December 16, 2016

On Wednesday, December 14, Uber announced the launch of its Self-Driving Uber service in San Francisco, the second pilot of its kind in the U.S.

It was heralded with a heartwarming video and a characteristically bold press release that implored California’s state government to exercise regulatory restraint. The San Francisco-based company argued that complex regulations would stifle innovation before going on to state, “Our hope is that California, our home state and a leader in much of the world’s dynamism, will take a similar view.”

No less than 24 hours later, one of Uber’s cars with self-driving hardware was caught on camera speeding through a red light. Shortly after, Uber received a letter from the California Department of Motor Vehicles ordering it to cease operation of its autonomous vehicles on public roads.

(Source: CA DMV letter to Uber ATG’s Anthony Levandowski by TechCrunch on Scribd)

Uber has already faced criticism from some industry experts for ostensibly rushing into the autonomous vehicle (AV) space with as-yet unproven technology, as well as consumer protection groups.

Adding to the company’s troubles, San Francisco Police Traffic Company Sgt. Will Murray told reporters Wednesday that Uber did not provide advance notice of the pilot project. “I was unaware the cars have been released in the wild,” Murray told the San Francisco Examiner. “Isn’t that like the headless horsemen?”

On Thursday, San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee condemned the pilot project in a statement to the San Francisco Examiner:

“The mayor demands Uber to stop the unpermitted and unlawful testing of autonomous vehicles on the streets of San Francisco until they obtain the appropriate permitting from the DMV . . . The mayor expects Uber to do what is required by law and obtain a permit from the DMV, just like every other company testing autonomous vehicles in San Francisco,”

The first pilot conducted in Pittsburgh has largely been successful across the past several months. No significant accidents or injuries have been reported, with the exception of one incident when Uber’s self-driving cars going the wrong direction on a one-way street. It is unclear whether the human driver or automated system was in control when this happened.

Nonetheless, the company assured the public that its trained drivers and engineers were constantly monitoring the performance of its vehicles to ensure safety – while also emphasizing its efforts to map the cities in which it operated, including relevant traffic laws and patterns.

Nonetheless, an Uber equipped with self-driving hardware sped through a red light on Wednesday, a few seconds after the light turned red. It was caught on a taxicab’s dashboard camera, the video of which can be seen here.

It has not been confirmed whether the human driver or the automated system was operating the vehicle at the time.

An Uber spokesman told NBC Bay Area in a comment, “This incident was due to human error. This is why we believe so much in making the roads safer by building self-driving Ubers. This vehicle was not part of the pilot and was not carrying customers. The driver involved has been suspended while we continue to investigate.”

California Blues

While federal regulations do not expressly prohibit or restrict the development and testing of AVs, companies have typically flocked to states that provide a measurable degree of regulatory certainty through laws that explicitly allow AV testing. California was among the first of those states.

Under California state law, manufacturers and tech firms must apply for Autonomous Vehicle Testing Permits prior to operating AVs on public roads. The four-page application requires identifying information about the AV (license plate, VIN number, make and model), the names of AV each driver/operator, and acknowledgement of California’s restrictions for testing autonomous vehicles.

As of December 8, 2016, 20 firms had received AV testing permits including Google, Tesla, and GM Cruise – which is developing AVs in conjunction with Uber’s rival, Lyft.

These organizations agreed to comply with California’s AV regulations, including a requirement that a human driver is seated in the driver’s seat and prepared to immediately assume manual control of the vehicle in the event of a technology failure or emergency.

Nevertheless, Uber’s press release announcing its AV pilot in San Francisco questioned that very need to obtain a testing permit (emphasis added):

“Finally, we understand that there is a debate over whether or not we need a testing permit to launch self-driving Ubers in San Francisco. We have looked at this issue carefully and we don’t believe we do. Before you think, “there they go again” let us take a moment to explain:

. . .the rules apply to cars that can drive without someone controlling or monitoring them. For us, it’s still early days and our cars are not yet ready to drive without a person monitoring them.”

