Federal Funding for Intercity Rail – A Primer

Introduction

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 (IIJA) was the largest investment in transportation and infrastructure since the Federal Aid Highway Act which established the interstate highway system. Within the IIJA was a massive boost of long-term, dedicated funding for rail (including freight and passenger rail) in the United States over its five-year authorization period. As the time of IIJA draws to a close, members of Congress and the transportation industry are beginning to discuss the transportation priorities in the upcoming 2026 surface transportation reauthorization and the future of rail funding will be a critical question. Surface transportation reauthorization is an opportunity to provide significant federal funding for transportation and infrastructure investments. For rail, the upcoming surface reauthorization will determine whether rail funding receives guaranteed federal funding over time.

Government investment in rail is not new. Major land grants and loans provided by the government supported the development of the railroad network in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The federal government heavily regulated railroads, setting railroad rates and requiring railroads to run passenger service regardless of ridership or profit. In 1970, the federal government created the national passenger carrier Amtrak and historically funded Amtrak through annual operating and capital grants.

Recent investments in rail, particularly passenger rail, starting with the 2015 Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act and then the IIJA set the stage for greater opportunities to expand government support for rail. This rail funding piece has three parts: Part 1 looks at the history of rail funding in surface reauthorization bills including the IIJA, Part 2 includes information on various funding tools, and the conclusion discusses the considerations for rail funding in the upcoming surface reauthorization.

Part 1: History of Federal Rail Funding Policy

Federal rail policy pre-2008

Early surface reauthorizations in the modern era did include some rail or rail-adjacent funding. The Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA) of 1991 included $4.9 billion in appropriations for fixed-guideway modes like exclusive busways and rail transit under the Fixed-Guideway Modernization program. Other rail infrastructure projects like the Danville Rail Passenger station in Virginia, the Greensburg rail station in Pennsylvania, and the Lafayette Depot in Indiana received funding from ISTEA.

In 1998, the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21) created the Railroad Rehabilitation & Improvement Financing (RRIF) program. Under this program USDOT is authorized to provide direct loans and loan guarantees up to $35 billion to finance the development of railroad infrastructure. Examples of eligible activities include developing intermodal facilities, improving railyards and shops, installing positive train control systems, or financing transit-oriented development.

While these early reauthorizations incrementally expanded federal investment in transportation and infrastructure, rail was not the centerpiece of funding. Compared to highway investment, funding for rail in these reauthorizations remained modest, and focused on fixed-guideway transit, rail-infrastructure, and some intermodal.

Rail Funding post 2008

In 2008, passenger rail policy advanced significantly outside the context of a comprehensive surface transportation reauthorization. The Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act (PRIIA) reauthorized Amtrak and called on USDOT, the FRA, and other stakeholders to improve service, operations, and facilities related to passenger rail. The Act authorized several intercity passenger rail programs including the Intercity Passenger Rail Service Corridor Capital Assistance program, High Speed Rail Corridor Development program, and a Congestion Relief program.

In 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) included an $8 billion emergency appropriation in capital assistance for high-speed rail corridors and intercity passenger rail service. ARRA required the USDOT Secretary to issue a plan on how to use the funds for high speed and intercity passenger rail. The law also required the FRA to issue guidance on grant terms and procedures, which would help address the high-speed rail, capital assistance program, and congestion relief programs established in PRIIA.

The FAST Act, passed in 2015, was the first reauthorization to specifically include an authorization of passenger rail funding. The act also established three new discretionary grant programs that provided funding to states, local governments, short-line railroads, and Amtrak. These were the Consolidated Rail Infrastructure & Safety Improvements (CRISI), Federal State Partnership for State of Good Repair, and Restoration & Enhancements grant programs. The FAST Act created a $10.3 billion authorization of appropriations for Amtrak and the discretionary grant programs.

For Amtrak, the act reorganized its funding structure. The law split authorized funding between a National Network account and a Northeast Corridor account. Prior to the FAST Act, Amtrak received annual funding through two grants: one for operations and one for capital projects.

PRIIA, ARRA, and FAST reflected a change in the FRA’s relationship with passenger rail. Prior to these pieces of legislation, the function of the FRA was mainly as a regulatory agency, enforcing rail safety regulations. However, the FRA took on the role of a grant provider under PRIIA and ARRA, thus expanding the role of the FRA beyond regulation enforcement. Providing federal assistance through grant programs positioned the FRA to promote the improvement and expansion of the rail network.

