Parts of this article were published in altered form in Transportation Weekly in 2009 and 2014.

(Introductory Note: On his first day as a rookie reporter for the national desk of the Washington Post in January 1977, T.R. Reid was assigned to follow a bill from introduction through whatever its eventual fate at the end of the 95th Congress might be. His editor picked the bill that became the Inland Waterways Revenue Act of 1978, so not only did the bill receive unusual publicity throughout 1977-1978 from occasional front page stories in the Post, but Reid also turned his stories into a book about the enactment of the bill, entitled Congressional Odyssey: The Saga of a Senate Bill. Parts of this article draw heavily from that book, and any interested parties really should read the whole thing.)

Prelude – “forever free” navigation

America was originally settled by boat, and the growth of early settlement naturally clustered around natural harbors and inland rivers. Ensuring that access to harbors and navigability of waterways remained safe from natural disasters, decay, and military assaults was a top priority for the British Empire and later for the colonial governments.

The principle that access to these waterways should be free to all goes very far back in American jurisprudence – all the way to the Treaty of Paris (1783) which brought peace with England and formally ended the American Revolution. Article 8 of the Treaty said that “The navigation of the river Mississippi, from its source to the ocean, shall forever remain free and open to the subjects of Great Britain and the citizens of the United States.”

Four years later, the most important statute of 18th-century America, the Northwest Ordinance, codified and expanded on this principle, stating in Article 4 that “The navigable waters leading into the Mississippi and St. Lawrence, and the carrying places between the same, shall be common highways and forever free, as well to the inhabitants of the said territory as to the citizens of the United States, and those of any other States that may be admitted into the confederacy, without any tax, impost, or duty therefor.”

“[F]orever free” – as Prince wrote, forever is “a mighty long time” – but in this instance, the principle of tax-free and toll-free navigability of inland waterways stayed in place for almost 200 years – which, from a legislative point of view, is practically forever.

Until Pete Domenici came along.

In 1977, Senator Pete Domenici (R-NM) was nearing the end of his first term in the Senate and was up for re-election in 1978. Reid recalls how Domenici was 100th in seniority as a freshman and was given an unasked-for assignment to the Public Works Committee – and to add insult to injury, he was placed on the Water Resources subcommittee, which handled the “rivers and harbors” legislation (New Mexico is notable for its lack of both).[1]

The 1824 Gibbons v. Ogden decision from the U.S. Supreme Court (22 U.S. 1) gave the federal government complete authority to regulate interstate commerce on waterways (Daniel Webster was the victorious attorney arguing Gibbons’ case). Less than three months after that decision was handed down, Congress enacted the act of May 24, 1824 (4 Stat. 32) authorizing the President to improve the navigation of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and appropriating $75,000 towards that purpose.

Congress quickly took to water with the same affinity as do ducks, and by the mid-twentieth century, legislators were in love with authorizing and appropriating funds for their own pet river and harbor projects carried out by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Starting with President Kennedy and Johnson proposed to recoup some of the Corps’ costs of inland waterways through user charges, in every one of their budget proposals from fiscal 1963 through 1970, and then Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter resumed the call in the fiscal 1977, 1978, and 1979 budgets.[2]

But the problem was always Congress. In the mid-1970s, things were no different than they had been in 1959, when former UPI Senate gallery correspondent Allen Drury captured the scene in Advise and Consent (the best-ever novel written about Congress, by far). Drury described a boisterous hearing of the Senate Appropriations subcommittee on Rivers and Harbors:

Confronted by these determined and forceful gentlemen, the Corps of Engineers is not in the least dismayed. Serene in the knowledge that they are proprietors of the lobby which is, year in and year out, the most ruthless, the most effective and untouchable on Capitol Hill, its high-ranking officers are going through this annual charade with unperturbed suavity. In the comfortable Siamese-twin relationship which exists between the Corps and the Appropriations committees of the two houses, the Engineers know that when they reach to scratch their own backs they will also give solace to some solon, and that when Senator or Congressman in turn relieves his own itch he will in the process ease the Corps of Engineers. In close harmony and perfect accord they will spend the public monies together and both will be happy…not least the Engineers, for of course all these new funds and new projects will require new personnel to administer them, and so the always-swelling empire will continue its steady, inexorable growth. In the practical world of Washington the Corps and the Congress, it might be said, have each other firmly by a tender and important part of the anatomy; and in case either side should ever attempt to get out of line, a little squeeze is all that is necessary to restore a perfect understanding.[3]

(This coziness between the authorizing and appropriating committees on Capitol Hill and the career Army staff of the Corps occasionally led some observers to conclude that the Corps really belonged to the legislative branch of government, not the executive branch.)

Domenici pushes for user fees

As Domenici learned more about the issues before his subcommittee, he quickly discovered that while the barge industry got great benefit from the hundreds of millions of dollars appropriated by Congress every year to the Corps of Engineers to keep rivers and other inland waterways dredged and cleared, the barge industry paid nothing in the way of taxes or fees to pay for these capital improvement costs.

