This week, I testified before the House Highways and Transit Subcommittee at its hearing, “Running on Empty: The Highway Trust Fund.” My written testimony first explained how and why the Trust Fund went broke, and suggested three questions that Congress should answer when trying to find ways to fix it. The “Three Questions” part is reproduced below. (These are my own views, not official positions taken by the Eno Center.)

WHAT TO DO NOW

Policymakers need to ask and answer three questions, in order – the first philosophical, the second strategic, and the third tactical.

- Philosophical question – should the federal government retain the user-pay system for surface transportation?

Although the user-pay paradigm served U.S. surface transportation well in the past, and continues to finance the world’s safest aviation system, most of our OECD peer nations no longer use a centralized user-pay fund for their national surface transportation programs. The U.K. abandoned user-pay for roads in 1937 (though they been talking about bringing it back lately). The Eno Center produced a report in 2014 called How We Pay for Transportation: The Life or Death of the Highway Trust Fund that analyzed how several peer nations fund their road networks, though some of the information may now be outdated.

In their new book The Drive for Dollars: How Fiscal Politics Shaped Urban Freeways and Transformed American Cities (Oxford U. Press, 2023), Professors Brian Taylor, Eric Morris, and Jeffrey Brown credit federal and state user-pay road funds, reliant primarily on gasoline taxes, with the tremendous economic productivity and safety gains that stem from today’s well-developed freeway system. But they also note that because the federal and state highway bureaus were so well funded, and cities were not, the user-pay model is also responsible for urban freeways being built by state engineers over the objections of city planners in many cities, with all the problems that caused.

Right now, we have the worst of both worlds. We are pretending that the Highway Trust Fund is still solvent on a user-pay, user-benefit basis, and continue to give Trust Fund programs a privileged place in the budget process. But the reality is that the Trust Fund is only projected to be 82 percent self-sufficient this year (fiscal 2024), with that solvency dipping rapidly until the Trust Fund is only 60 percent self-sufficient in the last year of the IIJA (fiscal 2026), and dipping below 50 percent self-sufficient in 2031.

That bears repeating – at current tax rates and IIJA spending levels, CBO forecasts that every other dollar being outlaid by the Trust Fund will be from a general fund transfer or other non-user source in just eight years.

From a truth-in-budgeting perspective, the choice seems clear: it’s time to either mend, or end, the Highway Trust Fund. Either cut spending and/or increase user revenues to the point that they meet once again, or abolish the Trust Fund, devote the five existing user taxes back to the General Fund, and have highway, mass transit, and highway and motor carrier safety funding fight it out with all other programs through the budget process.

Either of those outcomes would be more honest than maintaining a purported user-pay trust fund by simply printing dollars as needed to keep the Trust Fund afloat, depositing those dollars as needed into the Trust Fund, and using the “intragovernmental transfer” budget loophole to avoid having to budget for the bailouts.

Neither option would be easy. (The option for a relatively painless off-ramp from this situation passed us by circa 2010 or 2011.) Real revenue increases are always politically painful, and spending cuts of the magnitude required here would also be severely painful. But retaining the user-pay Trust Fund option would allow this committee to retain its privileged place in the transportation decision-making process.

Before 2021, I would have told you that the “abolish the Trust Fund” scenario would leave the authorizing committees out of the funding process and put the Appropriations Committees in complete control. But in 2021 and 2022, Congress used the budget reconciliation process to order this committee and its Senate counterparts, among others, to produce general fund mandatory budget authority for things like mass transit, Amtrak, airports, and new Federal Highway Administration grant programs.

It would be complicated, but a budget process could be established to allow this committee and the Appropriations Committee to split duties for funding these programs out of general revenues. However, given the difficulty of getting eight-way unanimity between House and Senate Budget, Appropriations, tax-writing, and transportation policy committees to establish such a process, draconian spending cuts and/or huge tax increases might be an easier political lift.

- Strategic question – if the federal government keeps the user-pay system, what share of surface transportation programs should users pay, and which specific programs should users pay for, versus general taxpayers?

