Intercity Bus Service: An Additional View

As the Trump Administration and Congress review and critique the funding and policies contained in the 2021 Infrastructure Bill, transportation advocates should expect a renewed focus on federalism; focusing federal dollars on truly national programs, and cutting waste. The rural intercity bus program, known as 5311(f), stands out as a positive example of a low-cost, high-return FTA program. With authorized annual funding at about $137 million per year under the Infrastructure Bill, the intercity bus program addresses interstate transportation needs in America’s Heartland at a tiny fraction of the subsidies to passenger rail and public transportation. The program funds limited gaps in an otherwise successful, unsubsidized and highly-competitive privately-operated network. More FTA, State DOT, and urban transit agency attention to this program could make it even more effective.

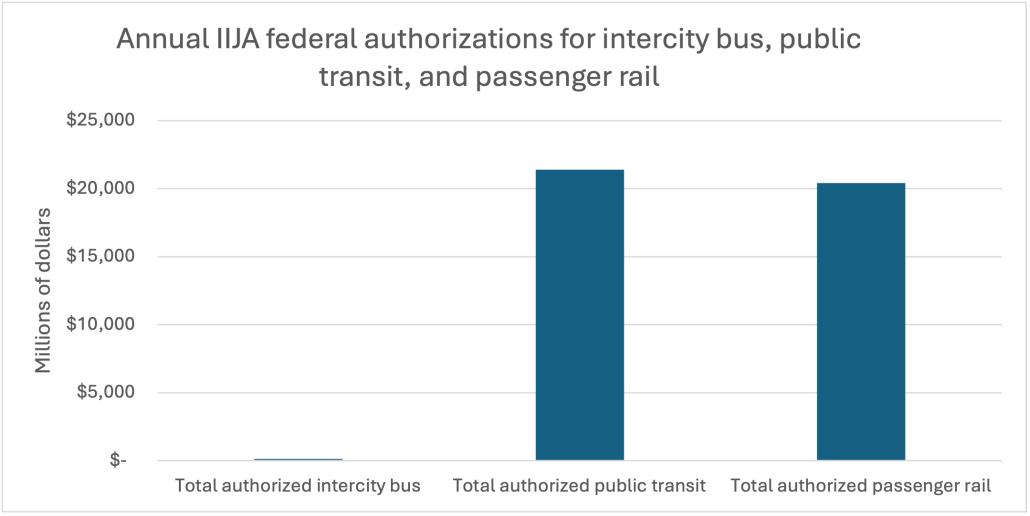

In contrast to intercity bus, federal subsidies to Amtrak and public transportation, which serve primarily the Nation’s largest urban areas, have ballooned shockingly over the last decade, while support for interstate services in the Heartland have remained infinitesimal. Under the IIJA, total authorized funding for intercity rail passenger transportation and public transit exceeded $100 billion, each. That is a $90 billion increase for passenger rail and a $40 billion increase for public transportation between the FAST Act and the IIJA. Yet authorized funding for rural intercity bus, the backbone of intercity Heartland services, has remained a rounding error at less than ⅓ of 1% of passenger rail and public transportation. Even rural local transit subsidies are almost six times more than intercity bus support.

Like most surface transportation programs, the intercity bus program is a federally-assisted, state-delivered program. The varying interests and priorities of State DOTs and FTA’s level-of-interest can lead to success or failure. Clear direction from FTA should guide States to focus on the program’s purposes, which are (1) to provide service in corridors where unsubsidized services do not exist, but where demand for that service remains; and (2) to make meaningful scheduled connections to the unsubsidized national bus network. The goal of the program is not to simply subsidize “better medium-distance bus service for rural Americans”, which could be implied to create subsidized competition in existing, unsubsidized corridors.

Although not a current program requirement, FTA could also encourage States to partner more with each other to support interstate connectivity, including joint 5311(f) routes across State lines. Finally, FTA should enforce existing laws with its urban transit grantees, which require them to provide “reasonable access” to intercity buses in their transportation centers at reasonable costs. Many transit centers do accommodate intercity bus, while some refuse access or ignore requests for private bus operators. Connections at intermodal hubs are crucial for Heartland communities.

Most States have excellent programs, but those that fail to implement the program successfully do so for three main reasons: (1) they subsidize duplicative intercity services that compete in substantial part with existing unsubsidized services, (2) they transfer the rural intercity bus service funding for rural transit, not intercity bus, purposes and/or (3) they fund services that don’t make meaningful scheduled connections to the unsubsidized national bus network.

Examples abound where States have gotten it right. Washington State and Oregon are examples of states that have built excellent, integrated, subsidized and unsubsidized services into a statewide and interstate network that fills gaps in the unsubsidized intercity bus network, but does not seek to replace that network. Yet there are also examples of States that improperly use their subsidies to drive unsubsidized intercity bus services from the marketplace in key corridors or simply fund rural intercity bus routes that are not connected to interstate destinations. FTA should halt such practices, which impact the viability of the privately-operated network far beyond the contested corridor.

Going forward, while the intercity bus program is a cost-effective, efficient, interstate program, it has potential to better serve the Heartland. These are some critical issues to address:

- Is there a structural imbalance between funding for Amtrak and local transit on the one hand and intercity bus service on the other? If so, how best to address this imbalance?

- How best to work with the private sector to expand intercity bus services in the Heartland without damaging unsubsidized intercity services?

- How to create timely FTA enforcement mechanisms to ensure that states plan and implement cost-effective intercity bus programs that meet Federal objectives?

- How best to structure federal interstate transportation funding to integrate interstate and local transportation services into a network of intermodal hubs providing seamless connections, with a particular focus on tying rural communities into that network?

Gregory Cohen, P.E. is a former State DOT transportation engineer and planner, served on the professional staff of the Committee on Transportation & Infrastructure, U.S. House of Representatives; and currently serves as a government affairs consultant to transportation companies and non-profit associations. He is a 1999 Eno Transportation Center LDC Fellow.