While this may have made sense as a federal policy in the days when inland waterways were the only way to carry significant amounts of cargo, the barge industry was now competing directly with the railroad industry in many markets for transportation of bulk cargoes – and the railroads had to pay for all of their own capital costs. In addition, the inland waterways network stops at the Missouri River – any shippers west of there but east of Oregon are solely dependent on railroads to transport bulk cargo and thus gained no benefit from federal barge subsidies, making it somewhat of a regional issue.

Reid describes a series of Senate hearings in 1976 on replacement of a large lock and dam during which a bored Domenici decided to ask every witness their thoughts on a potential user fee system for barges, culminating with this scene:

On the last day of the hearings, a barge-line executive who had grown progressively angrier at Domenici’s questions could contain himself no longer. “How come you’re so interested?” the man shouted from his seat in the audience. “You don’t have any waterways in New Mexico. What business is it of yours?”

All of a sudden, Domenici’s temper was fully ignited. “Jesus, that got me mad,” Domenici recalled later. “In fact, it was that guy, shouting at me, that cemented it in my head, that I would take this on. I was just – I had a combination of violent anger and a burning desire to retort. So I said, ‘Mister, you’re going to find out what business it is of mine’ and I got up and walked out.”[4]

When the next Congress began, Domenici introduced legislation (S. 790, 95th Congress) that did several things in very clever ways. First of all, it authorized user fees to be levied on barges using the Corps-maintained inland waterways network. However, the amount of the fees was not set. Instead, the goal was eventually to recover 100 percent of the Corps’ annual operational costs for the waterways system and 50 percent of the Corps’ annual inland waterways expenses – the total amount of the fees levied would be raised or lowered administratively each year based on half of the level of enacted appropriation, which would give the barge industry a large incentive to support restrained growth in Corps spending. To ensure that the industry could not ignore his proposal completely, S. 790 also included the top priority of the barge industry – a $400 million authorization for the Corps to replace the rapidly decaying Lock and Dam 26 on the Mississippi River at Alton, Illinois, without which one cannot pass from the Upper Mississippi to the Lower Mississippi.

Most cleverly of all, by structuring his bill as a true user fee and by leading the bill off with a spending authorization for the lock and dam, Domenici got the Senate Parliamentarian to refer the bill to his own Public Works Committee, not to the Commerce Committee (which has interstate transportation generally) and not to the Finance Committee (which oversees taxes).

The final distinction is crucial. Under the original Domenici bill, the Parliamentarian determined that the fees would not be taxes. Had they been classified as taxes, they would have (a.) gone to the Finance Committee and (b.) been forced to wait for a House-passed tax bill, since under the Origination Clause of the Constitution, “All bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives…”

In addition, there is an equally important distinction. Under the definitions used in 1977 and today, taxes create budget receipts, “collections from the public that result from the exercise of the Government’s sovereign or governmental powers” while true user fees are classified as offsetting collections which can be credited to individual appropriations accounts, and usually count as offsets to new budget authority, not as tax receipts.[5]

The distinction: taxes are automatically deposited in the general fund, and the only way to correlate a new tax with a specific spending program is by the creation of a new trust fund account or other special fund to which those receipts can then be transferred. Real user fees can be credited against existing appropriations accounts and eliminate that amount of spending from the budget. Accordingly, the original Domenici plan did not create any kind of new trust fund account to hold the proceeds of the user fees.

In order to get the leverage he needed to keep the barge industry and its allies from simply severing the Lock and Dam 26 authorization from the new user fee, Domenici needed lobbyists and leverage. The lobbyists came courtesy of the Western Railroads Association, who were actively supporting any kind of user fee that would, in their opinion, start to level the playing field between railroads and barges (though they were opposed to the repair of Lock and Dam 26). Reid tells of how the railroads not only lobbied overtly for the change, they also set up a shell association (the “Council for a Sound Waterways Policy”) through which they funneled money to environmental organizations to help subsidize their lobbying activities in favor of the user fees.[6]

Jimmy Carter engages in the “water wars”

The leverage came from the Carter Administration.

Jimmy Carter entered the Presidency determined to pick a fight with Congress over wasteful spending, and the early battlefield was water resources projects. After just one month in office, Carter notified Congress that he was killing funding for 19 water projects that “which now appear unsupportable on economic, environmental, and/or safety grounds” and was reviewing 300 more.[7]

The pushback from Congress was so intense that he had to send a somewhat apologetic letter to legislators a month later promising that “Projects will be assessed on an individual basis, based upon criteria developed in close consultation with Congress.”[8]

Carter’s final review of the water projects came on April 18, 1977, and was accompanied by a new statement of policy, which included these lines: “the users of the Nation’s waterways pay nothing for their construction or maintenance. Today I am recommending continuation of some waterway projects, but I will work with the Congress to develop a system to recoup the costs from the beneficiaries. It is essential as a test of economic demand for existing and future facilities and in assuring a balanced transportation system that the beneficiaries of waterway projects pay their fair share of both construction and operating costs.”[9] (Emphasis added.)

The reference to a “balanced transportation system” was key, because it meant that negotiations with Congress over inland waterway system cost recoupment would not be handled by the Army Corps of Engineers, which designs, builds, and maintains the projects, and to whom Congress appropriates the annual funding for all of the above. Instead, the President’s negotiator would be the man in charge of a balanced transportation system – Transportation Secretary Brock Adams.