The FAST Act laid the groundwork for federal investment in rail with the creation of new rail-specific grant programs. It changed some of the framework of funding by splitting the Amtrak funding between the Northeast Corridor and the National Network, which indicates a difference in their operational and capital needs.

Importantly though, with the exception of the ARRA funding, all of this was still subject to appropriation. With only an authorization of rail funding, Amtrak still had to wait for yearly Congressional appropriations (the money actually available for Amtrak to spend on projects). If Amtrak is relying on yearly appropriations, they do not have the certainty that they will have money available to complete multi-year, multi-billion-dollar projects. Therefore, Amtrak cannot provide confidence to partners that it can complete a major project. Although most rail programs received appropriations amounts that slightly exceeded the authorized levels, the level of funding was never certain beyond the current year, so Amtrak had to operate under some level of uncertainty that undermines long-term planning.

Rail Funding in the IIJA

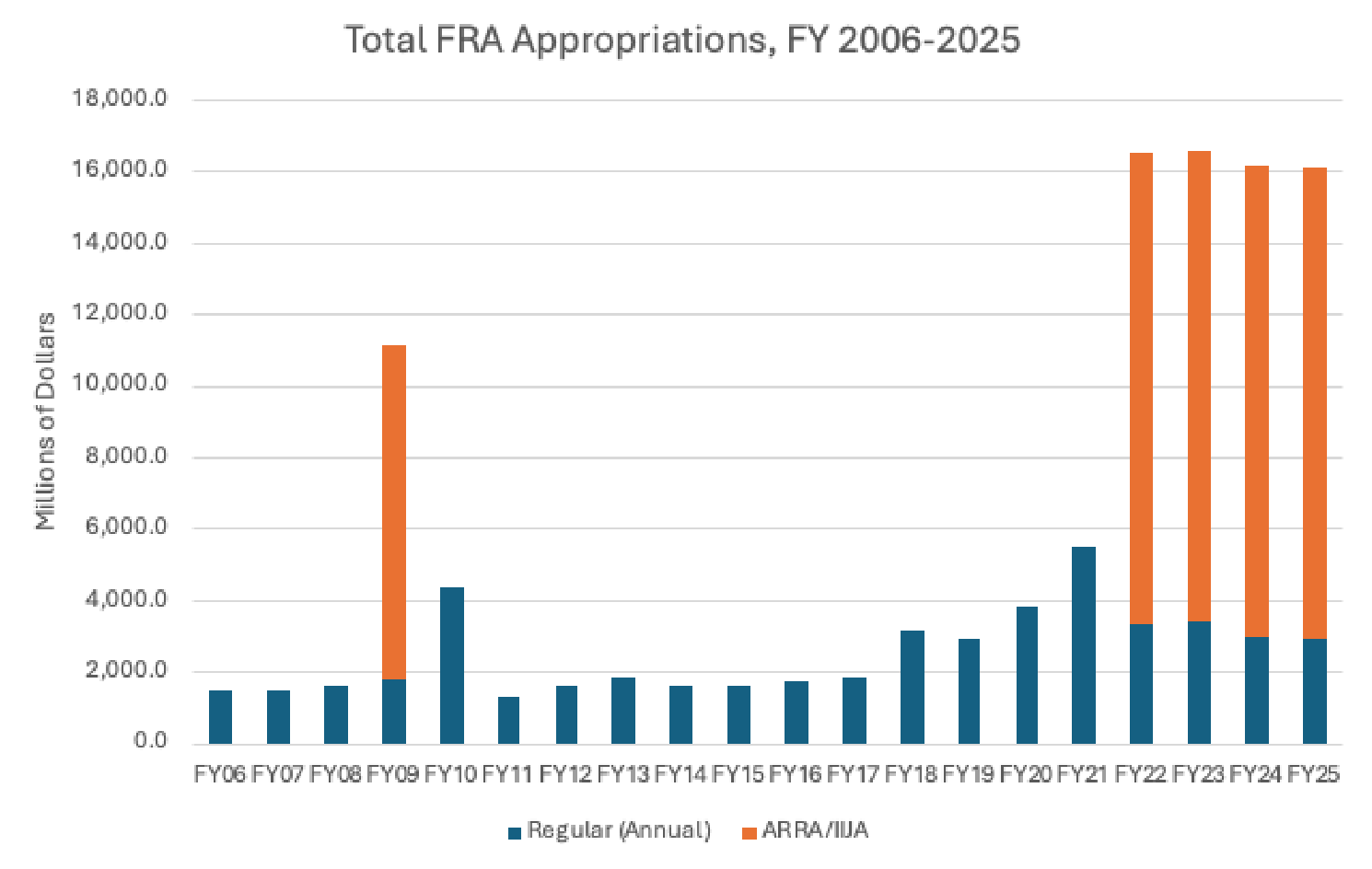

To get a sense of the IIJA’s impact on rail funding, Figure 1 shows the total FRA appropriations over time. The ARRA and IIJA provided significant, one-time increases in appropriations for the FRA.

Figure 1. Total FRA Appropriations, FY2006-FY2025

