In the early 19th century, Dewitt Clinton, the mayor of New York City and later the governor of New York, was a tireless advocate for building a canal that would connect Albany (located on the Hudson River) with Buffalo (on Lake Erie.)

A canal would provide a water route from the Atlantic Ocean to the midwest. At the time, trade between the eastern seaboard and the Northwest Territories (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Ohio) was limited because transportation via land was neither cost-effective nor reliable. The timber, minerals, and fertile land for farming near the Great Lakes, lay out of reach.

New York’s commercial interests had their own incentives for building the canal. It would provide an economic boom to communities along the canal and help attract more business to the Port of New York. After the revolution, New York had the nation’s fourth busiest port, lagging behind Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston.

In 1809 two elected officials from New York, William Kirkpatrick and Joshua Forman, met with President Jefferson to obtain his support for the canal. Kirkpatrick remembered that he extolled the canal’s benefits, explaining the “important advantages it offered to the nation as inducements to undertake it – enhancing the value of their lands – settling the frontier – opening a channel of commerce for the western country to our own seaports – a military way in time of war, and a bond of union to the states.”

The canal would be by far the longest artificial waterway and the greatest public works project undertaken in the country’s short history.

Two years earlier, President Jefferson had signed a bill to start work on the National Road, connecting Maryland with the Ohio River. Normally, he did not think the U.S. constitution gave the federal government the power to build canals and roads, but he deemed the road an exception because it would be financed through the sale of public lands in Ohio, and it would have to obtain approval of the states through which it passed.

When Jefferson met with the Erie Canal advocates, he lamented the lack of funds available to extend the Potomac Canal and reportedly said, “you talk of making a canal 350 miles through the wilderness–it is a little short of madness to think of it at this day.” Forman remembered that Jefferson did not oppose it, he just thought it was premature, saying, “it was a very fine project, and might be executed a century hence.”

Although Jefferson’s words dampened the enthusiasm of New York’s state legislators, the state did authorize $20,000 for a detailed survey, and eight years later approved state funds for its construction.

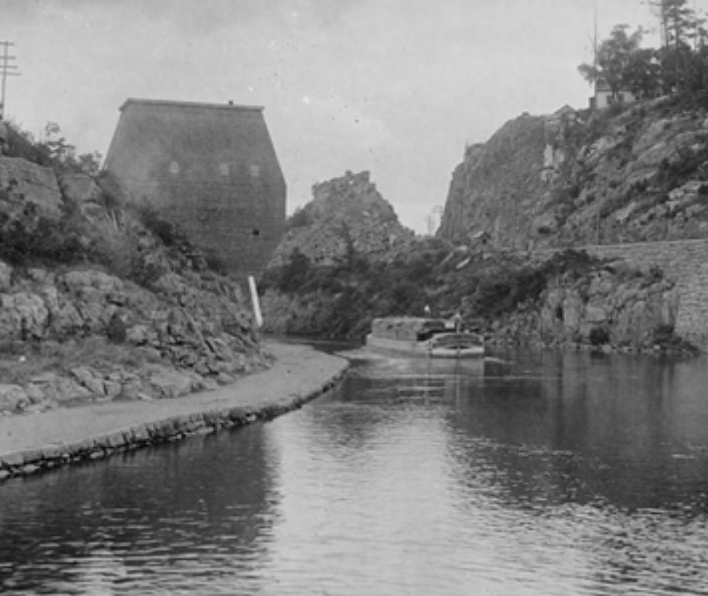

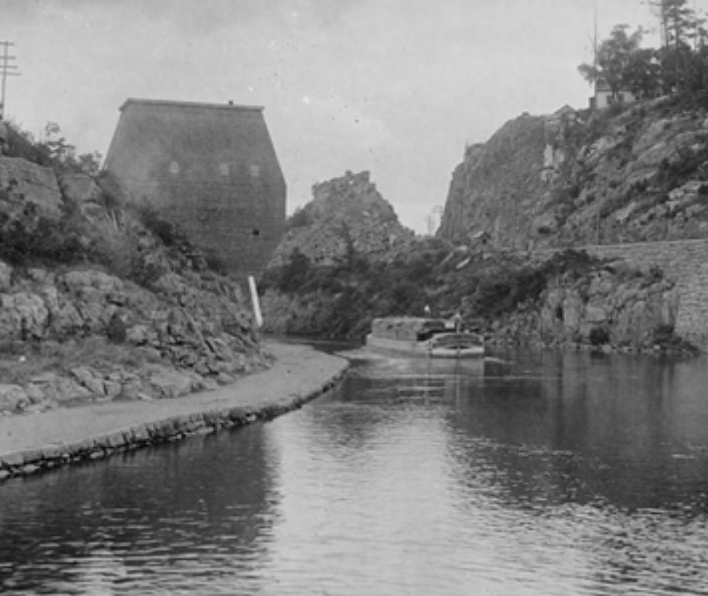

Photo Credit: Library of Congress.

Before the 363-mile long canal opened, Governor Clinton predicted, “The city will, in the course of time, become the granary of the world, the emporium of commerce, the seat of manufactures, the focus of great moneyed operations.” Although the canal was only 4-feet deep and 40-feet wide, Clinton was right about the transformation that would occur.

Manhattan, and its neighboring city of Brooklyn, soon became America’s dominant port with more than two-thirds of the nation’s imports coming into their harbor. Thanks to the canal, the region became the nation’s hub for wheat from the northwest, cotton from the south, sugar from the Caribbean, silver from Mexico, and tea from China. Goods were stored and traded along the waterfront and many New Yorkers made their fortunes.

