(Clicking on hyperlinks in the text will take you to original source documents, many of which are from the Eisenhower Library or other National Archives facilities and have never before been available online.)

Rapid decline of commuter rail

The late 1950s were a pivotal time for mass transit in urban areas – but, in part, that was due to the consequences of the 1958 railroad aid law (a law which was discussed in this article). As transit policy historian George Smerk wrote, “…legislation aimed at helping the railroads had become the vehicle for a major threat to the commuter rail portion of urban mass transportation. At least one of the consequences of the 1958 Act was unexpected – it sparked the advent of federal policy in urban mass transportation.”[1]

Smerk noted that the day President Eisenhower signed the 1958 bill into law, the New York Central issued a notice of abandonment for its commuter service to the west side of Manhattan, and other railroads immediately followed suit in major urban areas around the country.

The American Municipal Association published a major study in late 1959 of the transit needs of five major cities (New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston and Cleveland) comprising 18.5 percent of the U.S. population. The study found that if 25 percent of those now riding mass transit lines in those cities were to switch to automobiles, $4.5 billion in extra highway capacity would be needed, and if commuter railroads ceased altogether, the cost for new highways would rise to $17.4 billion.[2]

In early 1960, a group of big-city mayors and railroad executives came to Washington to promote a bill they had drafted to create a new government-owned corporation within the Commerce Department to make up to $1 billion in low-interest, 50-year loans to states and municipalities to purchase, maintain, or improve mass transit equipment and facilities.

Eisenhower’s Budget Bureau opposed the mayors’ bill, writing that “The Federal government should avoid new subsidies, including loans with subsidized interest rates, but might provide more latitude in the use of existing urban highway grants as an aid to meeting mass transportation needs” and preferring to modify existing rail and public facility loan programs, if necessary.[3]

That bill never advanced, but a similar bill from Sen. Harrison Williams (D-NJ) to allow the Housing and Home Finance Agency to make up to $100 million in similar loans did. The Commerce Department opposed the bill, stating that “The Department takes the position that the mass transit problem is basically one for cooperation between the communities involved and the carriers, whether publicly or privately owned.”[4]

And HHFA also opposed the bill, saying “To make Federal funds available for transportation loans at the subsidy interest rate provided in the bill would result, in fact, in virtually complete concentration of such loans in the Federal Government, and would also make them impossible to resell without great loss. It would be unreasonable, of course, to require the Federal Government to provide the necessary financing for all the proposed transportation systems and improvements throughout the United States. To do so would certainly require funds out of all proportion to the $100 million proposed to be authorized for this program.”[5]

The Williams bill passed the Senate by voice vote, but Administration opposition, the calendar, and the anti-urban bent of the House of Representatives at the time meant that the bill never came up for a vote there. It would be President Kennedy who began a national program of mass transit aid to cities.

Reactions to urban and metropolitan growth

The problem wasn’t that Eisenhower was unaware of urban transportation issues – far from it. In May 1959, the President and his brother Milton sat down with speechwriters to plot out a strategy for series of major addresses to take place over the final eighteen months of the Administration. An economic speech set for winter 1960 was to include discussion of “deficiencies in our transportation – our highways – our airways – waterways, what we are doing about them and what we need to do, to meet the pressing problems in what may very likely be the most urgent problem of rising urbanism.”[6] (The speech was never given.)

While Eisenhower’s public works czar, John S. Bragdon, was notable for how many internal battles he lost while the Administration’s highway program was being developed, he had success as an evangelist for comprehensive planning of public works at all levels of government. As far back as 1956, he advocated “Encouraging ‘Special Metropolitan Governments’ to establish comprehensive planning units for public works in metropolitan areas – what are called metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) today.[7]