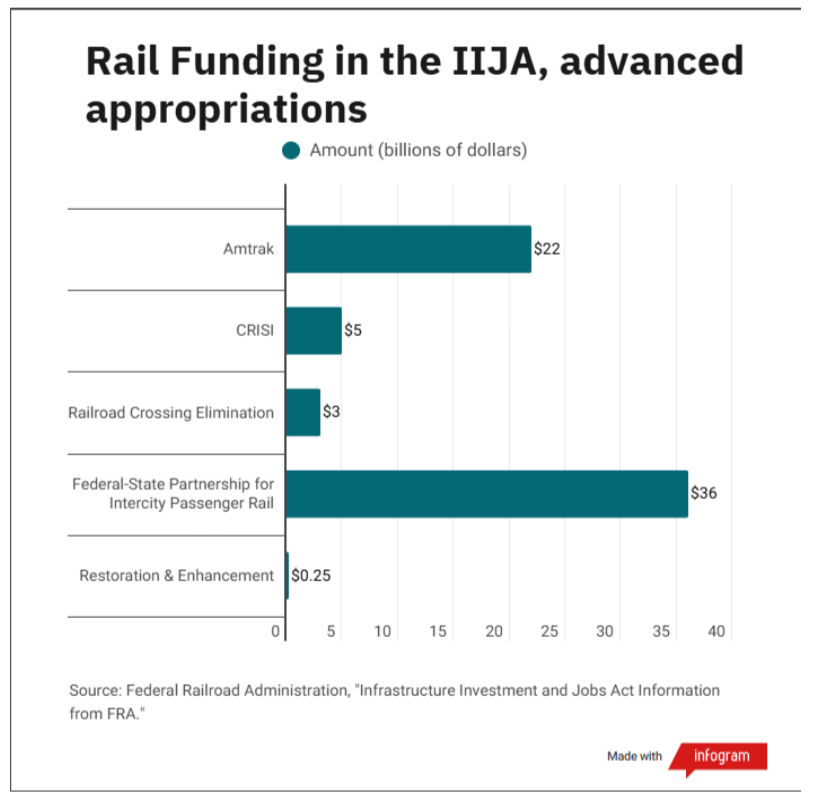

For rail, the IIJA envisioned $102 billion in total rail funding: $66 billion in advanced appropriations and $36 billion in additional annual appropriations, subject to availability. Figure 2 below shows the breakdown of funding from the advanced appropriations.

Figure 2. Rail Funding Breakdown in the IIJA

*The FAST Act’s Federal-State Partnership for State of Good Repair program was renamed to Federal-State Partnership for Intercity Passenger Rail by the IIJA.

Both the FAST and IIJA collectively moved U.S. rail policy from marginal funding within surface programs to dedicated federal investment in passenger and freight rail. The IIJA continued and scaled up the approach from the FAST Act, by authorizing multiple rail funding programs, but the legislation also dramatically changed the nature of federal investments in rail by providing $66 billion in advanced appropriations.

Simply authorizing did not guarantee that Amtrak had money to spend on projects. IIJA changed that with the advanced appropriations, where there was a set amount of money available for Amtrak over 5 years, which meant Amtrak did not have to wait for Congress every year to give them money to spend on projects. The advanced appropriations provided Amtrak with the necessary funding for major capital projects and important maintenance that the railroad would otherwise not be able to do if it constantly relied on yearly appropriations.

