Intercity Bus Service: Reforms Needed for Better Service for Rural America; Value for U.S. Taxpayers

Isolation or Integration? Intercity Bus Service and the Urban-Rural Divide

The gap between rural Americans and urban Americans is physical fact, not just a matter of demographics, culture or politics. Labeling rural America “flyover country” is accurate only if airplanes are the sole transportation mode in our vocabulary. In practice, intercity buses and trains can tie us together with practical, reliable public transportation, carrying residents of Delphos, Ohio (population 7,061) to Chicago or Columbus, and connecting Swansboro, North Carolina (population 3,744) to Charlotte or Atlanta. Currently, Delphos and Swansboro are rare examples of small towns whose residents benefit from well-run, government-subsidized medium-distance buses, a connection most rural Americans lack.

Dependable surface transportation bridges geographic divides, enabling economic and social exchange among people in different regions, integrating areas of the nation that otherwise are isolated. Current federal policies and programs recognize that theoretical potential, by subsidizing rural intercity bus services, through U.S. Department of Transportation grants to state governments. However, the way the federal government and most states currently administer that program, and the mostly random way state governments spend those public dollars, fails to optimize intercity bus service between smaller towns. Reforms at the federal and state levels are needed to improve service to riders and value to taxpayers.

The evolving intercity industry has become partly private, partly public

Intercity bus service in the U.S., roughly defined as routes of over 50 miles, has gradually evolved into a bifurcated industry with two distinct business models. One sector consists of bus companies which make a profit entirely from fares. They run mostly between large cities, which are the profitable markets. The other sector of the industry consists of intercity buses underwritten by public dollars, which link rural towns with each other and with bigger cities. Those taxpayer-supported buses are often operated by private companies, but would not turn a profit without the subsidy.

The first category of profitable, privately operated intercity bus is familiar to the public, including longtime brands Greyhound or Trailways, relative newcomers like Bolt, Megabus, Flix (which bought Greyhound), a myriad of so-called “Chinatown buses” mostly in the Northeast, and migrant-oriented lines connecting Mexico with points throughout the western U.S. Their business model is simple: they operate lines where they can make a profit from fares (sometimes supplemented by packages.) This sector has experienced financial turmoil in recent decades, and has been shedding money-losing rural routes in order to concentrate on mainline runs between big cities. The second business model, taxpayer-subsidized intercity bus service, emerged more recently, when Congress recognized this trend of for-profit carriers abandoning service to smaller towns, and enacted federal subsidies to backfill losses on rural routes where ticket revenue alone no longer covers costs.

Congress’ purpose in enacting these subsidies was not to bail out incumbent companies, but to support transportation options for small communities not situated along the remaining skeletal national networks of long-distance buses and trains, and are far from commercial airports. The ultimate beneficiaries Congress theoretically had in mind are rural Americans who need to reach the larger towns where shopping, medical centers, social or family life and other activities are concentrated. The routes also bridge urban and rural America in two directions by serving visitors, who bring tourism dollars and other activity to isolated towns.

In some parts of the country, these subsidized rural bus lines are well-designed to achieve that public purpose. Residents and visitors in Colorado, Washington State, Virginia, Oregon, Ohio, North Carolina and Vermont benefit from revitalized intercity bus services underwritten by federal funds, some of them profiled in an Eno post in 2022. Travelers in most of the other states, despite similar market needs and similar resources, don’t enjoy that quality of service. Why the disparity? The primary determinant of whether these medium-distance buses serve the public well is the commitment of the political leadership and transportation agency management of their state government.

Rural intercity bus subsidies: the opportunities and shortcomings of federalism

The rural bus subsidies are an illustrative example of the best and worst of federalism, in which federal dollars and intent are carried out by state governments – with widely varying outcomes. Most of the public funding flowing to intercity bus service originates with the US Department of Transportation, but is devolved to state Departments of Transportation, who are given a lot of discretion in how to spend the money. (This article uses the term “state Departments of Transportation” generically, recognizing the nomenclature differs in some states, such as Louisiana where it’s called the Department of Transportation and Development.) The intercity bus subsidy program, administered by the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) and known as “5311(f)” after the section of federal law that created it, is apportioned according to a formula accounting for a state’s population, percentage of residents who live in rural areas, geographic size, and other factors. (Rhode Island, New Jersey and Delaware are in a different league, since they have statewide transit operating agencies, appropriate to their compact size and density.) The allocation to each state government is mathematically automatic, not based on competitive applications, or on any evaluation of what benefit the subsidized bus service is (or isn’t) bringing to the people.

