Reorganizing DOT: What Can Be Done, and the 1995 Example

Transportation observers are anxiously awaiting the release of the Trump Administration’s reorganization plan for the U.S. Department of Transportation. The White House has ordered all departments, in cooperation with the “Department of Government Efficiency,” to come up with reorganization plans that will get rid of redundancies and reduce headcount. The Secretary of State outlined his plan this week, and HHS released their plan several weeks ago.

As we await a Transportation Department reorganization plan, it will be useful to take a quick look at how USDOT is organized, and a closer look at just how radical the Clinton Administration’s proposed reorganization plan was, 30 years ago this month.

How USDOT is organized. The “organic” statutes creating and sustaining the Department and its various modes are found in chapter 1 of title, United States Code, aptly entitled “Organization.” Section 102 establishes the Department, declares that it shall have a Secretary, Assistant Secretary, General Counsel, Under Secretary, and eight Assistant Secretaries (and gives them titles and some responsibilities), and also establishes an Office of Tribal Government Affairs, an Office of Climate Change and Environment, an Interagency Infrastructure Permitting Improvement Center, and a Chief Travel and Tourism Officer.

Sections 103 through 113 establish each of the various modal administrations within DOT, with varying degrees of specificity. Other DOT offices established in chapter 1 are the National Surface Transportation and Innovative Finance Bureau, the Council on Credit and Finance, the Office of Multimodal Freight Infrastructure and Policy, and the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure.

Anything listed in chapter 1 of title 49 is law, and would take another law to amend. The law gives some modal administrators more duties than others:

Then, there are thousands of pages of statutes throughout titles 49 (Transportation) and 23 (Highways) that give powers and prescribe duties, and almost all of those are given to the Secretary of Transportation, not to any modal administrator. The law (23 U.S.C. §104) gives the Secretary the job of apportioning highway money to states. Ditto for mass transit formula money (49 U.S.C. §5336).

But there aren’t enough hours in the day for the Secretary, or the Office of the Secretary, to carry out all these duties. Accordingly, we have Part 1 of Subtitle A of title 49 of the Code of Federal Regulations. Subpart B establishes offices and duties within OST gives duties to the Deputy, Under, and all the Assistant Secretaries. Part 1 then delegates a long list of the Secretary’s legal responsibilities to the modal administrators and OST officials.

For example, 49CFR§1.85 delegates to the FHWA Administrator the specific duties to carry out every highway law (and they are all listed therein). Ditto for the other modal administrators.

But the Secretary is free to change the delegations and authorities in Part 1 of title 49 CFR at any time, since they are simply regulations. (Unless they are duplicated in law in title 49, which some of them are.)

The “REGO” plan of 1995. In 1992, Bill Clinton and Al Gore, the first of the “New Democrats” to be national nominees, ran on a platform of “reinventing government” so as to be able to counter Ronald Reagan’s “government is the problem” line of attack. On March 3, 1993, Clinton announced that Gore would be in charge of a “National Performance Review” to suggest ways to make government more efficient and to issue its initial report within six months.

Clinton said “it’s time our Government adjusted to the real world, tightened its belt, managed its affairs in the context of an economy that is information based, rapidly changing, and puts a premium on speed and function and service, not rules and regulations.”

The “Phase I” report was released in September 1995. The specific USDOT recommendations including establishing a government-owned corporation outside the FAA to provide air traffic control, which did not happen, but also proposed these things that did get implemented: GARVEE bonds, FAA overflight fees, the contract tower program, and a variety of IT-related improvements.

Two months after the Phase I report was issued, the GOP won the midterm elections and took over both chambers of Congress, so Clinton and Gore figured there was a bigger market for wholesale change in government and ordered a Phase II.

For USDOT, the big REGO Phase II reorganization – previewed in the FY 1996 Budget in early February 1995 and then fleshed out with proposed legislation on April 6 – had two pieces. First, it reiterated the biggest chunk of the Phase I plan, whereby the biggest single piece of DOT – the air traffic control system administered by the Federal Aviation Administration – would be removed from government entirely and converted into a government-owned United States Air Traffic Service Corporation, to be self-funded by user fees charged to airlines and general aviation. (The bill was H.R. 1441, 104th Congress.)

