Mode Choice for Urban Mobility

Light Rail and Streetcars in the news

In May 2025, Washington D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser announced the replacement of the DC Streetcar with “next generation streetcars,” and the end of streetcar funding in two years. These “next generation streetcars” will be electric buses powered by the overhead lines currently being used by the fixed rail streetcar. The DC streetcar was envisioned as a system of multiple lines but following years of delays and changes to the project, only one line operates between Union Station and Benning Road.

D.C.’s pivot is not an outlier. Across the country, cities are reassessing or have announced cancellations or delays in light rail and streetcar projects. In September 2025, city officials in St. Louis, MO announced plans to cancel the proposed north-south MetroLink Green line. The new light rail project was slated to cost $1.1 billion, adding ten new stations over six miles. According to city officials, the high cost of the project made it uncompetitive for federal funding. The city is now considering bus rapid transit as an alternative. In June 2025, the Ramsey County Board in Minnesota pulled its support for a new streetcar line in downtown St. Paul and voiced its commitment to use the $730 million that was originally set aside for the new streetcar for other transportation projects.

The headwinds are not only financial but political. The mayor of Atlanta, Georgia pulled his support for a proposed Beltline light rail project and in Phoenix, Arizona, a 2023 law prohibited the use of public dollars from being used to expand light rail near the state capitol complex, necessitating a change in the city’s light rail expansion plan. In both cities, the future of light rail expansion remains uncertain.

This is not the first time that light rail and streetcar projects have struggled. In the early 20th century, streetcar systems dominated cities large and small across the United States, followed by a steady decline with the rise of the automobile. Modern street-running light rail systems re-emerged in the 1980s with new systems in San Diego and Portland, ushering a renaissance of light rail and streetcar development in the 1990s and 2000s. But the recent light rail and streetcar announcements in 2025 begs the question: is the renaissance in light rail and streetcar development over?

Light Rail, Streetcar, and BRT ridership

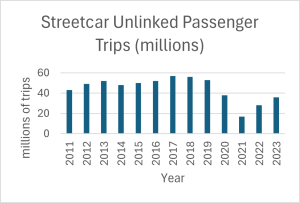

Light rail, streetcars, and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) are all forms of fixed-guideway transit that provide mobility in urban areas. After the expansion of new systems and ridership, the period between 2011 and 2020 saw relatively constant ridership for light rail. Ridership for BRT and streetcar increased from 2011 to 2020, with BRT seeing a significant increase. For all three modes, ridership took a hit during the Covid-19 pandemic, but while BRT ridership has since returned to pre-pandemic levels, neither light rail nor streetcar ridership has fully recovered.

Figure 3. Unlinked Passenger Trips for BRT vs. Light Rail 2011-2023

Source: APTA, 2025 Public Transportation Factbook Appendix A, 2025.

Funding for Light Rail, Streetcars, and BRT

Capital funds for light rail, streetcars and BRT projects come from a variety of federal sources, including the Capital Investment Grant (CIG) program and BUILD (formerly RAISE/ TIGER). Administered by the FTA, projects under the CIG program are categorized as New Starts or Small Starts. Light rail projects typically fall under the New Starts category which provides grants for large, fixed guideway projects that cost $400 million or more. BRT and streetcar projects typically fall under the Small Starts category, which provide grants for fixed-guideway projects that cost less than $400 million. Light rail, streetcar, and BRT projects are also eligible for BUILD grants.

In FY 2007, 28 projects were supported by CIG, of which 15 were investments in light rail, and one was a BRT project, and there were zero streetcar projects. In comparison in FY2017, among the 31 listed CIG projects, ten were light rail projects, six were BRT, and five were streetcar projects. In other words, between FY07 and FY17, federal support for light rail did not disappear, but it did shift to more support for BRT and streetcars. This trend has only accelerated since 2017. In 2024, among the 50 current CIG projects that are receiving construction grants or seeking construction grants, 30 are BRT projects, illustrating the dominance of BRT investment across the country. There are only four projects focused on light rail and two streetcar projects.

For streetcars, the BUILD discretionary grants were a major source of federal investment, with heavy investment in streetcar projects between 2009 and 2015. There was relatively little federal funding for light rail and BRT projects during that time. The trend in federal shifted towards BRT in 2014, with a significant increase in investment from 2014 to 2024.

