Mass transit agencies across the country spent $2.3 billion of their CARES Act coronavirus funding in July, while airports spent $652 million of theirs, according to new reporting from the Office of Management and Budget. That still left $16.7 billion of the $25 billion in CARES Act transit aid and $8.4 billion of the $10 billion in CARES airport aid unspent as of July 31.

Every major airline, meanwhile, had spent 100 percent of its CARES funding by July 31, with smaller air carriers and contractors having $5.8 billion still unspent.

The updated reporting at usaspending.gov is browsable by department or account and shows every single grant or payment made using funding from the CARES Act or the other three COVID-19 relief bills passed by Congress this year.

| Recipient |

Total Appropriation |

Obligated by July 31 |

Outlaid by July 31 |

| Air carriers and contractors |

$32,000,000,000 |

$27,181,924,545 |

$26,223,911,370 |

| Mass transit providers |

$25,000,000,000 |

$21,519,433.523 |

$8,286,147,953 |

| Airports |

$10,000,000,000 |

$8,751,826,627 |

$1,582,845,826 |

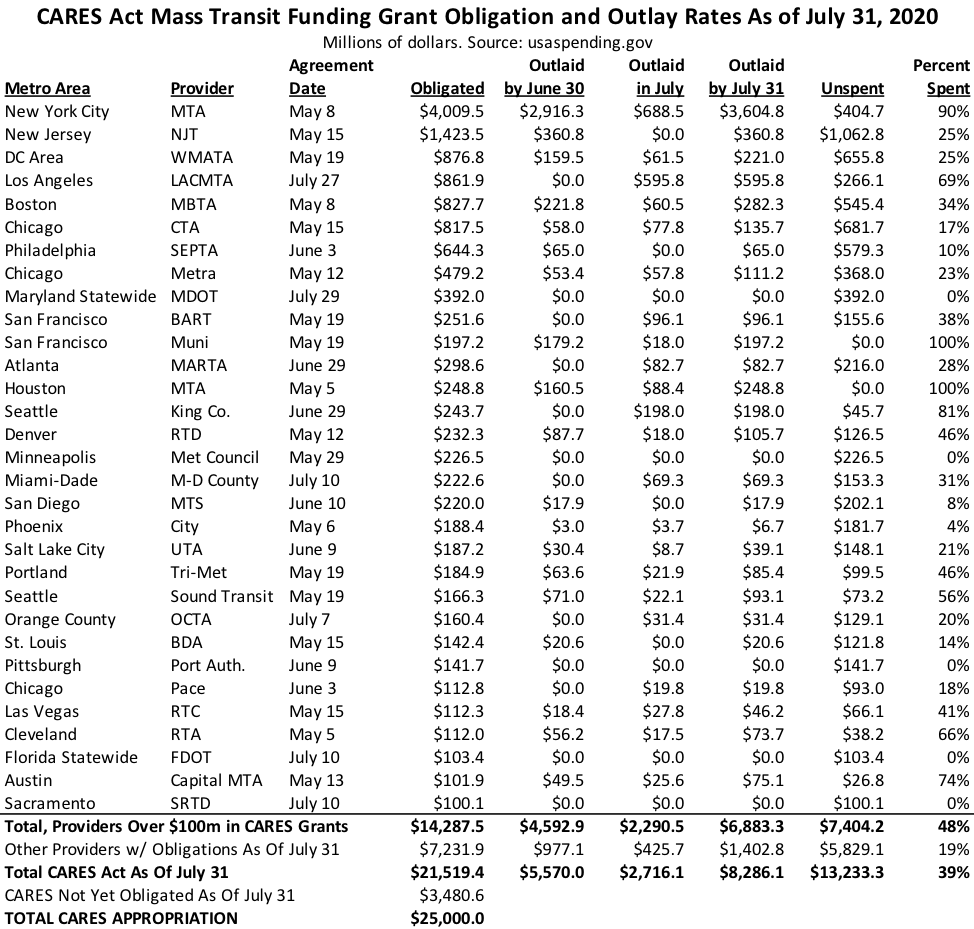

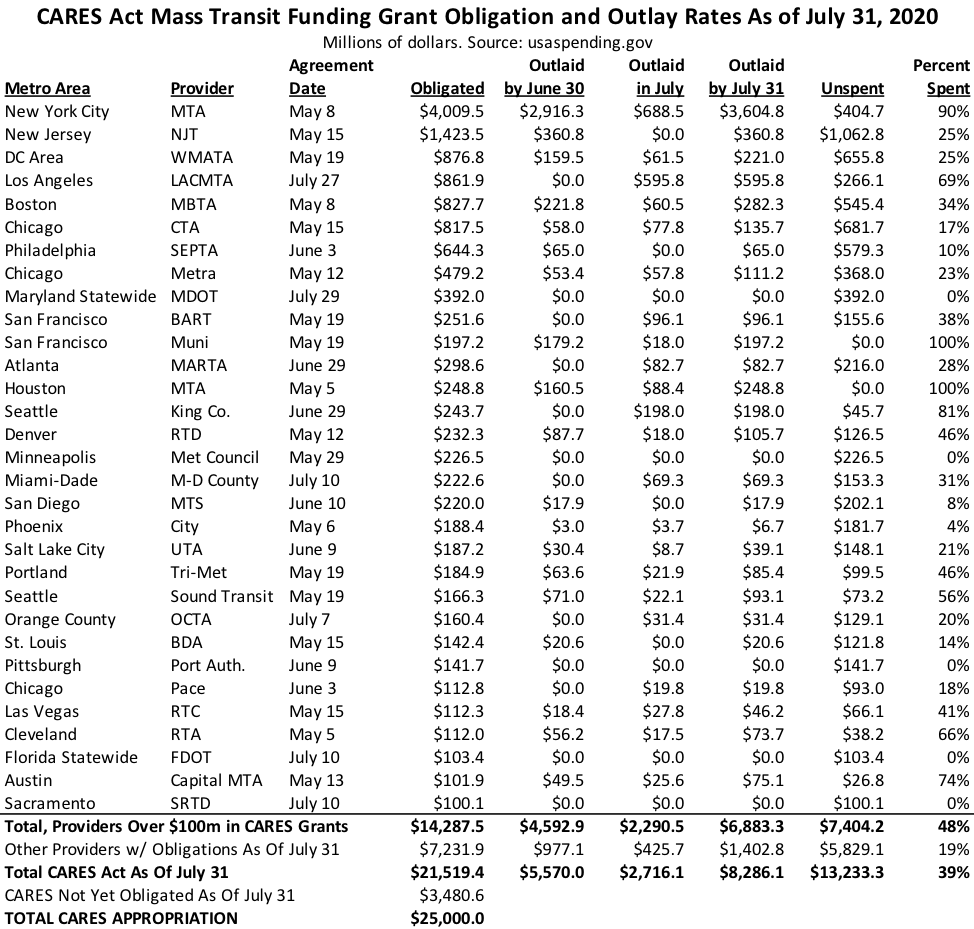

Mass transit. The data shows a huge discrepancy between the rate at which most big-city transit providers are spending their CARES money and the rate at which small providers are spending their money. As of July 31, Harris County, Texas (Houston) and San Francisco Muni had spent all of their CARES allotments, while New York City MTA had spent 90 percent and King County, Washington (Seattle) had spent 81 percent. (New York City announced in August that they had spent all of their CARES money.)

Looking at individual providers, the date on which the transit agency signed their grant agreement with the Federal Transit Administration, which legally obligates their funding that was announced on April 2. Some providers took longer than others to negotiate their grant agreements, and in some instances that was because the recipient then had to pass money through to other providers in their area. Los Angeles County, for example, did not get its agreement signed and its funding obligated until July 27, but once they did, they managed to spend $596 million of their $862 million grant in just four days. (Presumably, much of that was the pass-through funding.)

