Estimating Transportation Costs with Confidence

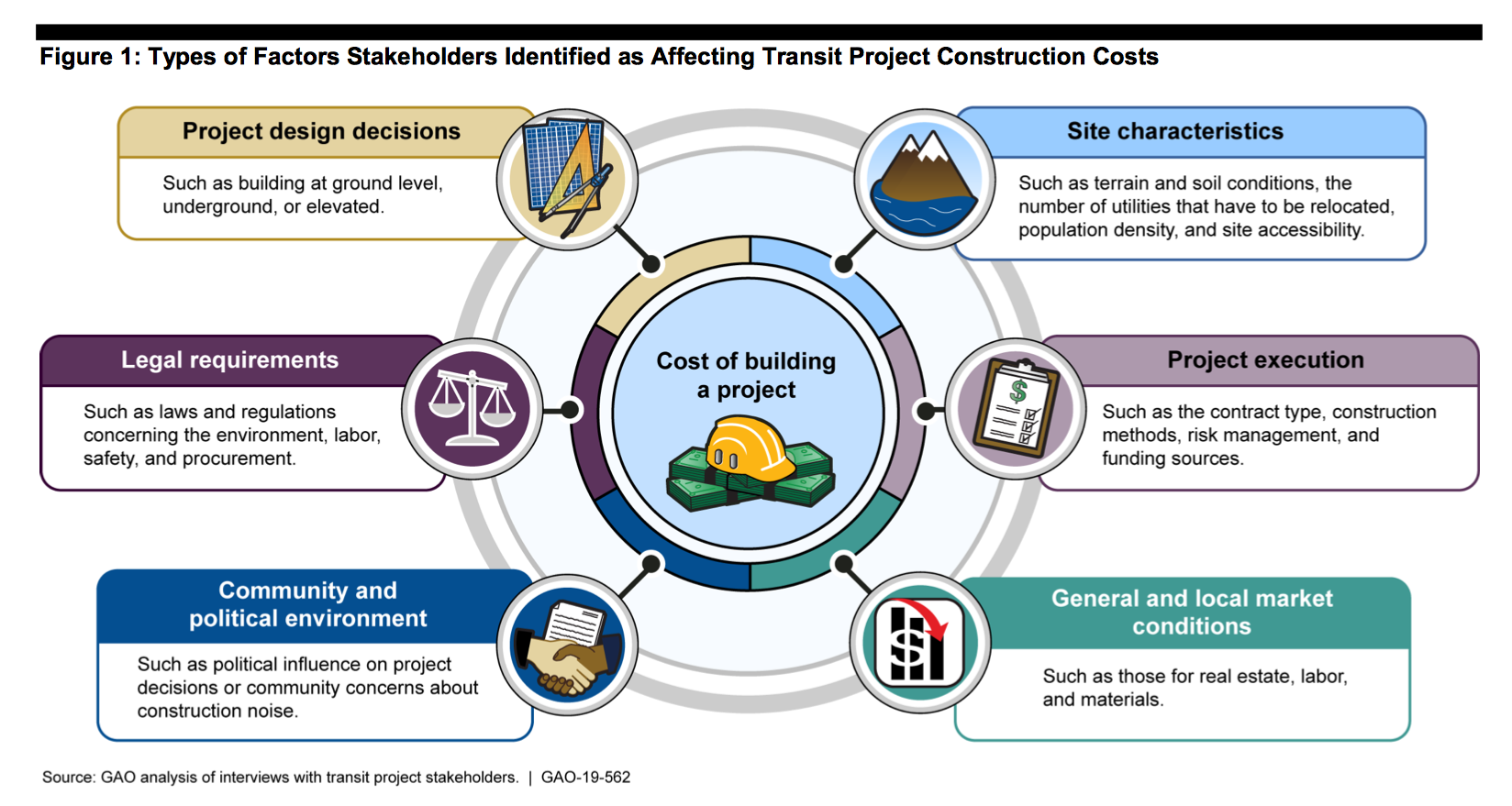

Large transportation projects are inherently complicated, and take years to plan and construct. Arguably, developing accurate estimates of their construction costs is even more challenging than predicting Super Bowl scores and election results. As shown in the infographic below, a wide variety of often interrelated factors can affect a project’s cost.

This week, Eno hosted a webinar titled “Estimating Transportation Costs with Confidence: Lessons from the Experts.” The topic is always timely because policy makers rely upon estimates of capital and operating costs to prioritize and select transportation projects. Estimating costs accurately is important so that transportation agencies and their stakeholders are not blindsided by cost increases and forced to jettison important initiatives.

This week, Eno hosted a webinar titled “Estimating Transportation Costs with Confidence: Lessons from the Experts.” The topic is always timely because policy makers rely upon estimates of capital and operating costs to prioritize and select transportation projects. Estimating costs accurately is important so that transportation agencies and their stakeholders are not blindsided by cost increases and forced to jettison important initiatives.

Cost estimators face a wide range of challenges when they prepare estimates. Surprises can range from unexpected site conditions to conflict among stakeholders. Likewise, inflation can wreak havoc with budgets; construction costs are now more than three times higher than they were 20 years ago.

