Intercity bus travel is far from novel in the United States — in fact, for much of the early-to-mid 20th century, it was the go-to option for long-distance travelers. The decline of the bus industry since 1970 has of course been well documented, attributable to reduced passenger demand amid rising personal car use and competition from air travel. The federal deregulation of the industry with the Bus Regulatory Reform Act of 1982 did not lead to expanded services and competition. Per a 2005 study of intercity bus service by the U.S. Department of Transportation, the number of communities served by daily intercity bus service declined five-fold from 1965 to 2005, from 23,000 to roughly 4,500.roughly 4,500.

However, COVID disruptions notwithstanding, intercity bus travel has enjoyed a “renaissance” since the early 2000s, led in large part by private express bus operators meeting passenger demand in large cities like Boston, New York, and Washington. State governments stretching from the mid-Atlantic to the Pacific Northwest have joined the revival, too, aiming to bridge gaps in intercity transit not covered by Greyhound, Peter Pan, Amtrak, and others. A handful of states are connecting long-ignored rural areas and smaller locales with publicly overseen, multi-line services with their own unique branding. These systems are supported by rider-paid fares, state funding, and the Federal Transit Administration’s 5311(f) program.

Among the earlier examples of such state-led efforts in this wave are Ohio’s five-route GoBus inter-city system, Travel Washington, and Oregon Point, which debuted in 2009 and runs four lines through the Beaver State. These and others are noted in the table below. “It is a new thing to have essentially all the participants looking like one brand,” said Brandon Buchanan, director of regulatory affairs for the American Bus Association, pointing to the last 15 years in particular. “That trend is definitely new.”

(Note: this non-exhaustive list omits operators of smaller, non-coach rural services that do not compete in the larger inter-city travel market. It also does not include fixed-route services planned, administered, and operated wholly by private carriers (even if they received state subsidies), such as Hoosier Ride in Indiana, BeeLine Express in Kansas, or Vermont Transit Lines in New England.)

| State |

Service/Brand |

Start of Service |

Routes |

Fares |

Website |

| Colorado |

Bustang |

July 2015 |

9* |

$1-45 |

ridebustang.com |

| Ohio |

GoBus |

November 2010 |

5 |

$5-30 |

ridegobus.com |

| Oregon |

Oregon POINT |

April 2009 |

4 |

$3.50-52 |

oregon-point.com |

| Virginia |

Virginia Breeze |

December 2017 |

4 |

$15-60 |

virginiabreeze.org |

| Washington |

Travel Washington |

December 2007 |

4 |

$5-50 |

gold-line.us, grapeline.us, gold-line.us, appleline.us |

*Includes three primary service routes between larger cities and six rural-connecting “Outrider” routes

These services are typically not as high-capacity or grand in scope as a passenger rail network, as is being pursued by the federal government, Amtrak, and state partners. State-sponsored bus lines often are not as frequent and or financially self-sustaining as the legacy for-profit services — Greyhound, Peter Pan, and Coach USA subsidiaries, for instance — that collectively make up the vast majority of U.S. intercity bus service. But intercity bus networks in the states listed above are connecting cities and rural areas that might lack rail lines or profitable passenger volumes. They require millions, not billions, in public investment, can take advantage of existing highway networks without major infrastructure changes, and can draw on federal funds already allotted to states (see above “5311(f) Funding” box).

Two examples — Colorado’s Bustang program, administered by the Colorado Department of Transportation, and the Virginia Breeze, spearheaded by the Virginia Department of Transportation — have exceeded ridership and revenue expectations by connecting key locations and employing distinctive branding.