(This issue – whether or not the Secretary of Transportation would be in charge of setting cost-benefit standards for all federally-funded transportation projects, including Corps of Engineers navigation projects – had been a key point of contention during Congressional debate on creating DOT in 1966. The final provision – section 7 of Public Law 89-670 – was gutted by Congress, exempting water resource projects and “grant-in-aid programs authorized by law” from the Secretary’s standard-setting ability. Carter was trying to give Adams authority that Congress, a decade earlier, specifically had not wanted the Secretary of Transportation to have.)

Pete Domenici was one of the founding members of the Senate Budget Committee, and during their House counterpart panel’s first full Congress, the House Budget Committee was chaired by then-Rep. Brock Adams (D-WA). Domenici and Adams had become friendly and stayed in touch, and Adams came into DOT sympathetic to Domenici’s user fee goals.

Adams lobbied the White House hard to support the Domenici proposal and before Public Works marked up the bill, Adams told the panel on May 2, 1977 that the White House supported the linkage between user fees and replacement of Lock and Dam 26 (though Adams emphasized that the Administration preferred a fuel tax on diesel fuel used by barge tow boats to an actual user fee).

Domenici wins an initial victory; the House pushes back

Public Works then reported the bill with the $420 million authorization for Lock and Dam 26 and with a provision directing a system of user fees to be levied administratively. Adams wrote to Carter on May 9 saying that the Senate Commerce Committee, which got a sequential referral of the bill, might kill the user fees, and that he wanted Carter to give a veto threat to a Lock and Dam 26 authorization that was not accompanied by some kind of cost recoupment.[10]

Carter agreed, and Adams conveyed that threat to the Senate in a letter to the Majority Leader on May 20, 1977, expressing “the President’s very firm intention to veto” a bill without user charges.[11] At a May 25 news conference in Chicago, Carter stated flatly that he would veto a Lock and Dam 26 bill in the absence of cost recoupment.[12]

By the time the full Senate took up the issue in June 1977, the veto threat had opened some eyes (though the Carter Administration had already alienated many in Congress to the point that some Senators were not quite sure if the veto threat was serious). Domenici offered the text of S. 790 as an amendment to a the House-passed omnibus water projects authorization bill (H.R. 5885, 95th Congress), and when an amendment was offered to strike the user fees from the Domenici amendment and instead require an 18-month study of the user fee concept, most observers were stunned to see the amendment fail, 44 yeas to 51 nays. The user fees stayed in the Domenici amendment, which then agreed to by a 71 to 20 margin.[13]

The Senate then passed H.R. 5885, amended, by a vote of 81 to 5, and requested a conference with the House and appointed conferees two days later. But the Ways and Means Committee stymied action in the House, since its chairman, Al Ullman (D-OR), determined that no matter what the Senate thought (and despite the fact that it was fairly clear that the Domenici fees would have passed muster under existing Supreme Court precedents related to the Origination Clause), Ullman felt that the Domenici proposal was a “bill for raising Revenue” and should be automatically and peremptorily rejected by the House for that reason alone.

This process is called giving a bill a “blue slip” (the engrossed resolution of rejection is printed on blue paper), and the House is the final judge of whether or not it will accept or reject a bill based on what the collective membership perceives to be the Constitutional prerogatives of the lower chamber. In practice, it was practically unheard of for the House to fail to back up the Ways and Means chairman if he took to the floor to make a motion to give a Senate bill a blue slip. Reid reports that Speaker O’Neill did not want the bill to die, so he gave the concerned committees two weeks to come up with a new bill that passed Ullman’s test for constitutionality.[14]

The barge lines and their allies in Congress decided that they could support a diesel fuel tax, as originally proposed by the Carter Administration, much more easily than user fees, since the level of a fuel tax would be set in law while the user fees might be subject to annual revision by the executive branch. Reid reports that the barge industry “originally suggested a tax of 1 cent per gallon, but when they brought up that figure in private meetings with Ullman and [Rep. Bizz] Johnson, the Public Works chairman, both members said it was ridiculously low. The smallest tax Ullman thought he could propose without jeopardizing the lock and dam bill was 4 cents per gallon – the same as the federal fuel tax car and truck drivers pay. The barge lines decided to go along.”[15]

At hearings before the Public Works panel in July 1977, the barge industry made that proposal. The Association of American Railroads said that 64 cents per gallon would be a more appropriate level. Adams testified that an eventual 42 cents per gallon would achieve the same financial returns as the user fees proposed by the Senate bill (100 percent of operating costs and 50 percent of capital costs).[16]

When Ways and Means considered the bill the following week, the panel accepted Ullman’s suggestion to set the tax at 4 cents per gallon for the first two years and 6 cents per gallon thereafter – far below the level that would be raised by the Senate bill’s user fees, and a level which would not be automatically increased if the appropriations for the Corps increased. Also, the House bill (H.R. 8309, 95th Congress) still deposited the receipts from the fuel tax in the general fund of the Treasury. But the fix was in, and Ullman’s version passed the House by a vote of 331 to 70 on October 13.[17]

