Major Changes Proposed for Regulations and Reviews as Part of Budget Reconciliation

The House continued its work on the budget reconciliation this week with a markup in the House Natural Resources Committee. With this title done, eight of the eleven House committees that received reconciliation instruction have now completed their work. The three outstanding committees that received reconciliation instructions but have not marked up bills are the Agriculture, Energy and Commerce, and Ways and Means Committees. Each of those three committees have informally indicated that they will hold markups on Tuesday May 13th, but none have yet released bill text nor posted official notices of their markups on the committees’ websites.

While the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee’s title, covered by Eno’s Jeff Davis here, has the most direct and significant implications for transportation projects, the House Natural Resources title and the Judiciary title both included provisions with major regulatory implications for transportation stakeholders.

House Natural Resources Title

As would be expected, the House Natural Resources Committee (HNR) bill includes provisions to increase leases and reduce royalty rates for oil, gas, and coal, including mandates for quarterly leases and expansion of leases in the Western Gulf of Mexico, Alaska’s Cook Inlet, and in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. HNR’s markup was a marathon twelve-hour business meeting in which only one amendment other than the substitute was accepted. (That amendment, from Reps. Mark Amodei (R-NV) and Celeste Maloy (R-UT) would require the Bureau of Land Management to sell thousands of acres of public lands in Nevada and Utah, for affordable housing and other undisclosed purposes.)

Of perhaps more significance for transportation stakeholders, the HNR bill also included a significant change for environmental reviews, amending the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to create a new section of “Project Sponsor Opt-In Fees for Environmental Review”. This new section of NEPA would allow project proponents to pay a fee in exchange for a shortened deadline for the environmental review and the complete waiver of all judicial and administrative review of the environmental analysis.

Specifically, a project proponent would pay 125 percent of the agency’s anticipated costs, and the agency would face an immutable deadline of six months in the case of an Environmental Assessment (EA), or one year in the case of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). (Deadlines previously created by the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) amendments to NEPA limit EAs to one year and EISes to two years, although agencies also may extend this deadline as needed, in consultation with the project proponent.)

With regard to the review waivers, the provision is clear that “there shall be no administrative or judicial review of an environmental assessment or environmental impact statement” paid for under the section. This applies even in the case of a document prepared by the project proponent themselves rather than by the agency, in which case the fee paid is limited to the agency’s cost in “supervising preparation of” the document. On the other hand, the committee print does imply that there could still be some administrative and judicial reviewability of the final agency action on those documents, e.g. the Finding of No Significant Impact, in the case of an EA, and the Record of Decision, in the case of an EIS. However, the section still significantly limits that review by noting that the action “may not challenge the finding of no significant impact or record of decision based on an alleged issue with the environmental assessment or environmental impact statement” that has been paid for by a proponent under this section. It’s not entirely clear what could be challenged, if the underlying analysis of the EA and EIS is not reviewable.

How NEPA fees could work in practice

Setting aside questions of whether this provision would survive the Senate’s Byrd challenge for now, if enacted, this provision would have significant implications for environmental reviews. Under current law and under many agencies’ regulations, it is already allowable that proponents of a federal action may prepare an EIS or may fund the preparation of an EIS by a contractor or consultant. Use of a funded third-party contractor is more common and of long-standing practice than the applicant preparation, which was only added in the FRA amendments to NEPA in 2023. For instance, the Fish and Wildlife Service conservation planning handbook notes that with regard to Habitat Conservation Plans (HCP), “EAs or EISs associated with an HCP almost always are prepared by a contractor paid by the applicant, because the Services typically do not have adequate resources to meet the applicant’s timing needs.” Under current law, “the lead agency shall independently evaluate the environmental document and shall take responsibility for the contents.” This provision in the HNR title appears to remove that requirement.

Ultimately though, the Finding of No Significance and the Record of Decision are agency documents detailing the agency’s confidence that the action complies with agency standards and other federal regulations, and are signed by senior agency officials. The preparation of the documents by project proponents, with only limited agency supervision and without any administrative review, may make it difficult for those agency officials to sign those documents and attest that their agency has complied with NEPA requirements.

Another potential implementation challenge will be the fact that NEPA documents are integrated with numerous other environmental laws and regulations. While NEPA is the most litigated federal environmental law, it is far from the only way that litigation is brought. This provision waives the judicial review of the EA and EIS documents, but does not waive review of documents produced pursuant to the Endangered Species Act, another major source of litigation, nor the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Marine Mammals Protection Act, or any of the dozens of other laws, regulations, and treaties which may require a permit or approval on any given federal action.

In an effort to better integrate federal reviews and actions, current practice is for agencies to include all relevant analysis in NEPA documents so as to produce “One Federal Decision.” However the requirement to produce that analysis to satisfy other environmental laws—and the litigation risk associated with those laws—still exists outside of NEPA. Constraining the NEPA document and limiting review of that document could perversely result in a proliferation of smaller, uncoordinated environmental reviews and documents for a single project.