Colorado Bustang

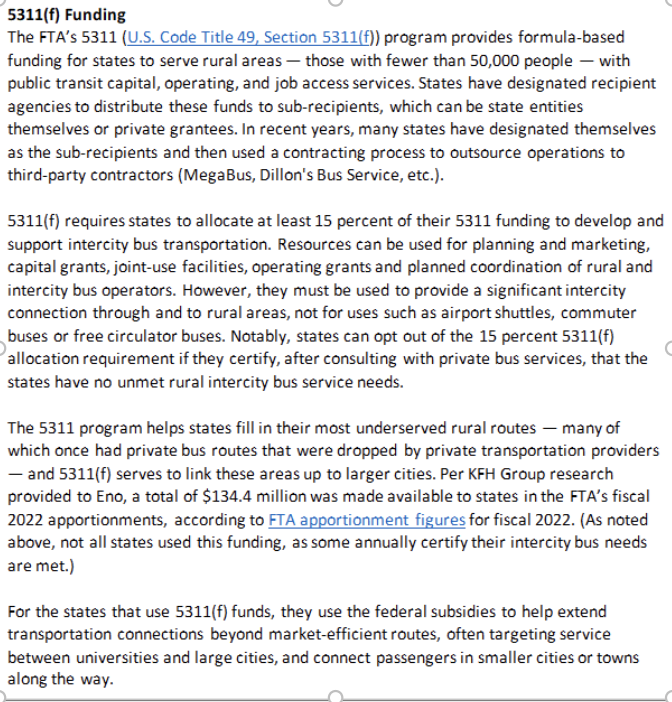

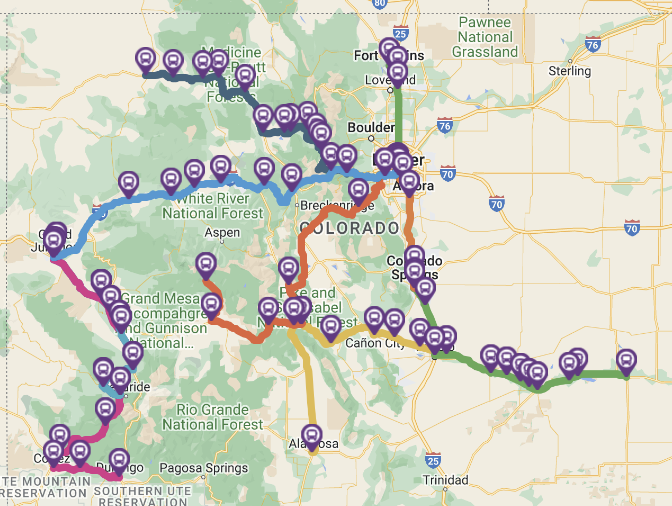

Bustang, a Colorado Department of Transportation-managed service operating since 2015, runs three main routes to connect the state’s largest cities and attractions. Two routes traverse the oft-congested north-south I-25 corridor — one to the north of Denver, connecting the capital city with Fort Collins, and another to the south between Denver and Colorado Springs — and a third, farther-reaching east-west line runs 243 miles along I-70 between Denver and Grand Junction (see map below).

The state has since expanded to more rural areas through its Bustang Outrider service, launching three additional routes in 2018. Outrider buses are paid for with a mix of state and FTA funding. Amber Blake, director of CDOT’s Division of Transit and Rail, said the 5311(f) allocation plays a major role in creating rural transit connections. “It’s the bridge,” she said. “It allows the local services to coordinate with the inter-city bus, to get you a rural trip to Denver” or other cities.

Adult walk-up fares for the three main Bustang routes range from $9 and $12 on the north-south lines to $43 for the length of the I-70 line, while Outrider fares range from $2 to $45 across six lines, depending on the destination. Golden, Colorado-based Ace Express Coaches operates the Bustang fleet.

A map showing the three main Bustang lines — Fort Collins-Denver (green), Denver-Colorado Springs (light orange) and Denver-Grand Junction (blue) — and six Bustang Outrider expansion lines serving rural areas. (Credit: CDOT/Bustang)

Ridership surpassed initial projections in its early years; the system had 102,000 riders in its first full year, well above initial state projections of 86,000 riders. According to CDOT-provided figures, it recorded a more than 50 percent ridership increase during its second year (156,000 total riders) followed by a 25 percent bump (194,000) in year three and a 23 percent increase (238,000) in 2018-2019, the last full year of operations before the Covid-19 pandemic. Bustang’s 38 percent farebox recovery rate beat its pre-launch forecast by eight points and then climbed to 53 percent and 58 percent in 2016 and 2017, respectively. As of fiscal 2020-21, the system’s fares were covering three-fifths of its estimated $3.5 million in annual operating costs, or about double initial projections of 30 percent.

