George H. W. Bush (1989 to 1993): Shining a Spotlight on Transportation

This article is a part of our series From Lighthouses to Electric Chargers: A Presidential Series on Transportation Innovations

World history changed during the presidency of George H. W. Bush. His diplomacy was a major factor in the reunification of Germany; Saddam Hussain’s army was soundly defeated by coalition forces led by the United States; and the Soviet Union was formally dissolved.

major factor in the reunification of Germany; Saddam Hussain’s army was soundly defeated by coalition forces led by the United States; and the Soviet Union was formally dissolved.

And yet, despite its attention to these pivotal global developments, no administration since Eisenhower’s placed transportation as prominently on the national policy agenda as that of America’s 41st president. He served only one term, but his policies and the changes they wrought were transformative across much of the transportation sector. His administration also had to respond to more than its share of domestic emergencies – air disasters, union strikes, hurricanes, an oil spill, and an earthquake. President Bush’s two Secretaries of Transportation, Samuel K. Skinner and Andrew H. Card, Jr., repeatedly found themselves in the center of the action.

President Bush’s first Secretary, Sam Skinner, a gifted lawyer and executive from Chicago, was a former U.S. Attorney who had gained national attention for his successes in addressing corruption, including the prosecution of a federal judge, Otto Kerner, Jr. He had then moved to private practice and, for four years, had simultaneously served as chairman of greater Chicago’s Regional Transportation Authority, the nation’s second-largest mass-transportation district.

President Bush had announced that establishing a comprehensive national transportation policy would be a high priority. Accordingly, following his unanimous confirmation by the Senate, Secretary Skinner launched a DOT-wide project to formulate that new policy. He wanted it done early, so that it would guide the government’s activities throughout the Bush administration and beyond. Deputy Secretary Elaine L. Chao and Federal Highway Administrator Thomas D. Larson were put in charge.

For those of us at DOT at the time, the “NTP,” as the national transportation policy was called, became an all-encompassing undertaking involving every one of the many modal administrations within the vast and diverse agency. It was far more than a writing exercise. Officials from every corner of the department were deployed to communities throughout the country, conducting more than 100 hearings, attending town hall meetings, appearing on radio talk shows, and meeting with trade associations, unions, and user groups of every kind.

The very public character of the process had two important benefits. First, it exposed DOT to the concerns of transportation users and providers from all parts of the country. Second, it made attention to America’s transportation system a conspicuous imperative. For the first time, “infrastructure” became a household word. The importance of transitioning to a more contemporary and responsive approach to the country’s transportation requirements was understood and reinforced by a far more knowledgeable public. Legislators noticed.

Not surprisingly, it also had a third important effect, albeit one known only within DOT itself. I had worked at the department as a career employee in previous administrations and had never seen a higher level of staff morale and enthusiasm than during the NTP project. Nothing makes public servants happier than knowing their work is seen as important by the public they serve. That was never more true than during the NTP project.

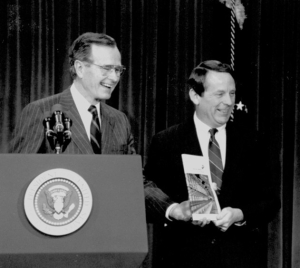

The product of all this activity was a detailed and forward-looking report entitled Moving America: New Directions, New Opportunities. On March 8, 1990, President Bush joined Secretary Skinner for its public release at an event in the Old Executive Office Building.

Pres. Bush and Secretary Skinner releasing the report on March 8, 1990. A nine-minute video of the event is available at CSPAN.

The President had contributed a signed introduction that included some stirring words:

History must record that we took charge of our destiny and left a new generation with a better environment, a higher quality of life, and greater opportunities. To achieve this goal, transportation and transportation policy can be—must be—a vital agent for change. We have already reaped substantial benefits from regulatory reform and economic deregulation in transportation, and the Nation must build on that success. In the coming years, the transportation system must be an integral part of our investment in America’s future.

It was a profoundly important expression of commitment at the highest level to the importance of transportation both to the national economy and to the quality of life. Nobody missed it.

Secretary Skinner’s own introduction to “Moving America” noted that this was a pivotal moment:

The next decade can be a watershed in the history of transportation in America. On the threshold of a new century, we have an opportunity to address the challenges of a changing society, a changing economy, new technology, and new roles and possibilities for all the members of the transportation community. There is significant potential for increased private sector involvement in transportation, including owning and operating toll roads and transit, and financing a broad range of projects through innovative corporate and joint public-private initiatives.

