Bus purchases represent one of the largest investments for most transit agencies in the United States. According to the American Public Transportation Association, in 2020 about 11 percent of all transit capital expenditures went toward passenger bus vehicles (known as “rolling stock”.) The standard 40-foot bus is the workhorse of public transit in the United States, responsible for over 58 percent of all transit trips. Today, however, there is concern that the over-customization of new buses could be leading to higher costs for transit agencies and reducing the competitiveness of U.S. vehicle manufacturers.

Agencies customize buses for a host of reasons. For example, they provide unique branding for their vehicles with exterior wraps and matching color schemes, which helps transit agencies to be visible in their communities. Agencies may also customize to meet certain HVAC and engine needs specific to the geographic settings or climate patterns of their communities.

But recent analysis of bus procurements suggests customization could be driving up costs in a detrimental or counterproductive way. When designing a bus for a new transit agency partner, an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) must go through a rigorous configuration review and may need to do additional engineering work to meet an agency’s requirements. Manufacturers struggle to pass these costs on to the purchaser, making it difficult for them to stay in business. This is not just a problem for those companies, but fewer manufacturers reduces competition and hinders national public policy goals, such as Buy America.

On August 8, Proterra Inc, an electric bus manufacturer, filed for bankruptcy. While Proterra’s path to bankruptcy was the result of multiple converging factors, the company’s Chapter 11 filing notes that “transit agencies demand highly customized buses that align with the other buses in their respective fleets. Therefore, the manufacturing process requires customization, which makes scaling the business difficult and requires an extensive amount of working capital.” Another manufacturer, Nova Bus, cited profitability challenges as the motivator for their withdrawal from the U.S. market by 2025. Our recent analysis suggests that excess customization was a contributing factor.

Drawing a clear connection between excess customization and costs is admittedly difficult. For one, “excess” is a subjective term and equipment that may have been considered optional in the past (e.g., security, farebox, and GPS technology) are now considered industry standards by most transit purchasers. Another issue that makes this analysis challenging is that bus manufacturers do not make their prices for standard base buses (which do not include the aforementioned options for security, farebox, and GPS equipment) publicly available.

