Jimmy Carter (1977-1981): Transformational Deregulation of America’s Transportation System and More

This article is a part of our series From Lighthouses to Electric Chargers: A Presidential Series on Transportation Innovations

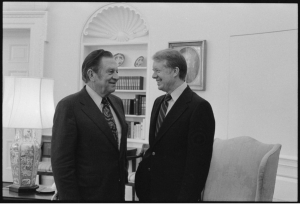

As the policy director for his 1976 presidential election campaign and his Chief White House Domestic Policy Adviser throughout his one term in office, I had the privilege of seeing up-close how the vision, determination, and leadership of President Jimmy Carter transformed in historic and lasting ways the inefficient, expensive, over-regulated American transportation system he inherited into one that today provides greater service at lower costs to the American public, with more jobs, through deregulation of our airlines, trucks, and railroads. This in turn has helped strengthen our economy. Like so many of President Carter’s achievements, the benefits only became clearer after he left office, and he got precious little political bonus for himself.

Eizenstat sitting with the President.

Jimmy Carter’s transportation deregulation was the centerpiece of the most thorough unshackling of American industry from federal regulations in our history, achieving this without compromising health or safety. It included deregulation of crude oil and natural gas prices, which has now made the United States the biggest crude oil producer in the world, and an exporter of natural gas around the world. It also deregulated the beer industry (clearing the way for the enormous proliferation of local craft beers) and telecommunications (sparking the cable era with greater choice and lower prices for Americans.)

Even more broadly, President Carter created the Regulatory Review Council to assure the most cost-effective method was used to accomplish congressional intent and eliminate inconsistent regulations. He established sunset reviews to test whether major regulations were still needed and signed the Regulatory Flexibility Act requiring federal agencies to eliminate unnecessary regulatory burdens on small business. These were not the actions of a traditional Democratic official and showed he was the first “New Democrat” championing the cause of lower and middle income Americans, environmental reforms, civil rights initiatives for women and racial minorities, investments in education, but also adopting cost conscious policies, paving the way for Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. He was a Consumer Populist.

In addition to serving as chairman of his Sumpter County school board, state senator, and governor of Georgia, the Jimmy Carter I knew was also an engineer, farmer, and small businessman, owning and operating a peanut warehouse business. He saw directly how the impact of overregulation negatively affected his own company, with high shipping rates. As he embarked on his marathon run for the presidency, he noted how the airplanes he took around the country were expensive, and seats were only half full. He was determined to bring competition to the airline industry as a first order of business. He made clear in a September 9, 1976, speech at Warm Springs, Georgia, starting his general election campaign, that regulatory reform was also a way of attacking the high inflation he inherited.

As an outsider to Washington, he made the airline industry the first major battlefield for regulation, because it was the most visible to the American people. It was virtually a child of the federal government. As an infant industry in the 1920s, the airlines received subsidies through contracts to carry mail. The precedent was the huge government subsidies to the railroads, giving away millions of acres along the roadbeds that tied together the industrializing nation in the 19th century.

When he embarked on airline deregulation, Jimmy Carter faced an industry in which ten airlines carried more than 90 percent of the nation’s interstate air traffic, but in which prices were far cheaper for intrastate flights in places like California than the costs of comparable flights interstate. From 1969 to 1973, not one new route was approved by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB); it took eight years for Continental Airlines to win CAB approval for a route between San Diego and Denver. Airline seats were limited by an outrageous capacity-control agreement cooked up by several of the airlines; ever-higher fares produced more empty seats than profit, with only 55% of airline seats filled.

In trying to modernize the airline industry by ending anti-consumer regulations, he faced “The Iron Triangle”: regulatory agencies, business and labor which captured these agencies for their own benefit, and congressional committees which oversaw these cozy arrangements. To break the Iron Triangle, Jimmy Carter acted decisively. First, he began by persuading Fred Kahn, a brilliant, charming, and humorous Cornell economics professor and chairman of the New York Public Service Commission, to become chairman of the CAB. Kahn was committed to revolutionizing its relationship with the airline industry, and with a mandate from President Carter, to create a free market, competitive airline industry for the benefit of the flying public, which would end the need for the CAB itself.

Next, President Carter had to deal with his own Secretary of Transportation, Brock Adams, who had been a congressman from Washington state and a supporter of his state’s largest employer, Boeing, an opponent of deregulation. Carter had to dress down Adams to make it clear he strongly supported deregulation and expected Adams to do the same—but Adams still expressed his opposition.