Delays and Senate compromise

In the Senate, Reid reports, Finance Committee chairman Russell Long (D-LA) was eager to compromise with the House on a tax level of around 10 cents per gallon – which would cost the barge lines less than one-quarter what the original Domenici bill would have cost them. But the barge industry refused to compromise on any tax level that exceeded the House-passed level, which irritated Long and which led the pro-user-fee lobby to dig in their heels as well.[18]

The bill languished in Senate limbo for the remainder of 1977 and the start of 1978 with Domenici and Long at a behind-the-scenes impasse: “For Domenici, linkage between the government’s spending on waterways and the charge imposed on waterways users was an essential element of any user-charge bill. Long was reluctant to go along: a linkage requirement, he said, would violate his personal conviction that tax rates should be set by Congress, rather than by a formula in the hands of the executive branch.”[19]

When the bill came to the Senate floor on May 1, 1978, the Senate had to choose between two new plans. Domenici and his partner, Sen. Adlai Stevenson, Jr. (D-IL), had new plan that they had developed with the White House, with two components: a diesel tax starting at 4 cents per gallon and eventually rising to 12 cents per gallon, and a separate capital recovery user fee that would add to the fuel tax receipts until they combined to bring in a fixed percentage of Corps spending each year. Domenici also had a strong letter of support from the White House.[20]

But the wily Long, who had been pushing a 10 cent fuel tax (delayed until after Lock and Dam 26 construction began, which could have been eons) and no cost sharing. On the eve of debate, Long modified his amendment to keep Domenici’s tax rate, but none of the rest of Domenici’s amendment, and presented it as a great victory for Domenici. A somewhat confused Senate defeated Domenici’s plan by a vote of 43 yeas, 47 nays and then adopted Long’s watered-down version by 88 to 2.[21]

Then President Carter issued a flat-out veto threat of the Senate-passed bill at a press conference on May 25:

“Q. Mr. President, if Congress sends you a public works bill with fees on waterway users at the level set by the Senate recently, will you veto that bill, as Secretary Adams said you would? And if so, sir, what alternative solutions would you propose for problems of Alton Lock and Dam 26?

“THE PRESIDENT. I would veto the Senate-passed bill, yes. We asked the Congress to impose water user fees so that we might get back a part of the cost of operating locks, dams, other very expensive waterway facilities, and, also, to get back part of the cost of the original capital investment.

“In my opinion, at the present time, the barge traffic has a major advantage over other forms of transportation. Also, these facilities, when they are modified or built anew, cost very great sums of money. And I believe that it’s proper for the Congress to pass a law that would let very modest user fees be imposed so that those who do use those facilities that are built by the taxpayers all over the country at least partially share in the cost of them. This is the case with other forms of transportation. I think it ought to be the case with water user fees as well.”[22]

Final compromise – a trust fund is created

Carter’s veto threats (against both the Senate-passed version of the bill and the House version’s excessive water project authorizations) stalled the bill for the rest of May, June and July. Over the August recess, Reid reports, Domenici’s staff began negotiating with Long’s chief counsel over the central issue of capital recovery. Eventually, a compromise was reached: Domenici would settle for a 10 cent per gallon diesel tax, while Long agreed to deposit the receipts in a new Inland Waterways Trust Fund from which future Corps of Engineers appropriations “for making construction and rehabilitation expenditures for navigation on the inland and intracoastal waterways of the United States” could be made. Their logic, per Reid, went like this:

The trust-fund idea was a kind of back-door approach to the goal that Domenici had been seeking all along – a limit on the government’s waterways expenditures. Legally, it was no limit at all. [Long’s staff] insisted that the legislation should contain specific language stating that the Waterways expenditures would not be limited to the amount in the trust fund; that is, Congress at any time could spend all the money in the trust fund and still appropriate more money from the Treasury for additional water projects. But [Domenici’s staff] was guessing that, even with such language in the bill, the trust fund would serve, in practice, as a ceiling on waterways expenditures. “If somebody comes up with a big, expensive pork project some year,” [Domenici’s staffer] explained, “and there’s not enough money in the trust fund to pay for it, I don’t think Congress is going to cough up any money from general revenues. I think they’re going to say that project has to wait until there’s more bucks in the fund.”[23]

By the time the principals and interest groups had signed off on the plan, it was October 6, with a target adjournment date of October 14 rapidly approaching. The compromise was a Senate plan, but since it contained a tax, its final legislative vehicle had to bear a House bill number. Long took from his hip pocket a small (41 lines of text) House-passed revenue bill (H.R. 8533, 95th Congress) to allow the Michigan Democratic Party to raise money through charity bingo games without paying federal income tax on the money.