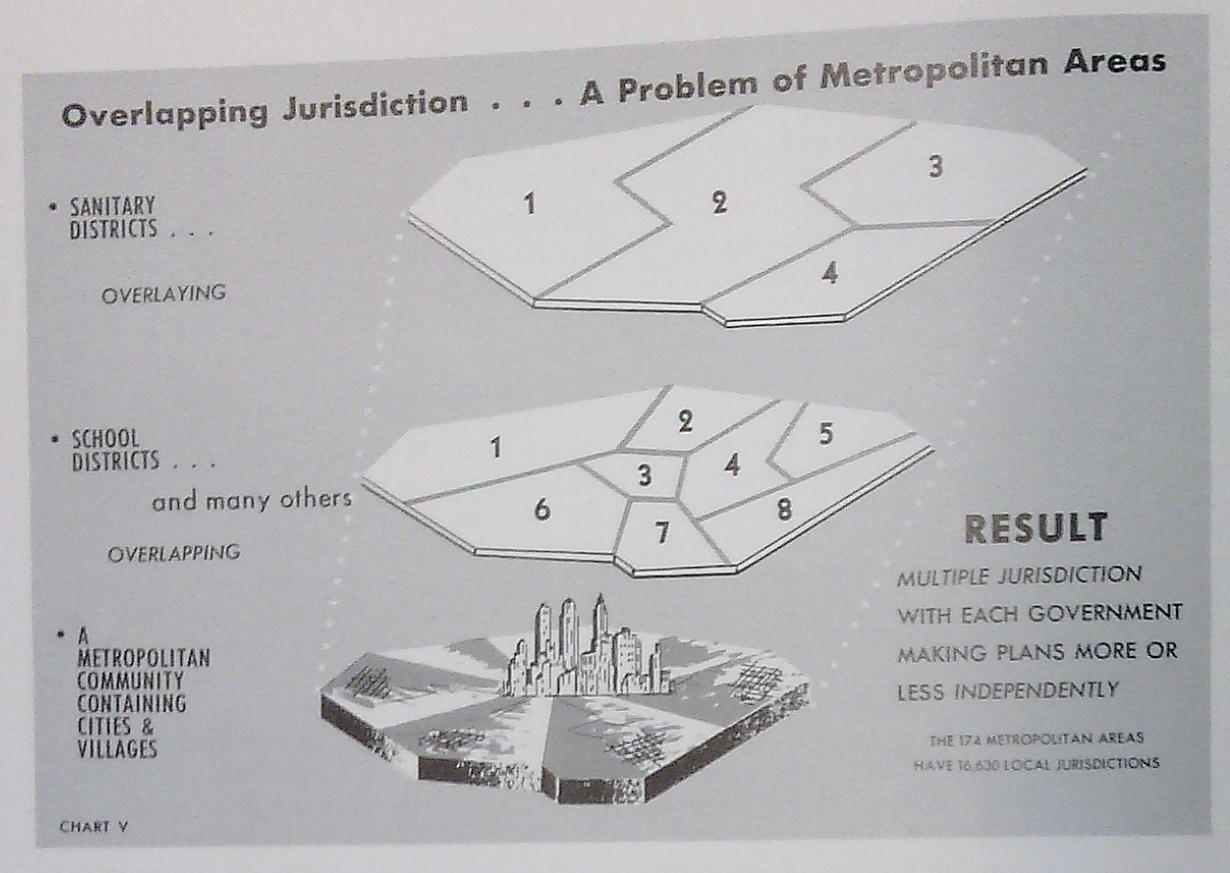

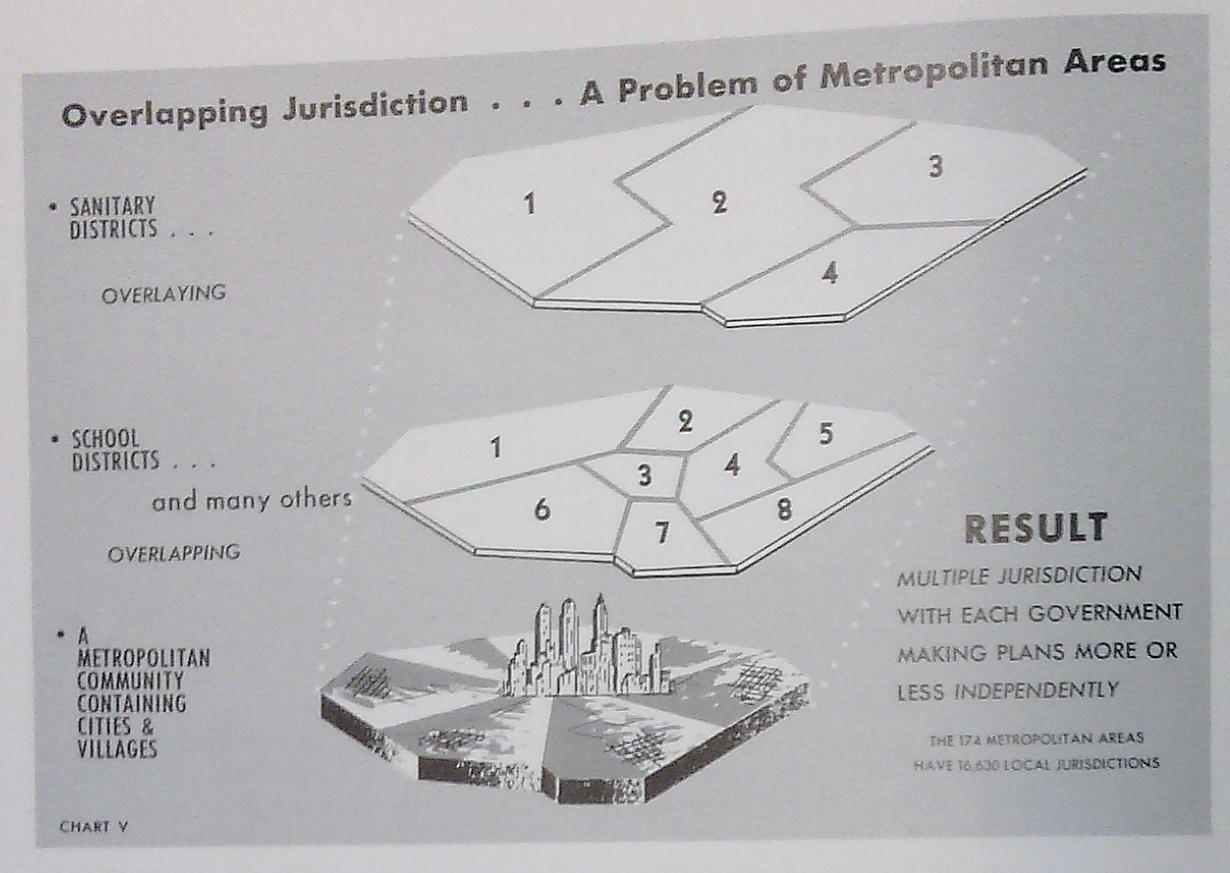

One of the charts used by Eisenhower aide John S. Bragdon to illustrate the need for comprehensive metropolitan area planning, 1957.

Also in late 1956, Bureau of the Budget staffer Robert Merriam proposed the creation of an Administration ad hoc committee on the problems of metropolitan areas.[8] Such a committee was established in 1957, and the minutes of its meetings show significant movement towards a more balanced federal role in letting metropolitan areas prioritize their own needs and allowing the federal government to deal directly with metropolitan areas. But the clock ran out on the Eisenhower Administration before much of that could be put into action.

The ad hoc committee had decided on a number of recommendations by December 1960, summarized in a white paper which Merriam then forwarded to the incoming Kennedy transition team in January 1961.[9] The white paper had several suggestions, but Merriam’s letter noted that the one that was already in effect was a new joint policy between the Public Roads Administration and the Housing and Home Finance Administration (appended to the end of the white paper) allowing state highway planning funds and urban planning grants from HHFA to be pooled for comprehensive planning in metropolitan areas.[10]

The Kennedy Administration would build upon this work with the requirement for all metropolitan areas to conduct balanced transportation planning in section 9 of the 1962 highway law (76 Stat. 1145). (Eisenhower’s planning advocate Bragdon went to work for the House Public Works Committee in 1961, where he also advocated for the planning provision in that bill.)

A subway for Washington, DC

As with airport aid, Eisenhower realized that the federal government had a special duty for the local affairs of the District of Columbia, and mass transit was no exception. Eisenhower pocket vetoed a bill in September 1954 that would have created a joint Maryland transit regulatory agency between D.C. and its two adjoining Maryland counties because, he said, it did not include Northern Virginia.[11] But Eisenhower supported the other provision of the bill, which required more study of D.C.’s mass transit problems.

