May 5, 2017

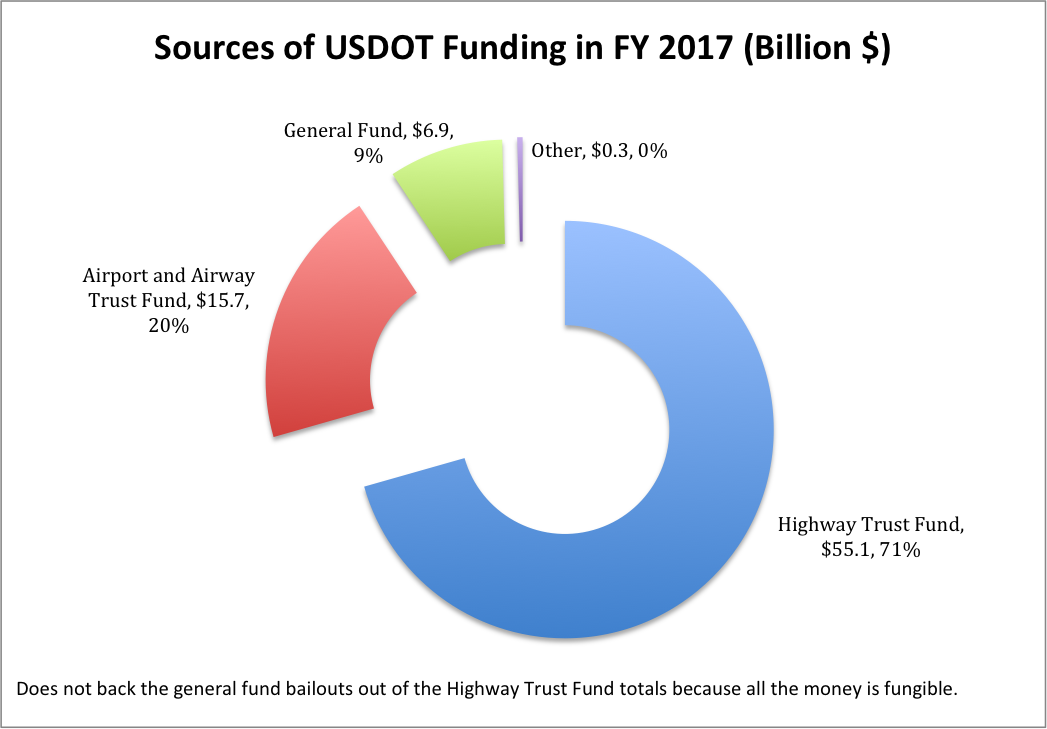

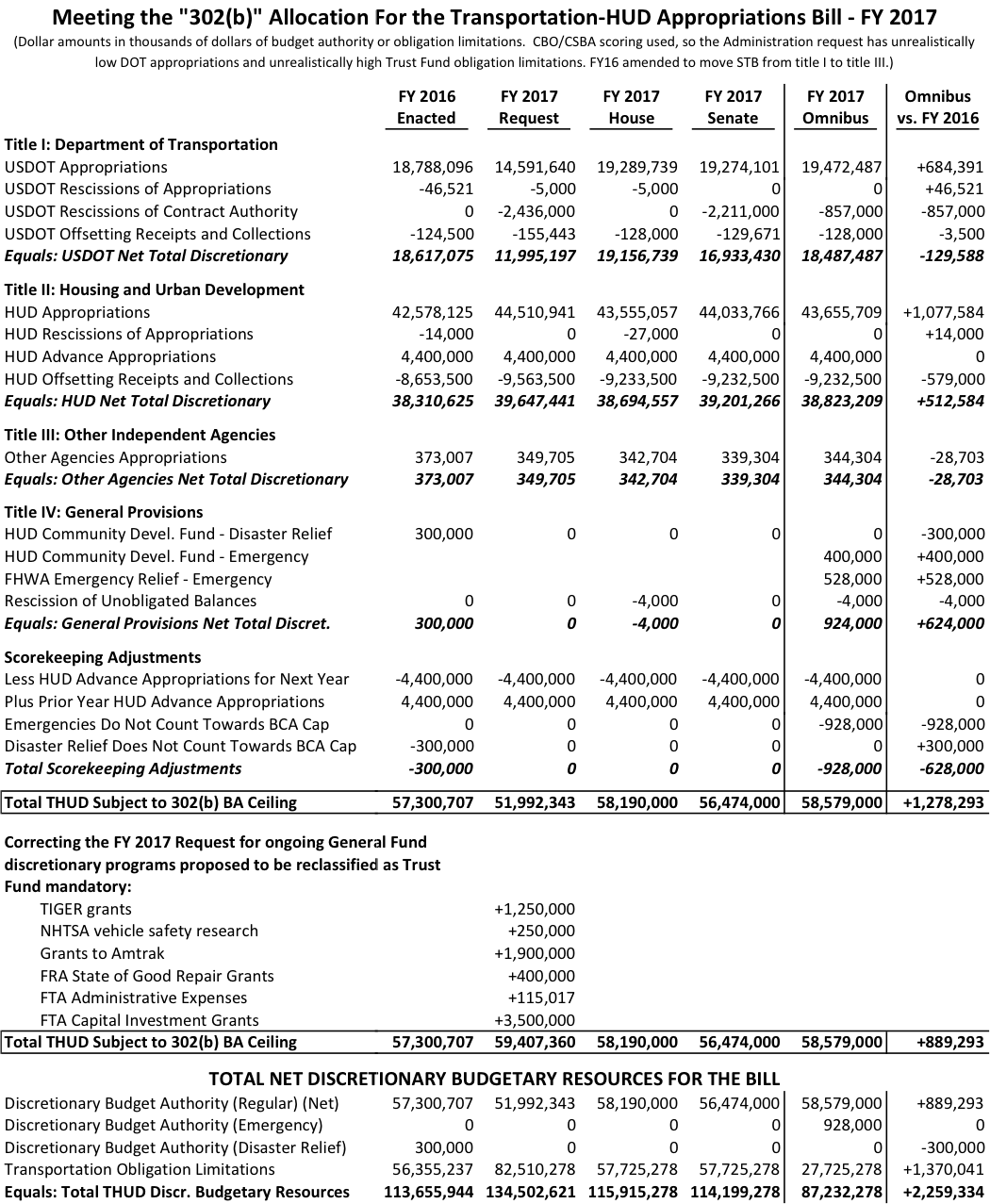

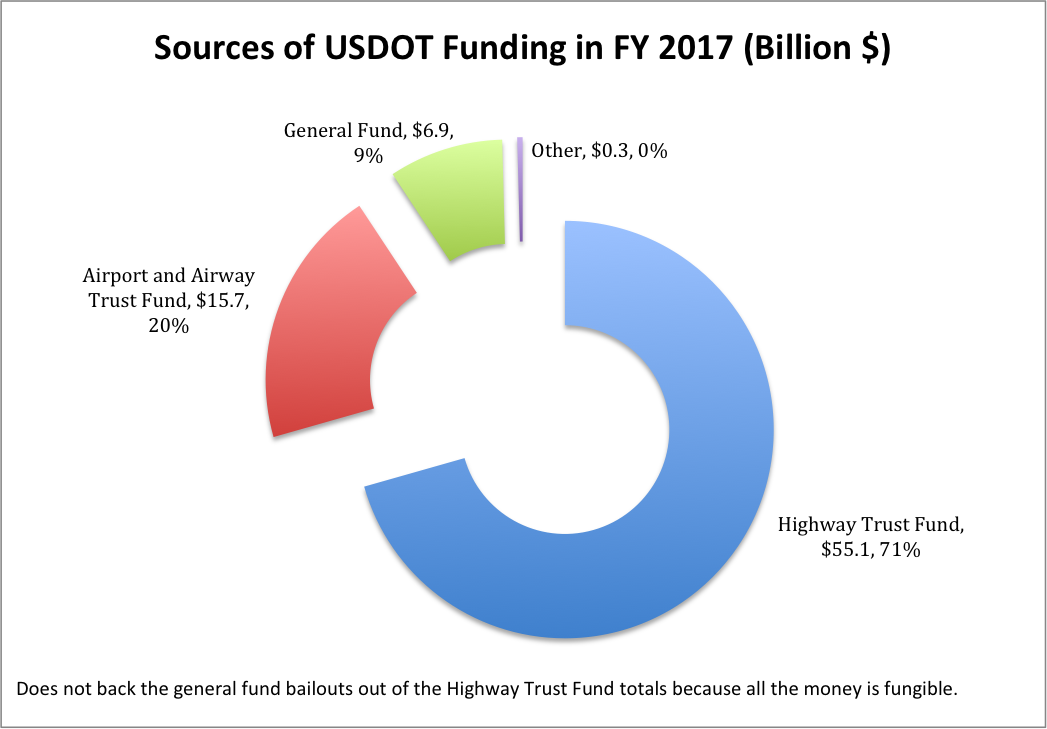

The omnibus appropriations legislation approved by Congress appropriates a gross $19.5 billion for the U.S. Department of Transportation – $650 million more than in fiscal 2016 – and also provides the full $54.4 billion in obligation limitations on Highway Trust Fund contract authority proposed by the FAST Act of 2015. However, the legislation does