Long substituted his waterways compromise bill for the text of the bingo bill and sent the bill back to the House by voice vote on October 10, and the House accepted the inland waterways bill (which still bore the formal title given the bingo bill upon introduction, since the Senate forgot to amend the bill’s title) under the suspension of the rules (two-thirds vote) procedure by a relatively narrow 287 to 123 vote on October 13 (essentially, the bill passed by thirteen votes).[24]

(For another sterling example of Russell Long’s using a tiny House-passed tax bill to pass a gigantic, unrelated bill in the 95th Congress, see the 60-page Powerplant and Industrial Fuel Use Act of 1978 (Public Law 95-620), the formal title of which is “An Act to amend the Tariff Schedules of the United States to provide for the duty-free entry of competition bobsleds and luges.”)

As a final example of the Carter White House’s continuing and colossal misreading of Congress, the President agreed to Vice President Mondale’s decision to sign the bill into law at a Democratic-Farmer-Labor party rally in Minneapolis, despite the fact that all of the state’s DFL legislators had voted against the bill on the grounds that it would increase shipping rates in the amply-served-by-inland-waterways Land of 10,000 Lakes and despite the fact that a schism within the DFL led to part of the crowd booing Carter when he shook hands with the leader of the other faction onstage. (The front-page headline of the Minneapolis Daily Star the following day was “DFLers boo Carter loudly when he supports Short.”)

And the White House staff felt that Adams had put Carter in a bad spot by insisting on the veto threat, further detracting from Carter’s popularity on Capitol Hill, so the White House refused to invite Adams, or anyone from DOT, to the signing ceremony. Adams and his staff took the FAA jet to Minneapolis and crashed the ceremony anyway, standing behind Carter as he signed the bill.[25] The bill became Public Law 95-502.

Implementation delays and the need for tax increases

The law provided that the only restrictions on the use of the Trust Fund moneys was that the money had to be available “as provided by appropriations Acts, for making construction and rehabilitation expenditures for navigation on the inland and intracoastal waterways of the United States…No amount may be appropriated out of the Trust Fund unless the law authorizing the expenditure for which the amount is appropriated explicitly provides that the appropriation is to be made out of the Trust Fund.”

This quickly proved problematic, as after the 1978 law was enacted, there came to be a complete breakdown between the White House and Congress over the authorization of water projects (under both Carter and Reagan). As such, no authorization bills for such projects were signed into law after the Trust Fund was created until the landmark Water Resources Development Act of 1986, after which the annual appropriations paragraph for the Corps’ General Construction account began to include, after the dollar amount of the appropriation, the codicil “…of which such sums as are necessary pursuant to Public Law 99-662 [WRDA 1986] shall be derived from the Inland Waterways Trust Fund…”[26] The was eventually changed to “of which such sums as are necessary to cover one-half of the costs of construction, replacement, rehabilitation, and expansion of inland waterways projects shall be derived from the Inland Waterways Trust Fund, except as otherwise specifically provided for in law…”

The tax levels feeding the Trust Fund were set in the 1978 Act at 4 cents per gallon in FY 1981, 6 cents per gallon in FY 1982 and 1983, 8 cents per gallon in FY 1984 and 1985, and 10 cents per gallon thereafter. This was amended by WRDA 1986 to increase the tax gradually to 20 cents per gallon between 1990 and 1994. That tax rate remained at 20 cents per gallon for 20 years.