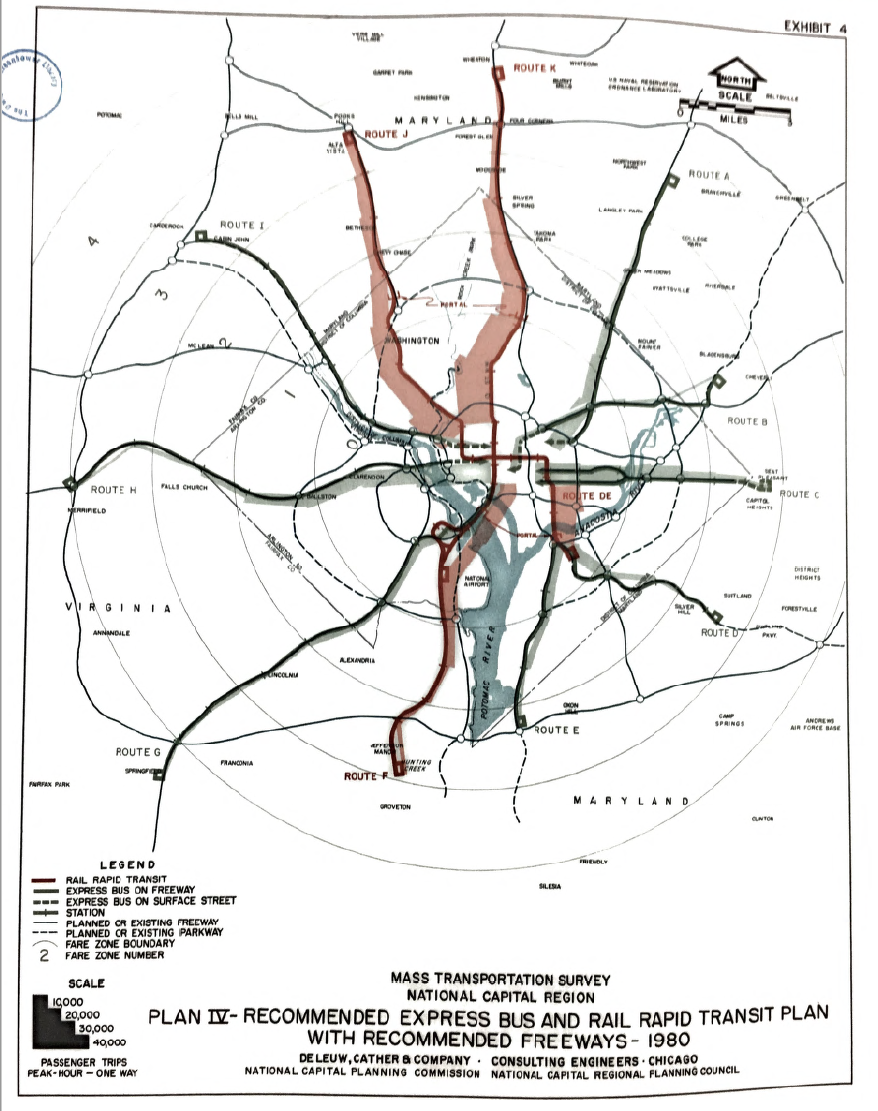

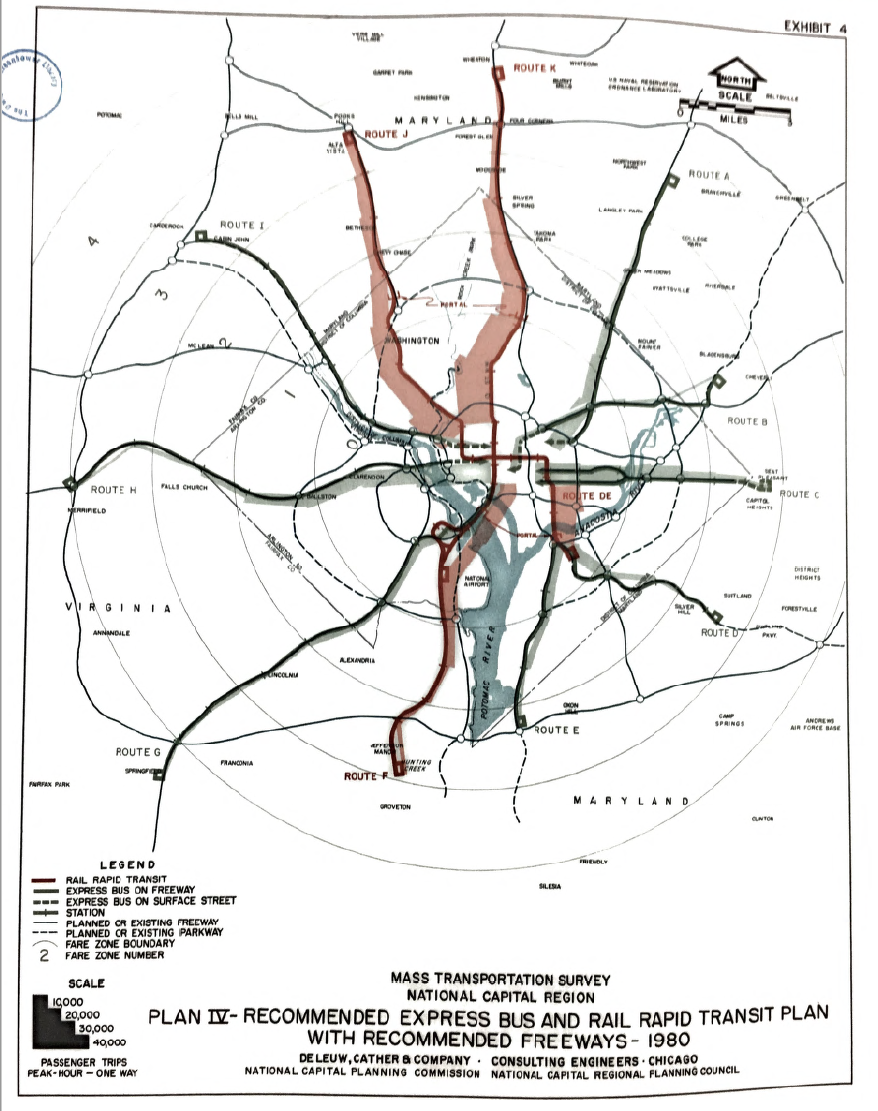

Early in the next session of Congress, Eisenhower signed an appropriations bill into law (69 Stat. 28) that funded a “survey of the present and future mass transportation needs of the National Capital region.”[12] That survey was delivered to Eisenhower in July 1959, and recommended construction of a new 34-mile, 36 station, $459 million subway system for the District, with a $31 million system of express buses to be operated while the system was under construction, deemed sufficient (with additional freeway construction) to serve the needs of the area through 1980.[13]

The recommended 1959 plan for rail rapid transit, express bus systems, and new freeways for the Washington DC area.

When presented with the survey, Eisenhower showed himself to be a conceptual pioneer of congestion pricing, asking “whether the committee had considered the possibility of a special tax on automobiles coming into the central areas of cities, it being his observation that it was very wasteful to have an average of just over one man per $3,000 car driving into the central area and taking all the space required to park the car.”[14]

After due study and interagency review, the White House (through the Bureau of the Budget’s Deputy Director) endorsed the plan at a Congressional hearing in November 1959, calling it “on the whole, a very excellent plan” and asking for the enactment of a bill creating a new temporary federal corporation to build the system and Congressional ratification of an interstate compact between the District, Maryland, and Virginia to eventually run the system.[15]

