This article is a part of our series From Lighthouses to Electric Chargers: A Presidential Series on Transportation Innovations

The seventh president of the U.S. and the first from west of the Appalachians, Andrew Jackson served from 1829 to 1837. Born in Waxhaw, South Carolina, Jackson endured a challenging childhood, losing all of his nuclear family by the age of 14 and receiving a very sporadic education. In his teenage years, he began studying law, and after moving between the Carolinas a few times, he eventually made his way west to what would become Tennessee and began practicing as an attorney.

It was in Tennessee that Andrew Jackson began to build his wealth and reputation. In one of his first elected positions, he was selected as a delegate to the Tennessee Constitutional Convention in 1795 before Tennessee became a state the following year. Jackson held many political positions in his life, serving as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, a member of the U.S. Senate, a commissioned major general of the Tennessee militia, a circuit-riding judge of the Superior Court of Tennessee, and the appointed governor of the Florida territory.

The road to the presidency was not a smooth one and was paved on the idea of a government representative of all voters (which at the time meant most white men over the age of 21), rather than solely the political and economic elite. It was in this window that the concept of Jacksonian Democracy emerged, which led to the merging of some Jeffersonian Republicans and Democratic-Republicans into a political party known as the “Democrats.” The opposing “Whig” party was formed by former Democrats, National Republicans, and others.

In his first run for president, he lost to John Quincy Adams in 1824. (See previous article in this series.) Jackson’s bid for the presidency displayed many of the trends and characteristics of a populist candidate, and his loss later impacted some of his stances and policies as president.

The rematch between Jackson and Adams in 1828 was a highly contentious election cycle, marked by vicious and often personal attacks by each side. The narrative of a stolen election in 1824 was relied upon heavily by Jackson to create division and distrust between the common man and government – a storyline which carries some similarities to a recent election cycle.

Following former President Donald Trump’s 2016 victory over Hillary Clinton, the former mayor of New York City and Trump campaign adviser, Rudy Giuliani, drawing a comparison between the 1828 and 2016 elections said, “This is like Andrew Jackson’s victory. This is the people beating the establishment. And that’s how [Donald Trump] posited right from the beginning, the people are rising up against a government they find to be dysfunctional. And yes, it’s a defeat for the Democrats, but this is a defeat for some Republicans too.”

The appeals to the common man, the erosion of trust toward government, and other populist themes carried strongly through both presidencies. For Jackson, his presidential policies at times carried conflicting stances, and his policies were sometimes considered short-sighted, neglecting long-term implications of actions.