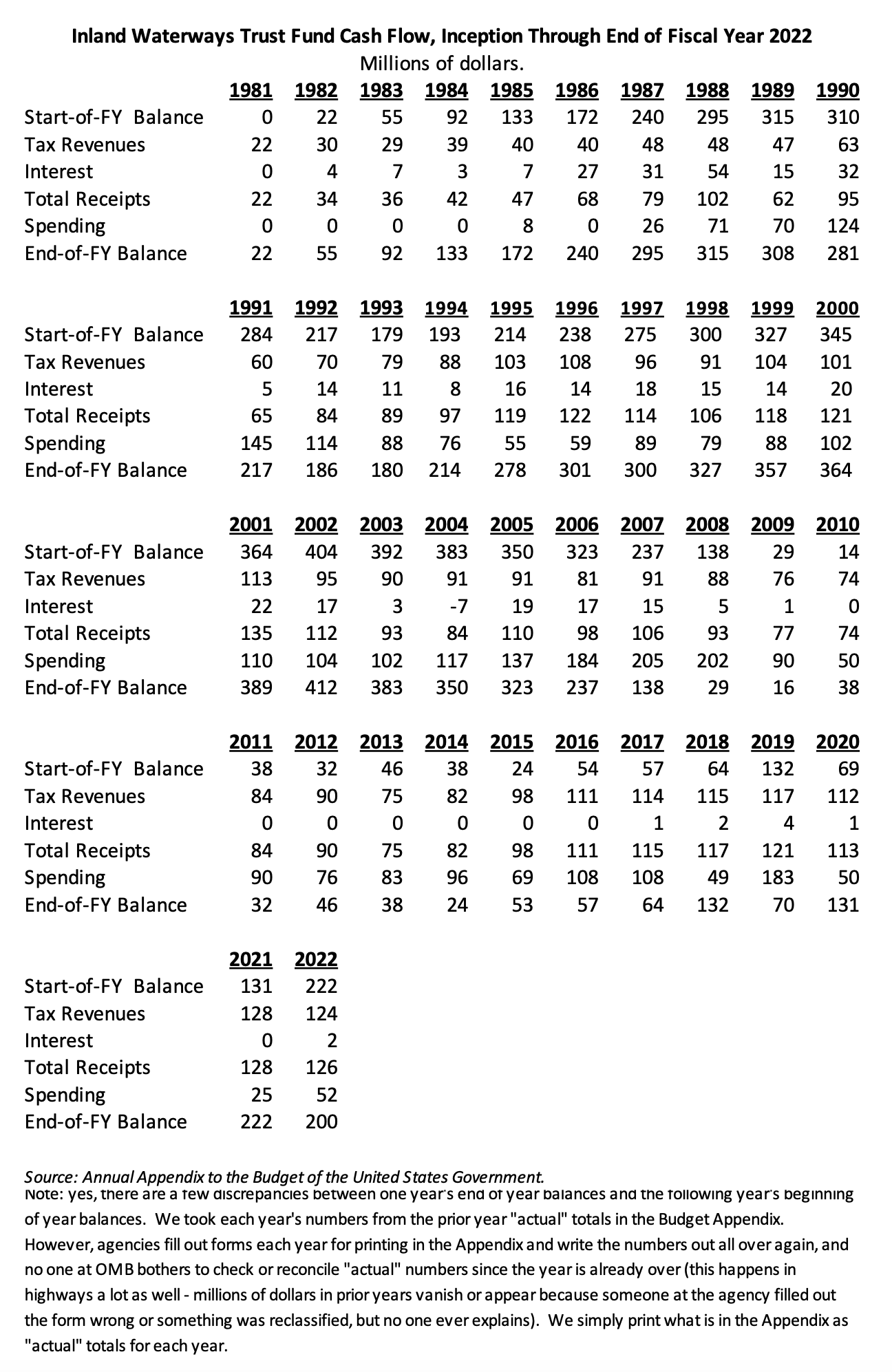

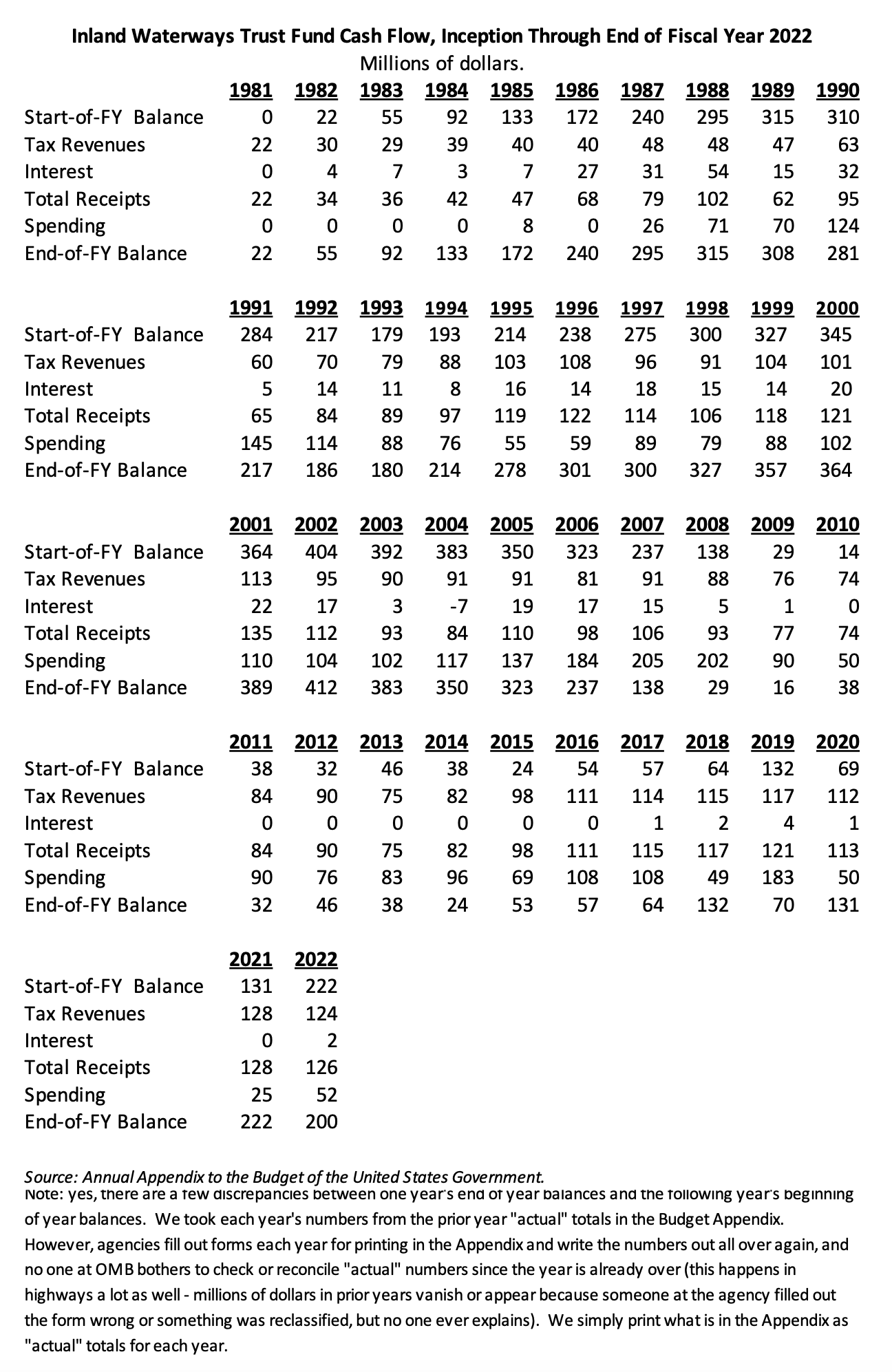

The 50-50 cost share for IWTF projects, and the 20 cent-per-gallon IWTF fuel tax rate, both had to change at around the same time, and for the same reason: the Olmsted Locks and Dam project on the Ohio River. Cost overruns on Olmsted, along with regular inland waterway work by the Corps, depleted the IWTF balance from $412 million at the end of 2002 to just $29 million at the end of 2008. Accordingly, starting in 2009, Congress began limiting annual appropriations from the IMTF to the approximate amount of yearly barge diesel tax receipts.

The unusual circumstances of the 2014 tax increase

This kept the IWTF solvent, but slowed down the pace of work. Accordingly, section 2006 of the 2014 WRDA law (P.L. 113-121) declared that, notwithstanding the 1986 50-50 cost share statute, the rest of the funding for the Olmsted project would be 85% general fund, 15% IWTF.

That law, enacted in June 2014, also commissioned the usual IWTF future revenue studies (sec. 2004) and stakeholder roundtable (sec. 2005) provisions to try and think up clever ways to raise more revenues for the IWTF, but before those had time to report, Congress wound up fixing the revenue problem in a very interesting way.

By 2014, instead of opposing a tax increase on the diesel fuel used to tow their barges, the barge industry was actively supporting a tax increase, with the Waterways Council urging its members all summer/fall to contact their legislators and ask them to “increase the Inland Waterways barge user fee” so that spending from the IWTF on locks and dams could, in turn, be increased.[27]

