August 31, 2016

House Railroad Subcommittee chairman Jeff Denham (R-CA) decided to break up his long summer recess by holding a field hearing of his subcommittee this week in San Francisco to get a status check on the California high-speed rail project.

Denham and five other legislators turned up for the hearing (which is six times as many legislators as attended the other transportation-related summer field hearing). Denham and Rep. Doug LaMalfa (R-CA) have long been critical of the project; Reps. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA) and Jared Huffman (D-CA) are longtime supporters, and Reps. Mike Capuano (D-MA) and Blake Farenthold (R-TX) fell somewhere in the middle.

- Federal Railroad Administrator Sarah Feinberg (testimony here).

- California High-Speed Rail Authority board chairman Dan Richard (testimony here).

- Caltrain CEO Jim Hartnett (testimony here). (Caltrain is a Bay area commuter rail system.)

- Stuart Flashman, attorney for the most persistent opponents of the project (testimony here).

- California Building & Construction Trades Council president Robbie Hunter (testimony here).

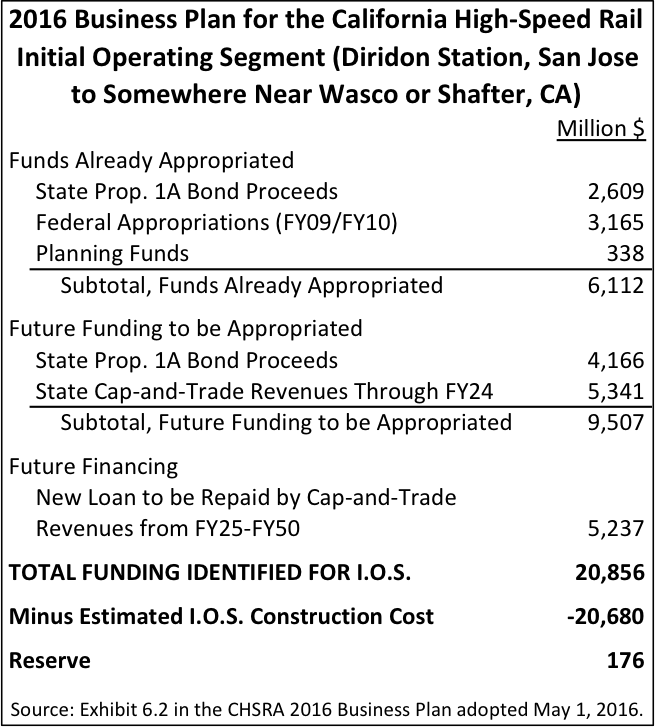

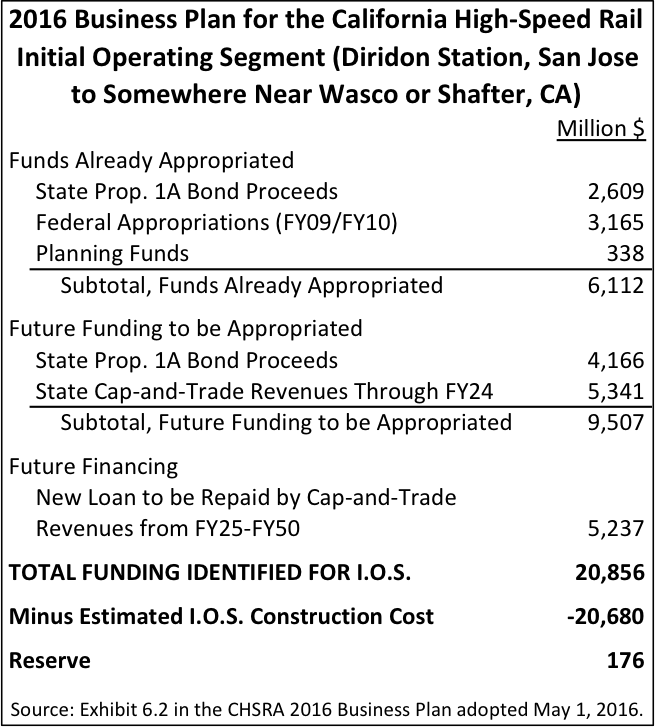

Background. The California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) did a huge about-face when it released its draft 2016 business plan in February of this year and then adopted a final plan in May. Instead of building the initial operating segment (IOS) from just north of Fresno to the San Fernando Valley at a cost of $31.2 billion, which was the earlier plan, the new business plan called for an IOS running from San Jose’s Diridon Station to an unspecified spot north of Bakersfield at a cost of $20.7 billion.

(The new business plan says that the southern terminus of the IOS can either be the station in Wasco, 24 miles northwest of Bakersfield, or else they can build an interim station in an almond orchard near Shafter, which is about 6 miles closer to Bakersfield. But $20.7 billion is not enough to get all the way into Bakersfield, nor is it enough to get to San Francisco (passengers would have to switch to Caltrain in San Jose to get to the City by the Bay). That would require another $2.9 billion in total.)

The problem with the earlier $31.2 billion IOS plan was that CHSRA only had guaranteed access to $10.2 billion ($3.3 billion in federal funds from 2009 and 2010 and $6.9 billion from Proposition 1A bond proceeds) and no solid prospects for raising the other $20.9 billion. The new, $20.7 billion IOS only needs $10.6 billion more than CHSRA already has on-hand, and they propose to get half of it from annual appropriations of state cap-and-trade emissions auction receipts from fiscal years 2016-2024 and the other half from a loan (presumably from the federal RRIF or TIFIA programs) that will be repaid with appropriations of cap-and-trade revenue from FY 2025-2050.