Corporatization of air traffic control was not a new idea, but was based on a 1987 proposal by Senators Ted Stevens (R-AK) and Daniel Inouye (D-HI), which was in turn based on a bill dating all the way back to 1976. Congress ignored it then, they ignored it when Clinton and Gore proposed it in 1995, and despite the best efforts of chairman Bill Shuster (R-PA), they didn’t have the votes to pass something very similar when he championed it in 2015-2018.

Once air traffic control and its 33,000 employees were removed from the Department, the structure of what remained was to be vastly simplified. A FAA would remain as a separate modal administration within DOT, but focused only on safety, airport development, and civil aviation security. And the Coast Guard would remain as a separate modal administration within DOT, because you can’t split up the Guard due to the law requiring that the Guard, as a whole, be transferred to the Defense Department during time of war.

All the other modal administrations at DOT – FHWA, NHTSA, FTA, FRA, MARAD, and what then oversaw pipelines and hazmat, RSPA – would be combined into one Intermodal Transportation Administration. (The St. Lawrence Seaway would become another independent corporation outside DOT. And FMCSA did not exist in 1993 – it was still the Office of Motor Carriers within FHWA.) The bill implementing this part was H.R. 1440, 104th Congress.

On the organizational structure side, there were supposed to be two major areas of increased efficiency from this reorganization. The first was stripping each modal administration of its bureaucratic overhead and combining it all in an “Administrative Services Bureau” to support all modes. At the press conference announcing the plan in April 1996, Deputy Secretary Mort Downey was summarized thusly:

“Downey also addressed a key element in the plan’s target for reducing the department’s overhead by 50% , the creation of a DOT Administrative Services Bureau. The bureau will provide certain administrative services to the three operating administrations. After two years, the administrations will have the choice whether to continue the relationship, to assign additional personnel and functions to the bureau, to contract for these services with other private or public vendors, to provide them in-house, or even to stop the services altogether. Any option may be selected, so long as the 50 % target cost reduction is met.”

Here’s how it looked in an org chart that we at Eno published in our Summer 1995 issue of Transportation Quarterly:

A February 1995 GAO testimony showed potential redundancies in various offices that were duplicated across the modal administrations that were to be consolidated:

| FHWA | FTA | FRA | NHTSA | MARAD | Total | |

| Office of Administrator | 19 | 7 | 10 | 17 | 11 | 64 |

| Administration | 277 | 62 | 63 | 80 | 105 | 587 |

| Policy | 94 | 61 | 32 | 10 | 43 | 240 |

| Counsel | 38 | 23 | 41 | 8 | 42 | 152 |

| Civil Rights | 19 | 16 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 42 |

| Public Affairs | 7 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 36 |

| TOTAL STAFFING | 454 | 174 | 153 | 131 | 209 | 1,121 |

The other organizational savings was to come from the consolidation of the field offices of the various modal administrations. If Congress approved the reorganization of the modes to start on time in October 1995, then the press conference indicated: “During FY 1996, the reorganizational effort will focus on merging the headquarters operations of the modes in an orderly year- long process. Restructuring of field operations will occur in FY 1997 , after detailed study and consultation with Congress. The department proposes to spend a year studying how to reduce its network of 1,700 field offices. Currently, each mode divides the country differently, with inconsistent regional boundaries and separate offices.”

The GAO testimony included a map of all of the various DOT field offices, which could give the layman a sense of where consolidation might come:

It must be emphasized that the reduction of federal employee headcount was a major selling point of all the restructuring. Pena’s press release took pride in this: “Since Secretary Peña took office in 1993, the DOT has eliminated over 4,000 positions, resulting in annual savings of $260 million. Over the next five years , the department expects to realize a total of more than $1.5 billion in down-sizing savings, at least $ 500 million of which is directly attributable to the proposed reorganization. Significantly, the reorganization will enable the goals to be met without a decline in service.

“Including the off-payroll transfer of air traffic control employees under the separate legislation and an additional 7,000 other civilian and military DOT workers, the department’s 1995 workforce of 105,000 would be cut nearly 50%.”