But the House of Representatives was controlled by the viscerally anti-tax-increase Republican Party. Even though the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, Dave Camp (R-MI), had included a 6 cent IWTF barge diesel tax increase in his giant tax reform bill in February 2014, that legislation was going nowhere fast. How to get a tax increase through the GOP-held House?

The answer could be taught in political science textbooks. Because the stakeholders who were going to be paying the increased tax were supportive of the tax increase, no one with a vested interest was out there campaigning against the increase. But that might not be enough, so the sponsors tied it to a very popular, unrelated bill using speed and obfuscation.

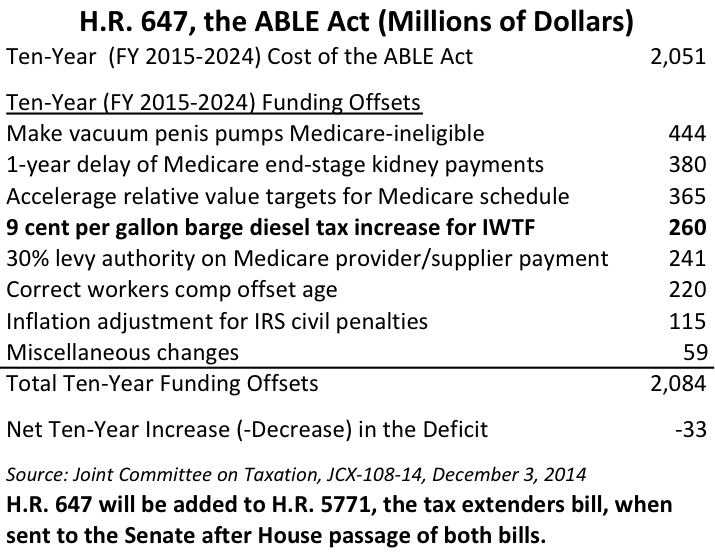

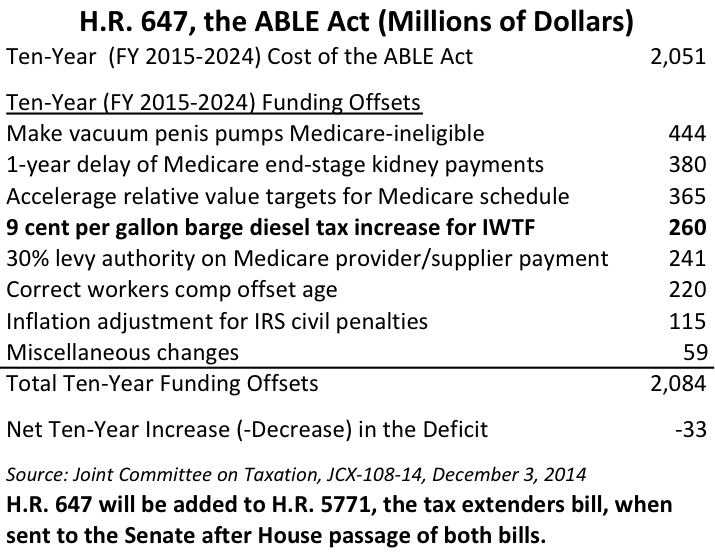

Popular vehicle. Throughout 2014, the Ways and Means Committee had also been considering completely unrelated legislation to allow parents of disabled children to establish tax-deferred savings accounts (similar to “529” college funds) to support the children after they turned 18. This bill, the “ABLE Act,” was estimated to cost the Treasury $2.05 billion in lost tax revenue over ten years, and under the House GOP procedures at the time, some combination of “pay-fors” had to be found to offset that $2.05 billion revenue loss before the otherwise-popular bill (very, very popular – 380 House cosponsors out of total membership of 435) could get a vote in the House.