contain an offsetting rescission of $857 million in highway contract authority balances held by states.

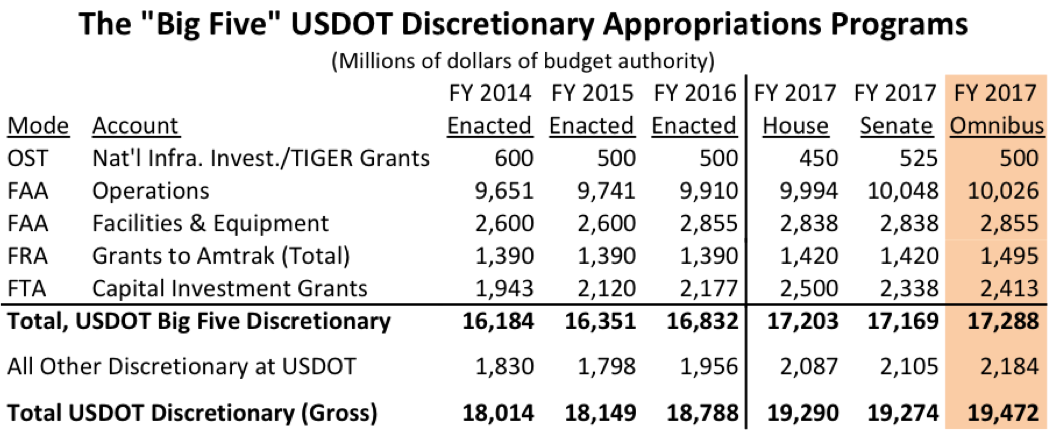

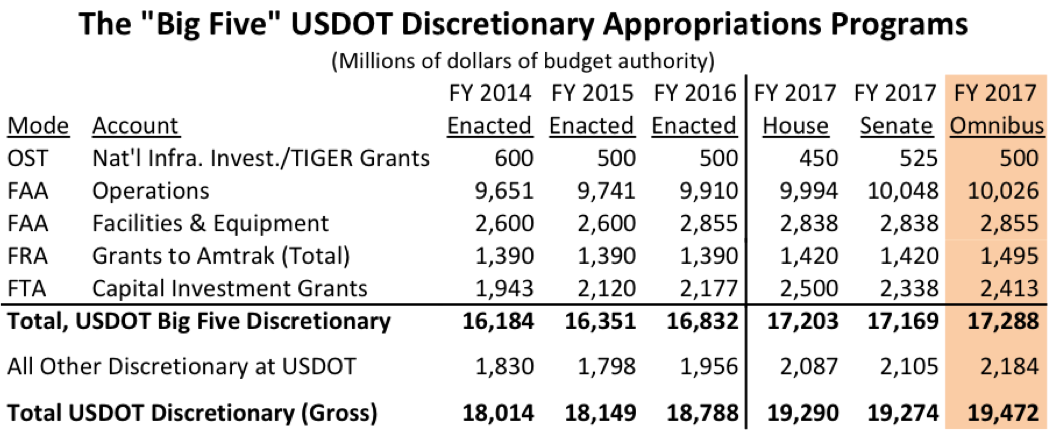

Each year, about 90 percent of the actual appropriations for the Department of Transportation go to just five programs – TIGER grants, FAA Operations, FAA capital (F&E), Amtrak, and FTA capital investment grants. In the omnibus, those five again account for 89 percent of gross USDOT appropriations:

