March 3, 2017

This week, participants in the Eno Center for Transportation’s Transit Senior Executive Program heard from Masaki Ogata, Executive Vice Chairman of East Japan Railway Company (JR East) and President of the International Association of Public Transport (UITP) about the challenges of operating a transit agency in the 21st Century.

Eno Transportation Weekly sat down with Mr. Ogata afterwards for a wide-ranging interview about Japanese transit operations, the future of mobility, and his career in transportation.

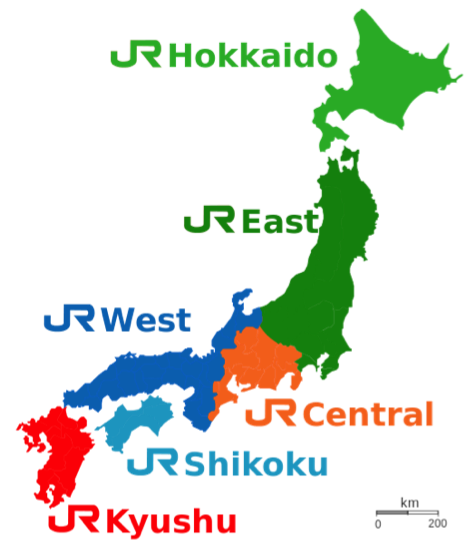

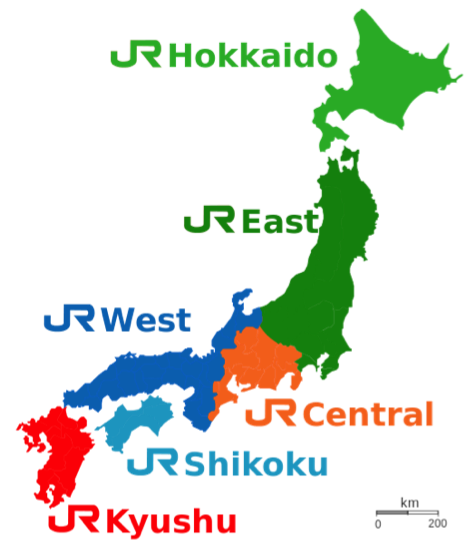

As background, JR East is part of the Japanese Railways Group (JR Group), comprised of seven for-profit companies. Following the dissolution of the government-owned Japanese National Railways in 1987, JRE was one of the railways to take over the assets and operations of Japanese National Railways.

JR East now has full private ownership – similar to JR Central and JR West – but is still discussed in contrast with “private railways” since it inherited a part of the “national railway” network. It is headquartered in Tokyo and serves 17 million passengers per day.

(The interview has been edited for clarity)

ETW: What motivated you to enter the transportation sector?

MO: When I was at university 43 years ago, I had no intention of entering transportation. To be honest, my good friend who had worked with me had a family member working for Japanese National Railways (JNR). He was a high level executive member and he insisted that I work there.

I was amazed – it’s a huge entity and it has a big effect on the daily lives of all Japanese people. At the time it covered all of Japan. And also, at the same time, it is now a conglomeration of former Japanese railways. Even at a very young age from my entry into the company, people like me were in high positions at very young age.

And, from a young age, I was very responsible for large things.

ETW: What were the high points of your career and what shaped your life as a young professional?

MO: My background is in engineering. I was put into various different departments, but one highlight was the moment I when I became the chief of a depot. I was in charge of management for 600 people at the age of 28.

Of course, there were 20 vice managers; they were older than me, almost by 20 years. This is very tough work because I had to face the very strong labor unions at the time.

ETW: How did you deal with being the younger person in this role?

MO: At the time the environment was very different. A reason the former JNR went bankrupt is mismanagement and the very, very bad labor relations.

The labor unions were very big. My management was talking to the labor unions – but they were friends and they were often from the same hometown. My experience was that I had to do this – to oversee the operation and take responsibility for it – on my own. I had to rely on myself.

ETW: What did you find were the best methods for negotiating with labor unions?

MO: Communication is very, very important.

After that era, I was assigned to public relations. The former JNR had a lot of critical issues. By this I mean the opinions of the Japanese media. At the time, every newspaper – whether it was from A-Z – no day went without [them publishing] criticism of JNR.