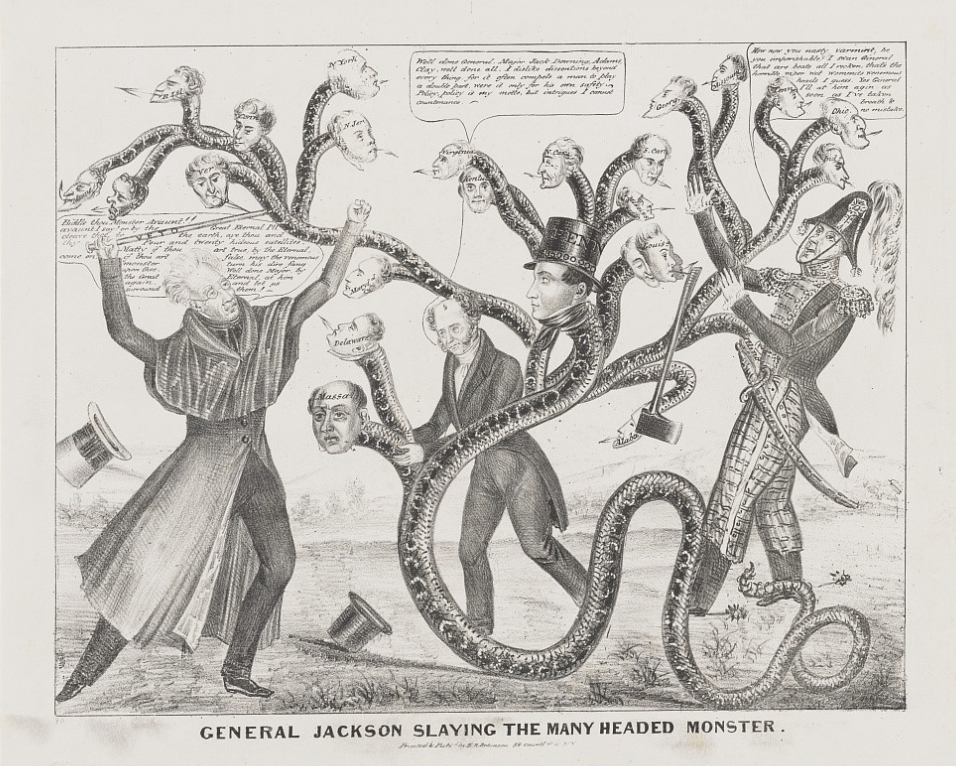

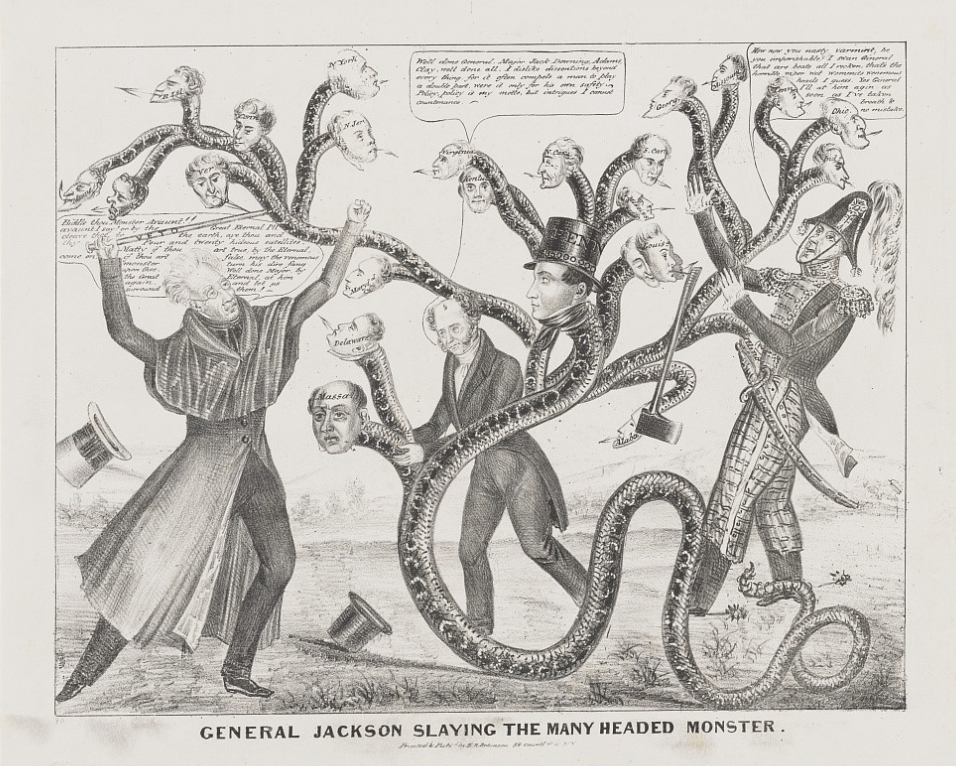

Source: Library of Congress

For example, although Jackson vehemently opposed the “American System,” a philosophy which included using federal funds for internal improvements, his 1831 presidential address lauded the many internal improvements that had been made in recent decades. He boasted how farmers were able to get their crops to market and manufacturers could ship their goods around the world because of the “works of internal improvement, which are extending with unprecedented rapidity.” He noted how the speed of mail “is regularly increased and whose routes are every year extended: and communication between distant cities that previously “required weeks to accomplish, is now effected in a few days.”

While a staunch constitutionalist, firmly rooted in his opposition toward using federal funding for state projects, Jackson’s disdain toward the “American System” was also influenced by his distaste for the philosophy’s creator – Henry Clay. During the election of 1824, then-House Speaker Clay mobilized the support needed to elect John Quincy Adams to the presidency. Clay went on to become Adams’ Secretary of State with John Calhoun serving as the vice president. Jackson never forgave or forgot this apparent quid pro quo, and in the final days of his second term, when asked if he had any regrets, he replied, “I regret that I was unable to shoot Henry Clay or to hang John C. Calhoun.”

Jackson applauded internal improvements for bolstering trade by taking advantage of the nation’s “extensive coast, indented by capacious bays, noble rivers, inland seas” along with a “country productive of every material for ship building and every commodity for gainful commerce, and filled with a population active, intelligent, well-informed, and fearless of danger.” He noted how rail roads and steam power were making extreme parts of the country accessible, quelling the concerns of some that the vast size of the country made it ungovernable.

Similar to many of Jackson’s other policies, his stance toward internal improvements ebbed and flowed. As a senator, he consistently voted in favor of internal improvement projects yet frequently conveyed concerns that congressionally authorized internal improvements were not permitted by the constitution and the responsibility of certain projects should fall to states. Paired with his strong aversion to debt, Jackson’s position on these improvements was at times ambiguous.

When Jackson first assumed the presidency, he saw the need for some internal improvements, particularly in transportation, due to mobility challenges faced in the War of 1812. He viewed federally funded internal improvements as highly important if they served the nation as a whole and contributed to military and economic strength, but his earlier hesitancies toward internal improvement projects and opposition to debt, strengthened in his presidential years. While the above address from 1831 still lauded internal improvements, these projects began to face more intense scrutiny based on whether they served only a state/local region or if they were actually an improvement for national benefit. While rivers and harbors carried more of a perception of national benefit due to natural geography (rivers often touch multiple states), Jackson was resistant to funding roads and canals.

Jackson’s stance was clarified with a series of road project vetoes beginning with a veto of the Maysville Road Project in 1830 on the basis that this was a local rather than regional project. The project, not so coincidentally in the home state of and a project supported by his political rival Henry Clay, would have connected Lexington, Kentucky to Maysville, Kentucky. Following this veto, Jackson rejected other similar projects, but due to the timing, and the potentially personal motivation, it remains one of the more well-known vetoes in U.S. history.

By the end of Jackson’s presidency, he fulfilled his promise of eliminating the national debt he had inherited from his predecessors. In 1835 and 1836, the U.S. was debt free for the first and last time in its history.

This article is a part of our series From Lighthouses to Electric Chargers: A Presidential Series on Transportation Innovations