As with virtually all transit programs, COVID dealt a major blow to Bustang’s performance. CDOT shut down Bustang for the first three months of the pandemic to discourage travel and continued with reduced service throughout 2020, though passengers have been coming back since it resumed full operations in 2021. Per CDOT figures shared with state officials in May, ridership was at 75 percent of March 2019 levels, the state’s pre-pandemic benchmark, and the number of east-west line users specifically was actually up 36 percent in March 2022 (an all-time high of over 94,00 passengers) from March 2019, though routes running north and south of Denver were down 55% and 62%, respectively. The north-south lines cater heavily to commuters, many of whom have continued working remotely during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

Picking back up on Bustang’s pre-COVID momentum, a three-year, $73 million pilot expansion announced by the state this spring will aim to dramatically expand service while covering expected funding gaps from “COVID-related ridership challenges that may last until 2023-24,” according to Blake, of CDOT’s Division of Transit and Rail. Under the expansion plan, round trips on the I-25 North and South routes will double from six to 12 on weekdays and triple from two to six on weekends by 2024. On the east-west I-70 route, trips will increase from four daily to between 13 and 15 in the next two years. Additionally, CDOT is offering a new service called Pegasus, consisting of passenger vans with room for up to 11 riders and running year-round between Denver and the mountain town of Avon. The service is geared toward mountain travelers willing to shed their cars for a shared ride up in a shuttle that will carry their gear.

Of the $73 million in new state funds, CDOT is putting $11.3 million towards more buses, $30 million to expansions of all three main Bustang lines, and the remainder towards covering future revenue gaps between those costs and farebox recovery and from rising inflation, Blake said. She noted the expansion plans will effectively triple Bustang annual operating costs from roughly $3.5 million to $10 million.

“As we’re growing and scaling, the assumptions that we’re making are the 30 percent farebox recovery — that would be the standard industry-wide,” Blake said. However, CDOT is conducting extensive outreach and marketing for its new services in hopes of drawing in more riders and building up demand, she said.

Colorado’s Bustang expansion is directly influenced by the state’s growing congestion on highways, and a broader, sustainability-minded push to encourage more modal shift to public transport. The state is betting that by investing in high-quality intercity bus services and introducing options like Outrider, drivers “will actually give transit a try and shift their mode,” Blake said.

Virginia Breeze

Virginia launched the Breeze, a four-line inter-city bus system (see map below), in late 2017 to help connect cities, universities, and other major destinations through the commonwealth and D.C. The Breeze’s inaugural line, the Valley Flyer, connects Washington D.C.’s Union Station to Blacksburg (home to Virginia Tech) with six intermediary stops along the I-81 corridor.

Touting higher-than-expected ridership and farebox recovery after a year, DRPT expanded the service with new lines in August 2020. One of those, the Piedmont Express, runs along the 250-mile stretch between D.C. and Danville in southern Virginia, with stops in college towns like Charlottesville and Lynchburg. The other, dubbed the Capital Connector, traverses a 190-mile route from Washington through the state’s capital of Richmond and out to Martinsville.

A fourth line called the Highlands Rhythm, connecting Washington and the city of Bristol at the Virginia-Tennessee border, began running buses daily in November 2021.

A map of the state-administered Virginia Breeze intercity bus service, which launched in 2019 and has since expanded to four lines.

Walk-up fares range from $15 for the shortest trip to $60 for the longest full-length journey between Washington and Bristol. The Breeze runs one daily bus in each direction on all four lines, though the state has flexibility to run additional service on holiday weekends based on demand. The service is administered by the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) and operated under contract by Dillon’s Bus Service, a Maryland-based subsidiary of Coach USA.

The Breeze’s Valley Flyer line had 19,300 riders during its first year, nearly tripling initial projections of 7,125 users, and logged an 81 percent farebox recovery rate for operations. Virginia uses 5311(f) allocations to cover any operating costs not paid for by fares. So, of the $1 million operating costs for the Valley Flyer’s first year, farebox revenues paid for approximately $800,000 and the remaining $200,000 was subsidized by 5311(f).