So I was assigned to the PR department. There were days of failure, days of agony… but I experienced a lot. That made me a lot stronger. I was not the director of the PR department because I was very young, but I was the contact person. So all the phone calls came to me. All of the inquires came to me. I just have to locate this information to main departments. I had to answer.

ETW: The media can certainly be aggressive when pursuing stories – how did you mitigate that? How did you interact with reporters?

MO: As with the former case with the unions, communication is very important. Patience is also very important.

To get angry is worth nothing.

To have a shorter temper in front of them is nothing.

To communicate with our staff member, who is paid by the same company, we are in the same vessel.

Journalists are paid by other companies. But of course, we have to communicate. So I had to be patient. Even though they get angry, I had to be very calm. And so all the time I might just frown a lot, but I would never get angry. I would always calm down.

GR: What would you like to accomplish while you’re president of UITP?

MO: We have 19 countries and 1,400 agencies. This is a good arena for all of the players, as I want to try for all of the members of UITP to communicate.

On the other hand, I emphasize innovation – just as I emphasized in today’s speech to Eno’s class as well. Even though innovation is important, if you cannot communicate very well, it doesn’t matter.

Like what you do at Eno, communications and PR is very important to persuade the people, to inform the people of what we are doing. To inform different people of what you’re thinking… two-way communication is very important for the human being. It is not a fight. It is a communication.

We have to understand them, they have to understand us. That’s why we try to make ties with what we are thinking and what we are debating.

ETW: That’s the challenge of the media – everyone sees the headlines before (or perhaps instead of) the actual stories. In that sense, how do you interact with different stakeholders at JR East?

MO: These various stakeholders are very important. Again, we have to communicate with the various types of stakeholders.

The customer is very important of course, and the investor as well. Sometimes local government, sometimes central government, in terms of subsidies. In all of these cases, communication is very important. But today, we are surrounded by a rapidly changing environment. I think that the social, economic environment has rapidly changed.

For example, Japanese markets are shrinking. Japan is a leader, top-runner in the Asian society. Japanese corporations are degrading very rapidly and we have to stop it. And the aging society is growing, of course.

Today, many critical issues are expanding instantly to Japan, whether they are political or economic.

In Japan we also have to be careful about natural disasters, this is caused maybe by CO2 emissions and climate change. So we have many, many critical issues surrounding us. So our challenge is adaptation. We have to innovate, we have to change.

ETW: On that note, was JR East affected by the tsunami in 2011?

MO: Yes, that happened in our area, the northeast, so that is definitely our territory. Wesuffered a great earthquake in March 2011 – nearly six years ago – and people are still trying to recover. Some areas are almost completely recovered, but still many people have suffered the effects of the tsunami and the earthquake.

ETW: What sort of preparations does JR take for situations like that? Are there emergency funds and/or contingency plans?

MO: Oh yes, certainly.

ETW: Looking at NYC with Hurricane Sandy, how can cities like NYC learn from what JR East has done?

MO: My background is also in safety. I have continued to be in charge of safety at my company. Investment is very important, besides the culture. Safety culture is important, and employee behavior is too.

However, investment is very important. Since 1987, we have invested a lot in safety. It went up to 3 trillion yen, which is about 30 billion USD, for the past 30 years. Included among safety are measures for natural disasters. We have already announced that 3 billion U.S. dollars have been invested after the earthquake. So we have continuously invested for natural disasters.

This was never happened during the years of JNR. So now we have very good preparations. But today, after privatization, JR East prepares for the worst.

Prepare for the worst is a key approach for us. We have not had another natural disaster yet, but we always prepare for that.

So actually, we just checked some statistics and my very rough estimate is that when we prepare for the worst, it halves the cost of the natural disaster. When we don’t, the cost is double. So preparation is very important.

ETW: With the Tokyo 2020 Olympics coming up, you’re looking at a huge spike in demand – in addition to your 17 million passengers per day. Do you have any estimates of what the Olympics will look like?

MO: 2020 is just three years away, but in Japan, we already have established a very dense network.

Of course, somewhere we have to adjust things, but for the network itself, we have already established it. Asyou can imagine, this kind of spike in demand might occur, for example, in a very special hour in the day, or a day in a week during the games.