The canal and resulting trade transformed New York into a manufacturing powerhouse featuring a thriving ship-building and garment industry. Since the traders and manufacturers needed financing, New York also became the nation’s financial center and later the preferred location for corporate headquarters. With all of the job opportunities, Manhattan’s population rose from 123,000 in 1820 to 814,000 in 1860. Likewise, the number of Brooklyn residents multiplied by 25 during that period, rising from 11,000 to 279,000.

The Erie Canal also reshaped the rest of the state. Nearly every major city in New York falls along the trade route established by the Erie Canal, from New York City to Albany, through Schenectady, Utica, and Syracuse, to Rochester and Buffalo.

Erie Canal in Syracuse (early 1900s). Source: Library of Congress

Because the cost of shipping goods via the canal was only about one-tenth the price of shipping via roads, the canal also reshaped the nation. Travel time could be measured in days rather than weeks. That is why Michigan’s population went from less than 7,500 in 1820 to nearly 400,000 in 1850 and Indiana’s population rose from less than 150,000 in 1820 to nearly a million in 1850.

Without a doubt and by any measure, this transportation project, built 150 miles north of New York City was one of the most successful public economic development initiatives in U.S. history.

In an 1822 letter, more than two decades after he left office, Thomas Jefferson was excited about the anticipated opening of the canal. He wrote in a letter to DeWitt Clinton:

“N. York has anticipated by a full century the ordinary progress of improvement. This great work suggests a question both curious & difficult, as to the comparative capability of nations to execute great enterprises. It is not from a greater surplus of produce after supplying their own wants, for in this N.Y. is not beyond some other states. Is it from other sources of industry additional to her produce? This may be. Or is it a moral superiority? A sounder calculating mind as to the most profitable employment of surplus, by improvement of capital instead of useless consumption?”

In this letter, Jefferson (who was both a philosopher and statesman) asked a question that still resonates today when we think about how we should invest our resources. Should we prioritize our short-term or long-term interests? Decision-makers still grapple with that question, every day, when making choices about maintaining infrastructure, setting fares and tolls, preparing capital programs, and investing in expansion projects.

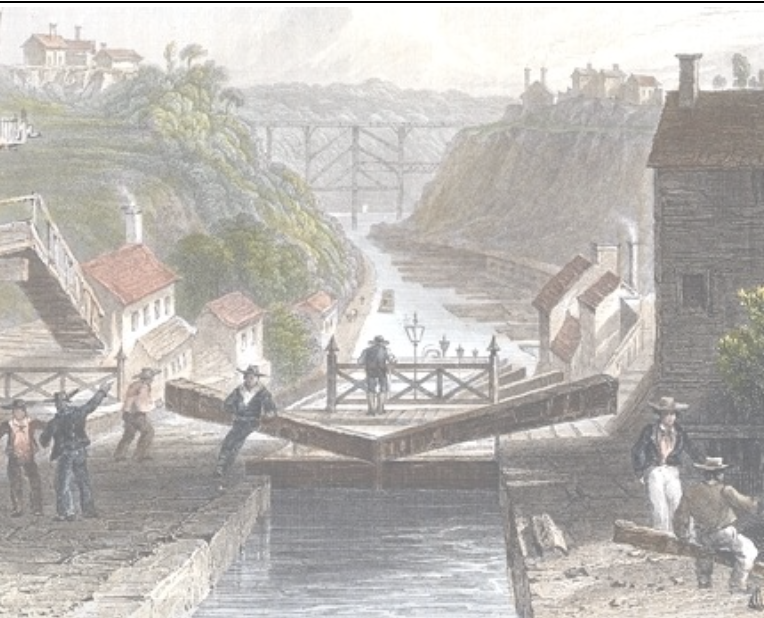

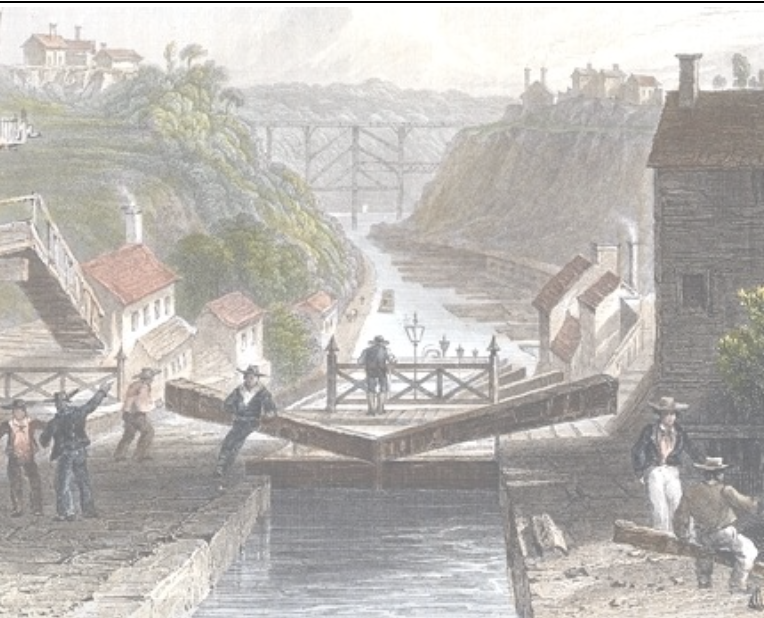

The Erie Canal, engraved after a sketch by W.H. Bartlett.

Check out all of the articles in our Presidential Series by visiting our archive!