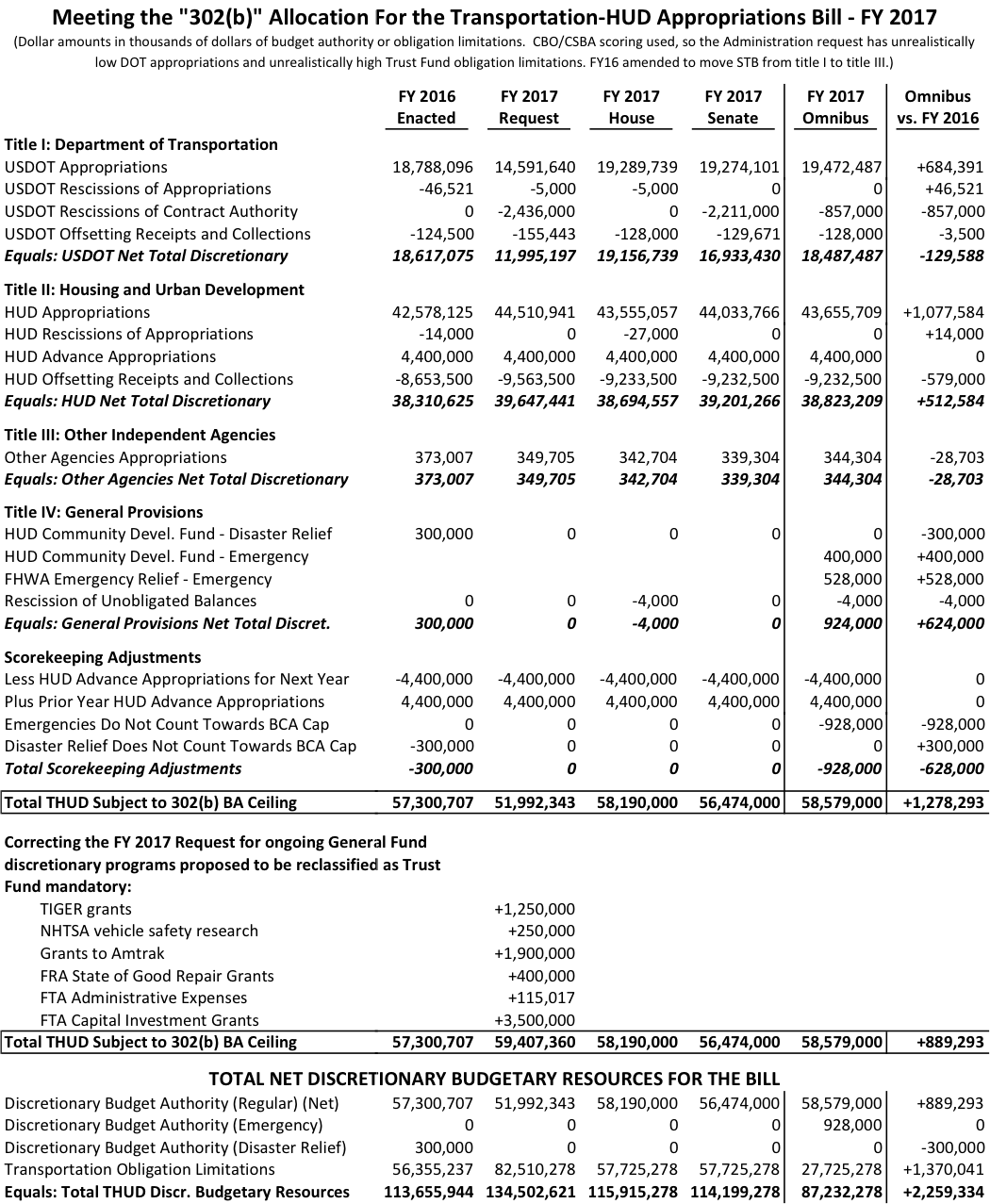

The $19.472 billion gross appropriations total was offset by $128 million in pipeline safety fees and the $857 million highway contract authority rescission for a net total of $18.488 billion. When combined with a net $39.823 billion for the Department of Housing and Urban Development and $344 million for other agencies, the total net appropriations for the Transportation-HUD bill are $58.579 billion

The appropriators ignored the Trump Administration’s last-minute request to zero out funding for the TIGER grant program and to cut funding for FTA Capital Investment Grants down to $1.7 billion. Likewise, the appropriators ignored $1.7 billion in cuts proposed by the White House to HUD programs in FY 2017.

In an unusual step, the final omnibus bill actually appropriates more money on a gross basis for both DOT and HUD than did either of the original House or Senate bills. On a net basis (after factoring in the highway rescission and other offsets), the spending total for the entire bill ($58.579 billion) is $2.105 billion higher than the Senate bill (which had a much larger highway rescission) and $389 million above the House bill (which had no highway rescission at all).