President Carter took full advantage of the support of liberal Senator Ted Kennedy (D-Mass), who had already introduced a sweeping airline deregulation bill before Carter was inaugurated, having been convinced by his brilliant assistant, Harvard Law School professor Steve Breyer and his other aides David Boies and Ken Feinberg, that competition in the airline industry, and beyond, was good for consumers and the economy. To gain press attention, Kennedy’s creative staff organized a hearing they privately called “frozen dog day”—exposing how airlines transported dogs that often-arrived frozen stiff after hours in the cargo hold. All of the airlines testified against Kennedy’s bill, as did its two major unions, and the AFL-CIO, and the CAB itself. Two dazzling star witnesses were Freddie Laker, who pioneered a no-frills, low-cost airline, and Fred Smith, the future CEO of FedEx, who explained federal regulations required him to fly a dozen small planes wing to wing to their destination to avoid CAB oversight.

President Carter and Senator Kennedy at the White House. Source: National Archives

I worked with a real hero of airline deregulation, Mary Schuman on my White House Domestic Policy Staff, then all of 26 years old but as brilliant and savvy as she was charming. She recommended Fred Kahn as CAB chairman and helped us navigate the complex politics on Capitol Hill, in which half a dozen committee chairmen would scrutinize any airline bill, including Nevada Democrat Howard Cannon, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, who was heavily supported by the airlines. Cannon favored only a narrow reform bill to block Kennedy’s broad deregulation bill.

President Carter and Senator Cannon at the White House. Source: National Archives

Kahn at the CAB stretched his legal authority to the breaking point by deregulating air cargo and allowing a second airline to serve Philadelphia. Along with Mary Schuman they went around the country touting the consumer benefits of more airline competition. Mary organized a broad, diverse support group for deregulation with consumer groups, major business and retail companies. She wisely argued that Kennedy’s desire to deregulate at one stroke was a mistake and argued that airlines should get five years to phase in a new, more competitive airline system. Critically, Mary persuaded President Carter and me not to submit a detailed administration bill to avoid angering backers of the competing Cannon and Kennedy bills, but to release a presidential message outlining general principles guiding legislation, while she would serve as midwife of a compromise bill. She later mused that it helped that she fell in love with one of Kennedy’s top aides, David Boies, and they eventually married. But we all faced a phalanx of airline and union lobbyists.

Over 18 drafting sessions and tough negotiations, Mary, along with Simon Lazarus, another member of my staff, and I forged a compromise of the Kennedy and Cannon bills, which passed the Senate, but almost crashed in the House before being salvaged and signed into law. Success demonstrated that a determined President (Carter), a gifted regulator (Kahn), and highly creative and indefatigable staffers (Schuman in the White House, and Breyer and Boies in the Senate) could break ingrained Washington interests for the benefit of the public.

Carter signing the Airline Deregulation Act in October 1978

Carter’s deregulation democratized air travel, making it affordable for the middle class. The number of airline passengers on US airlines leaped from 197 million in 1974 to 862 million in 2023. Before Carter’s victory only one-quarter of the public had ever flown; in 2024, 90 percent had flown. Fears that small towns would suffer under deregulation were unfounded. A 1996 study by the U.S. General Accounting Office found more than half of small and medium-size markets had more flights than before deregulation. And fares, as measured in inflation-adjusted dollars, have dropped. In short, air travel has dramatically increased, and fares have fallen as a result of President Carter’s deregulation.

Exhausted by our success with airline deregulation and bruising energy battles, President Carter presided over a contentious debate in the Roosevelt Room of the West Wing, just across from the Oval Office, about whether to deregulate the trucking industry, as well. I argued against it: we should take our victory on airlines, and not take on the thousands of trucking firms and the rough and powerful International Brotherhood of Teamsters union. But fortunately, for our country, President Carter was determined to transform America’s entire transportation system.

Trucking was inextricably linked to the railroads in the nation’s integrated system for moving freight, and both industries were tightly regulated by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). As with Fred Kahn at the CAB, President Carter appointed Darius Gaskins, Kahn’s chief economist, the ICC’s first black chairman, and a strong proponent of deregulation.

Our strategy was to propose a deregulation package covering both trucking and rail, with President Carter’s message on railroads going first in March 1979, to Congress because he warned that without changes, the country would face catastrophic railroad bankruptcies, like Penn Central. Although it was not easy to enact a revolutionary change in railroad operations and pricing, with opposition from the coal companies and their electric utility customers, we were able win in only half a year, with the president signing the railroad deregulation law only three weeks before the 1980 presidential election. Railroads could now set prices and manage their businesses without ICC interference, and could more easily abandon unprofitable lines, but with protections for workers dislocated by the changes. In words not typically found in the lexicon of a Democratic President, Jimmy Carter said, this act is “is the capstone of my own efforts to get rid of needless and burdensome Federal regulations which benefit nobody and which harm all of us.”