Most importantly, providing certainty of future funding levels gave Amtrak the ability and confidence to plan a multi-year capital program. Through its new ability to plan with certainty, Amtrak has advanced a host of major investments including major bridge and tunnel projects along the Northeast Corridor, plans for a modern fleet of locomotives and trainsets, station improvements, and investments in Chicago’s rail infrastructure, the major hub of Amtrak’s National Network. Amtrak established a new Capital Delivery department in 2022, which is responsible for delivering Amtrak’s infrastructure projects, including the planning/design, construction, and operations.

The “advanced” part of advanced appropriations is the critical difference with IIJA. Instead of waiting every year for appropriations, Amtrak had money appropriated at the outset, which gave them the ability to plan for larger projects. This was a critical step for rail funding because it made guaranteed rail funding over time a reality.

However, the IIJA’s advance appropriations encompasses many non-rail programs as well, and the appropriations section was not included solely for the purpose of creating a de facto passenger rail trust fund. Therefore, the continuation of the rail provisions of the advance appropriations section is by no means guaranteed in a future reauthorization. Moving away from guaranteed funding will halt the progress and commitments already made in rail investment. A field with crops already planted in the ground that is not properly maintained continuously will not succeed in producing a healthy yield. Thus, the farmer will not enjoy the fruits of their labor. Already Amtrak is confronting long-term uncertainty again as the expiration of IIJA in 2026 approaches, which is beginning to undermine their ability to manage their long-term capital construction portfolio.

Part 2: Utilization of Rail Funding and Financing Tools

Federal law has created a variety of funding and financing tools designed to support rail projects. Alongside existing funding mechanisms, there is a proposed funding tool in the form of a passenger rail trust fund.

Loan Programs

As discussed above, since 1998, the USDOT provides direct loans and loan guarantees through the RRIF program for projects to develop railroad infrastructure. In 2024, USDOT put in a rule that changed the interest rate setting for long term RRIF and Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) loans. The rule also made changes to TIFIA. Projects must meet only the requirements outlined in the Federal Code of Regulations and do not need to be consistent with a state transportation plan. The changes to RRIF and TIFIA expand the scope of projects that are eligible for loans. Projects that will generate enough revenue to pay back a loan are better suited for RRIF. These can include projects that involve Class I railroads or established public transit authorities, as they could be in a strong position to repay.