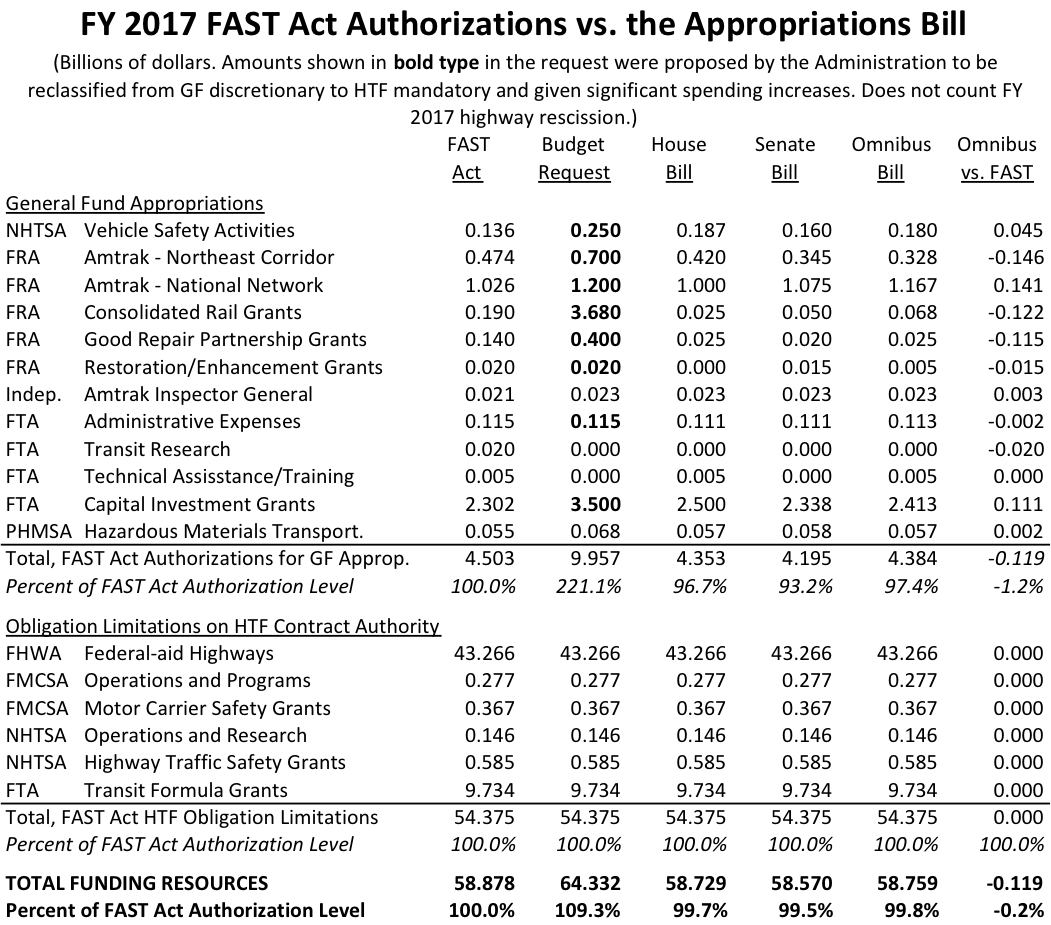

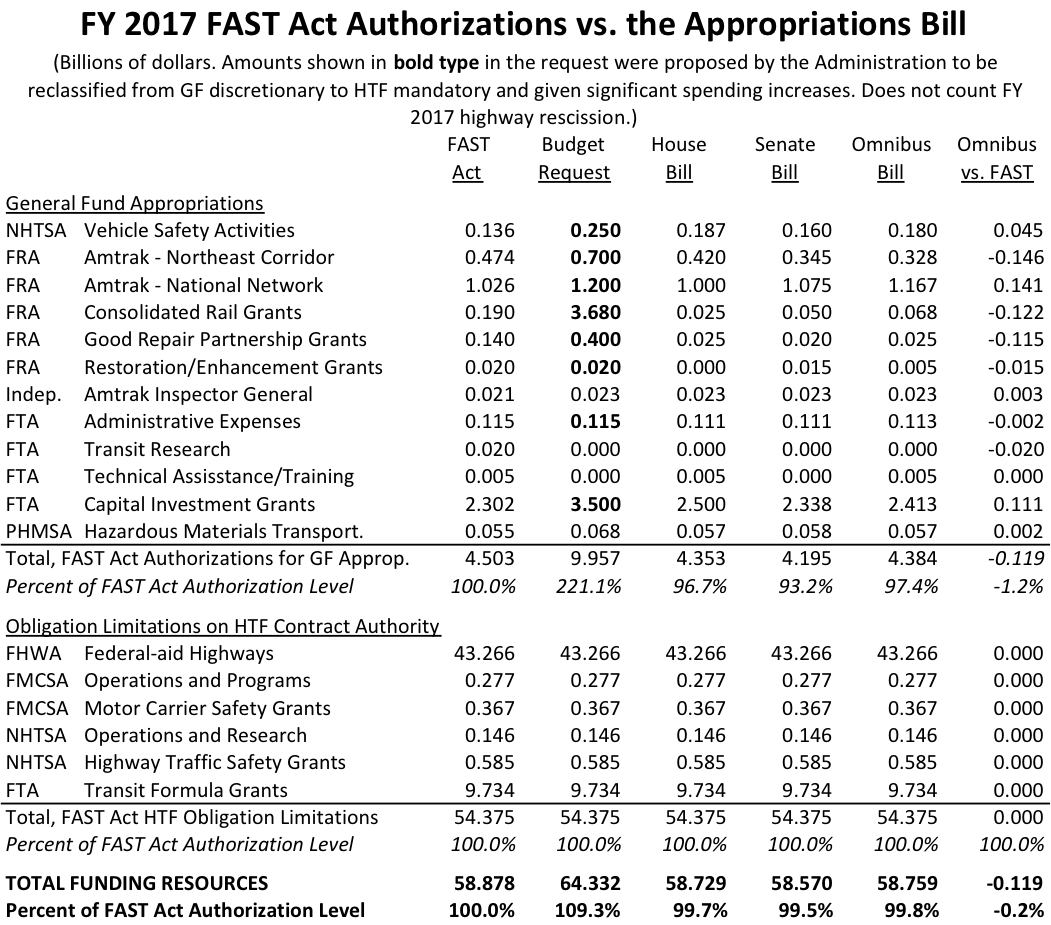

FAST Act. The omnibus bill provides every dollar of Highway Trust Fund obligation authority promised by the FAST Act of 2015 – $54.375 billion in obligation limitations on HTF contract authority. (Such obligation limitations are not subject to the Budget Control Act’s spending caps, so the appropriators have no financial motivation to under-fund those accounts.)

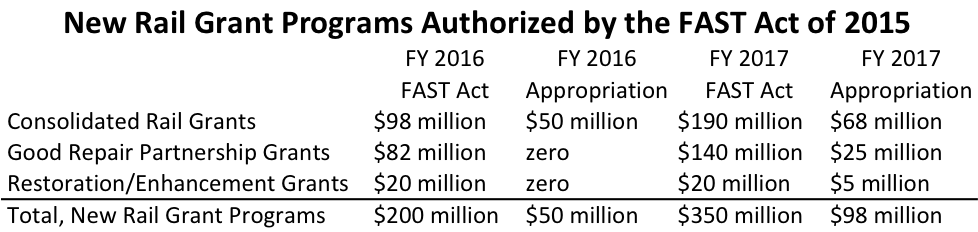

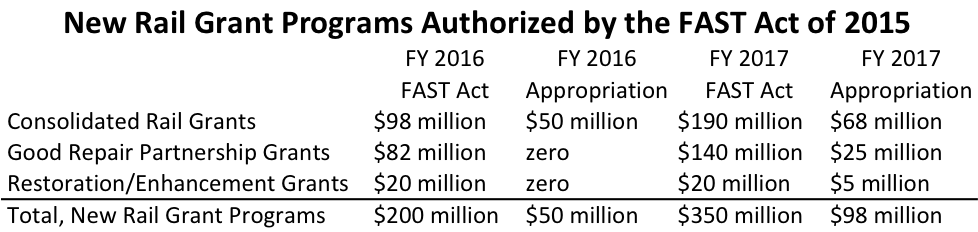

However, the FAST Act also authorized $4.5 billion in discretionary appropriations from the general fund of the Treasury in FY 2017, and those are subject to the Budget Control Act’s $518.5 billion cap on non-defense appropriations. Which makes it remarkable that the appropriators managed to provide an aggregate 97.4 percent of the authorized amount, falling only $119 million short. The major shortages were in new railroad grant programs established by the FAST Act, as it is always more difficult to get a new program funded than it is to maintain or slightly increase funding levels for a program that has been established for years.

Highlights of the transportation funding, by mode, follow.

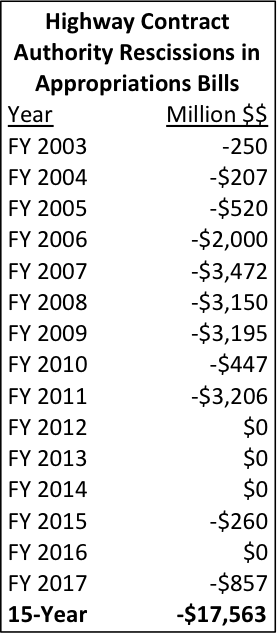

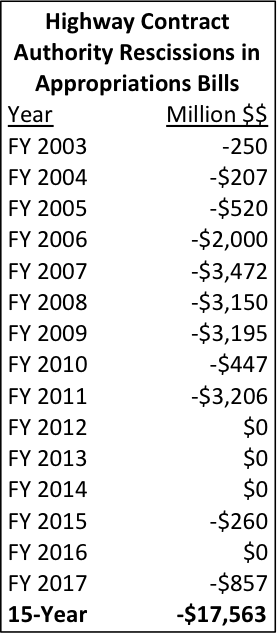

Highways. The legislation provides the full $43,266 billion obligation on the federal-aid highways program recommended by the FAST Act, less the $857 million rescission of contract authority balances held by states (to be applied to states in the ratio of each state’s unobligated balances to the total for all states as of May 31, 2017). President Obama had proposed a rescission of $2.436 billion, which opened the door for the Senate to include a $2.211 billion rescission. (The House bill had no rescission.)