He noted that Congress would shortly be required to pass legislation renewing the authorization of the federal aviation, mass transit, highway, and highway safety programs. “Those reauthorizations,” Skinner wrote, “provide a chance to renew the transportation partnership, recognizing the increased responsibilities and capabilities of the State and local and private sector partners. The legislation must give other levels of government the flexibility, the responsibility, and the tools they need to address critical requirements in transportation.”

With the Interstate system largely completed, the NTP signaled the transition to a new era and established an ambitious agenda for the Bush presidency. While calling for the expansion and improvement of America’s transportation system, it included among its other principal themes the encouragement of more public-private cooperation as well as user fees and innovative financing; a shift of more decision-making authority and greater flexibility to states and cities; an emphasis on intermodal solutions; the elimination of anachronistic and unnecessary regulations; and more flexibility in the use of federal transportation money.

SURFACE TRANSPORTATION AND ISTEA

The principles spelled out in the NTP were key drivers behind DOT’s draft reauthorization bill for America’s surface transportation programs. Initially entitled the “Surface Transportation Assistance Act,” the bill was announced by President Bush at a White House press conference on February 13, 1991, not quite a year after the release of the NTP.

Over the course of ten months of Congressional deliberations, as spelled out in Richard Weingroff’s richly detailed narrative, “Creating a Landmark,” STAA became ISTEA – the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991. The legislation was heavily based on the administration’s proposed bill and delivered on a majority of its priorities.

President Bush signed the bill on December 18, 1991, at a highway construction site in Texas not far from Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. ISTEA, he said during the ceremony, was “the most important transportation bill since President Eisenhower started the Interstate System 35 years ago.”

President Bush signs ISTEA in 1991. From left, construction worker Arnold Martinez, Rep. Bud Shuster, President Bush, Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (in hat), Rep. John Paul Hammerschmidt, Rep. Robert Roe, and Rep. Norman Mineta ( a future U.S. DOT secretary). Source: US DOT.

He was right. According to the legislation that had established DOT a quarter-century earlier, the department was expected to “make easier the development and improvement of coordinated transportation service….” The goal of an intermodal approach to transportation planning had nevertheless remained elusive.

ISTEA, in keeping with DOT’s earlier recommendations in Moving America, represented the first serious effort to address the way federal funding had distorted transportation planning for decades. It established unprecedented flexibility in the way states and local governments could use federal funding; placed an emphasis on the maintenance and improvement of a newly designated “National Highway System”; encouraged innovative financing; identified projects of national significance and “high priority corridors”; encouraged new approaches to congestion mitigation; and presciently authorized research focused on making both highways and vehicles safer. It set the tone for all subsequent reauthorizations of DOT’s surface transportation programs.

AVIATION POLICY

The Bush administration’s impact on America’s surface transportation programs was matched by the innovations it brought to aviation.

Domestic aviation policy. Early in the administration, Secretary Skinner, aware of complaints about increasing airline concentration in the U.S. air travel market, directed his policy office to conduct an in-depth analysis of the aviation marketplace. The result was a comprehensive, peer-reviewed, nine-volume study of domestic aviation in the United States. Among its findings was that, even though the market was being served by fewer airlines as the result of airline mergers approved during the 1980s, consumers were actually benefiting from more competition than ever, measured in terms of the increased choices available to travelers flying between America’s cities. The study furnished DOT with a solid, empirical foundation upon which to base its subsequent actions and legislative activity relating to the aviation sector.

To inject even more competition into the domestic air travel market, the Bush administration strongly supported the bill that became the Aviation Safety and Capacity Expansion Act of 1990. The NTP had recommended allowing airports to collect passenger facility charges, and a provision in the bill did just that, requiring only that each such “PFC” be approved in advance by the FAA.

Secretary Skinner knew the airline industry opposed PFCs. They feared that adding a few dollars to the price of every ticket would dampen demand. He instructed me to contact a number of airline CEOs to ask for their cooperation. Together with a few colleagues, I did so. We knew it would be too much to ask for their outright support, I told the executives, but we would be grateful if they would at least refrain from actively fighting the provision. They reluctantly agreed.