Private Activity Bonds

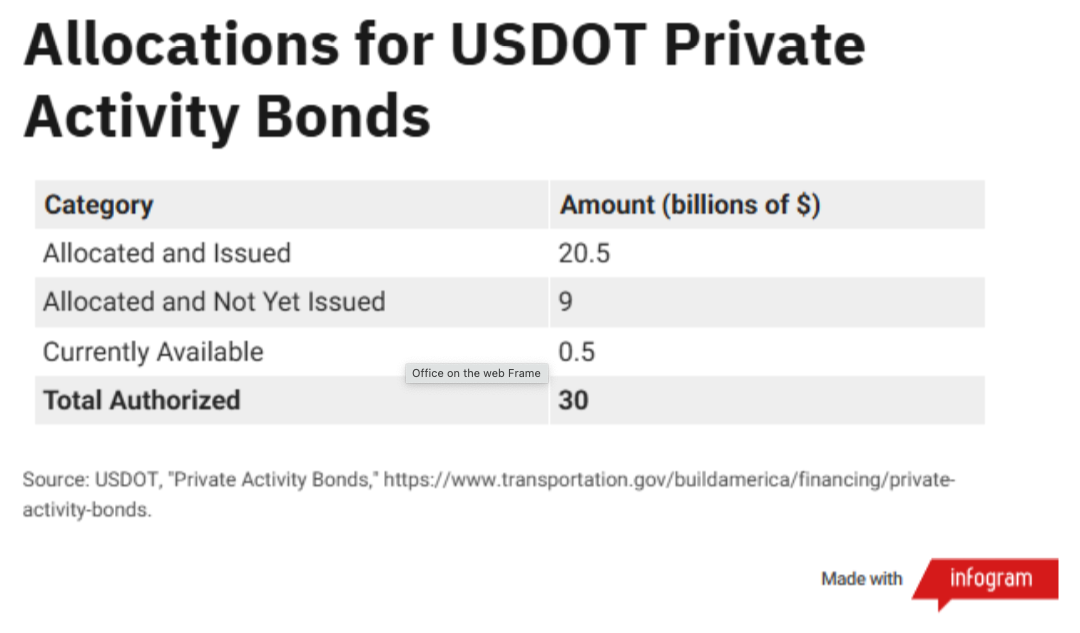

Private Activity Bonds are bonds issued on behalf of the government for the purpose of financing a project from a private entity. PABs support private sector participation and investment in transportation projects. Rail projects have benefited from the availability of PABs. For example, Brightline received $2.5 billion in Private Activity Bonds to assist in the development of its Brightline West high-speed rail line between Las Vegas and Southern California. PABs are well suited for projects that involve private companies, including public-private partnerships. For projects that only involve a public entity, this tool is less useful, unless the public entity wants to include private investment. PABs are also limited by a total dollar cap of funds available. Figure 3 shows that the majority of funding set aside for PABs has been allocated and issued.

Figure 3. Allocations for USDOT PABs

Figure 3. Allocations for USDOT PABs

Grant Programs

The IIJA provided sustained rail funding through various discretionary grant programs originally created in the FAST Act, which awards funding to eligible applicants through the competitive process. The process involves a series of steps, including application submission, project selection, grant agreement, and project implementation. The IIJA strengthened federal grant programs by boosting the levels of funding available, offering more funding for states, public agencies, Amtrak, and private railroads.

For example, the CRISI program provided significant funding for Class II and III railroads. Also known as short line railroads, these railroads were among the eligible applicants for the program. The FY24 CRISI round of funding awarded $1.29 billion across 81 projects on short line railroads. This marked the most funding awarded to short line railroads from the federal government. Short line railroads generally come into existence by purchasing unused branch lines and inheriting old and weary trackage. For short line railroads, the injection of federal dollars assisted in track improvements, bridge replacement, and rail crossing improvements, keeping short lines able to provide last/first-mile freight service to local customers.

Some projects tap into multiple funding sources. In the case of the Brightline West high-speed rail project, in which Brightline received funding from Private Activity Bonds, the Nevada Department of Transportation received $3 billion from the Federal-State Partnership program. The Nevada DOT is partnering with Brightline on this project.

