November 16, 2016

In a new study published on November 15, the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Transportation (IG) reported on NextGen deployment. NextGen is the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) program to modernize air traffic control (ATC). Titled “Total Costs, Schedules, and Benefits of FAA’s NextGen Transformational Programs Remains Uncertain”, this report is a follow-up of another report from 2012 on the same subject.

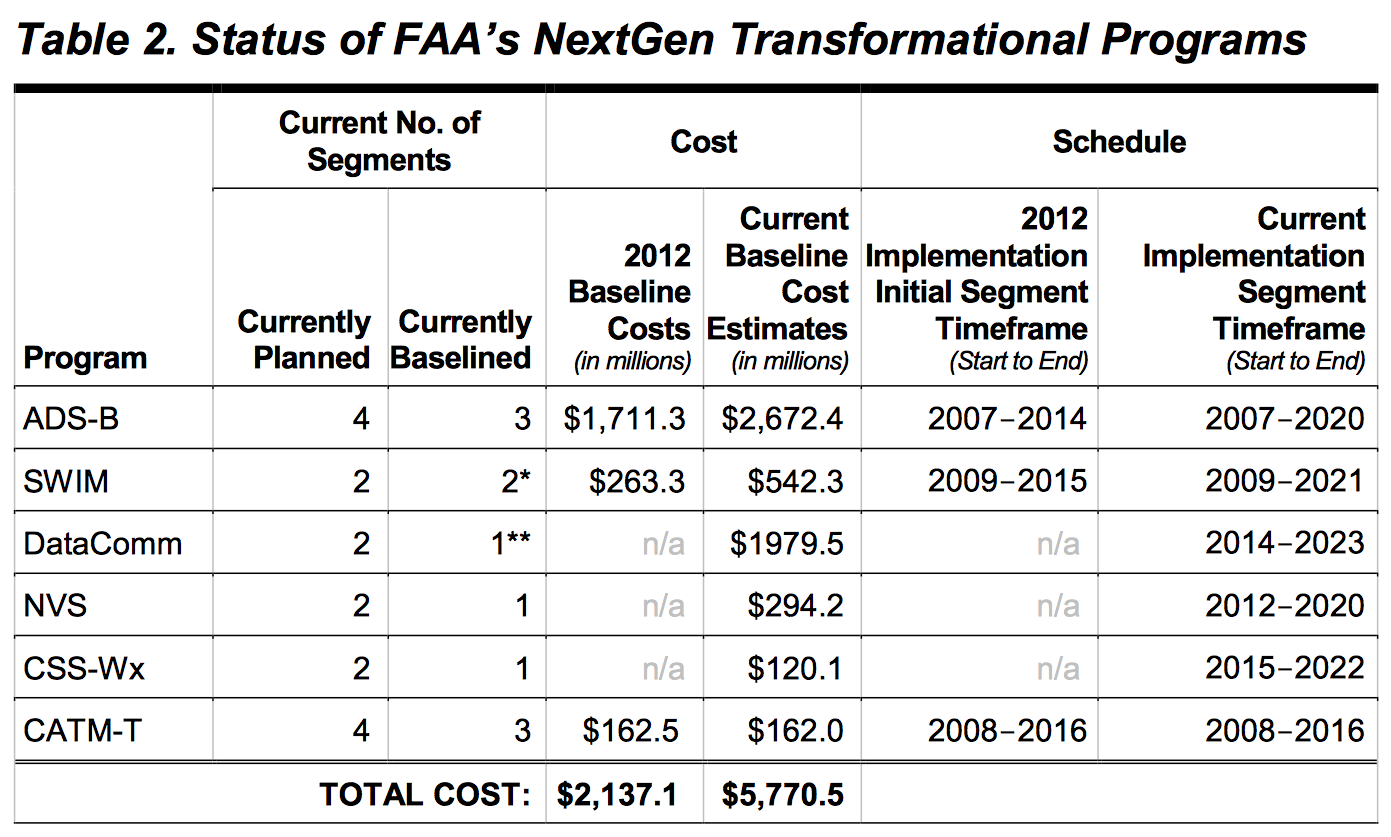

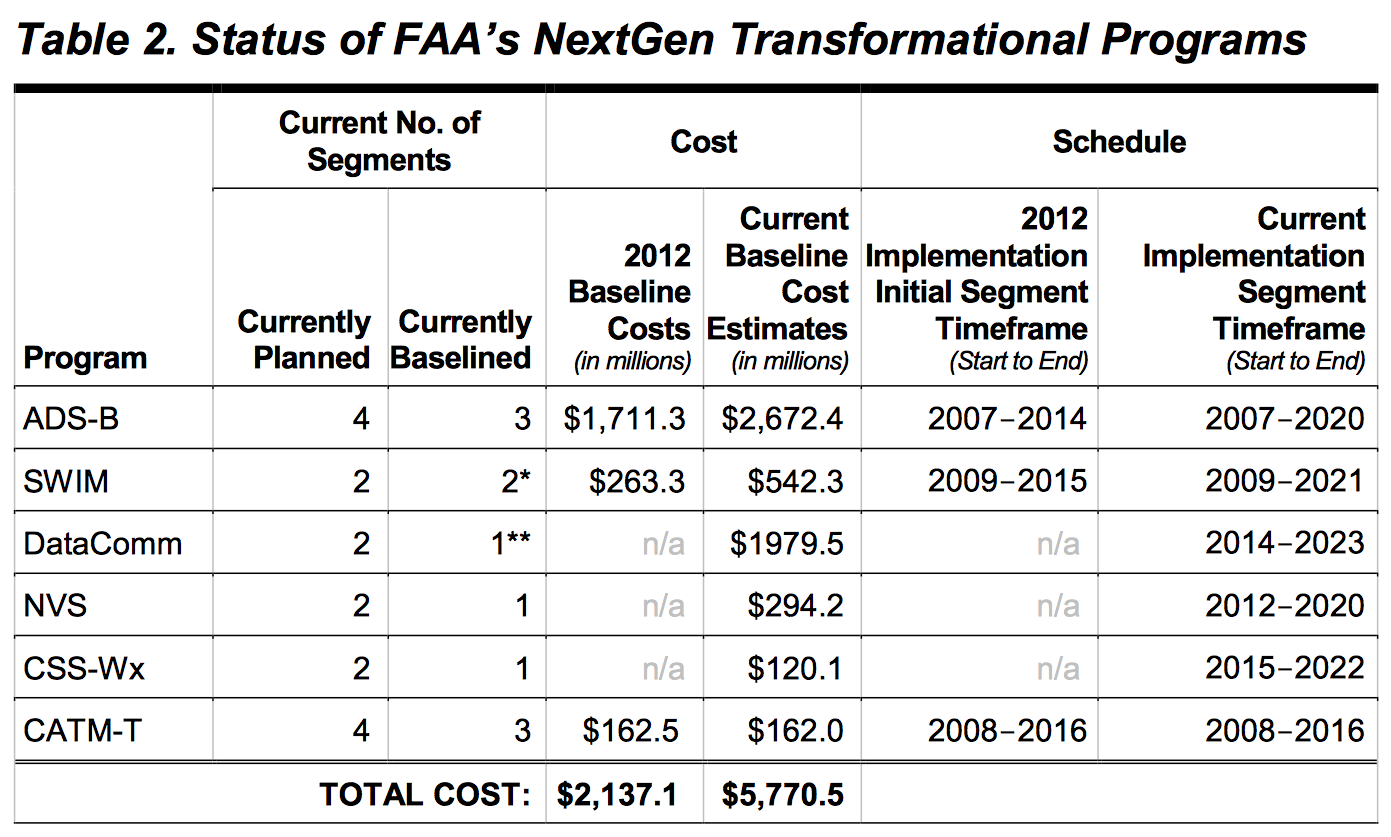

The report aimed to ascertain what adjustments has the FAA made to key projects, including schedules and costs, as well as expected benefits. The focus was on six key NextGen projects:

- Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B), to replace radar-based navigation with satellite-based navigation.

- System Wide Information Management (SWIM), to improve data sharing between the agency and airspace users.

- Data Communications (DataComm), to allow controllers to talk to pilots via text message instead of voice.

- NAS Voice System (NVS), to replace analog voice communication with digital.

- Common Support Services – Weather (CSS-Wx), to replace current weather information distribution systems.

- Collaborative Air Traffic Management Technologies (CATM-T), to improve the efficiency of traffic management.

Since 2007, the FAA has invested over $3 billion in these NextGen initiatives, with total planned costs through 2020 being $5.7 billion. (In total, the IG noted in a letter in September, that investment in NextGen had totaled $7.4 billion since 2003, the year the program was launched.)

Overall, the IG concluded that the FAA has not “fully identified the total [emphasis in the original] costs, planned segments, their capabilities, or schedules”. Also, the FAA has not completed the requirements for some of these programs, and keeping key investments decisions on track remains a challenge for the agency. The breakdown of these projects into smaller segments, while allowing the agency to better manage the