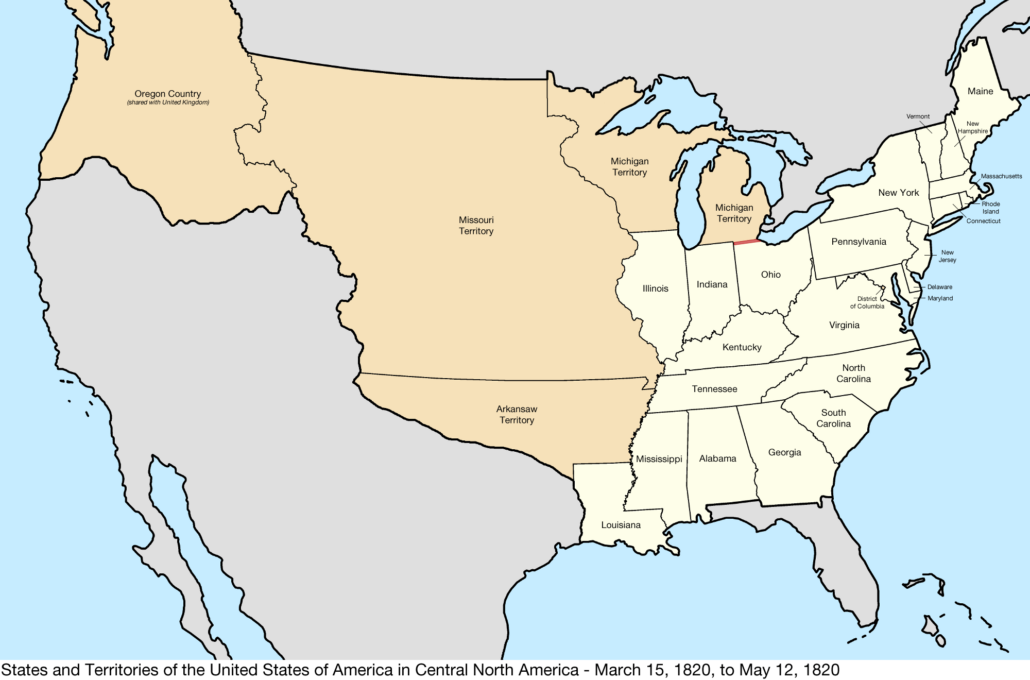

Henry Clay hailed from Kentucky which was a western state in 1820, as shown in this map.

Clay’s program comprised three main components: tariffs, land sales, and transportation. High tariffs would be imposed on imported goods to shield American industries from foreign competition and encourage domestic manufacturing. Revenue from these tariffs, along with proceeds from the sale of public lands, would fund the development of roads and canals, collectively referred to as “internal improvements.” Clay viewed these infrastructure projects not only as a means to stimulate growth in the western regions but also as a way to integrate and fortify the American economy.

The construction of new canals and roads played a pivotal role because enhancing the speed and reliability of moving goods, would facilitate the seamless flow of agricultural products and raw materials (such as grains and cotton) from the southern and western states to the industrial centers in the north. In return, manufactured goods would be transported back to the south and west.

Adams’ Ambitious Program

In his March 1825 inaugural address, President John Quincy Adams argued for an expansive use of federal resources, saying that the exercise of powers “is a duty as sacred and indispensable as the usurpation of powers not granted is criminal and odious.” He talked about how public works projects would bring prosperity and glory, the same way that the roads and aqueducts had done for ancient Rome.

Adams’ ambitious economic development agenda was a break from the more cautious approach to federal power embodied by his predecessors. President Adams was not a new convert in calling for a stronger federal role, though. As a U.S. Senator in 1807, he had introduced a resolution that advocated building roads, removing obstructions in rivers, and building canals.

During the terms of the first few presidential administrations, a consensus had formed in Congress that the Constitution authorized the federal government to construct roads and canals within the territories where there was no state sovereignty. But that consensus did not extend to construction within the states. During the War of 1812, however, Americans became more accustomed to relying upon the federal government (just as they would during the Depression of the 1930s). As a result, members of Congress became somewhat less suspicious about using the federal government to promote the general welfare of the country.

More money was appropriated for internal improvements during Adams’ administration than had been granted during any previous administration. He won congressional approval for the 365-mile long Chesapeake and Ohio Canal that would connect the Chesapeake Bay (bordering Virginia and Maryland) with Pittsburgh on the Ohio River. The canal never would reach Pittsburgh; instead, it would terminate 180 miles west of the Chesapeake at Cumberland in Maryland.

After the canal opened in the 1830s, mule teams pulled boats an average of about three miles per hour, certainly not a remarkable speed by today’s standards, but the canal proved to be an important route for shipping coal between the Allegheny Mountains and port cities.

Today the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park tells the story of the canal’s role in western expansion, the Civil War, immigration, industry and commerce.

Today the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park tells the story of the canal’s role in western expansion, the Civil War, immigration, industry and commerce.

In December 1825, as part of his first Annual Message to Congress, President Adams reported that surveys were “ascertaining the practicability” of canals and roads, but that the progress of infrastructure improvements “has been delayed by the want of suitable officers for superintending them.” (Today, the U.S. continues to face similar workforce shortages. A recent headline in the Seattle Times stated, “Lack of Civil Engineers a Bottleneck for WA’s Large Transportation Projects.”)

Adams also told Congress in his message that progress was made on planning “a national road from this city to New Orleans.” However, Congress thwarted many of Adam’s proposals including constructing a 1,000 mile road to New Orleans, building a national astronomical observatory, and setting up a national university.

Congress opposed many of Adams’ internal improvements in the 1820s for numerous reasons. For one, Jackson supporters did not want the president to succeed and were not interested in giving him accomplishments upon which he could run for re-election. Adams’ personality and persuasive skills did not help his cause, either. Although widely considered brilliant (he spoke French, Dutch, German, Greek, and Latin), John Quincy Adams was not known for his warmth. The son of the second U.S. president was derisively described as a “chip off the old iceberg.“

Some legislators opposed the federal government mingling into what was considered state affairs while others were concerned about the potential for corruption associated with major projects. Southern states, in particular, opposed the high tariffs that were a cornerstone of Clay’s plan. They did not want to pay more for imported goods or have to pay the higher prices that northern manufacturers were charging.

Many southerners were particularly wary of the expanding the federal government powers, fearing that if Congress could authorize the construction of roads and canals, it might take action that would undermine the southern economy and threaten its lifestyle. A central government with the power to build internal improvements, they reasoned, might have the audacity to free the nation’s more than 1.5 million slaves.

This article is a part of our series From Lighthouses to Electric Chargers: A Presidential Series on Transportation Innovations

Today the

Today the