The White House sent the bill creating the National Capital Transportation Agency to Congress in mid-March 1960, and signed it into law (74 Stat. 537) in mid-July. That law also authorized D.C., Maryland, and Virginia to enter into an interstate compact to operate the transit system, but it took until 1966 for such a compact to be negotiated. Meanwhile, the plans for a transit system expanded greatly under President Kennedy, which led to delays in the beginning of construction.

Urban Interstates and the “Freeway Revolt”

Part of the delay in the eventual construction of the D.C. subway system was a local revolt against the construction of new Interstate highway routes across the District. Such revolts which were also happening in several other cities across the U.S., and herein lies one of the fundamental mysteries of Eisenhower transportation policy. At the July 1959 meeting where he was presented with the D.C. transit plan, Eisenhower “stated his concern that too much of the interstate highway money might be going into connections in the cities. He said that it was not his understanding that the Federal Government would pay 90 percent of these connections.”[16]

Between the urban extensions and the new cost estimate for Interstate construction (up from $27 billion in 1956 to $41 billion as of mid-1959), Eisenhower commissioned his public works czar, Stewart Bragdon, to perform a study of the highway program, with an emphasis on the urban extensions. In November 1959, Eisenhower told Bragdon that (according to Bragdon), “his idea had always been that the transcontinental network for interstate and intercity travel and the Defense significances are paramount and that routing within cities is primarily the responsibility of cities. The President was forceful on this point.”[17]