The use of a massive highway rescission to offset new appropriations used to be a popular budget gimmick with the appropriators but died out after 2011. (It is a gimmick because rescinding contract authority outside the obligation limitation does not result in any savings of real dollars (outlays) but can be used to offset new appropriations that will eventually result in real outlays). However, the rescissions can cause programmatic problems for state DOTs. It is impossible to predict with precision which states will be allocated which share of the $857 million because states have from now to May 31 to obligate as much contract authority as they can, which will reduce their share of the rescission. ETW did an analysis of the original Senate rescission last May, which can be read here.

In addition, the bill appropriates an extra $528 million from the general fund for the highway emergency relief program under 23 U.S.C. §125. Section 122 of the legislation allows Virginia and the District of Columbia to collectively transfer $30 million from their highway formula apportionments to the National Park Service to pay for part of the Memorial Bridge repairs. Section 125 of the bill requires the Appropriations Committees to be given the same 60-day notification of FASTLANE grant selections as are the authorizing committees of the House and Senate. Section 422 of the legislation once again lets states reprogram “dead earmarks” that are at least 10 years old and less than 10 percent obligated and transfer that money to surface transportation block grant programs. And section 423 of the legislation designates U.S. 67 in Arkansas as Interstate 57.

Mass transit. The omnibus provides the full $9.734 billion obligation limitation for the federal-aid highway program in fiscal 2017. This includes $199 million in one-time funding for positive train control (PTC) grants to commuter railroads. The bill text allows the federal share of innovation grants under 49 U.S.C. §5312 to exceed 80 percent if the Secretary determines a substantial public interest or benefit.