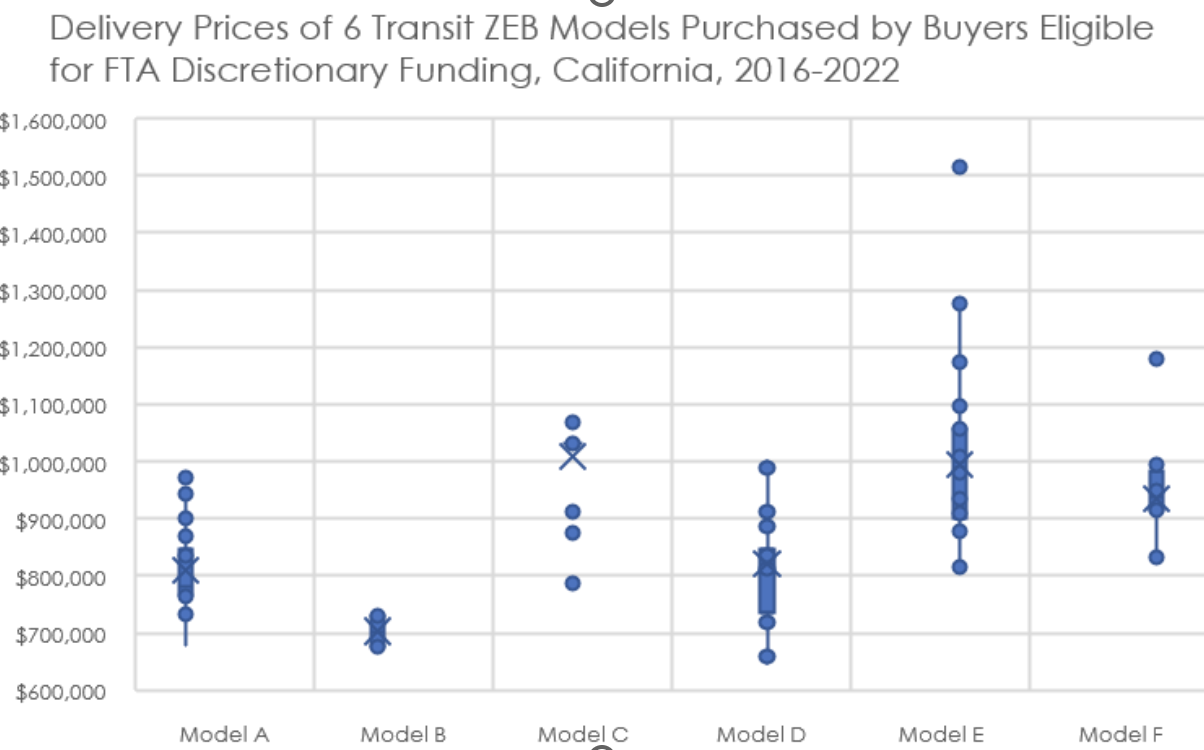

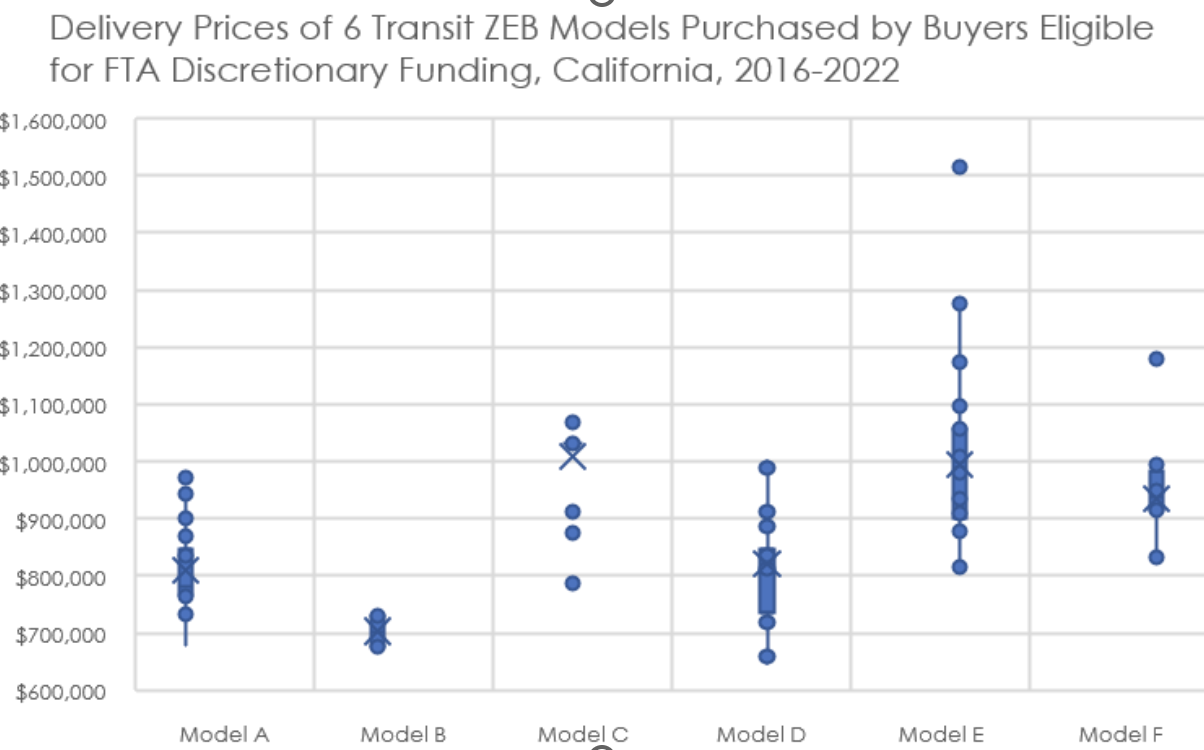

However, an analysis of data from California’s Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Program (HVIP) offers a window into cost variance with transit bus procurements. The program was established in 2009 by the California Air Resource Board (CARB) to provide incentives for the purchase of zero-emission buses (ZEBs) to transition away more quickly from more heavily polluting vehicles. Data from this program from 2016-2022 spanning 255 purchased orders makes clear the vast range of purchase price for the same model of bus. For one model, even after removing the most egregious outlier, per-unit bus prices ranged from $800,000 to almost $1,300,000. The table below presents the price range for the six most popular ZEB models sold to FTA-grant eligible buyers within the California HVIP.