DPRT had projected first-year annual ridership for two expansion lines — the Piedmont Express and Capital Connector — to reach more than 15,000 upon their launch in early 2020, but the Covid-19 pandemic led the state to suspend service for nearly four months and delayed the launch of both services until that August.

Similar to their peers in Colorado, Virginia transportation officials have more recently touted a systemwide rebound. Per DRPT-provided figures, the number of riders on the system’s initial three routes (the Highlands Rhythm hadn’t launched yet) doubled from the first quarter of 2021 to the first quarter of 2022, from 3,918 passengers to 7,848. Farebox revenue similarly doubled along all three routes, from $136,682 to $282,289. In both quarters, about 70 percent of the passengers across those three lines were on the Valley Flyer route (or 54 percent in Q1 of 2022, if including the newly launched Highlands Rhythm). Despite the apparent bounce back, passenger totals and farebox revenue were still well below pre-pandemic levels and projections.

DeBruhl said running a state-administered service with its own branding, such as line names that reference regions of the state, helps to create a sense of ownership. (She noted Virginia looked to similar branding examples from Colorado and Washington state when creating its Breeze program.) She also said state-contracted services wind up taking different approaches to service planning than private carriers — for example, by starting up new lines like the Piedmont and Capital Connector routes that can connect economically depressed and transit-underserved parts of the state, even if “we knew they would not be as successful” in terms of immediate ridership and farebox recovery.

All told across the Breeze’s four lines, total annual operating costs have increased to $3.2 million since its launch in 2017. With each expansion, ridership has not kept pace with the immediate successes of the Valley Flyer route, due in part to pandemic-induced closures and suppressed demand, and because these expansions cater to far more rural areas with inherently lower ridership bases. That’s by design.

“We’re making trade-offs knowing it’s going to dilute the ridership a bit,” DeBruhl noted. “It was a very deliberate decision on our part to do those projects anyway because it was about accessibility. It was not about turning a profit.”

The system could continue to expand — DRPT said last month that it is conducting a study for the possibility of adding a fifth Breeze route through the eastern portion of the state. It’s scheduled to be completed in late 2022.

Using intercity buses to expand transportation options, influence mode shift

Much of the recent national discussion about how to improve city-to-city connections and better service rural areas in between has focused on the $66 billion provided by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) for Amtrak, which the service plans to use as part of a $75 billion plan to connect 39 new rail routes and service to 160 more communities. However, publicly administered intercity bus service can play a significant role in fulfilling these goals as well. Administrators of the Bustang and Breeze programs expressed optimism about the broader growth broader potential of state-supported intercity bus systems.

While IIJA did not significantly or explicitly expand intercity bus service funding, it did increase contract authority for 5311 formula funding from $673.3 million in fiscal 2021 to $875.3 million in 2022, and then upwards annually in steps to $959.6 million by fiscal 2026. Thus, with an annual average of $916.3 million in 5311 program contract authority over the next five fiscal years, that amounts to a roughly 36 percent increase from fiscal 2021. This boost could in turn provide greater resources to states under the 15 percent set-aside for intercity bus service under 5311(f) and, if done well, complement the investments in passenger rail.

With this context in mind, states need to be leaders in leveraging the flexibility and cost efficiency of intercity bus to improve city-to-city connections. Given the scale and legacy of privately companies that run buses between urban areas throughout the country, publicly managed models of bus service are not meant to be a replacement or alternative to existing connections. They can, however, help to fill in service gaps left over by private carriers that ceased operating through rural areas years ago, and do so with a hands-on management and branding approach from public agencies that already have a ready stream of resources coming from annual 5311(f) funding.

The following recommendations will help achieve accessibility, environmental, and fiscal goals of state transportation departments.

Leverage the low costs of the bus

Buses do not require nearly the same levels of capital investment or agency partnership as heavy rail, thanks to the existing right-of-way already established by roadways. Expenses include acquiring vehicles, planning and marketing the services, and paying for private carriers to operate and maintain them.