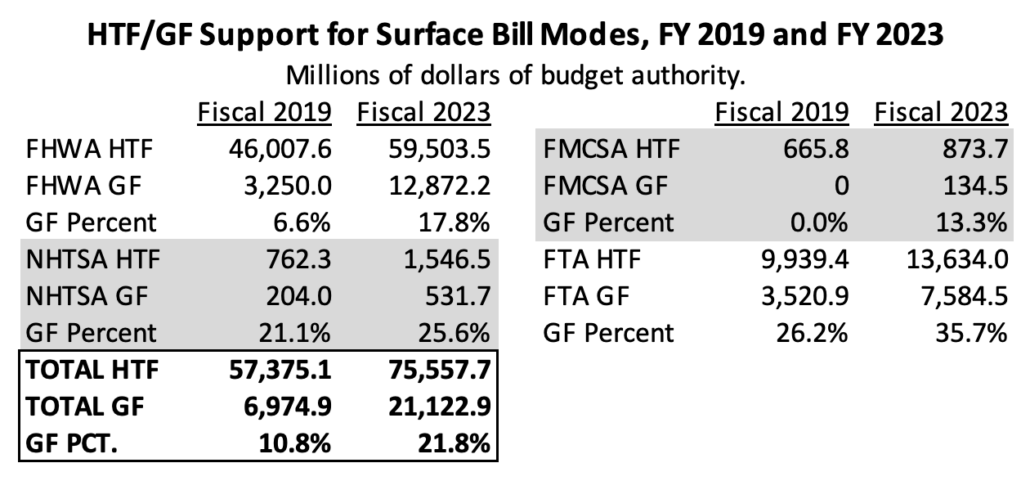

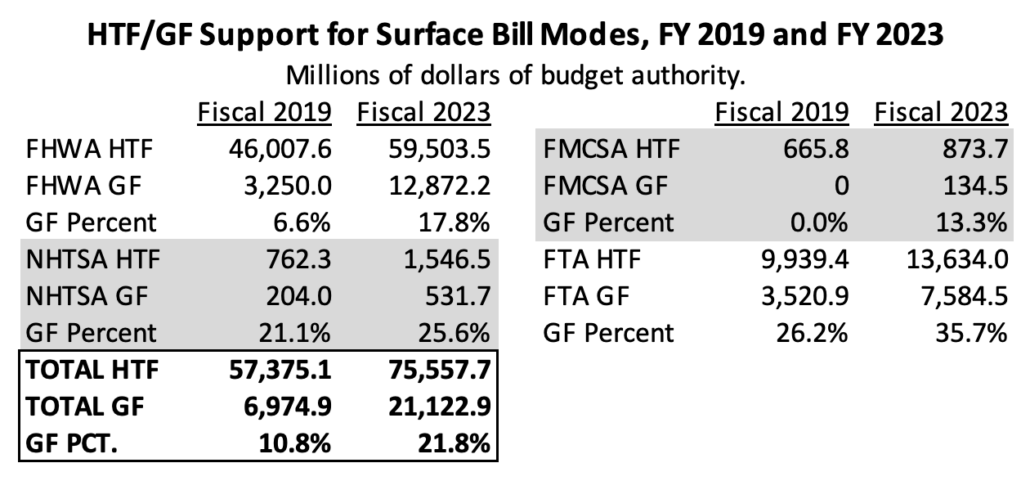

The 2018 budget caps deal and the IIJA have combined to increase significantly the annual General Fund support for the four modal administrations traditionally supported by this subcommittee. In the last pre-COVID fiscal year, the General Fund provided 11 percent of the total funding for the highway, transit, and safety administrations. In the just-ended fiscal year, the General Fund provided 22 percent of a greatly increased total funding level.

The decisions as to which programs to fund from the Trust Fund and which to fund from the General Fund have been made on a somewhat ad hoc basis over the years, and the decisions made by the IIJA were made without this committee’s input. If Congress decides to retain a solvent user-pay Trust Fund to support some surface transportation programs, which ones are more appropriately supported by highway users and which by general revenues?

If Congress were to examine these programs from the ground up and ask, which kinds should be supported by the dedicated user-pay revenue stream and which should be supported by general revenues, some decision options include:

- Capital programs vs operations and maintenance. Across most modes of infrastructure, the tradition is for the federal government to concentrate on capital funding, while state and local government partners focus on operational and maintenance funding. For example, the Airport and Airway Trust Fund is governed by statues that give the FAA’s capital programs and airport grants priority over FAA operations for Trust Fund dollars. If Congress were to act to split up current Trust Fund programs and give a portion to general revenues, they might use this principle as a guide.

- Long-term vs short-term planning horizons. It certainly makes sense to reserve scarce user-pay funding secured with a long-term revenue stream to fund the projects that take the longest to build or which have the longest planning horizons. Consider, then, if Congress continues to fund mass transit from the Trust Fund, how incongruous it is that the Capital Investment Grant (CIG) program funds all the big new transit system extensions that take the longest to plan and build, but that is the only FTA program authorized to be reliant solely on annual appropriations. This makes a mockery of the “full funding grant agreements” signed by FTA and project sponsors, which are replete with boilerplate language reminding people that a FFGA is not a contract and does not actually require the federal government to provide any money, ever. These programs were formerly funded out of the Trust Fund in recognition that multi-year funding was preferable for projects that take six to ten years to construct. On the highway side, Congress could likewise choose to fund the longest lead-time projects from the Trust Fund while leaving routine resurfacing and other quickly completed projects from general revenues.