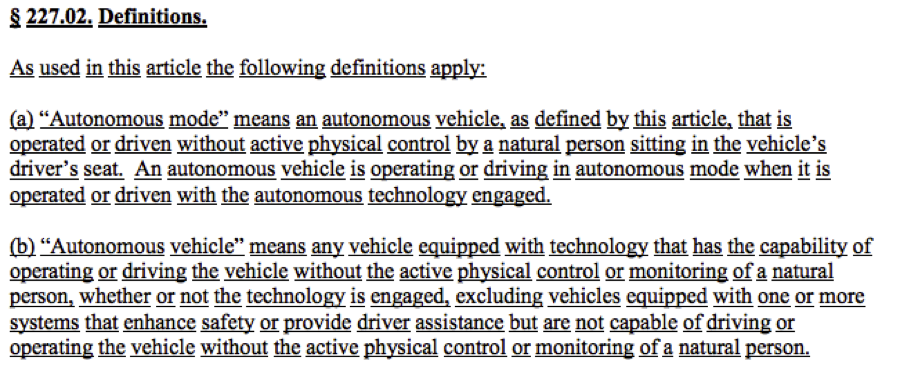

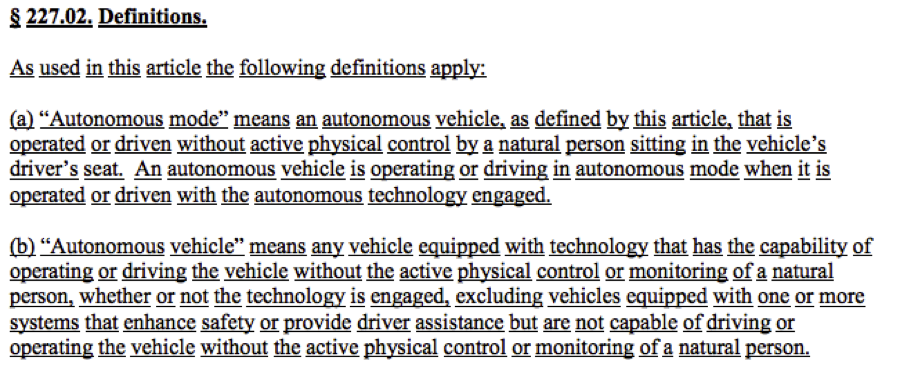

And Uber’s argument may hold up – California’s AV regulations loosely define autonomous vehicles and autonomous mode while failing to acknowledge that vehicle autonomy occurs on a gradient.

