October 25, 2018

Last week I was invited to speak at and participate in the Minnesota-Wisconsin Public Transportation Conference and Expo in La Crosse, WI. Transit agencies in attendance ranged from Metro Transit in the Twin Cities region to dozens of small, rural providers from both states. Each size and shape of agency has its own challenges and problems, but a few underlying themes kept emerging throughout the conference.

All face financial challenges, which routinely came up during sessions. Because most agencies only expect little, if any, new federal money, attendees turned the conversations toward innovative ways to seek funding from voters, local councils, and their state governments. They also want to innovate and provide attractive, modern service to compete in the full mobility market. Multiple conversations revolved around “on-demand” and “flexible” transit to meet changing rider expectations.

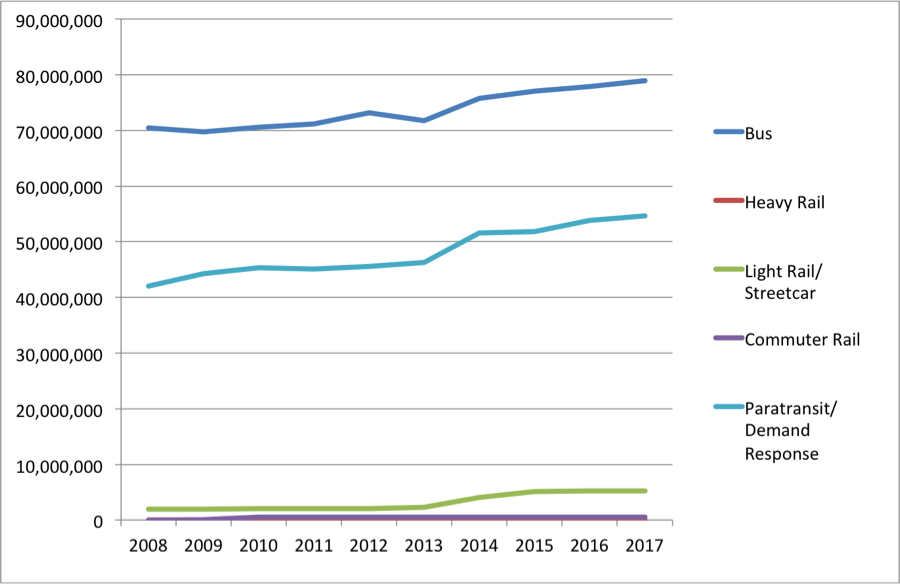

I opened my presentation with a quick overview of ridership statistics from the National Transit Database. After substantial ridership increase from the mid-1990s, the national public transit ridership trend switched course after hitting a peak in 2014. Data shows that total unlinked passenger trips declined 5.4 percent nationwide from 2014 to 2017. The drop was more dramatic for bus service, which lost more than 9 percent of its passenger trips over the same period.

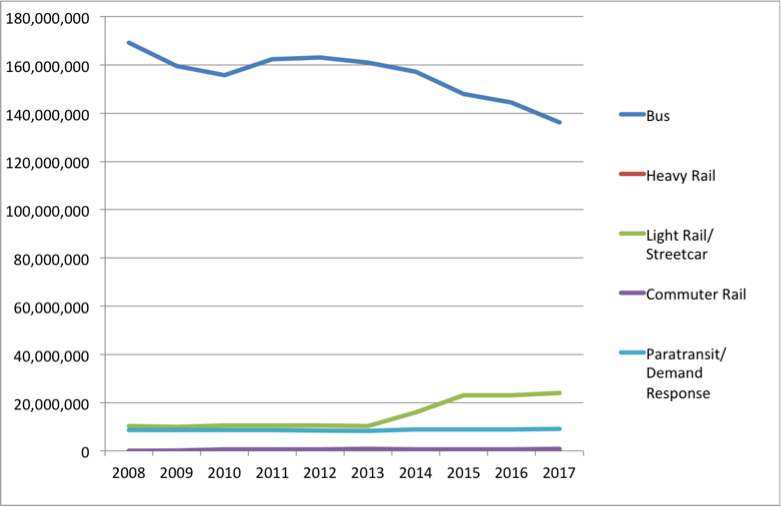

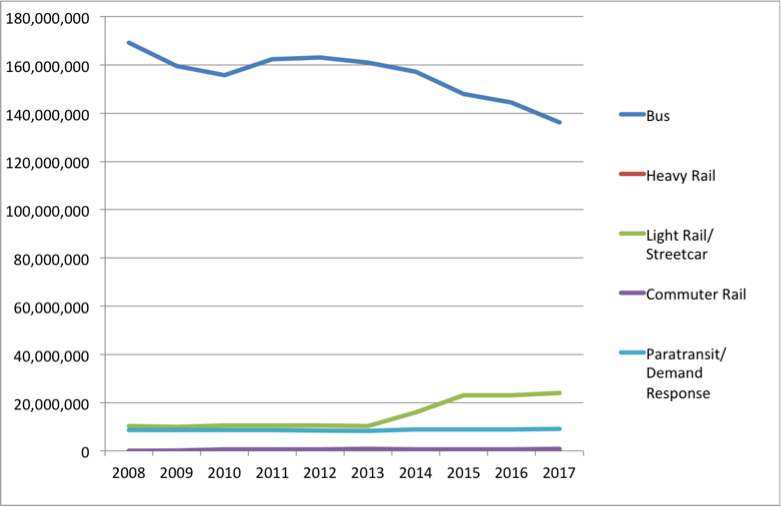

Agencies in Minnesota and Wisconsin face the same trend: a decline of 7 percent for total trips, led by a 13.3 percent dip in bus riders from 2014 to 2017. New investments in light rail in the Twin Cities are boosting transit trips, as shown in Figure 1, but not making up for larger losses.