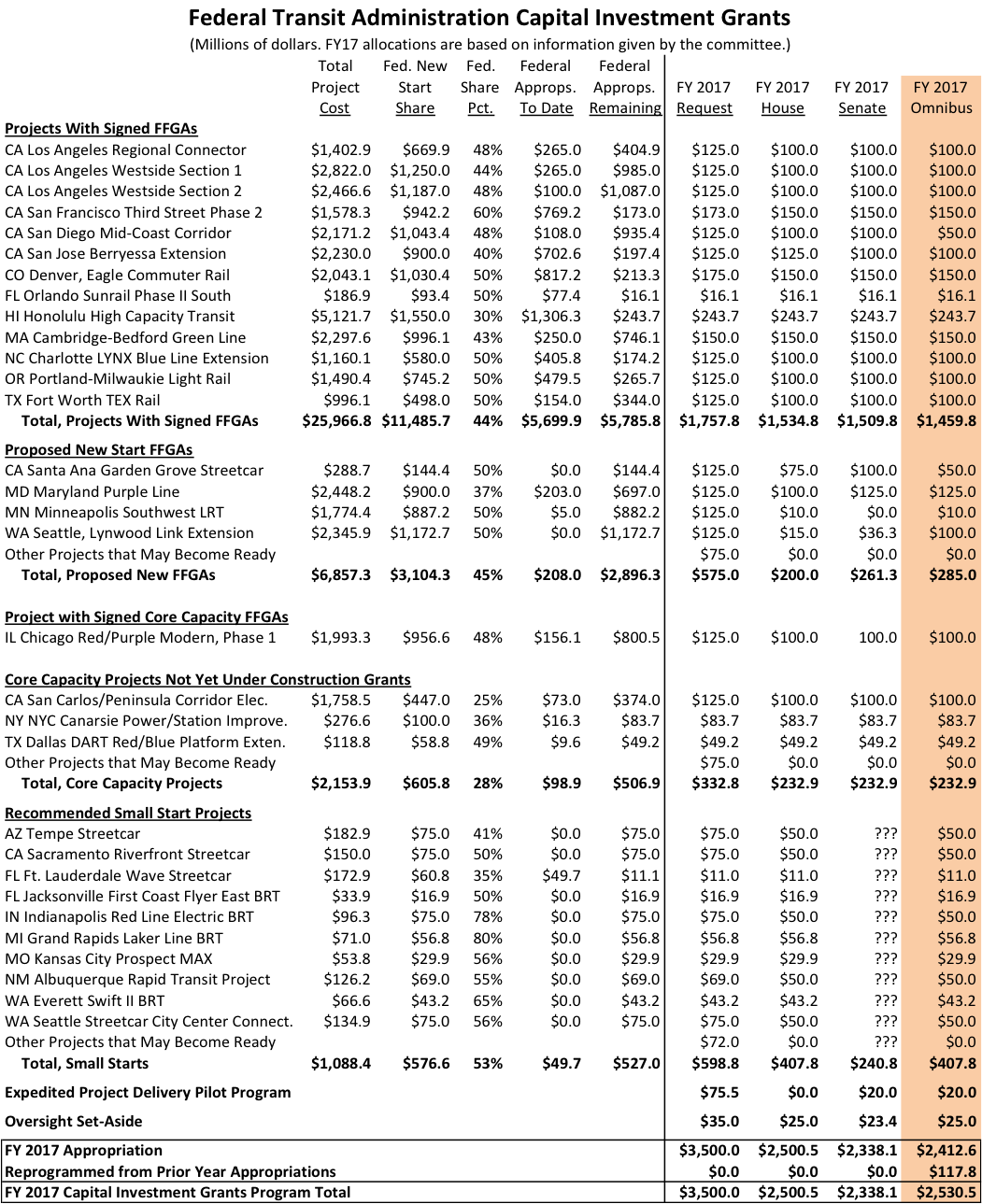

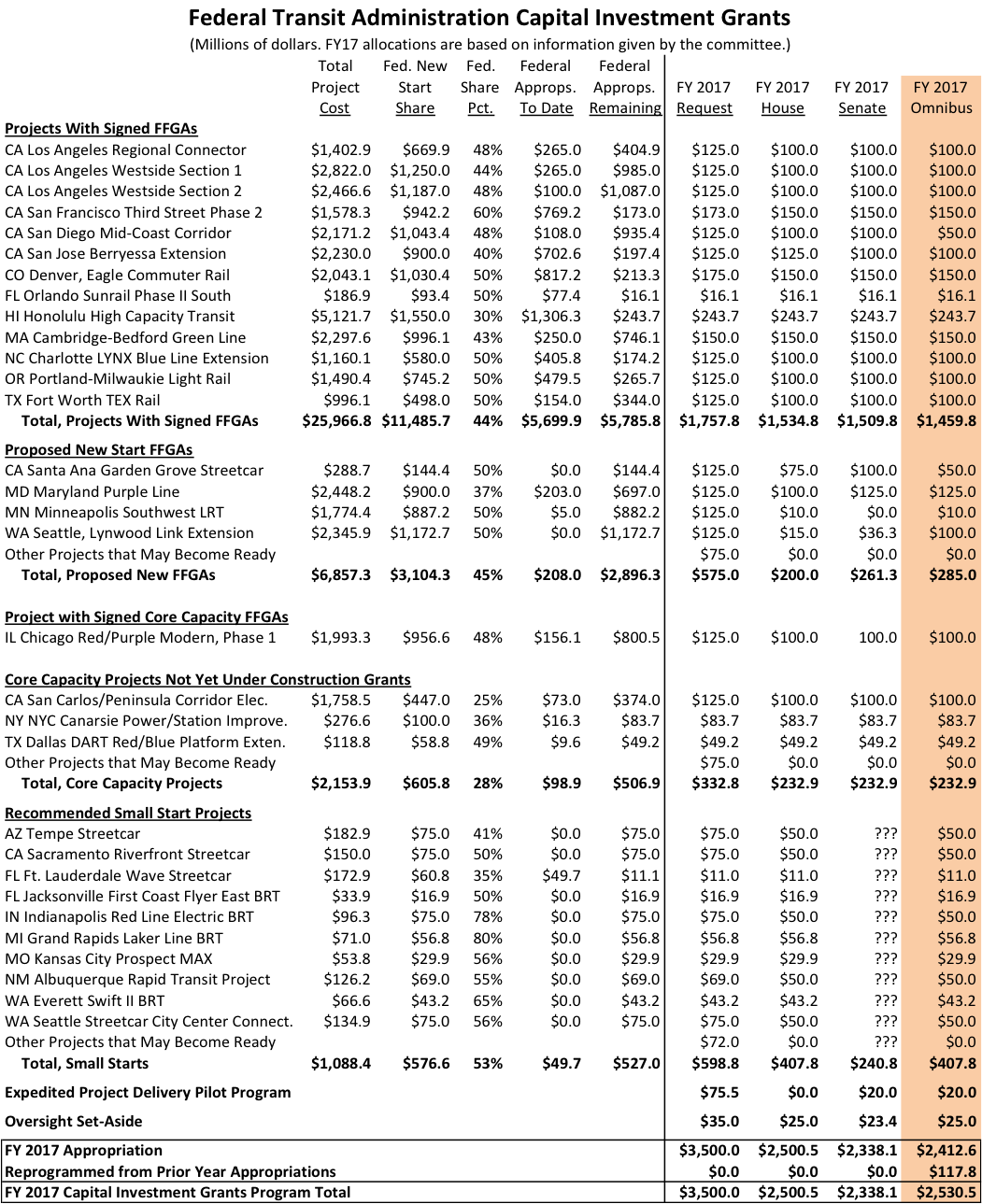

The bill also appropriates $2.413 billion for the capital investment grants program – together with $118 million in balances transferred from old projects that are not needed, the total available for the account is $2.530 billion. In addition to funding the latest installments of projects that have already had their grant agreements executed, the explanatory statement accompanying the bill says that “The Secretary shall administer funding as in the following tables” that include the Maryland Purple Line ($125 million), Caltrain Peninsula Corridor ($100m), Seattle WA Lynnwood Link ($100m), NYC Canarsie Power Improvements ($84m), Santa Ana, CA streetcar ($50m), Dallas DART core capacity ($49m) and Minneapolis Southwest LRT ($10m). The legislation also sets aside $408 million for ten “small start” projects identified in the 2017 budget request.

This sets up an interesting showdown with the Trump Administration, which proposed in its FY 2018 budget outline to stop approving new grant agreements under the CIG program. Legally, the ability of Congress to force the Secretary to approve specific grant agreements via explanatory language in a statement in the Congressional Record is a bit of a gray area. (Once upon a time, the Appropriations Committees wrote the project names and dollar amounts into the text of the law itself to eliminate that gray area.) this will undoubtedly be a major area of questioning for Secretary Chao when she eventually testifies before the Appropriations Committees on the 2018 budget request.

In addition, the bill provides another $150 million installment of funding for the DC Metro subway system (the eighth year of the ten-year, $1.5 billion authorization from the 2008 rail safety law) and also contains a general fund appropriation for $5 million to fund FTA technical assistance and training activities under 49 U.S.C. §5314. The omnibus agreement drops a requirement on page 71 of the Senate committee report that would have required GAO to analyze why transit projects in the U.S. cost so much more than they cost in other G-20 countries.