The head of the Air Transport Association (later renamed “Airlines for America”) canceled testimony he had planned to provide to the House committee considering the bill. A reporter at the Washington Post received word that the phone calls had implicitly threatened punishment of any airline that continued to oppose the PFC proposal. A DOT administrative proceeding was taking place at the time in which lucrative new routes to destinations in Asia would be awarded, and the accusation was that opposition to PFCs would diminish an airline’s prospects for success.

The allegation was nonsense, but it caused serious concern at DOT. I called the reporter personally and told him he must have been badly misinformed by an excessively creative airline lobbyist. If I had threatened CEOs that an international route award might be blocked over PFCs, I said, “they would have fallen out of their chairs laughing.” That line found its way into the reporter’s story the next day. We heard nothing more about threatening international routes, and the PFC provision was included in the legislation that was sent to President Bush for signature. Thanks to the Bush administration’s courageous advocacy of PFCs and Congress’s concurrence, airports have since benefited from more than $75 billion in additional capital to support improvements and expansion.

In another important contribution to the quality of competition in the aviation market, the Bush administration increased the efficiency of operations at capacity-constrained airports – notably New York’s JFK International and LaGuardia Airports and Washington Reagan Airport – by increasing the minimum usage by airlines holding valuable runway slots from 60 percent to 80 percent.

Secretary Skinner proposed at one point to add further capacity to the system by removing the limits on runway slots at Washington Reagan and New York LaGuardia Airports. A secondary market for the buying and selling of slots already existed, and Skinner believed the market might produce better results than regulation. Donald Trump and a consortium of banks had recently purchased the Eastern Shuttle for $360 million and renamed it the Trump Shuttle. The airline served the Washington-New York- Boston corridor. Concerned about the impact of the proposal on schedule reliability, and possibly on his equity in the airline (slots were worth more with the cap than without), Trump immediately sought a meeting with Secretary Skinner. Reducing the reliability of schedules at the affected airports would quickly affect reliability throughout the system, he argued. Because the FAA had strongly objected to the proposal on similar grounds, Secretary Skinner abandoned the proposal

International aviation competition. The Bush administration’s most important contribution to competition in aviation, however, was its transition to a revolutionary Open Skies policy – a dramatic departure from the traditional, highly protectionist approach to negotiating international landing rights that had been prevalent for decades. It is difficult to overstate the implications of this change for the role international aviation plays today in the global economy.

The liberalization of international flying had begun during the Carter administration, and by the beginning of the Bush administration many air travel markets were enjoying some measure of increased competition. But many markets had remained subject to highly restrictive bilateral agreements that continued to hamper the growth of aviation and global connectivity.

Secretary Skinner had selected me to run DOT’s policy office. I had just spent four years as a deputy assistant secretary at the State Department conducting bilateral aviation negotiations and thought that it might well be possible to take liberalization to a higher level. Of course, to do that, I would have to persuade my new boss.

In October 1989 I sent Secretary Skinner a one-page memo describing the proposed policy change. I knew it would be controversial, particularly among U.S. airlines who preferred the limits on competition imposed by the traditional approach. Still, my hope was that Skinner would ask me to meet with him, explain the concept in more detail, and give him the pros and cons. Then, I hoped, he would direct me to convene an interagency committee, put more flesh on the bones of the idea, and come back to him with a recommendation. That, after all, was the way government made policy.

He did none of that. Instead, my memo was returned to me two business days later. Scrawled in the margin: “Go for it. S.” It was an unforgettable moment, and it changed everything.

Understanding the negative impact on American communities of the artificial limitations placed on flying by the traditional approach, Secretary Skinner had authorized the development of a novel departure: the airlines of any country willing to desist from the regulation of entry, routes, capacity, and pricing would be given unfettered access to all American cities, and to all destinations beyond the U.S. In other words, the rules governing international aviation would at long last begin to look like the rules governing most other sectors of international trade. We went to work developing a strategy.

At the end of 1991, President Bush asked Secretary Skinner to move from DOT to the White House as his Chief of Staff. He was succeeded in February 1992 by Andrew H. Card, Jr., who had been serving until then as President Bush’s Deputy Chief of Staff.