Things came to a head in April 1960, when the President met with Bragdon, the Secretary of Commerce, and the head of the Bureau of Public Roads. Bragdon brought his “First Interim Report,” a 103-page tome urging that the Interstate system be refocused on “an intercity, interregional, interstate highway systems” and that “other pressing needs be lme by local means or urban Federal-aid funds.”[18] He also wanted any urban Interstate segments to be “developed as a part of the area’s economic growth and land use plan, that as soon as possible the formulation of substantial, adequate economic growth and transportation plans be made prerequisite to the adoption of the highway plan.”[19] (Bragdon’s report also advocated new toll roads, because he always advocated new toll roads.)

Public Roads came to the meeting armed with a six-page analysis (more to Eisenhower’s attention span in meetings), “Memorandum on the Interstate System in Urban Areas,” which traced the origins of the Interstate back to the “Toll Roads and Free Roads” report of 1939, which called for “express routes into the center of the cities,” and the 1944 “Interregional Highways” report, which called for “adequate routes directly into the larger cities.”[20]

At the meeting, Eisenhower said he had never seen the Yellow Book of urban Interstate maps before, and the subsequent discussion of the urban Interstate extensions is so remarkable it needs to be quoted at length (again, from Bragdon’s recollection):

The President went on to say that the staff had also advised him that in the course of the legislation through the Congress, the point had been made that cities were to get adequate consideration on a ‘per person’ basis in view of the taxes they paid; in fact, that they were to get more consideration since they paid much more in taxes per person and in total than persons in rural areas.

The President added that this was what the Congress had been told, and that he was given to understand that this, together with the descriptions in the Yellow Book which they had before them when considering the legislation, were the prime reasons the Congress passed the Interstate Highway Act. In other words, the Yellow Book depicting routes in cities had sold the program in Congress…

He went on to say that the matter of running Interstate routes through the congested parts of the cities was entirely against his original concept and wishes; that he never anticipated that the program would turn out this way. He pointed out that when the Clay Committee Report was rendered, he had studied it carefully, and that he was certainly not aware of any concept of using the program to build up an extensive intra-city route network as part of the program he sponsored. He added that those who had not advised him that such was being done, and those who had steered the program in such a direction, had not followed his wishes.[21]

Bragdon said that at the end of the April 1960 meeting, Eisenhower “reiterated his disappointment over the way the program had been developed against his wishes, and that it had reached the point where his hands were virtually tied.”[22]

However, Bragdon may not have been a completely reliable narrator. Bertram Tallamy, from Public Roads, was also in that meeting, and later told interviewer Paul Mertz that it went down this way:

Tallamy: We had the meeting in the President’s Office. I was defending what we were doing, obviously, and Bragdon had an easel there with a lot of display charts with some young officer operating the charts for him, and he started the discussion and continued at quite some length. Then, I think, the President interrupted him and said “I’d like to hear what Mr. Tallamy has to say.” I could see that the President was getting nervous about the time he was spending on this, probably to him, minor detail. So I didn’t want to spend any more time than was absolutely necessary so I said, “Mr. President, I would like to show you this book which was on everybody’s desk at the time the Interstate legislation was approved.”

Mertz: This was the “yellow book”?”

Tallamy: Yes. Then I leafed through and showed a couple of charts showing the cities and said, “These are the routes in them.” He said, “Are you sure? This was on everybody’s desk?” I said, “Well I’m pretty sure. I wasn’t there at the time, but I am as certain as can be that that was the case.” I’m not sure of this, but pretty sure, he turned and asked General Bragdon if that was his recollection too, and I am quite sure he said it was. Well then, I think the President said “I didn’t realize that that was the case”–something to that effect. Then he said, “The meeting’s over gentlemen, I’ll let you know what I decide.” This is the way it ended.[23]

Tallamy’s recollection is consistent with what William Ewald, Eisenhower’s research assistant and ghostwriter on his White House memoirs, remembers about Eisenhower’s general practice: “to Eisenhower, the written word was the final arbiter.”[24] Ewald says that whenever Eisenhower’s memory was challenged by a contemporary written record, Eisenhower admitted that his memory must have been wrong.