projects, has the drawback of limiting FAA’s ability to accurately and consistently measure the progress of a program. This breakdown also means that the programs don’t have an end in sight: as more technologies become available, the program is restructured to include them, and segments are readjusted. This make accountability more difficult, both in terms of overall program costs, and in assessing the realization of benefits.

In terms of the benefits that these programs will bring, the FAA has not updated the expected benefits since the last time the IG looked at the issue in 2012. This is despite increasing costs and delayed deployment for all the initiatives, except for DataComm, whose deployment is now anticipated several years ahead of schedule (the other programs have delayed on average five years). They have also failed to quantify benefits for some of the programs, and have also not disclosed when benefits will start to be delivered. This has consequences in terms of equipage by the airspace users – both commercial airlines and private pilots. Without concrete benefits, airspace users do not have economic incentives to equip their aircraft with the necessary equipment to use NextGen technologies, creating a situation where NextGen does not deliver because users are not equipped, and users do not equip because NextGen does not deliver them benefits.

Finally, the IG states that is hard to determine how “transformational” these programs will be, as in the beginning they mostly provide incremental improvements, and in the long run expected benefits have not been determined yet. Additionally, most of the NextGen programs are now simple infrastructure programs to bring the system up-to-date with current technologies, but, unlike what was initially envisioned for NextGen, will not fundamentally change the way air traffic is managed.

Eno has been researching and discussing issues around ATC governance, funding, and modernization for several years now, and we’ve compiled all related information (including our 2015 report on ATC reform) in our FAA Reform Reference Page.