- National vs state/regional. Support from the general fund traditionally goes to programs for the general welfare. User-pay programs are generally biased towards going where the users are. An honestly budget general fund component of surface transportation funding in the future should be isolated from any mention of, or connection to, how much money a state pays in user taxes. The donor-donee debate (currently obsolete because of Trust Fund solvency – see Appendix A to this testimony) must never apply to general fund programs.

- Relative benefit to user-taxpayer. The other half of the user-pay model has always been user-benefit (the user pays for programs that give him or her direct benefit, and in this instance, the user of the roads pays for construction and upkeep of those roads). Using user fees to pay for programs that only give indirect benefit to users, like mass transit (at best, it decreases the congestion faced by road users to some degree) has always been controversial. A fundamental redesign of the system could address that.

When taking current Trust Fund programs out of the Trust Fund, Congress could keep those programs federal and transfer them to the General Fund, or they could shift the burden to state or local governments. In recent decades, some in Congress have felt that, post-Interstate, there was no more need for a large federal transportation program, and have sought to “devolve” most of that duty to the states, abolishing federal programs while lowering federal excise taxes at the same time.

Setting aside the philosophical and policy aspects of devolution, the fundamental problem has always been math. Highway Trust Fund programs are among the slowest-spending in government. If we had shut down the entire Trust Fund, permanently, 18 days ago at the start of the fiscal year, and put a permanent end to all its programs (no new projects, contracts, or grants, ever, and fire everyone), CBO says that the Trust Fund would still have to pay $130 billion over the next decade just to pay off all of the contracts and grants that were signed prior to October 1, 2023.

At a current user tax yield of around $43 billion per year, that means that you would have to maintain the current federal taxes at their current rates for three full years after you devolve all the programs to the states. But the states, having balanced budget requirements, would have to raise their own taxes immediately to take over their share of the programs, leading to three-year transition period of double taxation, which would certainly be noticed by motorists.

(The same math also applies to any effort to downsize Trust Fund programs to make them fit within current tax rates – you have to cut the rate of new contracts being signed several years before you see significant reductions in the cash going out the door.)

The most important thing is that, in any future system where Trust Fund user taxes and General Fund resources both pay for surface transportation, the General Fund money must be appropriated outside of, and in addition to, the Highway Trust Fund instead of being transferred into the Trust Fund and making the user-pay imbalance worse.

At the end of this process, the goal is to get to a number – the amount of money that needs to be received in user taxes or fees from system users each year in order to pay for the Trust Fund programs that remain at the end of this reevaluation. The third question can then be asked and answered and those user receipts raised. (Alternatively, if one answers the third question before the second question, the Trust Fund revenue number would then govern the decisions made in answer to the second question.)

- Tactical question – if the federal government keeps the user-pay system, and if the amount we want to raise from system users exceeds the forecast of proceeds from current tax rates, how should we raise user revenues in the future?

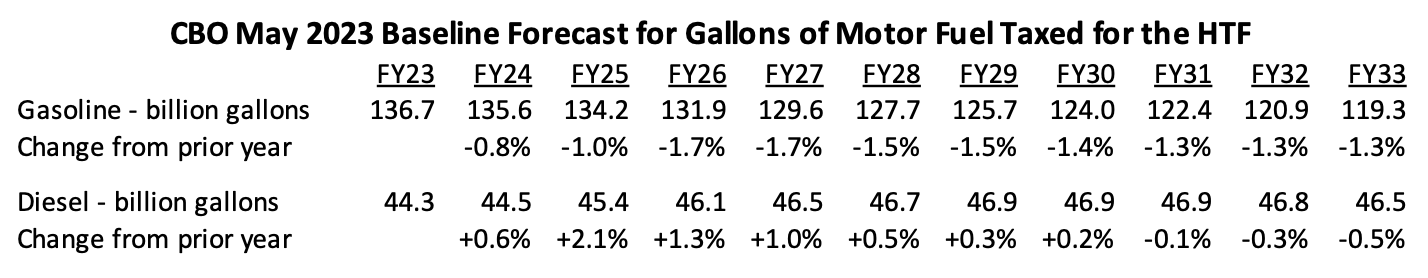

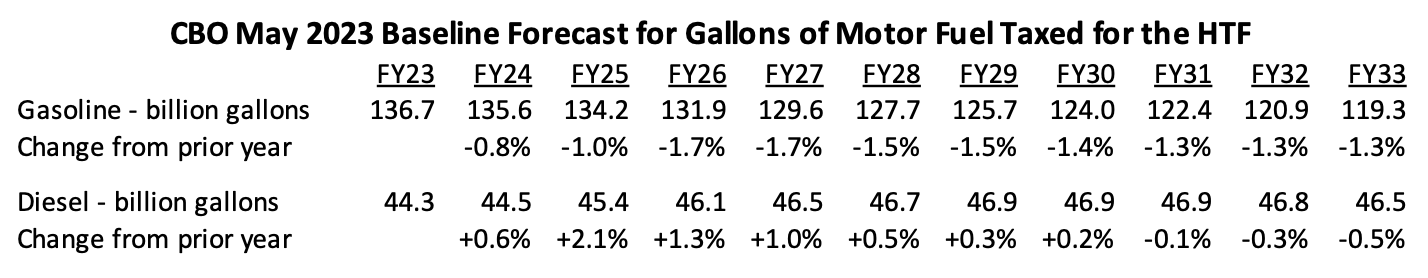

Current projections are for the number of gasoline taxed for the Trust Fund to steadily decline over the next decade at an average rate of 1.4 percent per year. Diesel fuel receipts should fare a little better because increased freight trucking volume will offset more fuel-efficient trucks to some degree.