In this case, maybe we better have some advocacy for the commuting people, or some very good management of the traffic of the people. For example, even though our network has been established in the past years, we are modifying our stations and facilities to allow for a smoother movement of the people who get on and off the train, especially near the stadium of the Olympic games.

There are many stadiums for the Olympic games. They’re located all over Japan, mainly in Tokyo, or located right out of Tokyo. Now we establish our stations to fit for the movement of people.

ETW: Other cities that hosted the Olympics have encouraged people to work from home to leave room on transit. This brings us to an interesting point – your focus is clearly on communication first, innovation second. I’m aware that Japan is really focusing on putting autonomous vehicles on the road for the games.

Do you feel that the advent of autonomous vehicles (AVs) is going to impact your business at all, or just a complement to what you’re already doing?

MO: We can expect a lot of movement during the games, from both Japan and around the world. Right now we are not so interested in AVs.

Of course we have to do that, but for the games we have to have better management for the people’s movement. For the safety, security, it is very important. And before the games in 2020, fortunately Japan is enjoying increasing foreign tourism.

In order to do that, Japan needs many more hotels – today we have a shortage of hotels. So, the government is trying to expand accommodations. We have to prepare everything: lodgings, accommodations, and transportation.

We are the rail company, but also we have many hotels and other facilities. So anyway, we can expect many things.

ETW: What would you recommend to transit agencies in the US who don’t have the same opportunities afforded to them to bridge the gap in their budget shortfalls? Government funds are decreasing, and ultimately our government is becoming less and less supportive of public transit. What would you say to these American transit agencies? How can they find sources to fund them?

MO: It is a very good thing from our point of view to stand alone, if it is possible.

In that case, the transit agencies have to deregulate the constraints surrounding them. If a second business – such as establishing a retail or shopping center [that would be owned by their agency] is constrained by the regulation, they need to better advocate for subsidies – or deregulation.

In Japan as well, when we started these businesses, many protests against came from the cities, they thought JR was too big and they were afraid that our shopping centers might affect other businesses. However, finally we did it. Service in the United States is not so bad though.

In Japan, we don’t get any subsidies from the central government after privatization. It is a very good thing. But on the other hand, if it is a policy of the local government, subsidy itself is not so bad.

If they decided it that way, it’s okay. If there exists the concept of a public subsidy/service obligations (PSO), it is alright. The people need [to have transportation options]. But generally, it is very good of the government to receive the tax than pay the subsidy.

ETW: Serving the public can be a matter of serving the customer. Since we’re looking at many new technologies in the next decades including AVs, drones, and even virtual reality, how can JR stay competitive as people’s interactions with space and time are changing?

MO: Fortunately in Japan, we’re in a very good position, especially in Tokyo.

Our railroad network is very dense and has very good connections to the rest of the company. In Tokyo, the rail is very near to air and water – it is a basic, fundamental thing.

However, you are right. I think that Tokyo itself is okay, even though these technologies are coming.

In Tokyo, people will walk 1 or 2 km instead of taking the train. They try to be healthy. So some people just decide to walk. But we have to innovate, even though we are in such a condition. We have to believe that people will choose the optimal route, shortest total trip time.

The age of this model will soon come. In this case, the first and last mile will be a very key factor, and the transfer station, which we call a node in Japan, will also matter. But one minute is one minute. We need to reduce transfer time within stations and between modes. The first and last mile time has to be reduced too. We have to integrate with modes like Uber.

ETW: Are you partnering with Uber or Lyft in any way?

MO: Not yet. In Japan, maybe due to regulation, Uber and Lyft have not yet appeared [in a significant way].

It will change in the future though. The taxis are against it though, and the department of transportation is conventional. But it will increase in Japan eventually. At the same time, Tokyo is a very special city. I think that, temporarily, people don’t need Uber so much.

ETW: It seems that there is a concentration focused on active transportation.

MO: We’ve always enjoyed a sharing economy, and car-sharing has already increased in Japan. In my age, 50 years ago, I was always dreaming about the new car. The new Toyota, I said!

But today, they’re not interested at all. It is very easy for them to share.

(Interview conducted by Greg Rogers and transcribed by Jenna Fortunati.)