Evidence-Based Decision Making

Highway engineering, design, and operations are undergoing a dramatic shift. The rapid emergence of innovative technologies, including advanced imaging, sensors, artificial intelligence, and high-speed computing and communications, has accelerated this change.

Despite these changes and substantial investments, traffic deaths and serious injuries in the United States have remained persistently high over the past decade, while other economically developed countries have seen significant declines. Serious traffic injuries are a leading cause of lifelong disability, with high personal and societal costs. US road fatalities are characterized by the rapid increase in victims outside of vehicles. These vulnerable road users (VRU) include pedestrians, bicyclists, motorcyclists, roadside workers, and motorists involved with a disabled vehicle. Limited data exists for this VRU group because most data collection systems primarily focus on car crashes. State and federal agencies rely heavily on voluntary police-reported data, which significantly undercounts pedestrian injuries compared to reports from public health surveillance in emergency departments.

Why does the United States lag in traffic safety? A recent Consensus Study Report from the National Academy of Sciences/Transportation Research Board highlights this issue and suggests a way forward. Released last September, the report “Tackling the Road Safety Crisis: Saving Lives Through Research and Action” emphasizes that it is not just what transportation professionals do, but also how they think and act, that needs to be modernized.

The study committee was created to evaluate road safety research and offer insights into key questions: How does road safety research translate into practice? What is the evidence base that transportation professionals rely on to make sound decisions? How can we determine what is effective before and after implementation?

The Transportation Research Board (TRB) assembled an expert committee to study the process for transitioning evidence-based road safety research into practice and to recommend improvements to that process. Sponsors of the report include the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS).

The report is both enlightening and troubling. Among its findings, the study found:

- There is a lack of a scientific research basis. For example, the use of the 85th percentile “rule” for setting speed limits is deeply embedded as engineering doctrine but lacks scientific evidence.

- There is poor definition and coordination of a larger vision of road safety.

- There is an over-reliance on standards, guidelines, and professional judgement rather than evidence-based knowledge to guide practices.

- The data and data systems used are often limited and outdated. For example, police reporting of fatal crashes is voluntary, incomplete, and may take years before it is available.

- Little training in traffic safety is provided, offered, or even required in university or professional training and certification programs.

- Multidisciplinary input and collaboration are crucial to eliminating existing silos and closing knowledge gaps. Expertise needed includes law enforcement, medicine, public health, first responders, and road user specialists.

The report notes that these recommendations have been made multiple times in past Consensus Reports but have been mostly ignored. Importantly, this report provides a path forward by demonstrating how other science-based professions, with a focus on medicine, modernized their professional training, knowledge, and practices to address significant shortcomings and enhance safety, quality, and effectiveness.

In 1999, the National Academy of Sciences/Institute of Medicine (NAS/IOM) released a landmark report, “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System”. The report estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths and over one million injuries occurred annually in American hospitals due to medical errors. This groundbreaking report was poorly received by many medical professionals but triggered an awakening within the field of organized medicine and healthcare. In truth, no safety training was required for physicians; no standard definition of quality existed. Medical decision-making was guided by established standards and guidelines, as well as professional judgment. Physician autonomy was considered sacred.

In follow-up NAS/IOM reports, quality was defined by the attributes of patient-centered, safe, effective, timely, and equitable care. Shared quality metrics were defined, validated, and disseminated through a multidisciplinary national process to enable medical providers, clinicians, and facilities to measure their performance against national standards and across the country. This promotes continuous improvement, sharing of best practices, and innovation. Hospital quality metrics are available to the public online at Hospital Compare.

Medical practice has shifted from emphasizing autonomy to adopting team-based care, and evidence-based clinical pathways have been implemented for urgent conditions such as stroke, heart attack, sepsis, and trauma—significantly improving patient outcomes. Medical standards and guidelines are now flexible and regularly updated as new information becomes available. Professional judgment is strengthened by combining current research evidence with clinical expertise.

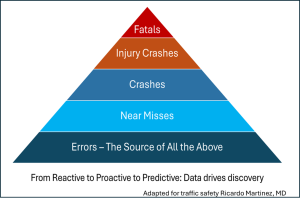

The practice of medicine is information-intensive, which is crucial for applying science to human health. Around 2010, the transition from paper medical records to digital data, along with widespread digital imaging, connectivity, and analytics, quickly expanded insights, collaboration, and innovation. Medical practices shifted from a reactive to a proactive approach as research identified early patterns and signals that predict disease. Increased reporting of potential errors helps health professionals recognize causal patterns leading to patient harm, develop predictive tools, and redesign system processes before hazards or diseases emerge. Proactive prevention is essential for health and safety. These practices similarly apply to transportation planning, design, implementation, operations, and safety.

Transportation professionals stand at a pivotal moment—equipped to drive transformative change in their field and elevate their already profound impact on society. The central challenge lies not merely in refining practices but in boldly reengineering the profession itself. Yet the pathway forward is unmistakable. With decisive leadership and visionary direction from public and private organizations, academic institutions, and professional associations, the profession can accelerate its transition toward an evidence-based, effective, efficient, and safe transportation system. This is an extraordinary opportunity to redefine the future of mobility, strengthen public trust, and deliver lasting benefits for generations to come.