Federal rules for state use of these funds are simple. Congressionally-adopted statutes and/or FTA regulations provide that states devote the 5311(f) budget to intercity bus services which link rural areas with larger towns or cities and/or connect to other longer-distance bus or train lines, are run on a publicized schedule on a set route, sell tickets to the general public, accommodate luggage and comply with the Americans for Disabilities Act. The routes are generally more than 50 miles long, and have limited stops, designed for medium- to long-distance travel, generally not for daily commuting to and from work. Many run once or twice a day, some only a few days per week. These intercity routes deploy highway-suitable motorcoaches (often equipped with lavatories, reclining seats, wi-fi) or medium sized buses.

The Bustang. Sponsored by the Colorado Department of Transportation, in part with federal dollars, operated on contract by ACE Express Coaches, Inc.

Other than adhering to these broad standards, state governments have a lot of discretion in choosing how to spend 5311(f) funds. Federal oversight of these expenditures is far looser than federal oversight of urban transit systems. Most significantly, states are granted the authority to make grants to (or sign contracts with) private, for-profit companies without conducting a transparent public procurement open to competing bidders. By contrast, any urban transit agency using federal dollars to pay an operating company is required to regularly put that contract out for bids, so that a variety of vendors are invited to compete fairly.

Urban transit agencies are also expected to inform and involve members of the public in planning, and document how the agency has attempted to understand the needs of representative riders. By contrast, while 5311(f) rules impose some minimal requirements for states to conduct planning and market assessments, not all state Departments of Transportation, which are primarily highway agencies, choose to develop the capacity for market surveys or study the impact analysis of bus service.

This governance structure for subsidized intercity bus service, with ambiguous expectations at the national level and political neglect at the state level, reduces the likelihood of achieving the intended outcome of better medium-distance bus service for rural Americans. The lackadaisical federalist approach is evidenced by the FTA’s inability to even report how much it disburses each year in 5311(f) monies. In many cases, state governments default to spending the federal funds to underwrite longstanding routes of “legacy” carriers, such as Greyhound, which once were profitable but are claimed to be (by the applicant company) at risk of discontinuance. More pro-active state governments choose to use the federal funds to spark the creation of new routes and schedules. All those paths – preserving existing routes, modifying them, or creating new ones – are justifiable policy choices. The problem is that most states do not currently make those choices in a deliberate, transparent way that assures the best use of tax dollars to benefit riders.

Virginia Breeze Bus. The Old Dominion became a leader in intercity bus and rail service partly by removing that responsibility from under the old Highway Department and creating a new Commonweath Department of Rail and Public Transportation.

Whether a state chooses to preserve existing bus lines of incumbent companies, or to modify the network and solicit new companies, or some combination, the benefit to the public depends on how wisely the agency makes that decision, and by what criteria. A few state DOTs are deliberate and strategic in deploying 5311(f) dollars, but most are not. The 5311(f) program is an example of a general phenomenon about state DOTs identified by the Brookings Institution: “States typically detach the programming of funds from their long-range planning and performance, enabling them to invest without aligning spending to published goals and performance targets.” In short, many state DOTs spend a lot of money, particularly on highways but to some extent on buses, without explaining what they’re trying to achieve.

A handful of states leads the way

The state governments exhibiting strong leadership on intercity bus service are noteworthy for their heterogeneity. They include small states and large states, Republican-led states and Democratic-led states, and are located on the west coast, in the mountain west and Midwest, and in New England and the Southeast. What they have in common is dedication to fiscal responsibility, market orientation, good service to passengers and accountability to taxpayers.