The relatively low cost allowed Virginia to quickly quadruple the number of lines in its system since it launched in 2017. While annual operating costs have roughly tripled from $1 million to $3.2 million, this is a rounding error in Virginia DOT’s $7.54 billion budget. Colorado is making greater investments in its system, including a one-time $11.3 million expenditure on increasing its fleet size, but even while doubling or tripling service on its main routes, operating costs are still set increase from only $3.5 million to $10 million annually — a relatively small increase compared to other state investments.

“The needed subsidies are relatively low compared to other mobility options,” said Schwieterman, of DePaul. “Compared to rail, it’s remarkably cost-effective given that there are very low facility or station costs.”

Build a brand that riders will recognize and trust

State leadership and planning for these services allows for building stronger brand identities and close oversight and involvement with daily operations, including monitoring farebox recovery and ridership metrics. These elements can make programs like Bustang and the Breeze more responsive to rider demands and needs to fill in service gaps.

Schwieterman noted branding really can play a role in creating a customer base: “Branding gives customers confidence they’ll have a quality experience. Many travelers are wary of hopping on an intercity bus, fearing it’s going to be an unpredictable experience. Investing in a brand creates a buzz that can spread rapidly among households with limited car access.”

State-administered service allows public sector goals to be closely monitored compared to an arrangement with wholly private bus lines. Examples of metrics include on-time performance, customer satisfaction, safety, and cleanliness, in addition to tracking ridership and farebox recovery. States can include incentives and penalties in the operating contracts to ensure that the standards are met.

Connect the bus service to other intercity services and local transit

Along with providing access to key destinations, any new transit service should focus on connecting to larger and smaller modes of transit, from Amtrak to local buses and bike routes. Two of the more well-tested state-supported intercity bus services, Oregon POINT and Travel Washington, established routes with stops at various Greyhound and Amtrak station connections (Oregon’s website also includes links for Amtrak tickets with its route maps). In both of our case studies, newer services have likewise introduced routes connecting to rail stations in Washington and Richmond, or in Denver, Grand Junction, and other Amtrak-served cities. Smart planning not only makes a physical connection to other modes, but times the service to minimize transfer wait times when possible.

Blake, of CDOT, said fostering these connections is essential if states really want to convince more drivers to opt for the bus instead. “When we look at a challenge of getting folks to shift their mode, it’s convenience and freedom. We live in America and freedom is important to us,” she said. “When you’re shifting the mode, I think it comes down to, is it convenient? Does it actually connect to local service?”

Plan an adaptable service

Successful intercity bus programs have the ability to adapt to changing demands and needs of the traveling public. Before COVID, running an intercity bus service responsive to changes meant being prepared to increase service on days with high demand, or have a process in place for launching new lines. More recently, being adaptable often means an ability to adjust service as needed for changing commuting patterns.

In Colorado, the proliferation of remote work has led to long-term reduced ridership on certain Bustang lines or during parts of the day that once had more robust ridership. But CDOT plans to boost bus trips on certain lines with higher demand and introduce new services like Pegasus that cater to occasional or weekend travelers. DRPT is also launching new services, and DeBruhl noted that the system is prepared to run more buses during times when students are traveling and adapting future service as needed.

Even without pandemic-related ridership disruptions, both systems have said they had planned to use their more popular, well-traveled routes to help cover some costs for lesser-ridden expansion routes to further-flung areas. However, the debut of newer lines inevitably pulls down farebox recovery rates systemwide. Combined with long-term ridership losses from more people working from home after COVID, this can make it more difficult to justify spending on planning and servicing new routes or bolstering fleet sizes to offer more robust service.

In order to meet their climate, equity, and congestion goals, states need to serve unmet demand for intercity transit and encourage more drivers to shift from their cars to modes like train and bus. This can fill important gaps that for-profit bus companies are unable to fill. And while the opening of new passenger rail service might take years to launch, intercity buses can launch quickly and help build and justify the demand for more expensive service. This makes intercity bus pilot programs an inherently less risky prospect for states seeking interim or forward-looking solutions.

This piece has been corrected to reflect that Virginia DRPT, not VDOT, administers the Virginia Breeze bus service.