(Tallamy’s memory also seems right on the charts – Bragdon had prepared 27 pages of double-spaced text to read while presenting his charts, and his notes show he only got through 24 of them before Eisenhower lost patience.)

How could something so important have escaped Eisenhower’s notice for almost five years? The calendar may have had something to do with it. The date in the Yellow Book indicates that the Commissioner of Public Roads gave his formal approval to the maps of the urban extensions on September 15, 1955, and the maps were then published by GPO and sent to Congress, presumably, a few weeks later.

After the 1955 session of Congress had ended, Eisenhower headed to Denver on August 14 for a planned six-week stay at his “Summer White House” there. On September 24, Eisenhower had a massive heart attack. The President’s appointment books show that Eisenhower was virtually incommunicado for the first two weeks of his recovery and was hospitalized, on light duty, in Denver until November 11, and then recuperated at his farm in Gettysburg for most of another month. During this time, Vice President Nixon presided over the regular Cabinet and National Security Council meetings, including ones on September 30 and October 28 when the highway program was discussed.

It is entirely possible that the selection of urban Interstate routes and the transmission of the Yellow Book to Congress just didn’t rise to the level of what the White House staff thought was important enough to raise with Eisenhower during his vacation in Denver and subsequent hospitalization.

The end result of the April 1960 meeting was a one-page memo from Eisenhower to the Commerce Secretary on April 11, directing no deletions of urban routes from the Yellow Book (but, when determining routes near smaller cities, “bypass routes and spurs are to be preferred to penetrating routes”), and also stating that “Solution of the rush hour traffic problems in metropolitan areas is not considered a function of the Interstate System.”[25]

The third meeting of the ad hoc Interagency Committee on Metropolitan Area Problems was held in June 1960, and the minutes of that meeting show its chairman, White House policy aide Robert Merriam, stating that “the President’s highway program has resulted in States and municipalities becoming highway-oriented, which is not surprising since nearly two-thirds of the remainder of this program, or $17 billion, will be spent in urban areas. The question naturally arises as to whether the Federal Government should permit the States to allocate these funds within urban areas in any one of several combinations, and perhaps even including their use for mass transit facilities.”[26]

Bragdon was all for the idea (though not at the 90 percent federal cost share being used for Interstate construction, which he found wasteful), and it was agreed that the committee would come up with a study on the relationship of the highway program to mass transit for possible mention in Eisenhower’s outgoing State of the Union address in January 1961.[27] The final paper produced by the committee was short on specific policy recommendations, though it did recognize that “a massive highway program may contribute to creating a local transit problem. Yet, current highway law and administration is so rigid as to prevent use of highway funds for local mass transit purposes or ordinarily even the provision of median strips on federally operated urban highways.”[28] And Eisenhower’s last State of the Union address generally eschewed proposals for the future.

However, resistance to some of the urban Interstate extensions was so great that in 1973, Congress would establish a program where some cities and states could withdraw certain segments from the Interstate highway map and instead receive an equivalent amount of federal funding for other roads – or for mass transit. The District of Columbia canceled almost $2 billion of its urban Interstates and used the money as its matching share to build its subway system. Sacramento, Chicago, Boston, Baltimore, New York City, Cleveland, Portland, and Philadelphia also made major investments in mass transit with repurposed Interstate highway funding.[29]

[1] George M. Smerk, The Federal Role in Urban Mass Transportation (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991) p. 61.

[2] American Municipal Association, The Collapse of Commuter Service: A Threat to the Survival of America’s Metropolitan Areas, 1959, p. 2.

[3] Bureau of the Budget Commerce and Finance (Reeve) to Deputy Director, memorandum entitled Administration position on proposed Mass Transit Financing Corporation Act, March 11, 1960. Find box/folder citation.

[4] Letter from Under Secretary of Commerce Philip A. Ray to Sen. A. Willis Robertson, May 31, 1959. Reprinted in U.S. Senate. Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. Housing Legislation of 1960 (Hearings on Various Bills to Amend the Federal Housing Laws), 86th Congress, 2nd Session, May 1960, pp. 1038-1039.

[5] Letter from HHFA Administrator Norman P. Mason to Sen. A. Willis Robertson, May 6, 1960. Reprinted in Housing Legislation of 1960, pp. 56-58.