Other agencies that did not get their grant agreements signed until the July reporting period included Maryland and Florida statewide, Miami-Dade, Florida, Orange County, California, and Sacramento, California.

Then there are outliers like Minneapolis (May 29), Phoenix (May 6), San Diego (June 10) and Pittsburgh (June 9) who had still spent less than ten percent of their CARES funding (in some cases, zero dollars spent) as of July 31.

Some of these may have adopted budgets that plan on doling out their CARES funding throughout the fiscal year that started on July 1. For example, WMATA said this week that it is using its CARES money at a steady rate that looks to run out in December or January.

Large providers are definitely spending faster than small providers. Transit agencies with CARES grants of $100 million or more had negotiated $14.3 billion in grants as of July 31 and spent a little less than half of it ($6.8 billion), a spendout rate of 48 percent by July 31. All of the other transit providers in the country who had negotiated their grants by July 31 received a total of $7.2 billion, and they had only spent $1.4 billion of that sum (19 percent) as of July 31.

In addition, as of July 31, $3.5 billion of CARES transit funding had not yet been obligated. After the $75 million oversight set-aside, this means that transit agencies (mostly small ones) had not yet finished signing their grant agreements for $3.4 billion of the funding.

The total of the $25.0 billion appropriation that had been spent as of July 31 was 33 percent.

What does it mean that some providers (NYC MTA, San Fran Muni, Harris County) had already spent the entirety of their CARES dollars by mid-August, while other providers who are collectively entitled to $3.4 billion in CARES money had not even finished negotiating their grant agreements by July 31?

It might mean that every transit provider is different, and they have different blends of revenue sources and differing spend rates. Accordingly, maybe using the standard funding formulas that are used to distribute non-emergency money isn’t the best way to distribute emergency money. As much as it pains Congress to give out mass amounts of money without knowing for certain where the money will go, the best course of action for any future COVID relief might be to avoid using old formulas for funding distribution and trust the Department of Transportation to give out money on a “demonstrated need” basis, as originally proposed by the American Public Transportation Association back in May.