Figure 1: Unlinked Passenger Trips, Wisconsin and Minnesota

Source: Eno Analysis of National Transit Database

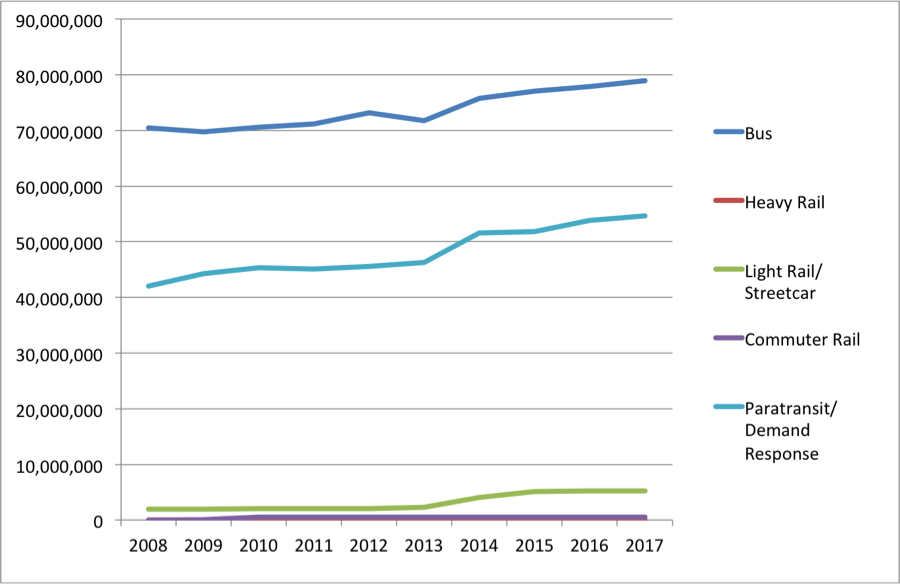

Inversely coupled with the declining ridership, transit vehicle revenue miles have risen. Despite this simultaneous increase in the total number of vehicle miles, agencies are losing riders. Agencies in Wisconsin and Minnesota added 4.1 percent more revenue miles of bus service in the same 2014 to 2017 period where they lost 13.3 percent of their riders, shown in Figure 2. Some regions, including Seattle, Houston, and Rochester, MN have bucked the nationwide trend. Nevertheless, the majority of agencies faces this dilemma and wants to know how to stop, and reverse, the ridership slide.

Figure 2: Vehicle Revenue Miles, Minnesota and Wisconsin

Source: Eno Analysis of National Transit Database

Several studies have attempted to uncover the biggest reasons why transit ridership is declining. A recent report cited competition from new mobility services such as Uber and Lyft as a culprit, particularly in the largest cities. The American Public Transportation Association lists several potential causes, including buses stuck in increasing congestion, reduced customer loyalty, and a decrease in perceived safety. But these factors don’t always apply in the smaller and medium-sized city homes of the bulk of the transit systems in Wisconsin and Minnesota.

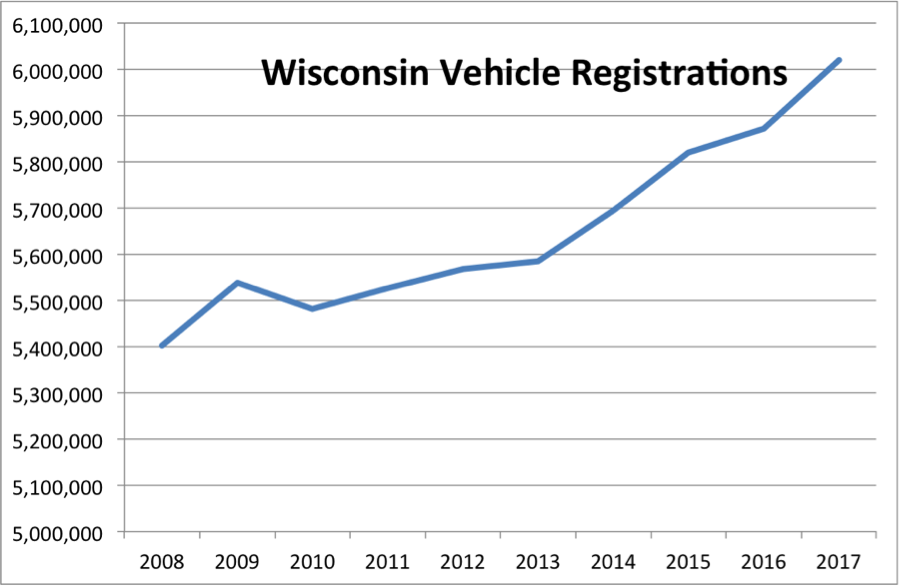

Perhaps a more compelling reason for ridership declines is that people are buying more cars. A recent study from the University of California Los Angeles found that bus ridership declines in Southern California are most strongly correlated with increased auto ownership, with the authors calling cars the “silver bullet.”