Figure 1. Number of Light rail, Streetcar, and BRT projects awarded under BUILD

| Year | Light Rail projects | Light Rail Grant Awards | Streetcar projects | Total Streetcar Grant Awards | BRT projects | Total BRT Grant Awards |

| 2009 | 1 | $25,000,000 | 4 | $154,203,988 | 2 | $44,000,000 |

| 2010 | 0 | $0 | 2 | $73,667,777 | 1 | $10,000,000 |

| 2011 | 4 | $43,000,000 | 1 | $10,920,000 | 0 | $0 |

| 2012 | 1 | $10,000,000 | 1 | $18,000,000 | 0 | $0 |

| 2013 | 0 | 0 | 1 | $20,000,000 | 0 | $0 |

| 2014 | 2 | $11,900,000 | 2 | $25,200,000 | 3 | $55,860,000 |

| 2015 | 0 | $0 | 2 | $29,200,000 | 3 | $46,910,000 |

| 2016 | 0 | $0 | 0 | $0 | 1 | $10,000,000 |

| 2017 | 0 | $0 | 0 | $0 | 1 | $12,629,760 |

| 2018 | 0 | $0 | 0 | $0 | 3 | $43,875,250 |

| 2019 | 0 | $0 | 0 | $0 | 2 | $27,000,000 |

| 2020 | 0 | 0 | 1 | $14,199,453 | 0 | $0 |

| 2021 | 0 | $0 | 0 | $0 | 1 | $19,000,000 |

| 2022 | 0 | $0 | 0 | $0 | 2 | $27,164,000 |

| 2023 | 0 | $0 | 0 | $0 | 5 | $95,861,631 |

| 2024 | 1 | $15,000,000 | 1 | $15,939,835 | 1 | $12,728,889 |

Source: USDOT, Awarded Projects for TIGER/RAISE/BUILD from 2009 to 2025, https://www.transportation.gov/BUILDgrants/all-awards.

Choosing BRT over Light Rail and Streetcars

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, light‑rail and streetcar ridership has rebounded nationwide from a steep decline but remains below pre‑pandemic levels. In comparison, BRT ridership reached pre-pandemic levels in 2023. The combination of ridership trends, federal investment, and recent cancellations/delays in light rail and streetcar project make clear that cities are generally investing in BRT projects more than light rail projects, with cities like Miami, Raleigh, Madison, Minneapolis, and Austin all investing in BRT.

An important factor in understanding the shift to BRT is cost; light rail is considerably more expensive to build than Streetcars, and BRT is even less expensive still. Light rail costs include adding new rail lines, new facilities, and purchase of high-capacity vehicles. BRT and streetcar vehicles are lower capacity and lower cost compared to light rail. BRT has even lower costs because it has fewer in-street infrastructure needs. In Toronto, the proposed Mississauga-Dundas BRT is projected to cost CAD 580 million ($415 million) for a 4-mile BRT line (around $103 million per mile). As a comparison, the MD Purple Line light rail project is set to cost $9 billion for a 16-mile line (around $562 million per mile).

The capital cost of putting in new light rail lines or light rail line extensions is an important factor pushing some cities from light rail to BRT, such as in the case of the cancelled St. Louis MetroLink Green line. In 2023, the Atlanta transit system, MARTA, canceled plans to construct a $2.9 billion light rail line in favor of a $1.4 billion BRT line, saving the agency $1.5 billion.

In addition to lower costs, BRT systems offer less intensive construction and more flexible operations. Cities can convert general-purpose lanes into dedicated BRT corridors and begin service quickly without the need for entirely new guideways, as required for light rail or streetcar systems. Operationally, BRT can run in dedicated lanes and then leave them to serve streets off‑corridor, allowing service wherever roads exist.

Legislative changes have contributed to shifts in investment choices. Congress added the Small Starts category to the Capital Improvement Grants as part of SAFETEA-LU, which encouraged investments in less expensive projects, including BRT and streetcars. In 2015, the FAST Act eliminated the CIG requirement for corridor-based BRT projects to provide frequent service on weekends. As a result, BRT projects that operate service in mixed traffic would be eligible for CIG even if they only provide frequent weekday service, allowing for more BRT projects to be eligible for federal funding.

However, not all investment is shifting away from rail, particularly in locations with existing systems. In Los Angeles, the city is expanding its light rail system, adding 9 miles and 4 stations to Metro A line. In Maryland, the new purple line will intersect with the DC metro system and MARC commuter rail system. Kansas City is expanding its streetcar system with a 3.4-mile Main Street extension, doubling the length of the existing system. There are also ongoing streetcar expansion projects in Sacramento and Portland.

Looking ahead, light rail and streetcar development is a mixed bag. Cost, political pressures, and mobility needs are determining factors in which mode localities choose to invest. In cases where cities are interested in transit-oriented development, all three modes are valuable in their ability to provide mobility that connects people to housing, employment, entertainment, education, and healthcare within a city. However, the lower cost of construction and greater flexibility of BRT have made it a more attractive option for cities, beating out both light rail and streetcars.