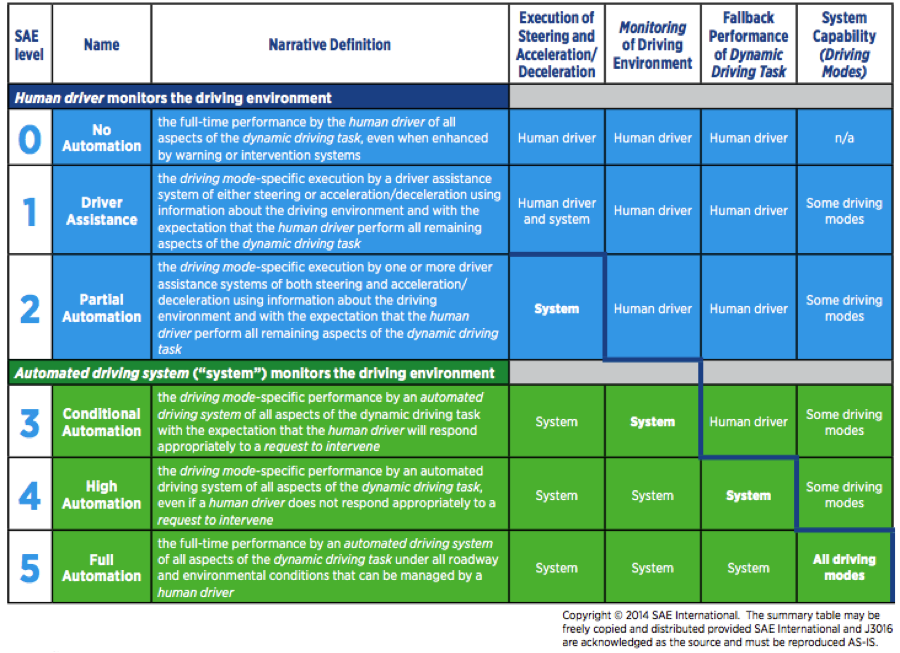

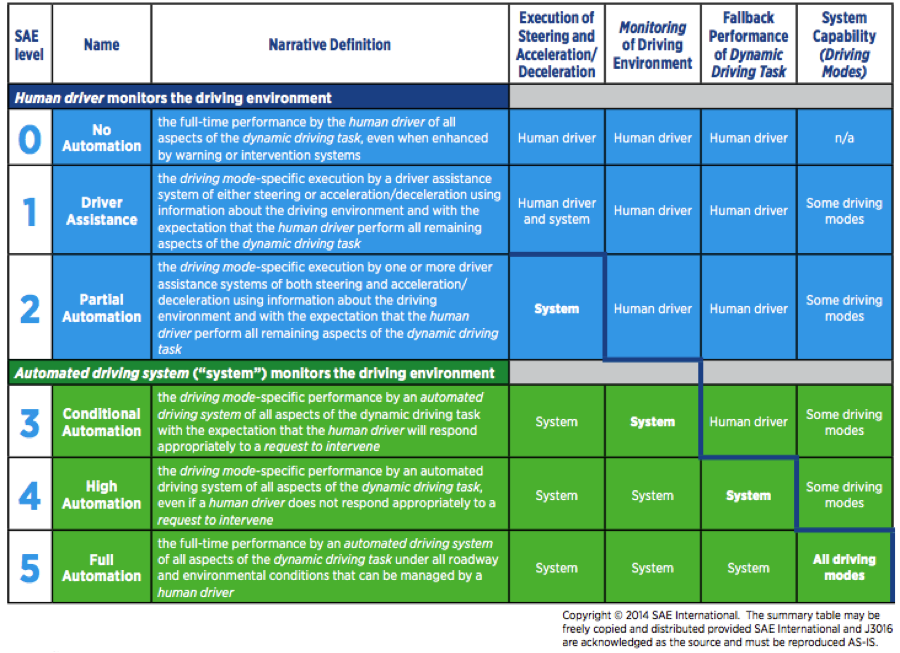

Uber’s testing vehicles straddle the line between being partially automated (SAE Level 2) or conditionally automated (SAE Level 3) since it can perform some functions, but test drivers must be immediately prepared to take over control at any time.

It appears that the human drivers are performing more dynamic driving tasks like parking or pulling over to pick up passengers and must monitor the driving environment at all times while keeping their hands near the steering wheel.

This suggests the system is not truly automated. Instead, it is an advanced driver assistance system similar to Tesla’s Autopilot, which is not restricted in the same way in California, or subject to the same regulations.

Compliance notwithstanding, Uber’s larger argument echoes others in the industry. The lack of consistent regulations for the testing and deployment of AVs has resulted in different regulatory challenges in every city and state – hampering its ability to freely test the technology.

“But there is a more fundamental point—how and when companies should be able to engineer and operate self-driving technology. We have seen different approaches to this question. Most states see the potential benefits, especially when it comes to road safety. And several cities and states have recognized that complex rules and requirements could have the unintended consequence of slowing innovation. Pittsburgh, Arizona, Nevada and Florida in particular have been leaders in this way, and by doing so have made clear that they are pro technology.”

In a non-binding policy statement released this September, the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) began the process of alleviating these barriers by suggesting a national framework for manufacturers to ensure the safety of autonomous vehicles while urging states to avoid creating a patchwork of prohibitive regulations.

However, until NHTSA takes the lead with binding actions or formal federal regulations, this is likely to be a recurring story.