Improved Data Collection and Analysis Is Key to Better Decisionmaking

The act creating the Department of Transportation in 1966 tasked the new department with the duty to “promote and undertake development, collection, and dissemination of technological, statistical, economic, and other information relevant to domestic and international transportation…”

The new department was formed from a hodgepodge of previously existing agencies and parts of agencies, some of which were already gathering and reporting statistics on their modes of transportation. At what is now the Federal Highway Administration, information gathering and publishing on roads was part of its core mission since its foundation as the Office of Road Inquiry in 1895.

The transportation regulatory commissions (the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) and the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB)) kept and published extensive data on rail, motor carrier, pipeline, and air routes, traffic, and costs, because without that information, they could not adequately regulate fares and service. Some of that responsibility was transferred from CAB and ICC to DOT at DOT’s creation, while other authority was transferred later when airlines were deregulated. But for other modes of transportation, there was little data being collected, and there was no attempt at all to synthesize information across modes or publish any intermodal data .

From the start, both the Congressional appetite and administrative capacity for producing comprehensive cross-modal information about national transportation has been intermittent. The very first DOT Appropriations Act (for FY 1968) appropriated $5.95 million to the Secretary to conduct research, including the collection of national transportation statistics,” and its report language urged DOT to better organize and prioritize its information and statistical functions. This was not done, so Congress followed up in the report on the fiscal 1969 funding bill, demanding a report on the Department’s future plans in this area and the budget and manpower needs for carrying that out.

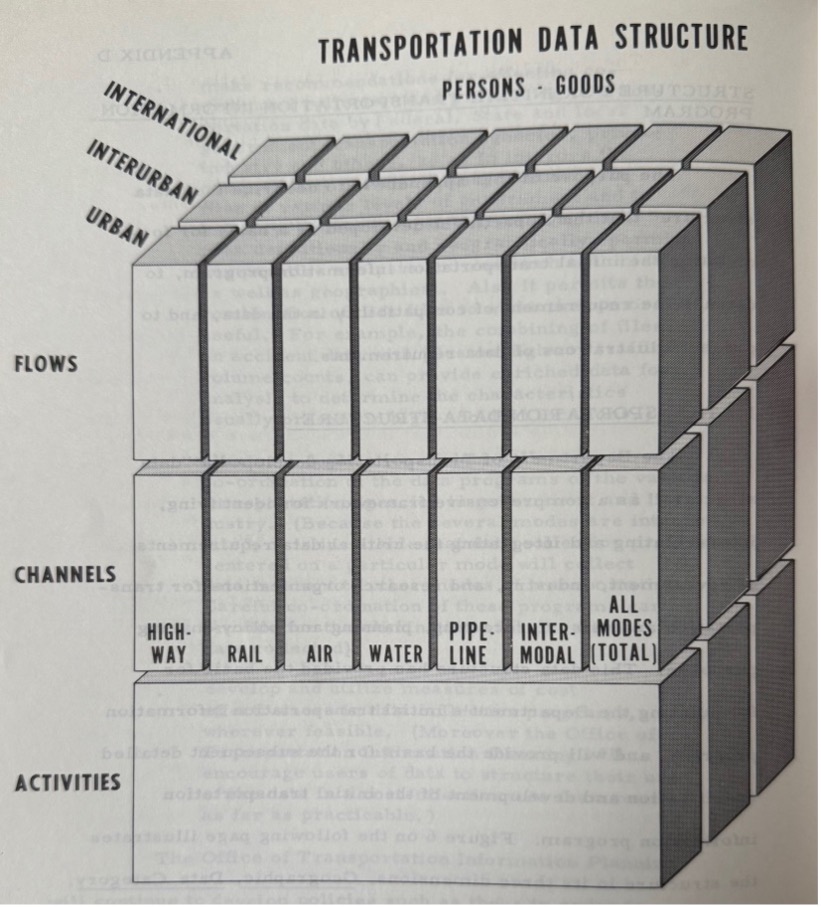

The result was a 260-page document we called the “Red Book” published in May 1969, which gave comprehensive statement of national transportation data requirements and a design for achieving it proposing a five year program of $26 million starting in 1970. Yet despite our pride in this document, Congress never responded and never added funding.

TRANSPORTATION INFORMATION A report to the Committee on Appropriations, U.S. House of Representatives from the Secretary of Transportation May 1969

The first attempt in the Department’s history to actually produce a collection of national transportation statistics was prepared in 1977 for the Department’s 4th Secretary, William T. Coleman. Entitled National Transportation: Trends and Choices (to the Year 2000), it was dubbed the first comprehensive national perspective on transportation since the Gallatin report to President Thomas Jefferson.

Similar comprehensive efforts have occurred since then from time to time, starting with the work of the National Transportation Policy Study Commission (mandated by Congress in 1976 with a final report in June 1979 assessing transportation needs through the year 2000) up through Secretary Anthony Foxx’s Beyond Traffic 2045 report in 2017.

For each of these efforts to assemble broad-based reports, the many gaps in DOT’s in-house data collection and reporting has meant that the Department must depend on the continuing work of other federal statistical agencies, particularly the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, for their extensive demographic and economic reporting. Most notable: the beginnings of journey-to-work reporting in the 1960 decennial census, now annual at the Census Bureau as the American Community Survey.