Source: California HVIP purchase order data, 2016-2022.

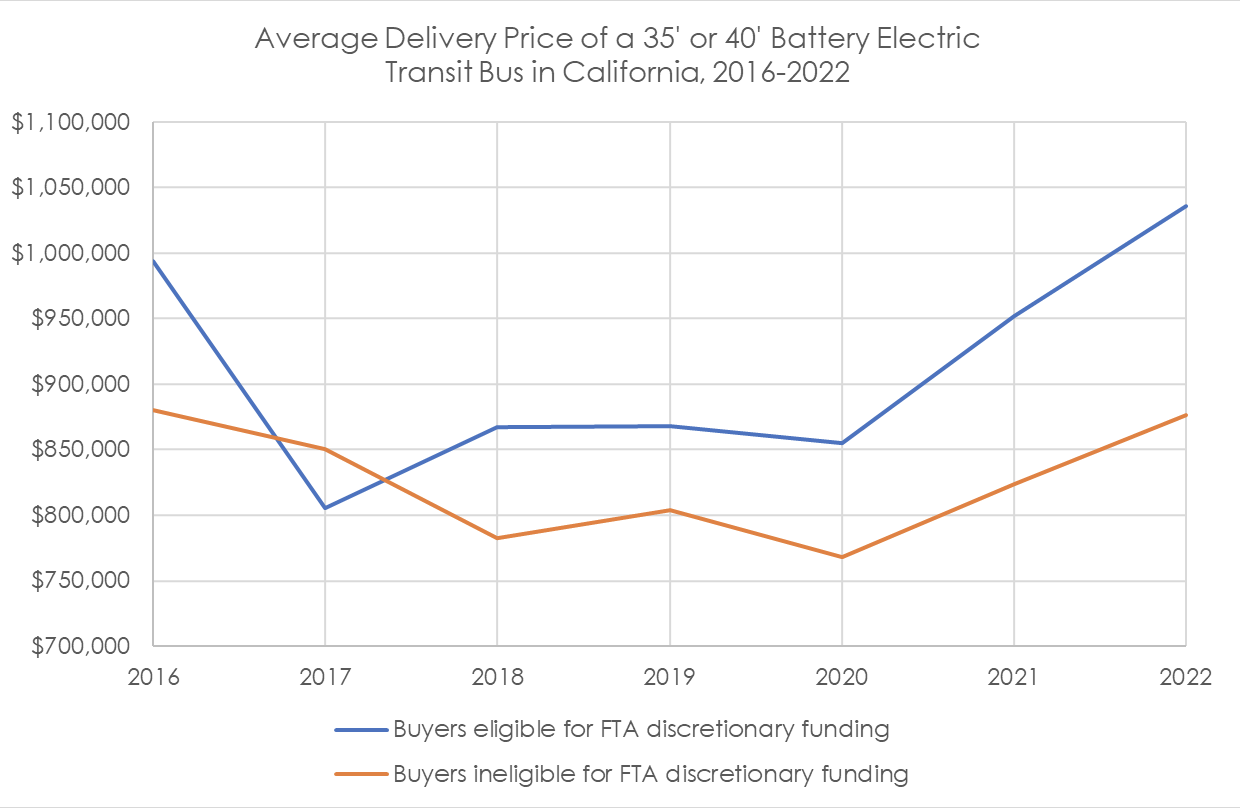

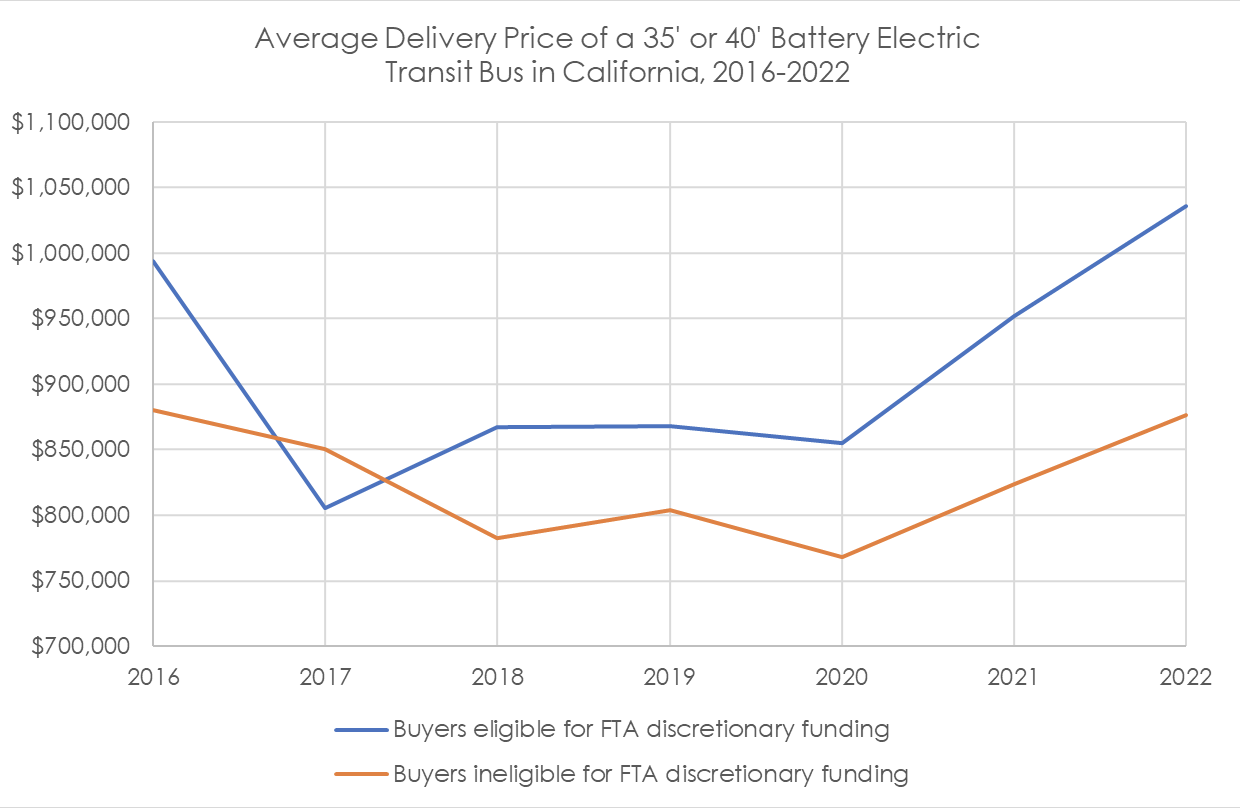

Expanding the analysis further to all transit buses purchased with HVIP in California illustrates that this is a problem specific to transit agency procurements. An analysis of 297 purchase orders for 35’ and 40’ ZEBs (14 percent of which were to buyers not eligible for FTA discretionary funding) indicates that ZEBs bought by FTA eligible buyers are consistently more expensive than other buyers since 2017. This gap has only worsened since supply chain bottlenecks and inflationary pressure in recent years have driven up industry costs.

Source: California HVIP Purchase Order Database, 2016-2022

The chart shows that the price of buses for non-FTA-funding-eligible buyers, such as airport authorities, is lower than those whose costs are borne mostly by the FTA. Many federal transit grant programs for bus purchases—like the Lo- And No-Emission grant program—cover 80 percent or more of the procurement cost, meaning the agencies don’t face large financial consequences for over-customization. Transit agencies are also more likely to customize buses to a greater degree because they often need add-ons that other purchasers do not, such as farebox and rider information technology. While some of these options may be essential to transit service delivery, others do not significantly impact the most important outcome for transit riders: getting from point A to point B efficiently and cost effectively.

What does Transit Bus Customization look like?