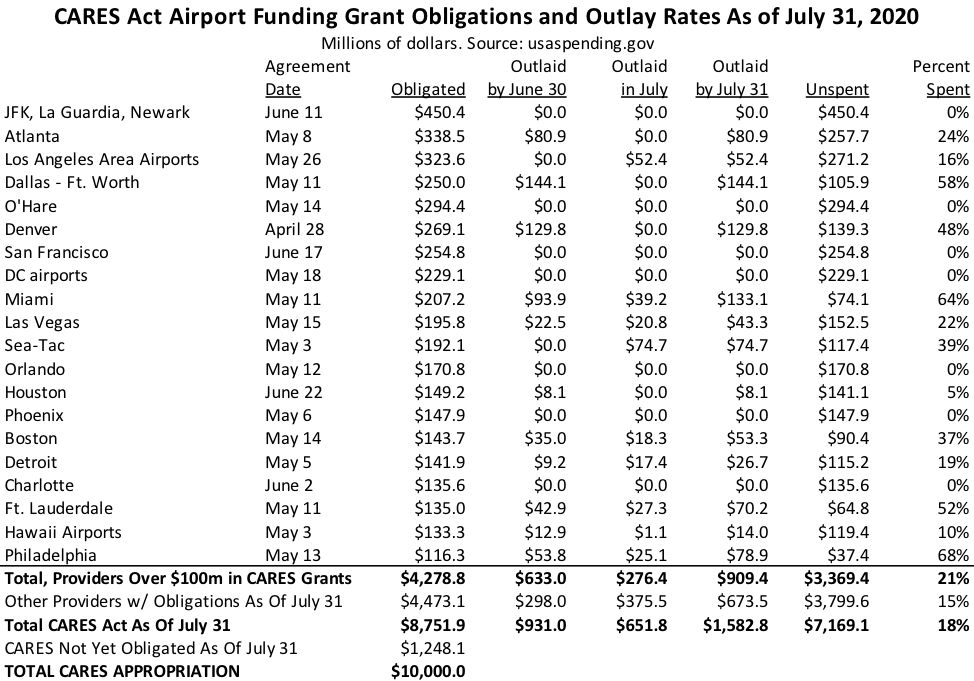

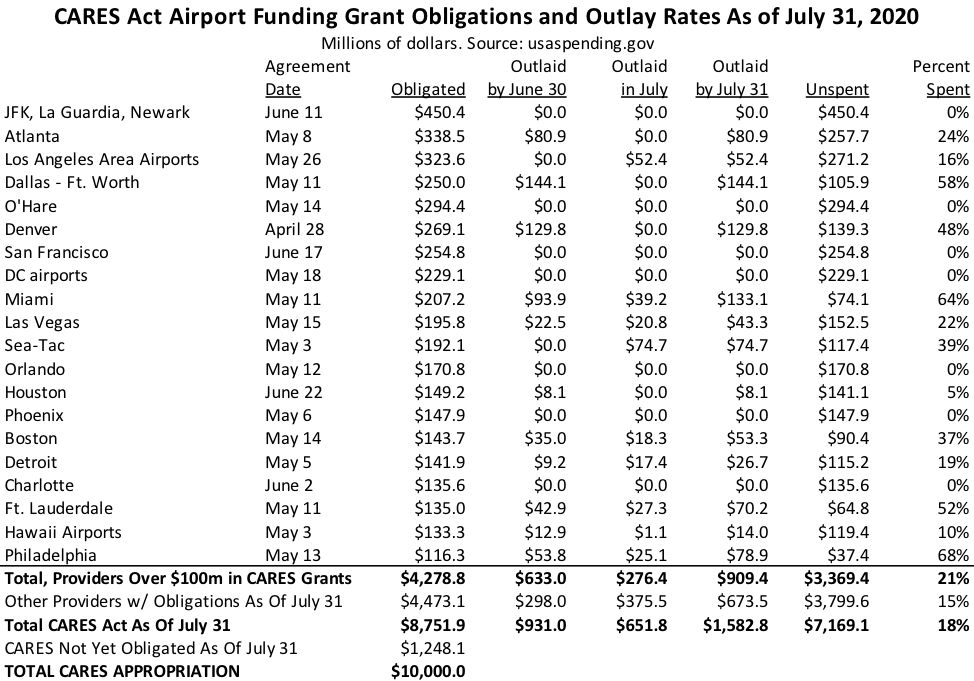

The following table shows the status, as of July 31, of all negotiated CARES grants to transit providers exceeding $100 million.

(The smallest mass transit CARES grant that had been negotiated and signed by July 31, per the website: the Nome, Alaska Eskimo Community. Grant award: $3,497. Three thousand, four hundred and ninety-seven dollars.)

Airports. The disparity between the spending rates of recipients of large CARES grants versus small CARES grants is not as great when it comes to airports. Airport authorities who had received grants of $100 million or more by July 31 had spent 21 percent of their money by that point, whereas all the other airports with smaller grants received by July 31 had spent 15 percent of their funding.

Big airports have much higher operating costs than small airports, of course, but they also have much bigger debt burdens, particularly debt secured by passenger facility charge (PFC) receipts, which are completely dependent on the number of passengers enplaning each day. The big argument as to why airports needed a special bailout in the CARES Act was that they had fixed debt service costs coming due eventually, and without passengers, they would default on that debt, which not only harms the airport but would make life rough in the municipal bond market.

The catch is that if an airport is going to spend its CARES money on debt service, it can’t actually spend that money until the note or interest payment comes due – quarterly, semiannually, whatever.

The total of the $10.0 billion appropriation that had been spent as of July 31 was 16 percent.