But even though the legislature has gone along with Governor Jerry Brown’s (D) requests so far to provide 25 percent of cap-and-trade auction proceeds to CHSRA, the auction system recently collapsed (only 10 percent of available carbon allowances were sold in the May auctions and 34 percent of the available allowances were sold in the August auctions, netting CHSRA 25 percent of just $18 million), and further action by the legislature and courts is necessary to extend the program. An analysis in Capitol Weekly this week concluded: “Until the legal foundation for the program is solidified, auctions are likely to be unstable and undersubscribed on average, resulting in a surplus of unsold allowances…”

Hearing. After all the opening statements, chairman Denham started the questioning by focusing on the need to spend the expiring money from the 2009 stimulus law. $2.5 billion of the federal appropriations to date were from the ARRA stimulus law, and even though the money has been legally obligated for the project, any money not actually spent (outlaid) by September 30, 2017 will evaporate in a puff of smoke, leaving CHSRA to scramble and find money elsewhere to pay off obligations.

Richard said that burn rates were now on track and that he had “no doubt” that the 9-30-2017 deadline would be met. Denham then asked both Richard and Feinberg to make a public commitment that they would not request an extension of the deadline, and they both did so. Denham later said that his main concern was that most or all of the cap-and-trade money would never materialize and that this would leave only a rump system running from Madera (25 miles of Fresno) to Wasco for decades while California waited to “steal money” from the Northeast Corridor or elsewhere.

LaMalfa repeatedly hit Richard over how the current plans for the project differ from the promises made to California voters in 2008 when the state voted narrowly in favor of Proposition 1A. Richard’s response was that he was not there in 2008 but that a system consistent with the requirements in Prop 1A can still be built.

When responding to Rep. Huffman, Richard said that Prop 1A made it clear that the $9 billion in bonds authorized by that referendum were only a down payment on the entire system. Huffman also pointed out that the Golden Gate Bridge was an incredibly controversial and lawsuit-prone project in its day, but today the completed bridge is one of the wonders of the modern world. (Ed. Note: The Golden Gate Bridge was built without any federal or state funding – it was entirely a local bond initiative repaid by tolls. Probably the wrong example to cite for a completely intrastate project seeking massive federal appropriations in the future.)

Flashman (the attorney for the plaintiffs in the main lawsuit against the project) seemed to be at the hearing as a factual backstop for Denham and LaMalfa’s criticisms of the project. His testimony pointed out that while the state can appropriate money from Prop 1A for the project, the money cannot actually be spent on construction until CHSRA produces a final funding plan that includes a certification by an independent financial consultant that the rail service provided on the initial corridor or segment will not require an operating subsidy. This has not yet happened, and any such certification that HSR from San Jose to an orchard near Bakersfield will not require operating subsidies will be a very interesting read.

Richard argued that the California legislature passed a new climate policy the week before setting even lower emissions targets by 2030 that would put the cap-and-trade auction system back on track and restore stability to that promised revenue stream. (Stability of a revenue stream is the key to getting a $5 billion TIFIA or RRIF loan.) But the aforementioned analysis in Capitol Weekly from a California energy market expert concluded that “The imminent signing of new 2030 legislation is a tremendous step forward. Unfortunately, allowance auctions will remain in the new normal of low allowance demand until legal questions around post-2020 allowance auctions are truly vanquished — all of the allowances made available at auction will simply not sell.”

Lofgren defended the project and noted, correctly, that all large new systems are built in pieces.

(Ed. Note: What no one, in this or any other hearing on the subject, has really focused on is the real fundamental question. It has long seemed to ETW that when building a new fixed-guideway system (as opposed to an upgrade to an existing system), it is a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad idea for the federal government to fund construction of anything less than a fully operable segment which has its local funding match and its environmental clearances nailed down in advance. This is why the Federal Transit Administration’s New Starts program is such a success – only vetted projects for minimum operable segments with completed funding plans can get to the stage where FTA signs a full funding grant agreement (FFGA) and lets construction begin. Instead, FRA chose in 2010-2011 to commit almost $3.5 billion to a “initial construction segment” (ICS) between Bakersfield and Merced, the grant agreement for which acknowledged that it lacked the money to buy high-speed trains to operate on that line, so it could not be considered an operable segment.)

Lofgren did ask Richard about a worst-case scenario – in case cap-and-trade fails and the ICS (Wasco to Merced track upgrades but no high-speed trains to run on it) is all there is, what then? Richard responded that he would not want his name or Governor Brown’s name attached to a piece of track that does not connect to the rest of the state, but that the $6 billion for the ICS in the Central Valley would eliminate 60 or so existing grade crossings on the existing rail lines and would therefore provide a safety benefit, as well as increasing freight efficiency from getting passenger trains off the freight rail lines.

(Ed. Note: $6 billion for grade crossings? There has long been a dedicated federal revenue stream for grade crossing upgrades nationwide, out of the Highway Trust Fund, which was capped at $220 million per year for many years (though increased by the FAST Act and recent appropriations action). $6 billion is equal to 27 years worth of a $220 million per year section 130 grade crossing program.)

Subcommittee ranking minority member Capuano wished Richard luck on the project but noted that, when it comes to the future federal dollars that CHSRA hopes will be forthcoming for the project, “the pie is shrinking and the demand is growing.”

Archived video of the hearing is available here.