In the course of his briefings on all that was going on at DOT, Secretary Card was told of the international aviation policy work launched earlier. We warned him that U.S. airlines were quite happy with the status quo and its limits on foreign carrier access to the domestic market. The airlines had vehemently opposed the Carter administration’s modest efforts to liberalize international flying 15 years earlier. Proposing now to remove all of the restrictions might well trigger a firestorm of criticism. During his long career in politics, however – eight years in the Massachusetts House of Representatives and then more years as a senior White House official in both the Reagan and Bush administrations – Secretary Card had acquired a well-developed sense of when public policy needed changing, even in the face of industry opposition. Within just a few weeks of his arrival at DOT, therefore, Secretary Card authorized the formal proposal of a new Open Skies policy for the United States. In August 1992, following the required notice-and-comment period, he directed the staff to issue an order finalizing the policy.

The Netherlands was the first country to express interest in signing an Open Skies agreement with the United States. This was no surprise; Dutch aviation policy was among the world’s most liberal. Ironically, however, that made the Netherlands an unfortunate candidate as our first Open Skies partner. Because U.S. carriers were already allowed to fly to and through Amsterdam without any regulatory constraints, an Open Skies agreement with the Netherlands would grant KLM vastly increased access to the United States and beyond while giving U.S. airlines absolutely nothing new. A more lop-sided agreement would be hard to imagine.

Secretary Card understood all this but, like Secretary Skinner before him, he knew the new policy represented a breakthrough that could bring enormous benefit to U.S. communities and their citizens. The sooner its value was demonstrated, therefore, the better. He green-lighted the negotiations and, two months later, he and his Dutch counterpart, Transport Minister Hanja Maij-Weggen, signed the world’s first Open Skies agreement. To everyone’s relief, the industry’s criticism was relatively muted.

Based on the fully open market for flights that now existed between the two countries – competitors could enter at will – DOT approved and granted antitrust immunity to a novel alliance proposed by Northwest Airlines and KLM Royal Dutch Airlines. They wanted to operate, they said, as though they were a single carrier. The approval and immunity conferred on Northwest and KLM appealed to other airlines. Within a relatively short time, other cross-border alliances were applying for approval and immunity. Because DOT had made an Open Skies agreement a prerequisite to the approval and immunity of such alliances, the U.S. began to find a lot of aspiring Open Skies partners.

The Open Skies policy has been embraced by every subsequent administration, Democrat and Republican. The United States today has more than 130 Open Skies agreements with trading partners everywhere, expanding the number of convenient itineraries available to U.S. and foreign travelers alike, increasing the flow of tourism and trade to U.S. cities, and lowering average airfares by nearly a third. Open Skies has become close to a default policy globally, representing nothing less than a revolution in the contribution of international air services to national economies everywhere.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

From the very beginning, the Bush administration confronted an extraordinary number of emergencies. President Bush repeatedly looked to DOT’s leadership to provide or coordinate the government’s response to this unprecedented parade of challenges. In just about every case, public policy improved as a result of lessons learned, often accompanied by new legislation and/or administrative changes.

Pan Am 103. Less than a month before President Bush’s inauguration, on December 21, 1988, Pan American’s Flight 103 crashed at Lockerbie, Scotland, killing 243 passengers, 16 crew members, and 11 people on the ground. A bomb had been placed in the luggage hold by a Libyan terrorist. After meeting with the families of the victims, President Bush established the President’s Commission on Aviation Security and Terrorism to investigate the circumstances surrounding the bombing and evaluate U.S. aviation policies and practices regarding terrorist threats. While the Commission formulated its recommendations, Secretary Skinner and members of his team visited a number of foreign capitals to establish cooperation on raising the level of aviation security throughout the world.

Based on the Commission’s recommendations, Secretary Skinner created a new Office of Intelligence and Security as part of the immediate office of the Secretary, thereby ensuring more focused attention on security in all modes of transportation. Also in response to the Commission, Congress passed the Aviation Security Improvement Act of 1990. The legislation contained requirements to improve passenger screening, enhance coordination between intelligence agencies and aviation authorities, and improve aviation security in other ways.

Eastern strike. On March 4, 1989, the International Association of Machinists went on strike against Eastern Airlines due to long-festering differences over working conditions and wages. Members of the Air Line Pilots Association walked off the job in support. The strike lasted for more than seven months. Secretary Skinner mediated between the parties and worked to ensure that the dispute did not diminish the safety of Eastern’s operations. The economic impact on Eastern was severe, however, and the airline was forced to close its doors for good by 1991.