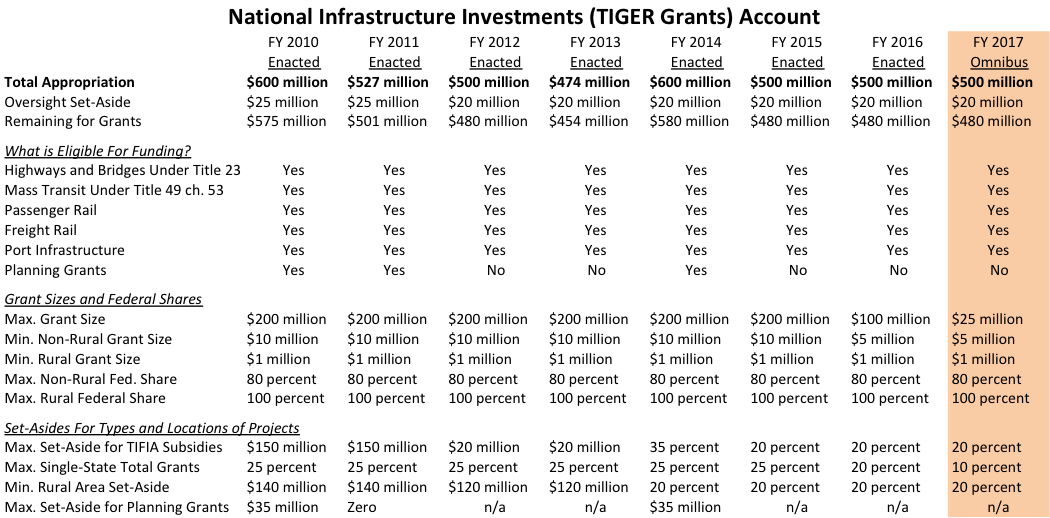

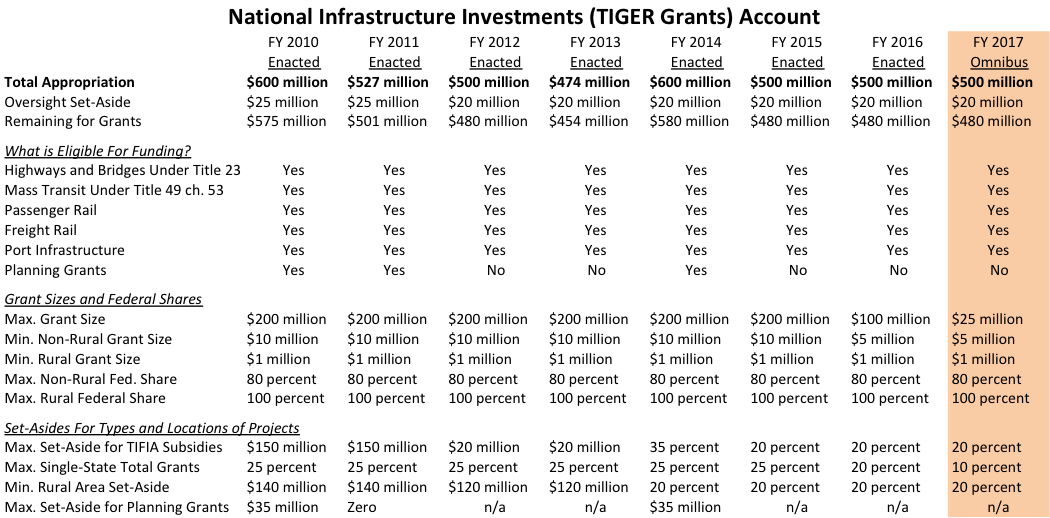

Multimodal. The omnibus legislation appropriates $500 million for the national infrastructure investment (TIGER) grant program in 2017. Most of the terms and conditions appear the same as in prior years except that the maximum grant size is lowered from $100 million to $25 million (this is a legal ratification of an Obama Administration practice – USDOT has not given out a TIGER grant larger than $25 million since fiscal 2011). The maximum share of total annual grants that can go towards projects in any one state drops from 20 percent to 10 percent. And once again, planning grants are not eligible for FY 2017 funding. The bill orders the Secretary to “conduct a new competition to select the grants.” The bill also provides a $3 million appropriation from the general fund for expenses of the National Surface Transportation and Innovative Finance Bureau (which the Obama Administration tried to rename the Build America Bureau).