Trucking was an entirely different and more intense battle, with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters as the immovable object; they had organized about half the workforce of the regulated trucking companies and correctly regarded deregulation as an existential threat. When the Teamsters learned of the president’s determination to deregulate trucking, Frank Fitzsimmons (successor as Teamsters President to Jimmy Hoffa, who had mysteriously disappeared and was believed murdered), asked me to come to his office near Capitol Hill for what he said would be a one-on-one meeting. Instead, I was ushered into their giant conference room where the regional Teamsters presidents from the industrial Midwest were arrayed against me, as if I was facing the front line of the Chicago Bears alone. My goal was to get out alive, theirs was to signal their strong opposition to deregulation. I emphasized we were genuinely interested in their views, and we did host the Teamsters union staff at the White House.

The Teamsters feared deregulation would weaken the regulated trucking firms they had organized, in favor of non-union drivers who were independent contractors. They also feared big firms would undercut small ones with predatory pricing, driving them out of business, and leaving the remaining firms facing less competition. They were willing to be flexible on rates, but only if our bill contained job and safety protections for the drivers. The trucking companies were equally opposed to deregulation, ending their protected cocoon. They also had a special immunity from anti-trust laws.

But the ICC for decades passed along large union pay increases to the public in the form of higher rates, which in turn were buried in everyday prices of goods at the supermarket or department store. No regulation was more pernicious and costly than the ICC’s “backhaul” rule, which forbade trucks carrying products from one city to another, to pick-up a new load and take it back; the trucks had to come home empty! In June 1979, President Carter sent a powerful message to Congress seeking legislation that would free the economy from a “mindless scheme of unnecessary government interference and control” that “contributes to three of the nation’s most pressing problems—inflation, excessive government regulation, and the shortage of energy.” Our proposed legislation would immediately remove the ICC’s route and price restrictions, the industry’s antitrust exemption, and abolish rate bureaus as “price fixing which is normally a felony.”

As with airline deregulation, Senator Kennedy was an indispensable ally, shielding us from attacks by congressional Democrats that Carter was anti-union. We got an unexpected break when Senator Howard Cannon, chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee, was investigated by a federal grand jury for allegedly taking Teamster campaign contributions in return for sponsoring a weaker bill. While he was ultimately not charged (and I submitted an affidavit on his behalf), it led him to support the tougher deregulation bill being promoted by Carter and Kennedy.

President Carter stood firm against intense lobbying to weaken his bill in either the Senate or House and in 1980, the Motor Carrier Act gave him most of the reforms he sought. Independent studies showed the benefits of trucking deregulation are staggering and flow throughout the economy: dramatically lower rates, entry of new firms, and reduction in the cost of inventories because of quicker and more flexible delivery times. Fred Smith, the CEO of FedEx noted President Carter’s “unappreciated leadership” in these words: “The reduction of logistics costs in the late 20th century was profound, largely unreported and underappreciated. These farsighted changes were the great achievement of the Carter presidency.”

One negative prediction has unfortunately been borne out: with the entry of less expensive, non-union carriers, the biggest loser was indeed the Teamsters union workers. The percentage of unionized truckers in the first five years of the new law fell from 60 percent to only 28 percent.

There were political ramifications. Although there were several reasons, historically Democratic blue-collar workers became Reagan Republicans in the 1980 presidential election. Still, by any economic measure, deregulation of America’s transportation industry made it and the American economy more competitive with great savings to the American consumer. (We also proposed deregulation of interstate buses but ran out of time; it was passed in the Reagan administration).

President Carter’s deregulation of all major modes of transportation would be a historic accomplishment in itself. But it does not stand alone. He deregulated the price of natural gas and crude oil, creating the foundation of the energy security the U.S. enjoys today. His deregulation of telecommunications led the way to freeing electronics for competition and innovation, the erosion of the long-distance monopoly of telephone service by AT&T, and the deregulation of interest that banks could offer customers.

Former Republican Senator Phil Gramm summarized the impact in a Wall Street Journal op-ed article on President Carter’s 100th birthday: “Without Mr. Carter’s deregulation of airlines, trucking, railroads energy and communications, America might not have had the ability to diversify its economy and lead the world in high-tech development when our postwar domination of manufacturing ended in the late 1970s. The Carter deregulation helped fuel the Reagan economic renaissance and continues to make possible the powerful innovations that remake our world.”

About the author

Stuart E. Eizenstat served as Chief White House Domestic Policy Adviser to President Carter; U.S. Ambassador to the European Union; Under Secretary of Commerce for International Trade; Under Secretary of State for Economic, Business and Agricultural Affairs; and Deputy Secretary of the Treasury in the Clinton administration. He is currently Senior Counsel in Covington & Burling LLP’s international practice, and is writing this in his private capacity.

He is also the author of the book “President Carter: The White House Years,” as well as “Imperfect Justice: Looted Assets, Slave Labor, and the Unfinished Business of World War II” and “The Art of Diplomacy: How American Negotiators Reached Historic Agreements that Changed the World.”