These rates of decline are not yet to the point where an increase in the motor fuels tax rates could capture significant revenue, though projections indicate that returns will diminish rapidly in the 15 to 30-year timeframe. (There are, of course, severe political problems with increasing motor fuel taxes, on both sides of the aisle.)

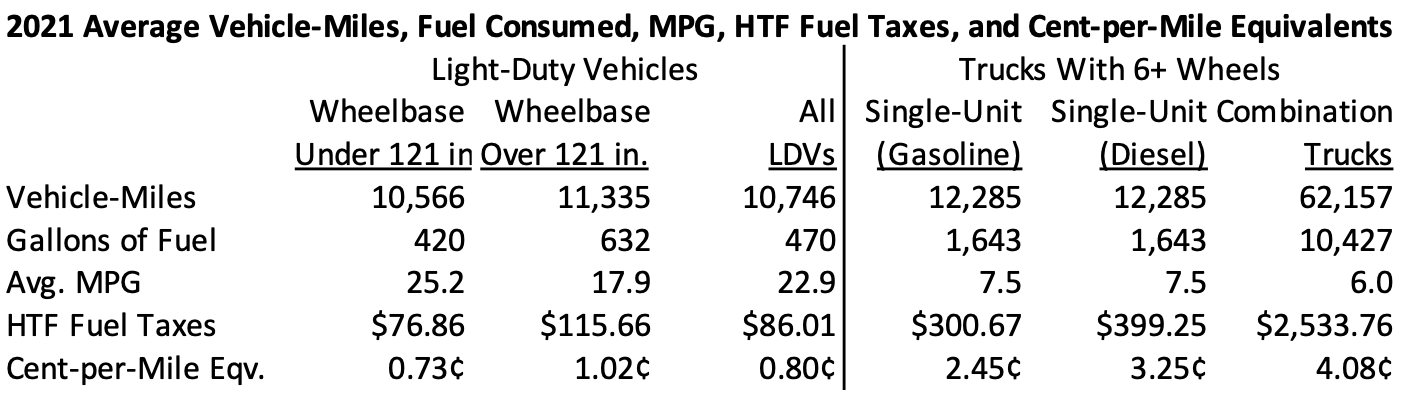

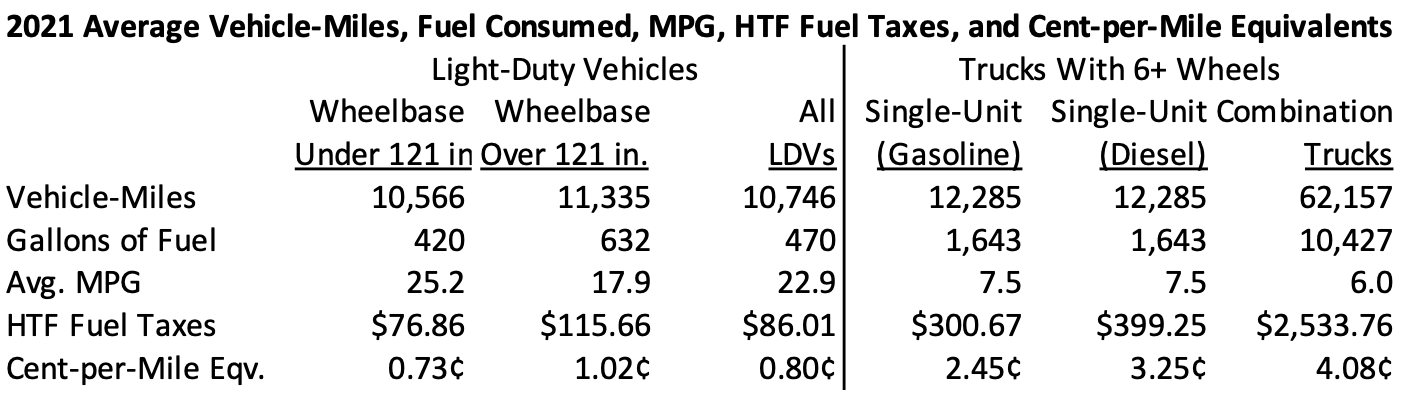

Motor fuel taxes have always been a proxy for vehicle miles traveled. It is a simple matter to take the latest FHWA data on average miles traveled and fuel efficiency, cross it with current federal fuel tax rates, and deduce how many cents per mile that different types of vehicle are currently paying into the Highway Trust Fund. (The year in question being 2021, the average distance numbers may still be slightly COVID-depressed.)

