March 3, 2017

One of the issues that has recently surfaced regarding air traffic control (ATC) reform is how to introduce, if possible at all, competition in any eventual reform efforts.

First, a little bit of background: ATC is usually divided into two different sorts of service, en-route and terminal.

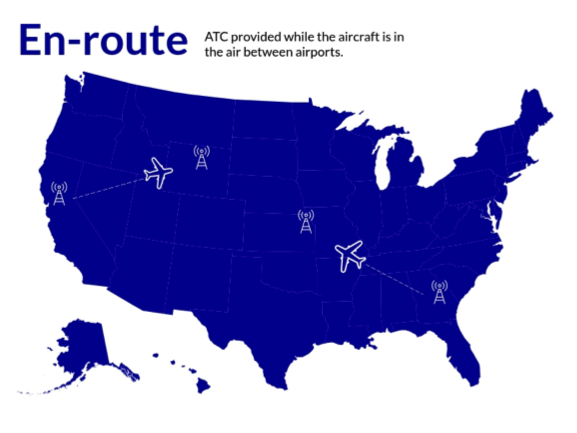

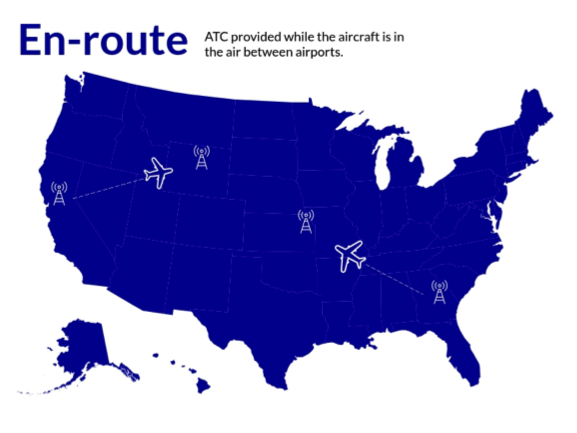

En-route is ATC provided while the aircraft is traveling in the air between airports.

Terminal is ATC provided for landings and departures, and while at an airport.

This distinction is important because while en-route services are usually considered a natural monopoly, i.e., a service where having only one provider is the most efficient way. For terminal services, that is not necessarily true.

In the U.S., the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) currently operates both en-route services, where it has a monopoly, and terminal services, where it operates roughly half of the 500 airport towers in operation in the country. The remaining half of the towers are operated by private companies under the FAA’s Contract Tower Program. This program was created in the 1980s to provide ATC services at low-activity airports. Those towers are contracted out in three different blocks for a period of around five years at a time.

The companies RVA, Midwest, and Serco won the current three concessions. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Office of the Inspector General, contract towers are safe and “cost-effective,” averaging $537,000 per year to operate compared to $2.025 million for an FAA tower. Most of the reduction in costs comes from the lower labor requirements for these towers compared to FAA towers, as well as lower salaries paid to controllers. Overall the Contract Tower Program costs around $150 million per year.

Obviously, since the U.S. already contracts out terminal services at hundreds of airports on a concession basis, terminal services are where it would be easiest to introduce market forces for ATC provision. In some countries, like the United Kingdom, the market for airport ATC operations is completely liberalized, with each airport having the right to either provide its own ATC services or to contract them out. For example, at London’s Gatwick airport, ATC is provided by DFS, the (government-owned) German ATC provider. Contracting out airport towers is thus the easiest way to introduce competition in ATC.

For en-route services, on the other hand, while competition is theoretically possible, there are a number of challenges that can potentially arise if an atmosphere of competition is sought. Since there is a general agreement that en-route services are a natural monopoly, competition can only be introduced systemwide, at discrete points in time. For example, the U.S. could run an auction to provide ATC services for the entire country. This was done in the United Kingdom in the early 2000s, and the winner paid £758 million (USD $940 million) for 46% of NATS, the UK provider (the government kept 49% and the remaining 5% was sold to employees).

While such an auction would introduce competition, that would only last until an auction winner was found. However, to introduce further competition, a contract could last a set period of time, and a competitive auction could occur at intervals consistent with the useful lives of major investments. This could bring new players into the market, helping to encourage efficiency and improvements. On the other hand, auctions have costs, might be disruptive for operations, and also can create disincentives for long-term investments.

Since the auction winner would have no competition once operation began, some sort of economic regulation of its activities would be needed. However, economic regulation has the risk of being overly burdensome and could discourage private interest in system operation. On the other hand, if little or no economic regulation is imposed, the public interest could be put at risk. The private corporation would likely aim to maximize its profits and shareholder value, and without some level of oversight, it could disregard the growth of the system or other areas of public interest.

While there is a possibility of approaching ATC reform this way in the U.S., this is mostly an academic conversation. As far as we at Eno are aware, no one has really put forward any proposals that would reform this system this way, either by auctioning off en-route services, or by allowing each airport to have the independence to decide how to provide its ATC services.

Additionally, several stakeholders that support efforts to spin ATC off into a nonprofit entity (namely air traffic controllers) have opposed any efforts to introduce for-profit motives into ATC provision. Because of this, both the practical and political realities seem to suggest that the introduction of significant economic competition into ATC provision is not something that is politically realistic for the United States.

For more on the issue of ATC reform see our most recent report on the issue, Time for Reform: Delivering Modern Air Traffic Control, as well as our FAA Reform Reference Page.