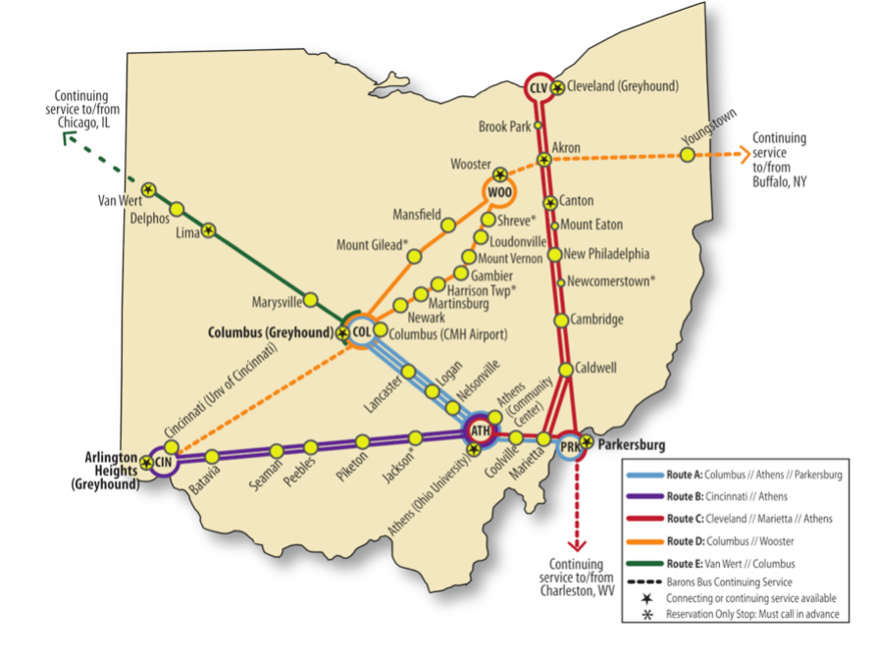

Ohio Go Bus. The Buckeye State’s DOT uses federal dollars to operate bus lines designed to link “cities and rural areas in the state of Ohio…and connect with national bus lines” to external destinations like Pittsburgh, Buffalo and Chicago. Segments are operated by private companies who win a competitive bidding process.