Data source: FHWA Table VM-1 in Highway Statistics 2021.

The most-discussed idea for retaining the user-pay paradigm while transitioning away from motor fuel taxes is some sort of fee charging individual vehicles for their miles-traveled, called a VMT fee (alternately called a mileage-based user fee (MBUF), or a road user charge (RUC)).

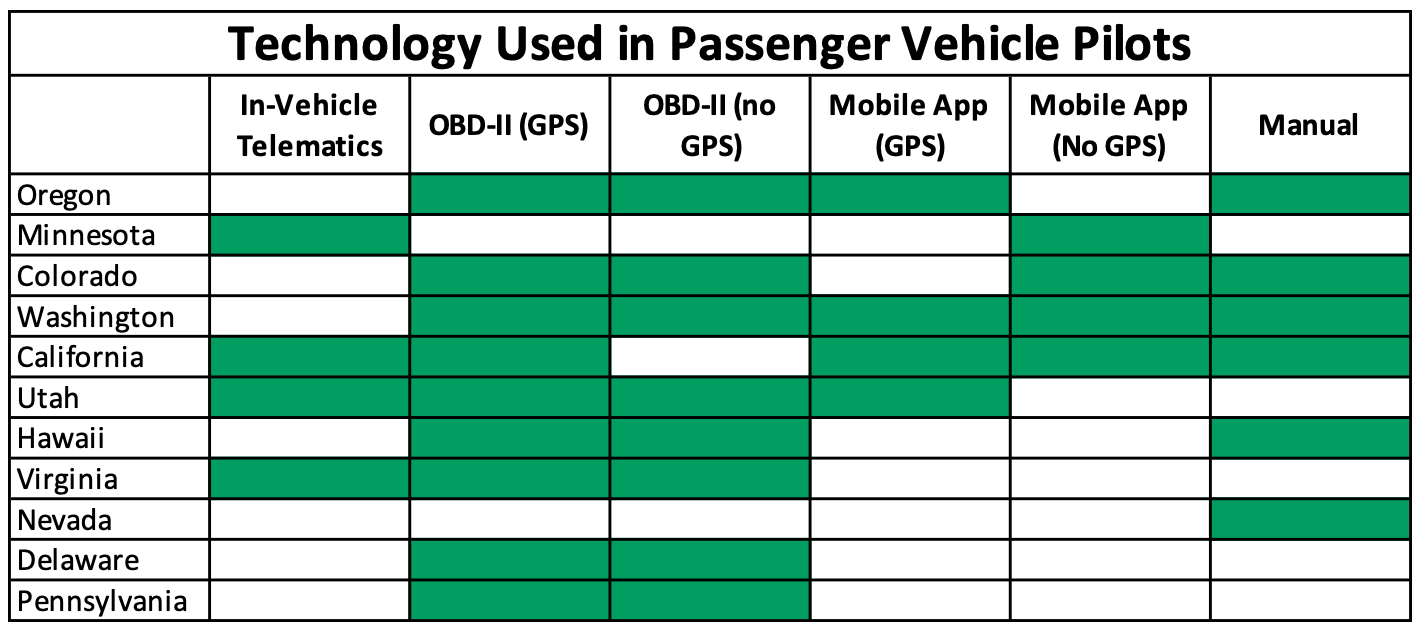

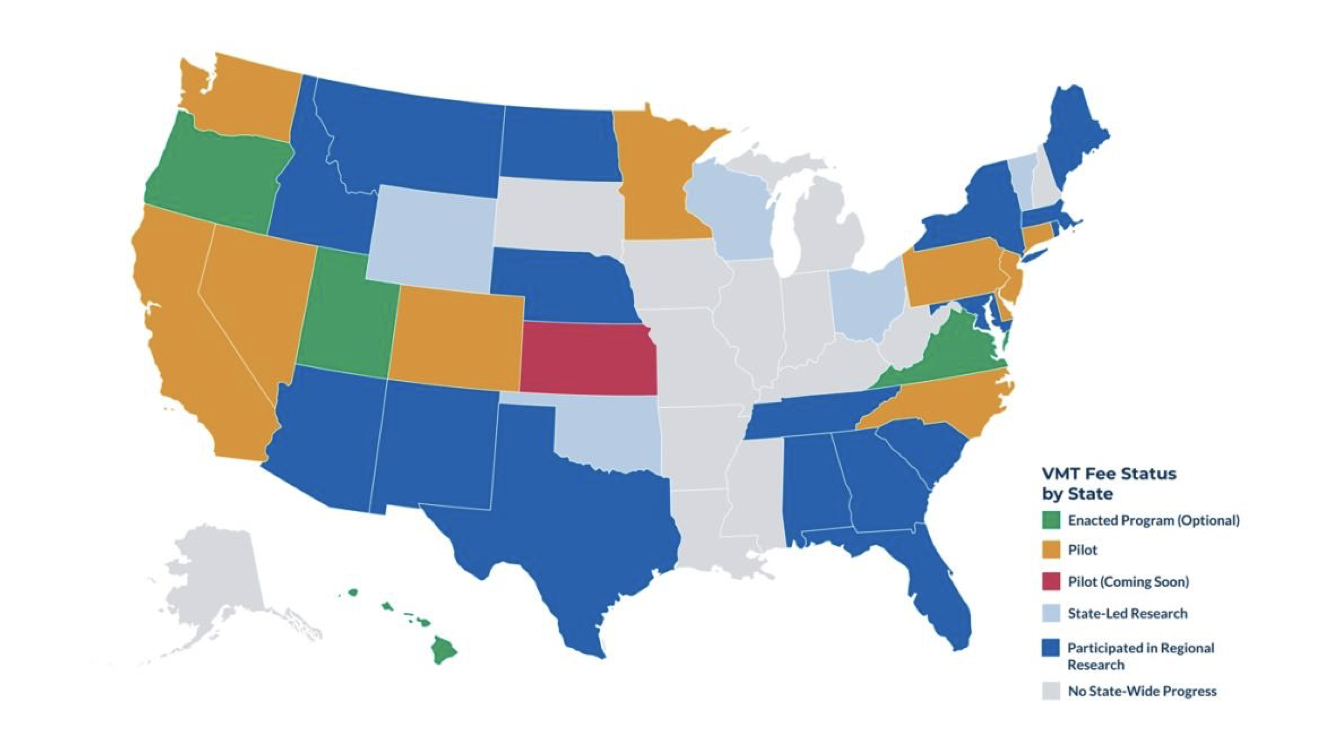

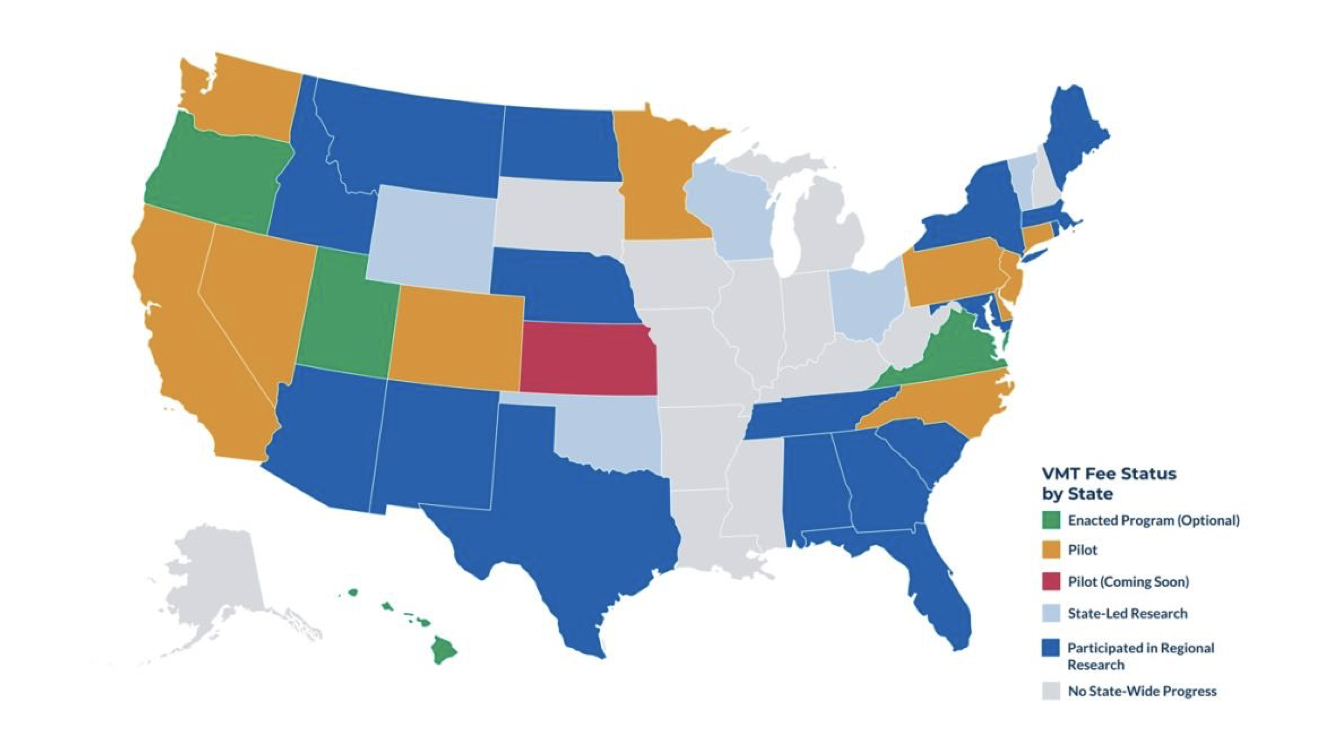

As [Oregon DOT] Director Strickler has mentioned, there has already been significant interest in this idea at the state level, with Oregon taking the lead in testing back in 2001 and now having its own permanent program where motorists can choose to pay by the mile instead of by the gallon. Hawaii, Utah, and Virginia now also have permanent VMT fee programs, while several other states are currently testing pilot programs or conducting research.