There are two main types of customization. The first is vendor-component specification, when a transit agency will specify a vendor for a specific component. This is commonly applied to components including HVAC systems, seats, windows, doors, and mirrors: pretty much anything that attaches to the main body of the bus. Procurement specifications often require a certain component available only from a specific vendor “or equivalent.” Procurement, engineering, and maintenance staff at large agencies sometimes have relationships with specific vendors and their sales teams and incorporate those preferences into their procurements.

While procurements are competitive between the manufacturers, component over-specification limits buying power, as it often locks agencies into certain suppliers and removes their ability to find more cost-effective options. This also makes the order more susceptible to supply chain disruptions if specific components become unavailable. Manufacturers attempt to price in this risk, but it can be challenging to do so – especially given the significant time that often elapses between when a contract is signed and when payment to manufacturers is made. As a result, industry experts suggest that there is more than over-customization that is plaguing transit bus procurements; there are also significant challenges relating to contracting process that are negatively impacting the viability of this market for OEMs.

The second type is modification to the base bus design, also called custom configurables. Manufacturers usually offer standard configurables for certain elements of a transit bus, such as seating arrangements, and customer information systems. For example, a manufacturer may offer standard configurations for one, three, or five security cameras, with specific locations on the bus. The engineering necessary for these options is done in bus development. A transit agency may opt to specify a certain location for a security camera that is different from the manufacturer’s standard configurations. This can increase costs as additional engineering is required to determine features like the wiring for the body of the bus. Additional examples include custom taillight arrangements to match the design of an agency’s older buses, or custom color requests for interior paneling or seat coverings beyond standard options.

Industry procurement professionals suggest that custom configurables are the area where customization as a whole adds the least tangible value and perhaps the most cost. Retooling a factory for a new order is expensive, as it requires engineers and designers to spend additional time ensuring that customer options will be functional. Less consistency between bus orders ultimately results in higher costs for the manufacturer and the purchaser.

Potential Solutions: There are many policy and practice options to address over-customization, as well as some of the large issues that may be harming this industry. Manufacturers could support training on new components of their preferred supplier list. In some cases, agencies are opting for specific, more expensive components because their maintenance and operations staff are already trained on them. With every custom bus order, the manufacturer must prepare a new training manual that is specific to the components on the bus. While additional training time for agency staff can increase cost, the cost reductions this flexibility could allow on the procurement side of things would likely pay-off in the long run. Standardization would benefit both the manufacturers and transit agencies.

In other cases, manufacturers or funding agencies could provide greater financial incentives to limit customer options. The federal dollars that go toward a bus purchase could be capped at a certain percentage or grants could be prioritized to agencies that limit customization. Assessing the way contracts are set up may also relieve OEMs from absorbing unsustainable levels of risk and therefore contribute to the long-term health of this market – which is in the interest in the U.S. more generally.

Monetary and other incentives work. A great example is the Clean School Bus (CSB) Grant/Rebate Program administered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The first year (2022) of this IIJA program limited the federal contribution to a certain monetary value in each school bus class with an increased cap for communities that meet one of the prioritization criteria for disadvantaged communities outlined in the law (Specifics can be found on pg. 6, here). Any additional costs created through customization would be incurred by the grant applicants, disincentivizing them to do so. Additionally, the first year of CSB also required that payment requests be submitted within 6 months of a grant award notice from the EPA, and the infrastructure and vehicles be installed and delivered by 18 months following the payment request. This accelerated timeline made it difficult to include custom configurables in the procurements, limiting their likelihood. (See rebate implementation dates here). The California HVIP, the New York Truck Voucher Incentive Program (NYTVIP), and the New Jersey Zero Emission Incentive Program (NJ ZIP) all cap the rebate or grant contribution per vehicle at a set dollar amount, likely limiting customization.

There is still work to be done. A thorough national study is needed for a larger sample size and to identify the true magnitude and breadth of the problem. More public information about base pricing would help improve our analysis. A comparative analysis of transit capital costs among international peers could also provide insights on strategies to keep procurement costs down and potentially save millions of dollars that can be better spent on critical projects to improve services for riders.