[6] Malcolm Moos, Memorandum for The President and Dr. Milton Eisenhower, May 24, 1959. Located in Arthur Larson and Malcolm Moos Records, Box 17, folder entitled “Presidential Speech Planning,” Eisenhower Library.

[7] John S. Bragdon, “A New Concept in Public Works Planning,” November 15, 1956 p. 2. FIND CITATION

[8] Memorandum from Robert Merriam to Governor Howard Pyle, subject line “Creation of an ad hoc committee for Federal Government consideration of metropolitan problems” dated November 9, 1956. Located in Robert E. Merriam Records 1955-61, Box 1, Eisenhower Library.

[9] “Coordination of Federal Metropolitan Area Development Activities – December 19, 1960.” Located in Robert E. Merriam Records 1955-61, Box 1, Eisenhower Library.

[10] “Joint Policy and Procedural Statements on Improved Coordination of Highway and General Urban Planning – Revised November 23, 1960.” Located in Robert E. Merriam Records 1955-61, Box 1, Eisenhower Library.

[11] The bill was H.R. 2236 of the 83rd Congress. Veto message is in Congressional Record (bound edition), August 20, 1954, p. 15567.

[12] Public Law 24 of the 84th Congress, 69 Stat. 28, at 33.

[13] DeLeuw, Cather & Company. Mass Transportation Survey, National Capital Region – Civil Engineering Report. January 1959. Located in Robert E. Merriam Records 1955-61, Box 17, Eisenhower Library.

[14] Memorandum for the Record of July 13, 1959 meeting between the President and national capital area officials. Located in Robert E. Merriam Records 1955-61, Box 8, folder entitled “Mass Transportation Survey (1),” Eisenhower Library.

[15] Statement of Elmer B. Staats, printed in U.S. Congress. Joint Committee on Washington Metropolitan Problems. Transportation Plan for the National Capital Region (Hearings on the Report of the Washington Mass Transportation Survey, 86th Congress, 1st Session), November 1959, starting on p. 13.

[16] Memorandum for the Record of July 13, 1959 meeting, cited above.

[17] J.S. Bragdon. Memorandum for the Record – November 30, 1959. Located in DDE’s Papers as President, Ann Whitman File, Administrative Series, Box 7, folder entitled “Bragdon, John S. (1),” Eisenhower Library.

[18] “Progress Review and Analysis, Federal Highway Program – Interim Report, Prepared by the Special Assistant for Public Works Planning, March 1960.” p. 7. Original located in the Papers of John S. Bragdon, Eisenhower Library.

[19] Ibid p. 8.

[20] U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, “Memorandum on the Interstate System in Urban Areas.” Undated, but entered into White House files on April 7, 1960, and bearing a note that it was brought to the White House by Administrator Bert Tallamy. Original in

[21] J.S. Bragdon. Memorandum for the Record – Meeting in the President’s Office – Interim Report on the Interstate Highway Program – April 6, 1960, 10:35 a.m. Located in DDE’s Papers as President, Ann Whitman File, DDE Diary Series, Box 49, folder entitled “Staff Notes – April 1960 (2), Eisenhower Library.

[22] Bragdon Memo for the Record – April 6, 1960.

[23] Lee Mertz, “The Bragdon Committee.” Retrieved online from the Federal Highway Administration website on September 13, 2020 at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/bragdon.cfm

[24] William Bragg Ewald, Jr. Eisenhower the President, Crucial Days: 1951-1960. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1981 p. 102.

[25] Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Memorandum for the Secretary of Commerce,” April 11, 1960. Located in folder OF-141-B “Highways and Thoroughfares (Roads)(25) in Box 612 of the Official File series of Dwight D. Eisenhower: Records as President, White House Central Files, 1952-1961 in the Eisenhower Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[26] “Minutes of the Third Meeting of the ad hoc Interagency Committee on Metropolitan Area Problems,” p. 2. Located in Robert E. Merriam Records 1955-61, Box 1, Eisenhower Library.

[27] Ibid p. 4.

[28] Coordination of Federal Metropolitan Area Development Activities – December 19, 1960” p. 26.

[29] Federal Highway Administration. “The Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways: Part V – Interstate Withdrawal-Substitution Program.” Retrieved online on March 12, 2020 at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/highwayhistory/data/page05.cfm