However, removing the “stovepipes” on the organizational chart would be of limited usefulness unless the stovepiping was also removed on the program and funding side. Accordingly, the FY 1996 Budget also proposed to reorganize funding and programs along the new lines. The Highway Trust Fund and a downsized Airport and Airway Trust Fund would be combined into a single Transportation Trust Fund. (The excise taxes supporting the AATF would be reduced to compensate for no longer having to fund air traffic control.)

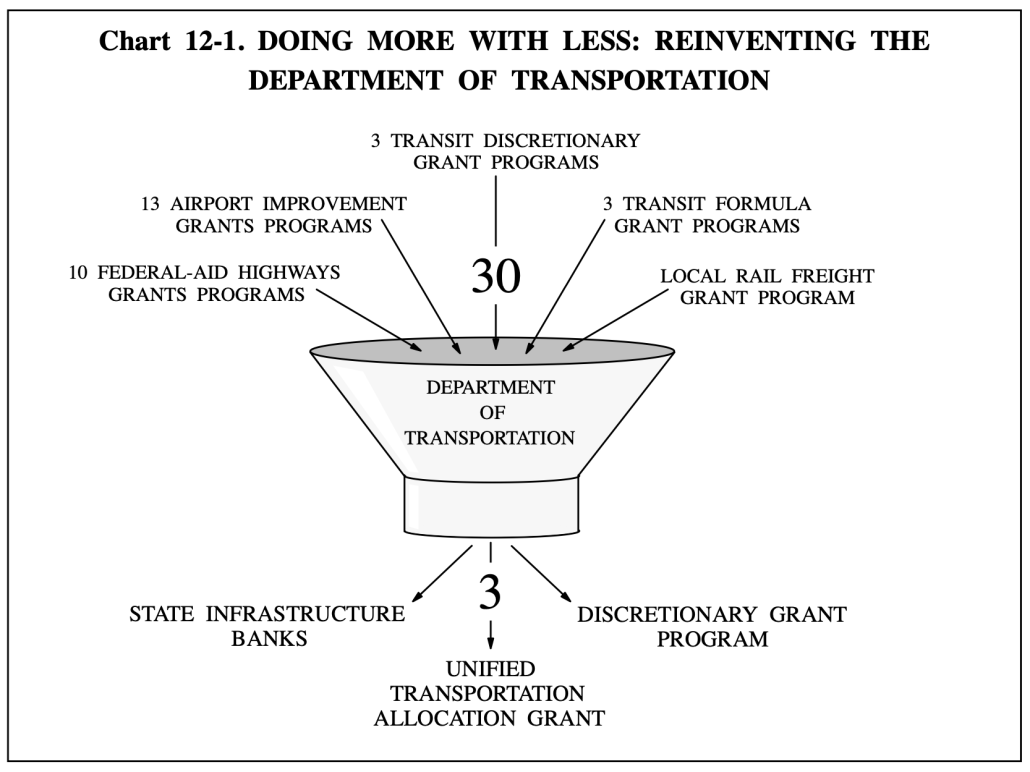

And almost all federal grant programs for infrastructure would be combined into a single Unified Transportation Infrastructure Investment Program (UTIIP), with three major components: a Unified Allocation for each state and locality from which they could prioritize any non-NHS highway project, any mass transit project, or any airport project; capitalization for State Infrastructure Banks to allow states access to stable long-term financing with federal assistance, and a discretionary fund for the Secretary to select projects.