NEPA Fee amount and Revenue

The Committee press release suggests that their NEPA provisions are estimated to generate more than $1 billion in savings and new revenue for the Federal government, based on an estimate that “environmental analysis add[s] an estimated average of $4.2 million to project costs.” That data, which the Committee cites from an American Petroleum Institute one-pager, is actually from a 2016 newsletter from the US Department of Energy, which looked at the costs of three EISes completed by DOE in 2015 and found a $4.2 million average cost, and a $1.47 million median cost. As another DOE newsletter in the same series indicated in 2013, “data on average EIS costs should be interpreted cautiously in view of the relatively small number of EISs and the influence that a single extraordinary document can have on the average.” Suffice to say, these estimates are speculative, and it will be no small challenge for the Council on Environmental Quality to determine the appropriate cost of a fee commensurate with the administrative burden of a review that has not yet occurred, within 15 days from the date of the application, as required by this bill.

Data on the administrative costs of NEPA preparation are notoriously limited. A similar model of fees for NEPA document preparation exists for the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Committee, which per statute may establish “a fee structure for sponsors of covered projects to reimburse the United States for reasonable costs incurred in conducting environmental reviews and authorizations.” Regulations to implement this provision, which were proposed in the first Trump Administration, didn’t even seek to quantify the full cost of the environmental review and instead chose a flat fee of $200 thousand per project to reimburse only the Permitting Council’s staff costs rather than any cost of the production of the NEPA documents themselves. Those regulations were rescinded by the Biden Administration.

Other agencies have implemented fees for the administrative cost of permitting, including the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) and the Mineral Leasing Act (MLA), both of which authorize cost recovery for costs associated with processing, monitoring, and terminating ROWs. The Forest Service assesses fees to recover the agency’s processing costs for special use applications.

Judiciary Committee Regulatory Matters Subtitle

Another section of potential interest to transportation stakeholders is the Judiciary Committee’s subtitle on regulatory matters, which amends and expands the Congressional Review Act (CRA). In addition to adding various reporting requirements for rulemaking and codifying the role of the GAO in determining whether a rule is subject to the CRA, this provision also inverts and significantly expands the role of Congress with regard to rules that will increase revenues. Rather than just repealing rules under the CRA with a resolution of disapproval, this section would require a vote of Congress to approve a revenue-increasing rule within 60 days, and without that joint resolution of approval the rule would not take effect.

In addition to this prospective authority for new rules that would increase revenues, the subtitle also sets up a five-year process to review every single regulation currently in effect across the federal government. The section requires that each year for the next five years, every agency would select at least 20% of their regulations currently in effect and not previously reviewed, and for each rule, submit a report to Congress detailing the costs, economic impacts, inflationary effects, constitutional basis, and other aspects of the rule. Then Congress would vote whether to approve each rule or not, and unless a joint resolution of approval was passed within 90 days, that rule would cease to have effect.

Potential Challenges for Reconciliation

In the House, Committees’ reconciliation titles must comply with the Committee rules and House rules, and otherwise may include the provisions they choose so long as the committee’s title has a net budgetary effect that complies with the committee’s instruction to increase or reduce the deficit. In the Senate, the committees will face somewhat more complicated procedures, as the bill language must comply with the “Byrd rule”, which prohibits the inclusion of “extraneous” measures. Specifically relevant in this case, extraneous measures include any provision that is outside the jurisdiction of the committee that submitted the title or provision, as well as provisions for which the budgetary effect is merely incidental to the non-budgetary policy change.

Arguably, the HNR Committee’s waiver of all judicial review of environmental documents could be considered the purview of Judiciary Committee in the Senate, though the Environment and Public Works Committee has passed provisions that affect judicial review as part of larger bills in the past. Regardless, since the Judiciary Committee did receive reconciliation instructions, if the Senate determined that the provision fell to the Judiciary Committee, they could still include it in that title. Yet separating the waiver of judicial review from the fees for the document would only further highlight the extent to which the provision is not primarily budgetary in nature, which is the much more likely challenge to be raised in the Senate “Byrd bath”. Even if the policy change did result in $1 billion over the 10-year budget window, as projected by the Committee, the change would have major implications for hundreds of infrastructure and public lands actions and it may be difficult to argue that the fee revenue is the primary goal of the provision.

Similarly, the Judiciary Committee’s five-year CRA look-back proposal would undoubtedly have budgetary implications, but it’s nearly impossible to know what those budgetary implications would be without knowing how Congress will vote on each resolution of approval. Certainly, the implications for regulatory policy exceed the implications for the budget associated with the $10 million appropriated to the Office of Management and Budget to carry out the section, and therefore it seems likely that opponents of this provision in the Senate will have a strong argument that the budgetary effects are merely incidental to the policy changes.

Funding for Environmental Reviews

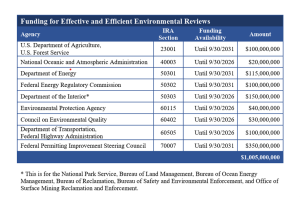

NEPA nerds may also be interested to know the status of the combined $1 billion in funding for environmental reviews that was appropriated under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). This funding was provided across numerous agencies through nine different sections of the IRA, and was intended to enable agencies to expand their environmental review capacity through hiring, technology upgrades and other activities.

Two of the nine provisions have been rescinded in the titles marked up to date, which are the unobligated balances of the $100 million appropriated to the Federal Highway Administration, which was funding the Biden Administration’s NEPA Modernization Challenge, and $100 million appropriated to the Forest Service. The committees of jurisdiction for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) and the Permitting Council have also already marked up their titles and the funding for environmental reviews in those agencies has not been rescinded. The Department of Energy and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission are the jurisdiction of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, whose title has not yet been released.