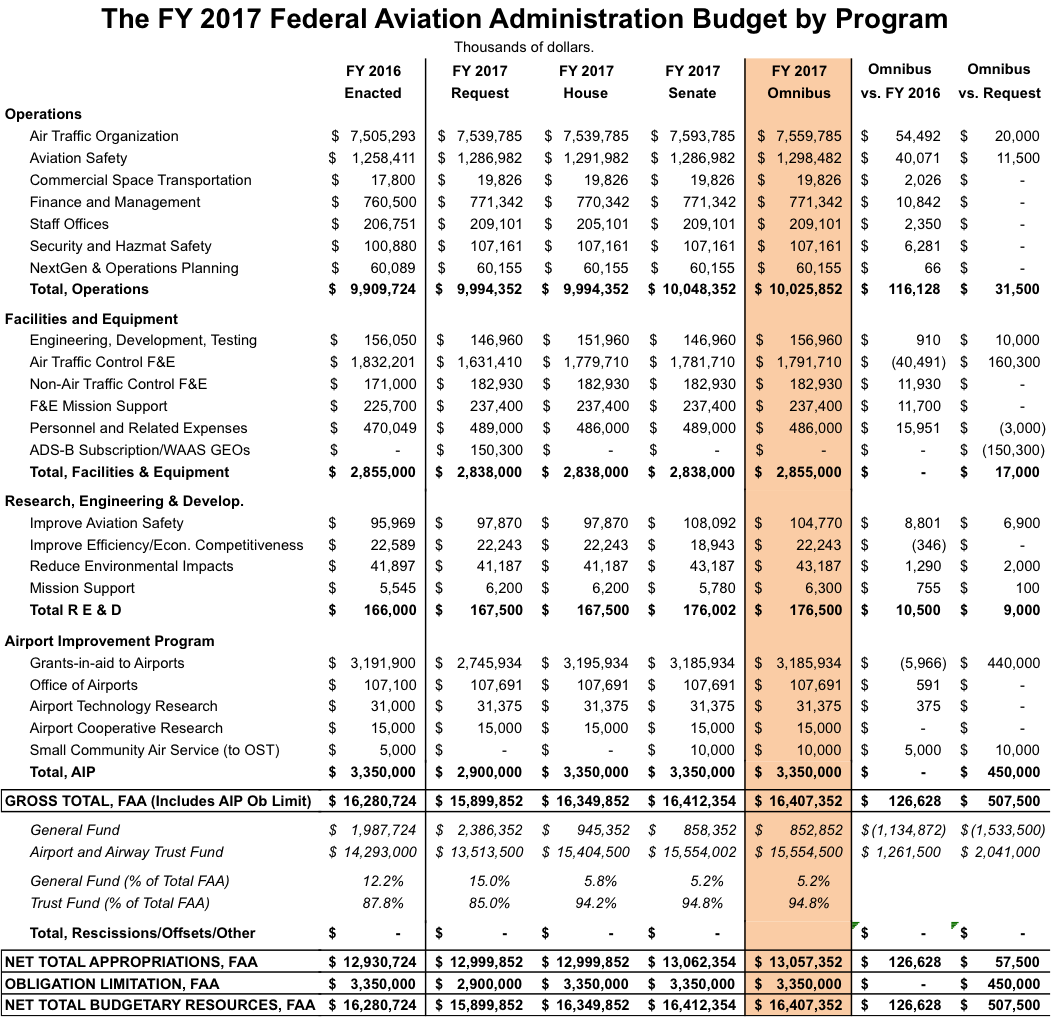

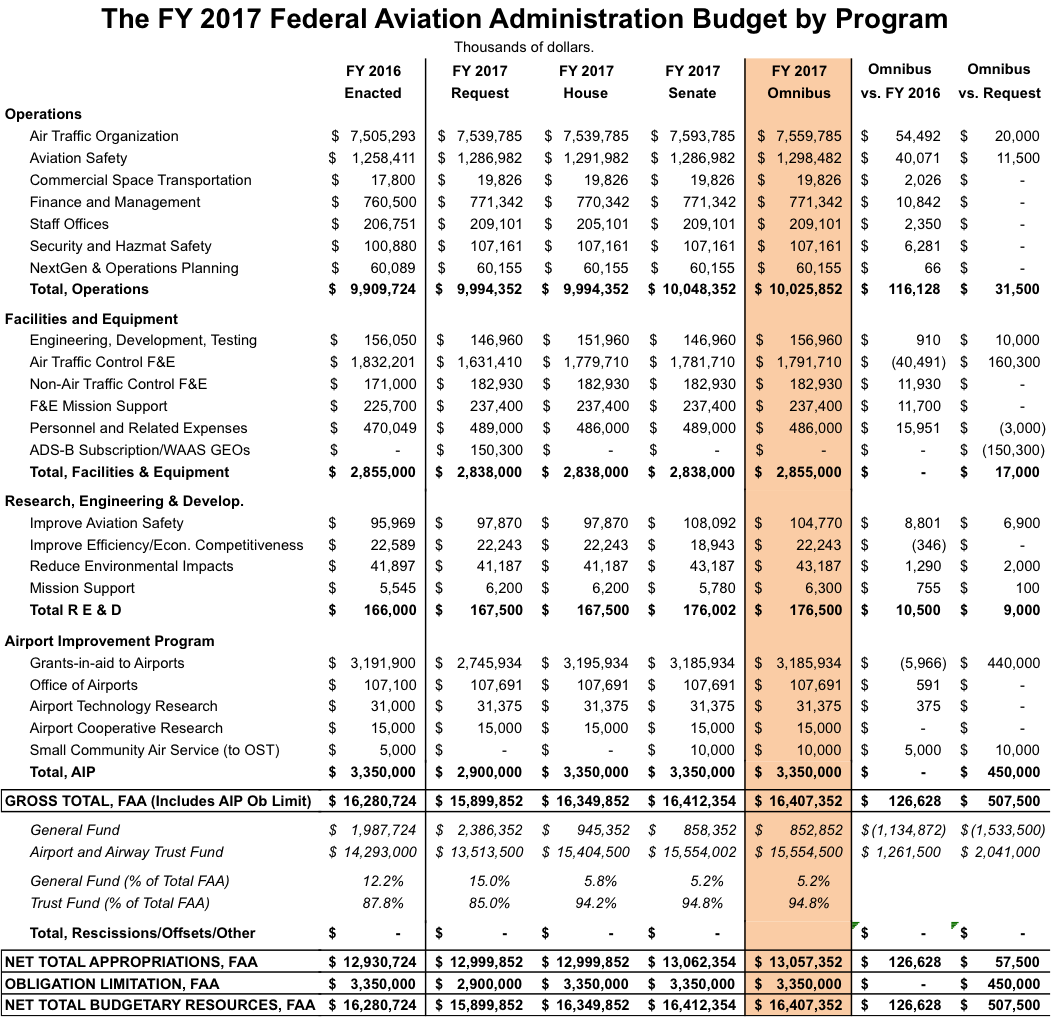

Aviation. The omnibus bill provides $16.4 billion in total budgetary resources for the Federal Aviation Administration for fiscal 2017, a $127 million increase over 2016 and $508 million over the budget request. The big account, Operations, gets a $116 million increase over last year and is $31.5 million over the budget request, $30 million of the increase is for the Air Traffic Organization, to “accelerate the safe integration of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) into the national airspace (NAS)” and the other $1.5 million of which is for six new FTE positions “to support the certification of new technologies and advance FAA’s organizational delegation authorization (ODA) efforts and strengthen safety oversight.” The bill provides $159 million for the contract tower program and prevents the FAA from shutting down the contract weather observers program.

The Facilities and Equipment account is frozen at last year’s $2.855 billion. Within that amount, money is moved around – the System-Wide Information Management (SWIM) program gets $15 million more than the budget request, for example. The conference agreement also orders all FAA facilities to upgrade their data connections to Internet Protocol – apparently, some of facilities still use an old-fashioned TDM data connection, which phone companies are starting to phase out.

The Airport Improvement Program is once again frozen at $3.350 billion, of which $10 million is to be transferred to the Secretary for the Small Community Air Service program. The bill also appropriates an even $150 million to the Secretary to continue carrying out the Essential Air Service subsidy program, the same as the budget request but $25 million less than last year.

By reference, the conference agreement incorporates language from the Senate committee report stating “that air traffic control should remain an inherently governmental function where the Air Traffic Control Organization [ATO] is subject to on-going congressional oversight so that resource needs and activities are reviewed. The annual congressional oversight process is best suited to protect consumers and preserve access to urban, suburban and rural communities.”

Rail. The bill gives Amtrak a $75 million budget increase above last year, from $1.420 billion to $1.495 billion. The money is split via the new account structure established in the FAST Act – $328 million for the Northeast Corridor and $1.167 billion for the rest of the network, including the money-losing long-distance trains. Of the NEC money, $50 million is for ADA compliance and $5 million is for the Northeast Corridor Commission. Of the National Network money, $2 million is set aside for the State-Supported Route Committee. The final bill does appropriate money for the new Federal Railroad Administration grant programs established by the FAST Act – $68 million for the consolidated grant program, $25 million for the federal-state SOGR partnership program, and $5 million for the rail restoration and enhancement grant program.

Safety. The bill meets the FAST Act levels for Highway Trust Fund support for the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. For NHTSA, the bill also provides a substantial increase in general fund appropriations for vehicle safety activities – a total of $180 million, well above last year’s $153 million and above the $136 million authorized by the FAST Act. Most of that increase is allocated as follows: “within Enforcement programs, the agreement provides a $17,000,000 increase for the Office of Defects Investigation and $1,500,000 to fund grants to States that use vehicle registrations to notify vehicle owners and lessees of open recalls as authorized under Section 24105 of the FAST Act. Within Research and Analysis programs, the agreement provides a $6,500,000 increase for Vehicle Electronics and Emerging Technologies.”

At FMCSA, section 419 of the omnibus bill formally amends section 395 of title 49 of the Code of Federal Regulations to reflect the permanent suspension of portions of the FMCSA hours of service rule that was nullified by language in prior year appropriations laws. The explanatory statement also directs NHTSA and FMCSA to “fully and adequately address all comments received from the public” on the proposed rule requiring speed limiters on heavy trucks and buses and says the final rule “should address the impact of creating speed differentials on highways and consider the costs and benefits of applying the rule to existing heavy vehicles that are equipped with speed limiting devices.”

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration gets a gross total of $156 million for pipeline safety, mostly offset by $128 million in pipeline safety user fees and a new $8 million underground gas safety facility fee imposed by the recent PIPES Act. Hazmat safety and PHMSA operational expenses got increases over the 2016 level, but those increases were not nearly as large as the increases requested by the Obama Administration.

The independent National Transportation Safety Board receives an appropriation of $106 million.

Maritime. The Maritime Administration got a huge spending increase over last year – $523 million versus $399 million. However, most of that increase was the one spending account at USDOT that is not subject to the non-defense discretionary spending cap (MARAD’s security program is subject to the defense budget cap, and it went from $210 million last year to $300 million this year). But the ship disposal account also got a huge increase, from last year’s $5 million to $34 million in 2017.

The final bill does not appropriate any money to make new title XI shipbuilding loans, but neither does it reach back and rescind the $5 million for such loans appropriated last year, as the President proposed and the House bill would have done.

The St. Lawrence Seaway Development Corporation receives an appropriation of $36 million for operating expenses.

A detailed, account-by-account table of the USDOT budget can be downloaded in PDF format here.