The following table, taken from information submitted by Secretary Pena to the Senate Appropriations Committee, shows how the Clinton Administration proposed to use program consolidation to cut $2.3 billion in program spending from capital infrastructure grant programs.

| USDOT’s FY 1996 Unified Budget Proposal (Million $$) | ||||

| (Capital grants 0nly – excludes operating subsidies and admin/research.) | ||||

| FY 1995 | FY 1996 | |||

| National Capital Grant Programs | ||||

| FHWA | Federal-aid Highways | 19,224 | ||

| FAA | Airport grants | 1,450 | ||

| FTA | Formula Grants | 1,790 | ||

| FTA | Discretionary Grants | 1,725 | ||

| Highway earmark, airport LOI, & transit FFGA | 1,143 | |||

| UTIIP | Unified allocation grant | 10,000 | ||

| UTIIP | State Infrastructure Banks | 2,000 | ||

| UTIIP | Discretionary grants | 1,000 | ||

| UTIIP | Interstate/NHS | 7,361 | ||

| UTIIP | Federal lands highways | 442 | ||

| Subtotal, existing vs UTIIP replacement | 24,189 | 21,946 | ||

| Other Capital Grant Programs | ||||

| FTA | Grants to WMATA | 200 | 200 | |

| FTA | Interstate Transfer Grants | 48 | ||

| FRA | Amtrak (Capital) | 230 | 330 | |

| FRA | Northeast Corridor Improvement | 200 | 235 | |

| FRA | Penn Station Redevelopment | 40 | 50 | |

| FRA | Rhode Island Rail | 5 | 10 | |

| FRA | Local Freight Rail Assistance | 17 | ||

| Subtotal, Other Capital Grant Programs | 740 | 825 | ||

| Direct Federal Physical Capital | ||||

| FAA | Facilities and Equipment | 1,879 | 1,701 | |

| USCG | Acquis., Construct, & Improve. | 319 | 380 | |

| USCG | Alteration of Bridges | 2 | ||

| MARAD | Title XI Loan Program | 52 | 52 | |

| TOTAL CAPITAL PROGRAM | 27,179 | 24,905 | ||

| Difference | -2,274 | |||

($1.1 billion in FY 1996 money was to be obligated for prior-year commitments like ISTEA highway earmarks, mass transit full funding grant agreement (FFGA) installments, and airport grant letters of intent. And the table excludes $420 million in Amtrak operating subsidies, $500 million in mass transit operating assistance, and $263 million in R&D and administrative expenses in 1996 and an unknown amount for those in 1995.)

Both the proposed organizational changes and the program and funding changes faced inevitable resistance on Capitol Hill due to committee jurisdictional issues and stakeholder resistance. But there were other problems:

- Stakeholders and Congress were not in a mood to cut $2.3 billion in funding. To the contrary – 1996 was the year that Highway Trust Fund tax receipts were scheduled to increase by $2.2 billion (+10 percent) because the final 2.5 cents of the 5 cent-per-gallon motor fuels tax increase from the 1990 deficit reduction deal were scheduled to be transferred from the General Fund to the Trust Fund, meaning that Congress and stakeholders expected to be able to spend that money.

- The proposal could be viewed as a sneaky way to transfer the burden of $750 million per year in Amtrak funding from general revenues to highway users, which always drew visceral opposition from highway stakeholder groups.

- On the program side, the timing of Gore’s REGO was just off. This proposal was partway through the multi-year ISTEA surface transportation funding bill’s duration. With Congress due to do a complete rewrite of these programs in 1997, upon the expiration of ISTEA, no one was in a mood to reinvent the wheel before they had to. As a matter of political inertia, it is usually impossible to reopen one of those bills halfway through because that would mean partially undoing all of the funding deals and tradeoffs that were necessary to get the votes to pass the original bill. When the Clinton Administration submitted its formal ISTEA reauthorization proposal, NEXTEA, in March 1997, it included little of the REGO proposal.

Congress took no action on the DOT restricting or on the air traffic control corporatization (although a third part of transportation reorganization, outside of DOT, made it into law – the abolition of the Interstate Commerce Commission). The consolidation of field offices made enough sense that DOT established a “Colocation Task Force” in June 1996, but a GAO report two years later said the task force had made little progress.

For more information on the 1995 DOT reorganization proposal, see the following articles from Eno’s Transportation Quarterly:

Winter 1995 issue – “A Surface Transportation Agency: The Time Has Come” by E. Dean Carlson.

Summer 1995 issue – “Implications of the USDOT Restructuring” by Gene C. Griffin.

Summer 1995 issue – “Downey on the USDOT Reorganization” (interview with Deputy Transportation Secretary Mort Downey).