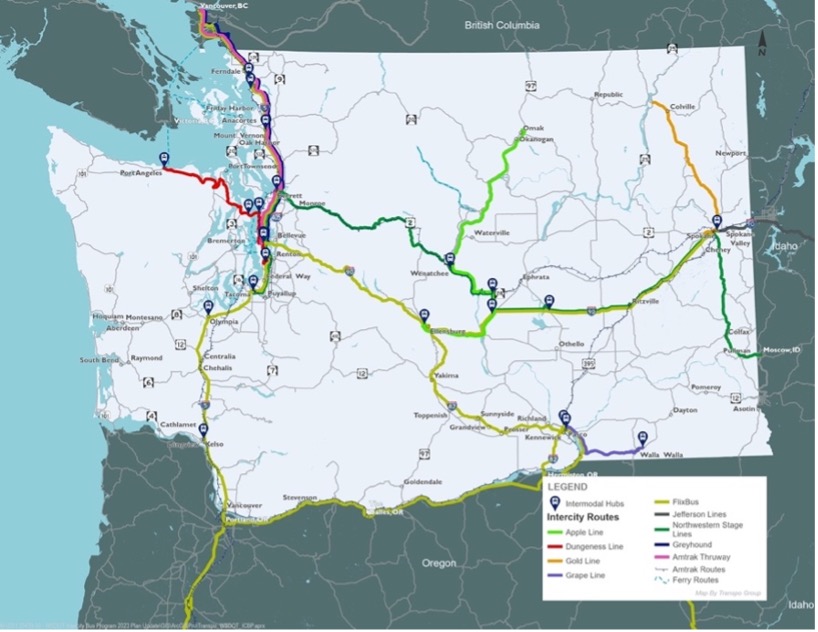

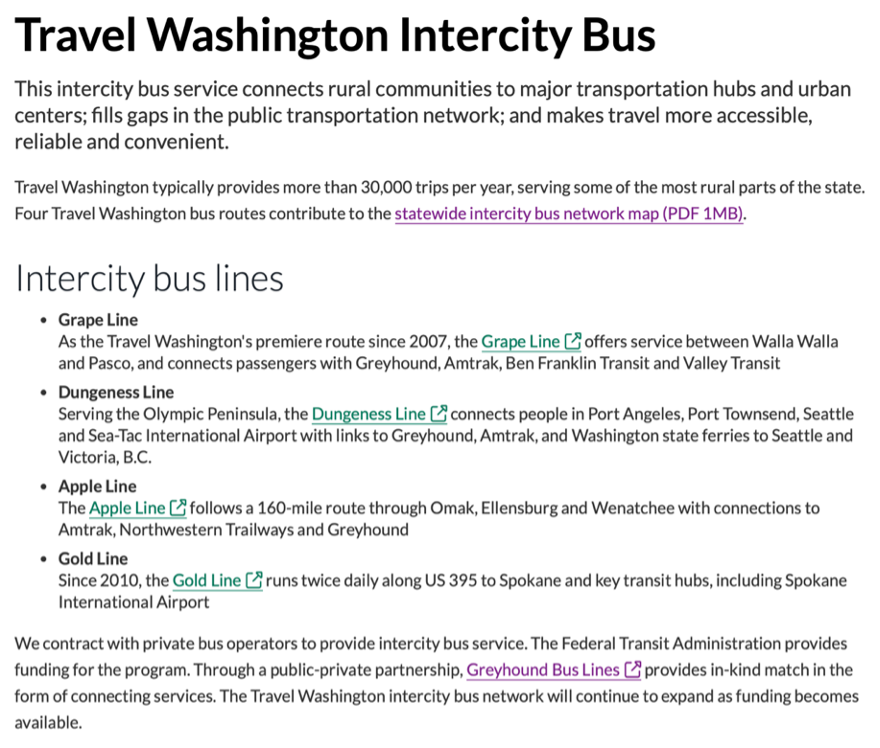

Colorado, Washington State, Ohio, North Carolina, Vermont, Oregon and Virginia spend 5311(f) funds with explicit strategies, identifying routes and soliciting bids to select operators. Residents and visitors benefit from services like Colorado’s “Bustang,” operated by ACE Express Coaches Inc., subsidized by Colorado DOT, Washington State’s “Travel Washington” routes like the “Apple Line,” Ohio’s “GoBus,” and Virginia’s “Breeze,” to name a few. North Carolina and Virginia agencies even cooperate to connect bus routes across their state line. (California and North Carolina also do a good job of linking “Thruway” buses to passenger rail lines, with California boasting the largest network in the nation.)

These competent state governments follow these basic steps:

- The state government analyzes which rural parts of their state are most in need of medium-distance bus service. They ask, where are the underserved markets with the most potential? What connections do their constituents need?

- The state government pro-actively specifies routes and frequencies and schedule parameters, to best meet the diagnosed demand.

- The state government solicits multiple entities, public or private, to submit competing bids to operate the buses. Once the state selects the most attractive offer, it rigorously oversees the contractor’s performance, to ensure constituents are receiving a high standard of reliability, punctuality, cleanliness and safety.

- In some cases, the state government brands and markets the services via a unified web site, so that riders can easily plan their trips, buy tickets, and generally get around easier.

These leading state DOTs demonstrate the positive feature of federalism, which allows state governments to be innovative in using federal dollars to meet local needs, without someone in Washington D.C. telling them exactly how to do it. Residents of Denver ride the Bustang to go skiing near Glenwood Springs, while residents of Grand Junction ride the other direction to get to Bronco games. Ohioans can take a Go Bus bus from Delphos to Columbus to reach the Ohio State University. Residents of remote towns on the southern Oregon Coast ride the Point bus to inland Rogue Valley points where the large medical facilities are. North Carolinians can take a bus from Swansboro to Wilson to connect to an Amtrak train to Savannah or New York City. These diverse Americans receive these different variations of bus service because their respective state governments made an effort to understand the public’s needs in their particular territory, and selected the right operator to meet those needs.

Travel Washington Intercity Bus. Washington State DOT conducts extensive public outreach and market surveys to determine where the public subsidies for medium-distance bus lines should be spent to have the greatest positive impact on Washingtonians’ access and mobility.

Washington State DOT provides an admirable example of transparency: their web site provides travel information to the everyday rider, and also identifies the company which won the operating company and cites to the dollar the amount of public funds the company is receiving. This accountability builds voter confidence in government.

Washington State DOT Web Site. Washington’s state government communicates extensively with riders, showcasing the state-supported services and connections, explaining the sources of funding, and soliciting consumer feedback.

Constituent satisfaction has encouraged the Washington State Legislature to increase transit funding in recent sessions.

The inverse downside to federalism is typified by state governments which receive the federal money that automatically flows to them, but don’t manifest any strategic intent to spend it well. Most Governors and state legislatures do not set expectations for their agencies to improve intercity bus service. Many state DOTs, which have negligible expertise about any mode other than highways, provide little information on how and where 5311(f) funds are spent, let alone inform their residents on how to find a bus route. In the absence of meaningful service standards, performance measures, or criteria for route selection, many state governments simply turn over their 5311(f) funds to longstanding incumbent operators, primarily Greyhound, to continue running routes they have run for decades, without regard to whether those routes have the highest beneficial impact on the residents of the state today. Most states award grants to bus companies without requiring competitive bids, and without rigorously overseeing performance. State governments, through what are essentially their highway departments, are handing public money over to private companies with very little accountability for results.