At the federal level, the IIJA mandates that DOT and Treasury must carry out a pilot project testing a VMT fee in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, and provides $50 million for that purpose. The pilot program must include both personal vehicles and commercial trucks, and volunteers will have their mileage fees deposited in the Highway Trust Fund. The Eno Center recently issued a report, Driving Change: Advice for the National VMT-Fee Pilot, which reviews the various state (and international) efforts and suggests some best practices for DOT to follow in establishing the program.

At the federal level, the IIJA mandates that DOT and Treasury must carry out a pilot project testing a VMT fee in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, and provides $50 million for that purpose. The pilot program must include both personal vehicles and commercial trucks, and volunteers will have their mileage fees deposited in the Highway Trust Fund. The Eno Center recently issued a report, Driving Change: Advice for the National VMT-Fee Pilot, which reviews the various state (and international) efforts and suggests some best practices for DOT to follow in establishing the program.

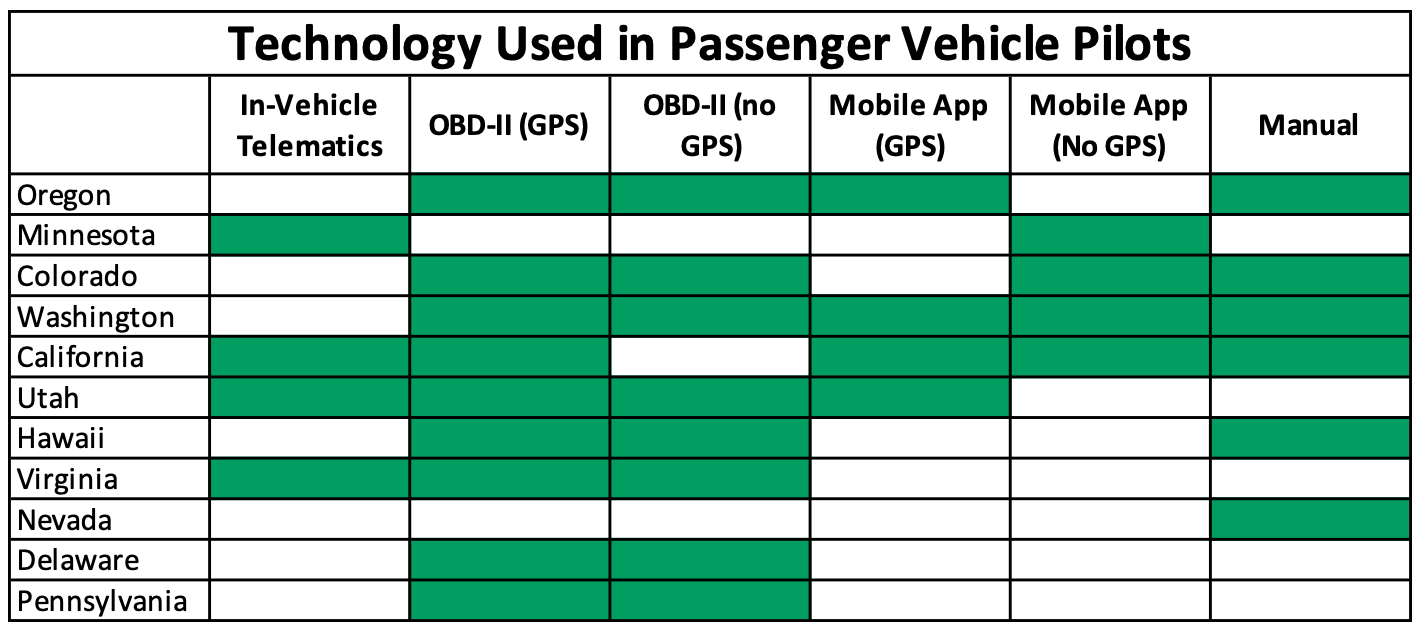

States have given DOT a wealth of options from which to choose – having miles measured by vehicle telematics; by on-board diagnostic (OBD) port boxes that can either have GPS info or just mileage; by an app on the driver’s cell phone that can either have GPS or just mileage; or by periodic odometer readings. And they have multiple options for reporting the miles and paying the fees, including at the pump, or with state income taxes, or other kinds of periodic filings.