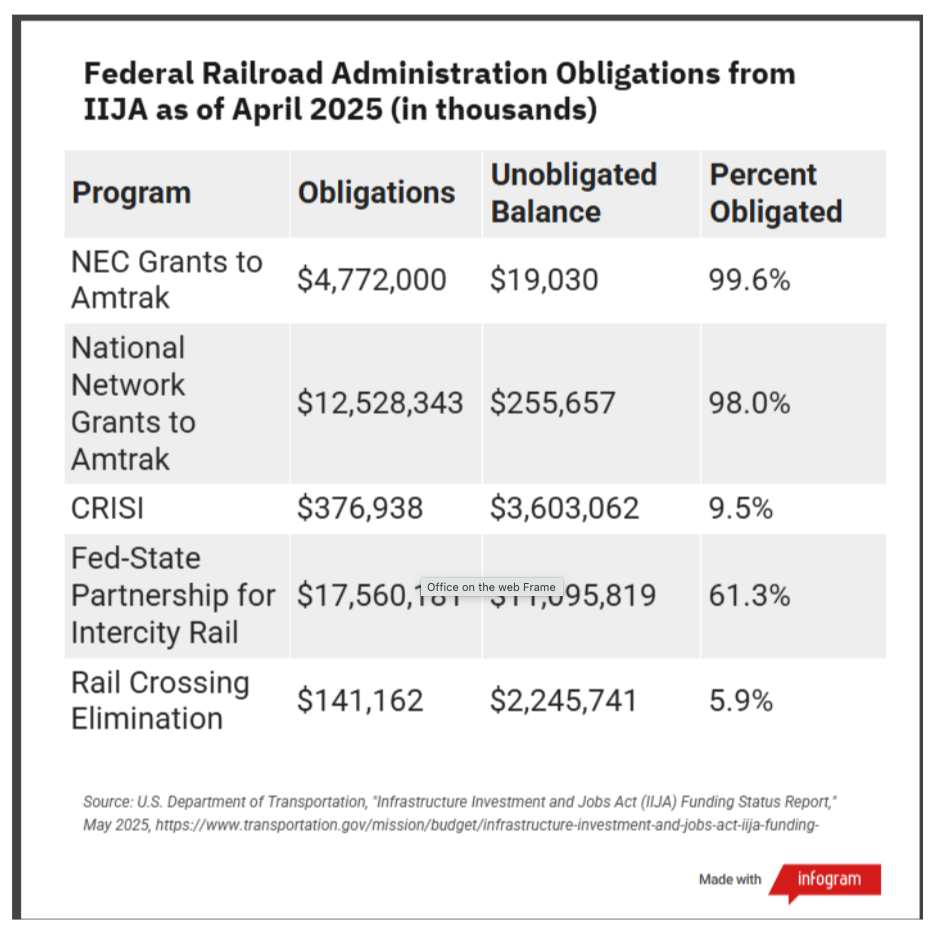

Figure 4 below shows the breakdown of total obligations for various rail grant programs in the IIJA.

Figure 4. FRA Obligations from IIJA

State Infrastructure Banks

State Infrastructure Banks are state-run financial institutions that provide loans and credit assistance to public and private sponsors of transportation and infrastructure projects (specifically highway construction, transit, and rail projects). State Infrastructure Banks were introduced as a pilot program in the National Highway System Designation Act of 1995 and expanded under TEA-21. A state infrastructure bank improves a state’s capacity to use transportation funding, by tailoring loan structures to project needs, re-use repaid loans and support private investment. SIBs can prioritize applicants whose project will make a return on investment and prioritize applicants who are more reliable in loan repayments. Similar to loan programs, projects that can repay are more suited to benefit from SIBs.

Trust Funds

In 2020, Senators Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) and Tom Udall (D-NM), and Representative Danny Davis (D-IL) proposed the Intercity Passenger Rail Trust Fund Act. This legislation would have created a dedicated source of funding for Amtrak with $5 billion annually in mandatory appropriations. However, unlike all other federal trust funds, this one had no dedicated stream of tax revenues, only a regular schedule of transfers from the General Fund. The bill envisioned that passenger rail trust fund dollars would be available to Amtrak as grants: 40 percent reserved for the Northeast Corridor and 60 percent reserved for the National Network. The goal of this proposed legislation was to allow Amtrak the ability to plan long-term projects with greater confidence. While Congress has not enacted a passenger rail trust fund to support mandatory appropriations, they were able to establish the same certainty of funding for Amtrak over five years with the advanced appropriations included in the IIJA.

Conclusion: What’s next for rail funding

Each of the surface transportation reauthorizations had more funding than the last. The FAST Act and IIJA followed the pattern of increasing federal funding and the inclusion of dedicated rail funding. The upcoming 2026 reauthorization presents another opportunity to think about transportation funding. The priorities of Congress and the Administration will influence the nature of rail funding in the next reauthorization.

The rail funding in the IIJA provided a valuable source of support for rail; excluding guaranteed rail funding or reducing funding in the upcoming reauthorization would reduce the level of federal funding available for rail projects or shift the focus away from a large federal role in rail funding. On the other hand, maintaining or increasing federal support for passenger rail would provide certainty for Amtrak and states to plan for capital projects, maintenance, or workforce development.

Another possibility is that rather than focusing on funding through grant programs at the federal level, the government may choose to focus more on private investment. Encouraging the use of private activity bonds or showing preference to private companies when giving out loans or awarding competitive grants are ways the government encourages more private investment. Encouraging private investment in rail could be done in addition to or in the absence of investment from the federal government. However, historically private investment has been best suited to freight rail and may not address the needs of Amtrak, especially on the state-supported routes in the national network.

There are numerous existing funding mechanisms and potential funding mechanisms that the government can leverage to remain a steadfast patron of rail investments. Federal investments have had a significant impact across multiple rail policy areas, shaping outcomes in the very domains rail projects were intended to address. Guaranteed rail funding contributes to more improvements in the rail network. The question for policymakers and industry professionals is twofold: to what extent the government should be involved in rail investments and how the government will leverage its tools to further rail investment should they choose to do so.