Exxon Valdez. On March 24, 1989, the oil tanker Exxon Valdez struck a reef near the Alaskan coast spilling nearly 11 million gallons of crude oil into Prince William Sound. It was the second worst oil spill in U.S. history. President Bush immediately dispatched Secretary Skinner to Alaska, making him responsible for the coordination of all federal agency efforts in response to the spill. He and EPA Administrator William K. Reilly co-authored a report to the President spelling out the damage wreaked by the spill, detailing deficiencies in the government’s preparedness, and making recommendations for dealing with such catastrophes in the future. The report’s recommendations were promptly taken up by Congress. The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 was passed shortly thereafter with strong administration support. Among other things, the act established new levels of financial responsibility for oil tanker operators, to be enforced by the Unites States Coast Guard, as well as a requirement that they maintain effective oil spill response plans.

Sioux City air crash. On July 19, 1989, while en route from Denver to Chicago, United Airlines Flight 232 lost its tail-mounted engine as well as all hydraulic systems. Remarkably, the crew was able to guide the airplane toward Sioux Gateway Airport in Iowa, steering the aircraft by using its two remaining engines. The aircraft still crashed upon landing, but thanks to the superb performance of the crew, 184 of the 296 people on board survived. Working closely with the National Transportation Safety Board, DOT and the FAA drew important lessons from the accident and developed a number of important aviation safety improvements as a result.

Hurricane Hugo. Two months later, on September 22, 1989, Hurricane Hugo, a Category 5 storm, made landfall near Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina. It caused some $11 billion in damage throughout the Caribbean and the southeastern United States and left 67 dead. Secretary Skinner served once again as the coordinator of the federal response, accelerating the restoration of roads, bridges and port facilities damaged by the storm in order to support the delivery of supplies and facilitating recovery.

Loma Prieta earthquake. Less than a month after that, on October 17, 1989, a 6.9 magnitude earthquake struck the Central Coast of California, centered near Loma Prieta Peak in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Portions of the Nimitz Freeway in Oakland collapsed as well as a sections of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. More than 12,000 people were displaced, 3,700 were injured, and 63 died. Yet again, President Bush turned to DOT and Secretary Skinner to oversee the federal response and to find ways to hasten the repair of the damaged transportation infrastructure.

Rail strike. On April 17, 1991, after failing to achieve agreements on wages, benefits, and working conditions, eight railroad unions announced a nationwide rail strike. Thanks to swift action by Congress and President Bush, the strike lasted only one day. Congress quickly passed legislation sending the strikers back to work, and President Bush signed the bill into law on April 18. Secretary Skinner had testified before Congress about the potential economic consequences of a prolonged strike and emphasized the urgency of resolving the dispute.

Hurricane Andrew. In late August 1992, Hurricane Andrew, one of the strongest ever to hit the United States, devastated parts of South Florida and Louisiana. Once more, President Bush turned to DOT – this time to Secretary Andrew Card – for leadership in coordinating the federal response. Secretary Card was widely recognized for his success in streamlining the provision of federal support to state and local governments.

CONCLUSION

“History must record,” President Bush wrote in his preface to Moving America in early 1990, “that we took charge of our destiny and left a new generation with a better environment, a higher quality of life, and greater opportunities.” He had every reason, as he left office three years later, to be satisfied with his delivery on that promise.

The improvements in transportation policy and legislation that emerged during his term were wholly attributable to his wisdom in selecting two extraordinary leaders for DOT – two Secretaries of Transportation in whom he obviously had unbounded confidence and whom he repeatedly called upon in the most difficult circumstances. In turn, Secretaries Skinner and Card both quickly demonstrated their own unbounded confidence in DOT’s professional staff, a level of respect and even affection that made the administration of President George H. W. Bush one that is fondly remembered by everyone fortunate enough to have worked at DOT during that time, despite the extraordinary challenges it faced on so many fronts.. The vision and courage consistently demonstrated by DOT’s leaders in embracing the right answers represented public service at its best.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Jeff Shane launched his career at US DOT as a trial attorney in 1968, the first of five tours of duty at the department spread over 40 years. He was assistant secretary for policy and international affairs during the George H. W. Bush administration and was later appointed DOT’s first under secretary for policy by President George W. Bush. He was also deputy assistant secretary for transportation affairs at the State Department where he served as chief US aviation negotiator. He practiced law in Washington for many years and was general counsel at the International Air Transport Association.