Public agency contracting with private transit operating companies, done right, provides excellent service to riders and value to the taxpayers. State DOT subsidies to private bus companies, as practiced in most of the U.S., is simply corporate welfare.

Recommendations for State Governments

More state DOTs should emulate their pro-active peers like Colorado, Ohio, North Carolina, Washington State, Virginia, Vermont and Oregon. The proven practices for leaders who care about intercity bus riders and value for the taxpayer are:

- Assess needs and identify top markets for medium-distance bus service, including connections to adjoining states. Do not simply default to subsidizing the same services that have been running for decades. Examine the results being achieved by incumbent operators and routes, and consider opportunity cost as part of the equation.

- Invite competitive bids from private companies to operate the services for fixed periods.

- Oversee performance of the contractors, to get best value for taxpayers and riders.

- Publicize the service to residents and visitors.

- Be active in the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Public Transit Council, which provides valuable opportunities for state staff to learn from their peers.

- Contribute your data to the FTA’s on-line National Intercity Bus Atlas, to provide more information to potential riders.

Recommendations for the federal government

While most of the responsibility and opportunity rests with the state governments, Congress and the federal executive branch could also do more to optimize the expenditure of 5311(f) dollars. FTA’s current institutional indifference is illustrated by its inability to report how much it currently spends on 5311(f) services. (The author made several requests to the FTA, and was told nobody tracks these 5311(f) expenditures, remarkable as that seems.) In addition to more fiscal transparency, FTA would serve riders and taxpayers well by setting clearer standards, without infringing on state governments’ flexibility to innovate to serve their citizens in different ways:

- To the extent allowed under law, FTA should more vigorously encourage states to be more market-oriented, by undertaking more rider-responsive planning and route selection, and using competitive bidding to attract the best private sector solutions.

- FTA could build on its prior joint efforts with the American Public Transportation Association (APTA) and the Public Transit Council of AASHTO to extend valuable peer exchange opportunities among the states. FTA, APTA and AASHTO could strengthen their roles as good sources of technical assistance, bolstering expertise on intercity bus issues.

- When Congress re-authorizes federal transportation policy in 2025 or 2026, it should add provisions to make the 5311(f) program more responsive to market needs (riders’ interests) and more accountable in how public dollars are doled out to private entities.

Making the most of federalism

When US passenger railroads were losing money in the 1960s and 1970s, the response from Congress was a “unified national” approach, with optional opportunity for states to supplement it: Congress created Amtrak as a nationwide entity, with provisions for additional financial contributions from states that chose to buy additional service from that one monopoly nationalized provider. (The pros and cons of that approach are a subject for another day, but in the five decades since, arguably the most growth and innovation in passenger rail has originated with state governments, while the stagnant national long-distance network, which is the exclusive province of Amtrak, has deteriorated.) By contrast, when Greyhound and other intercity bus companies were losing money in the 1990s and 2000s, Congress took the opposite approach it had taken to passenger railroads back in the 1970s: rather than nationalize Greyhound as a “rubber-tired Amtrak” that would be a perpetual ward of the federal government, Congress created 5311(f) with a “state centered but federally funded” structure. That approach offers flexibility for state governments to tailor their bus programs more than they are able to do with Amtrak programs, but also depends on state leadership that cares about rural bus service and the people who use it.

Whenever federal dollars flow through the hands of state governments – whether that’s for Medicaid, housing, community development block grants or transportation – the value delivered to Americans in each state depends on the balance of prescriptiveness at the federal level and political responsiveness and managerial acumen at the state level. In the case of 5311(f) subsidies, both federal officials and state officials should tighten up their sense of purpose in subsidizing intercity bus services, and their procedures for interacting with private companies. By becoming more deliberate and disciplined, the US DOT and their grantees in State DOTS could provide more mobility and access benefit to rural residents and travelers.

David Bragdon is a lifelong transportation maven who has spent a lot of his life in New York City and Portland, Oregon. He has been an agent for Panamax grain ships on the lower Columbia River; President of an elected regional government and Metropolitan Planning Organization; the Executive Director of TransitCenter, an applied research and advocacy foundation; and a taxi driver. His transportation pursuits have included jump-seating 747 freighters into the Soviet Far East; taking passage on a Dutch containership through the Strait of Malacca; and riding in the locomotive of a freight train from Council Bluffs to Des Moines. He currently lives 200 meters from the banks of the Hudson River.