However, DOT is almost two full years behind schedule in establishing the pilot program, raising questions about whether or not information from the program will be available to Congress when it comes time for the IIJA to be reauthorized in 2026.

A VMT fee is attractive for several reasons. It its most basic form, it records how many miles were driven, and that can be combined with vehicle axle-weight to be a good measure of wear-and-tear incurred on roads. If measured by GPS, it could also allow proper cost allocation between federal, state, and local roads. And if the system has interactive electronics in the car, it could be combined with local options such as tolls, congestion or cordon pricing, and dynamic time-of-day pricing. The fee structure could also take into account personal considerations and give lower rates to low-income drivers or to rural drivers.

However, any transition from motor fuel taxes to a similarly broad-based user-tax system must recon with collection costs. From a federal level, motor fuel taxes are fantastically easy to administer, since they are levied at the refinery or wholesale tank farm. CBO has estimated that there are only 1,300 or so points of collection, and it doesn’t take much IRS manpower to collect estimated taxes twice monthly, process quarterly returns, and do audits and make corrections, all to bring in around $35 billion per year in federal receipts.

Retaining user-pay but switching from fuels to cars or drivers involves going from about 1,300 points of collection to either drivers (233 million in 2021) or vehicles (278 million in 2021). Either way, this is around a 200,000-fold increase in the number of points of collection. In addition, many people drive cars who don’t file income taxes, and don’t have bank accounts, and may even lack smartphones, making compliance difficult. Congress has yet to hear from the IRS as to how much the administrative cost would be to run such a program.

In the interim, there are other sources of user revenue that could be addressed. There has been much discussion of electric vehicles (EVs), which currently pay nothing into the Highway Trust Fund yet use federal-aid roads just like taxpaying, fuel-burning vehicles.

A federal registration charge for EVs has the same problem that all registration fees have – a car that drives 2,500 miles per year pays the same as a car that drives 25,000 miles per year, even though one has ten times the road use as the other. A mileage tax on EVs, if set at the same approximate level that an internal combustion vehicle of the same axle-weight pays per mile in fuel taxes, would be the fairest outcome but has the same implementation problems as the VMT fee listed above.

Senator Cornyn has proposed a tax on EV batteries dedicated to the Trust Fund. There have been other proposals to tax the electricity used to charge EV and dedicate those proceeds to the Trust Fund, which is easy enough at commercial charging stations, but is currently somewhere between very expensive and impossible for the majority of charging, which currently takes place in a private home.

All methods of raising Trust Fund money from EVs, however, run up against the sheer incongruity that is the left arm of Uncle Sam paying people $7,500 up front to buy new EVs (through the IRA tax credits) while the right arm of Uncle Sam takes a hundred bucks or so out of that $7,500 back each year for road user charges into the Highway Trust Fund.

A July 2023 study from the MIT Mobility Initiative and the JTL Transit Lab suggests that any motor fuel tax replacement revenue source be evaluated through two “lenses”: “a performance lens and an efficiency lens. The performance lens considers (i) ease of administration, (ii) resistance to easy evasion, (iii) stability over time, and (iv) fairness. The efficiency lens considers how well or poorly certain revenue alternatives address key negative externalities of vehicular mobility: (i) traffic congestion, (ii) road wear and tear, (iii) safety and (iv) emissions.”

The summary tables 6 and 7 of that report are too long to reprint here, but variable VMT fees at the regional/national level, and variable tolls (called, for some reason, Road User Charges in the MIT/JTL report even though that is very confusing to the RUC Coalition people who use that name for their VMT fee) at a local level, score best on both the performance assessment and the efficiency assessment.

The IIJA directed the Federal Highway Administration to conduct the first highway cost allocation study since 1997. When complete, the information from that study could be used to set an axle-weight based vehicle fee in such a way that it fairly captures the costs incurred by various kinds of vehicles.

But all potential new revenue sources run up against the same problem: replacement level is not enough in an insolvent fund. Current tax rates only bring in $43 billion per year in receipts. Trust Fund spending was around $60 billion in the fiscal year that finished last month and will be around $75 billion in 2026. Simply replacing current Trust Fund revenue levels will not be nearly enough unless you also cut Trust Fund spending significantly. Dollars going out have to equal dollars going in.

At the federal level, the IIJA mandates that DOT and Treasury must carry out a pilot project testing a VMT fee in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, and provides $50 million for that purpose. The pilot program must include both personal vehicles and commercial trucks, and volunteers will have their mileage fees deposited in the Highway Trust Fund. The Eno Center recently issued a report,

At the federal level, the IIJA mandates that DOT and Treasury must carry out a pilot project testing a VMT fee in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, and provides $50 million for that purpose. The pilot program must include both personal vehicles and commercial trucks, and volunteers will have their mileage fees deposited in the Highway Trust Fund. The Eno Center recently issued a report,