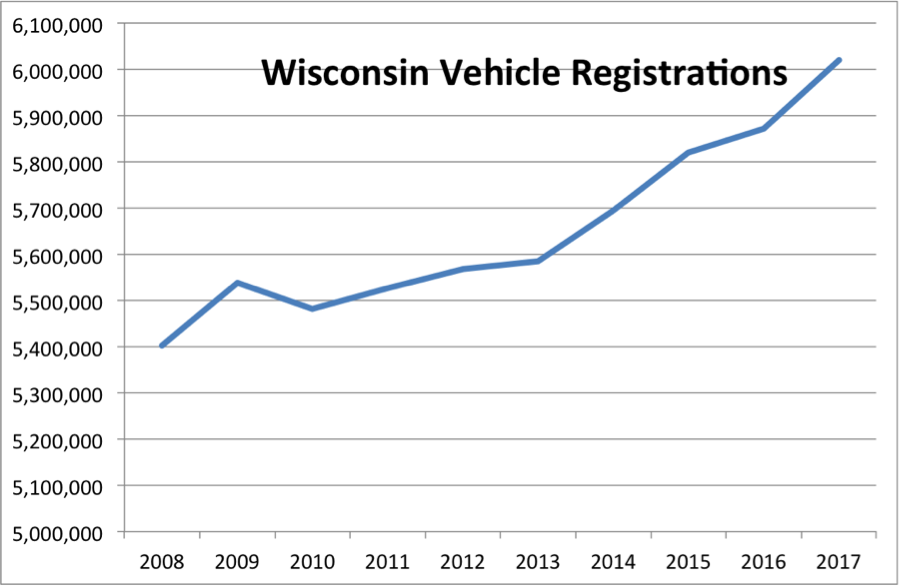

A comparison of bus declines to vehicle registrations in Wisconsin, shown in Figure 3, confirms that suspicion halfway across the country. (Minnesota has similar geography and economy, so vehicle registrations are similar). Between 2009 and 2013, Wisconsin added 46,384 vehicles to state roads. From 2013 to 2017, registrations increased by 433,726. Assuming each of those new cars makes only two trips during workdays, those commutes far exceed the total number of bus trips lost during the same time period. Transit agencies must adapt and respond to the upward trend of car ownership.

Figure 3: Vehicle Registrations in the State of Wisconsin

Source: Wisconsin Department of Motor Vehicles

Conference participants discussed how they might make public transit more competitive with the automobile. SouthWest Transit is offering “SW Prime,” a microtransit option for riders outside of Minneapolis. This service’s flexible bus routes can be requested at any time and take riders directly to their destinations, pooling with other riders traveling in the same direction. However, that service attracts only four riders per hour per vehicle, and the highest-performing microtransit services have a ridership maximum of about five riders per vehicle-hour. While this can be important for low-density areas, it is an expensive way to significantly boost ridership. Conferees also discussed autonomous vehicle shuttles, but none of the technologies available to date can provide reliable service without the use of an on-board attendant, limiting its cost-effectiveness.

To address ridership declines, agencies need to focus on improving current systems beyond adding more vehicle-miles. With federal cash sparse for new streetcar and light rail lines, agencies will need to invest in rethinking the bus network entirely. Proven tactics, such as bus network redesigns, priority lanes, and signal coordination can help make the bus more reliable, convenient, and quicker than a personal car.

Agencies should also expand their partnerships. Tech firms can add value by optimizing routes, streamlining payments, and coordinating an agency’s network with multimodal options. By reaching out to employers to coordinate transit passes and plans, agencies can boost ridership and reduce the need for businesses to supply expensive parking. But partnerships within the public sector also yield innovation. Civic institutions and interagency exchange can enable staff to work jointly on similar problems and share insights. Conferences, like the one in La Crosse, are great way to meet counterparts, and future collaborators, at peer agencies facing the same challenges.

Transit agencies also need to think creatively beyond traditional transit. The newest tech trend of dockless electric scooters might be a way to attract riders to and from the system. Even state and local highway agencies could be welcome collaborators in addressing the growing demand for automobiles on roadway, mitigating congestion, and leveraging transit’s efficiencies to improve access and decrease trip times for the overall network. Bus lanes, parking regulations, and roadway pricing are multimodal solutions that require non-traditional, cross-agency partnerships.

Public transportation will remain an essential part of our economies and transportation system, but it must leverage its strengths and evolve to meet today’s challenges. Agencies at the Minnesota-Wisconsin conference showed an appetite for fresh thinking, and should be encouraged to test and share new approaches with others around the country.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Eno Center for Transportation.