Speed. As the Congress was trying to finish up its work, ABLE Act sponsors released their text of the bill with its never-before-seen “pay-fors” at 8:15 p.m. on December 1, 2014, on the House Rules Committee website. One of those, in section 205, was a 9 cent-per-gallon increase in the IWTF barge diesel fuel tax rate.

The House brought up the ABLE Act under an expedited procedure with just one up-or-down vote (no amendments), and the roll call started at 4:11 p.m. on December 3, just 44 hours after the existence of the barge diesel tax was made public.

Obfuscation. Here is the list of the ABLE Act’s pay-fors, estimated to raise $2.08 billion in revenue, offsetting the bill’s $2.05 billion cost. See if you, dear reader, can guess which one of the tax increases got all the media attention (to the extent that the tax increases got any media attention at all):

If you guessed “the penis pumps,” you are correct. See Washington Post, Slate, and The Atlantic headlines from that week. The bill also raced through the Senate as part of a larger year-end tax extenders bill, and in neither chamber was the barge diesel tax mentioned. The rate went up to 29 cents per gallon, increasing annual IWTF receipts from around $80 million per year to around $120 million per year.

The cost of megaprojects being funded out of the IWTF has still increased beyond the ability of the Trust Fund to handle it, so just as they did for Olmsted, Congress later lowered the IWTF share of the next megaproject, Chickamauga Locks and Dam, from 50 percent to 15 percent.

From its inception (effective in fiscal 1981) through the end of fiscal 1922, the IWTF has received $3.446 billion in tax receipts and paid $3.483 billion in outlays (the other $20 million being the result of interest earned on balances).

[1] T.R. Reid. Congressional Odyssey: The Saga of a Senate Bill. New York: W.H. Freeman 1980, pp. 10-12.

[2] Specific volume and page citations can be found in Jeff Davis, “Transportation User Charge Proposals in the President’s Budget, 1941 to Present,” Eno Center for Transportation, July 18, 2023, at https://enotrans.org/article/transportation-user-charge-proposals-in-the-presidents-budget-1941-to-present/

[3] Allen Drury. Advise and Consent. Garden City, New York: Doubleday 1959 pp. 144-145.

[4] Reid p. 13.

[5] Office of Management and Budget. Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 1978. Washington: GPO 1977 pp. 240-241.

[6] Reid pp. 49-52.

[7] Jimmy Carter, Water Resource Projects Message to the Congress. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/241932

[8] Jimmy Carter, Water Resource Projects – Letter to Members of Congress. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/243124

[9] Jimmy Carter, Water Resource Projects – Statement Announcing Administration Decisions Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/243376

[10] Letter from Brock Adams to Jimmy Carter, May 9, 1977 and memo from Stu Eizenstat to Jimmy Carter, May 11, 1977. Located in folder “5/11/77[4],” container 20, series “Presidential Files,” Office of the Staff Secretary collection, Carter Library. Online at https://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/pdf_documents/digital_library/sso/148878/20/SSO_148878_020_03.pdf

[11] Letter reprinted in Congressional Record (bound edition), June 22, 1977, p. 20365.

[12] Jimmy Carter, The President’s News Conference Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/245038

[13] Congressional Record (bound edition), June 22, 1977, pages 20397 and 20415.

[14] Reid pp. 69-75.

[15] Reid p. 77.

[16] See U.S. Congress. House of Representatives. Committee on Public Works and Transportation. Waterways User Charges. Washington: GPO 1977.

[17] Congressional Record (bound edition), October 13, 1977 p. 33646.

[18] Reid pp. 91-92.

[19] Reid pp. 93-94.

[20] Congressional Record (bound edition), May 1, 1978, pp. 11906-11910.

[21] Congressional Record (bound edition), May 3, 1978, pp. 12379-12380.

[22] Jimmy Carter, The President’s News Conference Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/245038

[23] Reid p. 112.

[24] Congressional Record (bound edition), October 13, 1978, pp. 36965-36966 (the actual vote was on a motion to suspend the rules and adopt H. Res. 1432, a resolution deeming the House to have agreed to the Senate amendments to H.R. 8533).

[25] Author’s personal email exchange with Mortimer Downey, September 7, 2009.

[26] Public Law 100-202.

[27] Waterways Council, Inc. website, archived on August 29, 2014 at https://web.archive.org/web/20140829085201/http://waterwayscouncil.org/