Even today, agency data programs that predate the DOT Act (particularly highways and aviation) tend to be stronger while the data programs in agencies created at the inception of the Department have been somewhat weaker (FRA, FTA and others). Creation of the Bureau of Transportation Statistics in the 1991 ISTEA law was a key moment that quickly led to the annual publication of the Transportation Statistics Annual Report (TSAR), which covers all transportation modes, passenger, and freight, safety, physical characteristics and condition of the system, energy and environmental factors, etc. However, coverage of some modes and activities is still deeper than others.

Today, the statistical weakness is particularly a challenge on the passenger side of transportation. The figure below somewhat simplistically shows that the gaps between freight and passenger reporting are at opposing ends of the geographical spectrum.

| Passenger | Freight | |

| Metro | STRONG | WEAK |

| Intercity | WEAK | STRONG |

The statistics of passenger travel are strong at the metro level, largely developed in response to Congressional legislation to better meet metropolitan commuting and other travel needs. On the freight side federal data have met economic needs of trade flows at ports and national markets while almost no focus has been on internal metropolitan freight flows. (Recent concerns about home delivery issues and the competition for curb space may engender future response in that sector.)

The intercity side of passenger flows are a challenge to address due to the massive scale and complexity of long-distance travel. Last-century surveys indicated that trips under 500 miles were almost totally dominated by the personal automobile. Air travel begins to become significant after that at greater distance levels. The other modes of rail and bus travel are relatively minor factors. The volumes and activities of international tourism and travel with the countries on our land borders are a great challenge. The airline industry and Amtrak can provide the origins and destinations of total travel volumes of passengers and seat-miles of service provided, but the trip purposes involved, and the socioeconomic characteristics of the travelers are nonexistent. The existing data does not answer the “why” of travel. The intercity bus industry including charter buses and tour bus activities serves far more riders than Amtrak, but has even weaker data on origins and destinations, trip purposes, and user characteristics.

While the format and usefulness of the TSAR is very good given the modal data limitations, the same cannot be said for the other centralized data document that DOT is supposed to release on a regular basis, the Status of the Nation’s Highways, Bridges, and Transit Conditions and Performance reports, the Highway side dating back to 1968. Mandated by Congress, the reports were not available during the entire COVID period to guide Congressional infrastructure investment legislation. The most recent, the so-called 25th edition, (the year of publication is no longer reported), is largely based on 2018 pre COVID data.

The C&P reports were commissioned by Congress to “to provide decision makers with an objective appraisal of the physical conditions, operational performance, and financing mechanisms of highways, bridges, and transit systems based on both their current state and their projected future state.” In their banner years the reports guided Congress in extensive hearings on the state of highway and transit infrastructure condition, service usage, current system capacity and service needs. In recent years the reports became so voluminous, and arrived so late, that they likely discouraged usage. The scope of the report, and the resources devoted to its production, need to be reassessed.

Looking ahead

Future considerations for the state of transportation statistical systems are challenged by funding gaps, staff skills lost in the current period (notably newly hired young graduate students lost) and most of all the lack of Congressional concern for better information to guide legislation. One area of particular challenge is that the BTS – which would be the centerpiece to any progress on improving data and information – is the smallest statistical agency in the federal Government, and one whose funding has actually shrunk since its founding. (FY 1998 budget: $31 million. FY 2026 budget: $27 million.) BTS funding needs to be broadened beyond its sole funding source – the Highway Account of the Highway Trust Fund (although attractive right now because the BTS was still working during the government shutdown). But in the future, additional direct funding from Congress via the Office of the Secretary is needed to broaden BTS’s capacity. Sadly it must be recognized in the past that the BTS lost funding to other elements of the OST.

There are strengths and weaknesses for a statistical agency’s being close to the policy leadership. Guidance to that leadership and exposure to their needs is key to program effectiveness, but being too close to the policy flame can lead to being severely singed in political battles. Broadened funding for BTS from the other modes – perhaps designed as joint efforts would be a very effective tool. Outside the Department transportation industries and research centers like AASHTO and TRB can be crucial in supporting and guiding needs assessments and response.

BTS has provided immense benefits but the gaps are still massive. Addressing BTS capacity is no less serious than funding gaps and requires examining the extent of staff and skills gaps in BTS and in the other statistical elements of the modal Administrations.

At this time there is also reason for hope. Within the Department itself, there is a sense of real interest in basing investment and regulatory decisions on the best data available and improving information-based decision making. A national survey and the development of administrative substitutes for surveying will remain a great challenge. However, a better-supported BTS and modal data programs could support better decisions, especially by expanding data collection in the area of passenger travel, particularly in the intercity/international realm.

This author cannot resist this closing story. The first Transportation Secretary, Alan S. Boyd, was advised by his staff to stop spending big dollars on long term data collection efforts because he would never even see or use the resulting products. Better, they said, to save money for his own program spending: “this stuff will take three years. It’s just a gift to your successor – forget it!” The Secretary answered: “Then we’d better get started, shouldn’t we!”

Alan Pisarski is a prominent transportation consultant. He worked in a senior role at the various USDOT data collection and analysis programs from 1969-1977 and then on the staff of the National Transportation Policy Study Commission. He is the author of the groundbreaking Commuting in America series of studies (I, II, and III) originally published through the Eno Center. He also compiled “USDOT at 50: The Early Years,” a collection of historical vignettes from USDOT staffers present in the 1967-1977 era.

The views expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Eno Center for Transportation.