On Eno’s webinar, four experts from the public, private and academic sectors — Alan Keizur, Rufus Alester, Kelly McNutt, and Eric Goldwyn — revealed strategies that transportation officials and contractors are using to improve their cost estimates. They discussed how agencies are building stakeholder confidence, prioritizing projects more effectively, and increasing the likelihood that projects are delivered within budget.

Alan Keizur, a senior technical principal at WSP, has completed cost and schedule risk assessments for more than 250 infrastructure projects. He walked the attendees through an example of a ten-year project development timeline, and how cost estimates change as a project moves from planning to preliminary design and environmental review, and then to final design, contract procurement, and finally to the construction phase. The timeline and sequence of activities may differ depending on the project delivery method selected by the owner.

Cost estimators, he explained, typically develop rough engineer’s estimates in the early stages of project development by identifying the units, quantity, and unit price of each major cost element. For example, the estimated (rough) cost of a new bridge would be $5,000,000 if the bridge deck surface area is 10,000 square feet and the unit cost is $500 per square foot. Cost estimates include both the transportation agency and the contractor’s costs, and account for anticipated inflation. A contingency amount is also typically added to account for uncertainties and risks.

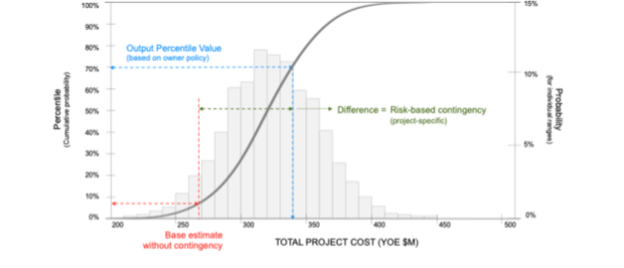

Many public transportation agencies are utilizing risk-based cost estimation approaches which produce a range of potential project costs, from pessimistic to optimistic, rather than deterministic (single number) estimates. Using the graph below, Keizur explained how a project estimate might range from approximately $200 million to $450 million. Transportation agencies, he said, commonly select a budgetary target that falls at or near the 70th percentile level (which represents a 70 percent likelihood of not being exceeded), which would be about $340 million in this example. However, some agencies are more risk averse and may use a higher cost estimate.

Rufus Alester, the deputy executive officer for program management at LA Metro, has led teams across the globe on airport, canal, high speed rail, and regional transit projects. He discussed how transportation agencies use cost estimates for decision making, budget development, financial planning, and performance measurement.

Cost estimates, he explained, provide critical data for making informed decisions and help agencies evaluate options and prioritize project elements. Cost estimates help agencies develop realistic project budgets, determine a project’s financial feasibility, and select how funds will be allocated to different project components. Cost estimates also help agencies secure funding, plan for contingencies, and manage cash flow. They also serve as benchmarks for measuring project performance, enabling agencies to identify cost overruns and take corrective actions, where appropriate.

Kelly McNutt, principal of KMC Construction Consulting, has developed cost estimates for a wide range of highway, transit, and port projects. She provides a different perspective than Keizur and Alester because of her construction industry background. She uses a production-based estimating approach which starts by defining the project scope, quantifying all components and identifying tasks necessary to construct the work. Using historical data and industry standards, she estimates time, labor, and equipment needs, and then calculates anticipated costs by factoring in materials, wages, overhead, and contingencies. She adjusts her estimates for location, market conditions, and risks. She explained how she considers a myriad of factors including temporary work involved, construction schedules, and staff requirements.

Eric Goldywn, an NYU professor, leads a transportation research team at the Marron Institute of Urban Management. He has worked with Eno on studies that revealed how transportation projects in the U.S. cost far more than in other countries. Goldwyn talked about how standardization can both reduce costs and lead to more reliable cost estimates. For example, if transit agencies build stations of similar size and features then they will have a better understanding of the quantities and units that are going to be needed.

Uncertainties

When homeowners renovate their kitchens, they are often surprised to learn — after beginning demolition — that they will have to replace the electric wiring and install new plumbing. Likewise, transportation agencies face uncertainties before they begin their projects.

Keizur said certain types of projects tend to have greater uncertainties and larger risks than others. For example, urban construction tends to be more complex than rural construction because work has to proceed around existing infrastructure, utilities, and buildings. Risks also tend to increase, he explained, when new technologies are used and when many stakeholders are involved.

Owners, engineers, and contractors can all offer valuable perspectives to help create more reliable cost estimates, according to McNutt. For example, before renovating a kitchen, the owner might reveal that the pipes freeze every January, indicating that new insulation is needed. Engineers will understand all the construction requirements, while a contractor might suggest cutting out some of the drywall to better understand existing conditions before the owner finalizes the cost estimate.

Alester said costs can significantly increase when abandoned utilities are uncovered and when cooperation from other property owners, such as freight railroads, is required. It is important, he emphasized, to set contingency levels based on the risks that are involved. After Goldwyn suggested that agencies should establish agreements with third parties early on to reduce uncertainty, Alester said that was exactly what LA Metro has been doing with its municipal partners and utility companies.

Honolulu

Weather forecasters, stock analysts, and economists do not have crystal balls. Neither do cost estimators. For example, in 2012, the Federal Transit Administration agreed to provide the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transit nearly $1.6 billion to construct a 20-mile rail line, a project whose cost was estimated at $5.1 billion. Since then the price tag has more than doubled and now exceeds $12 billion.

The panelists explained how this project had a great deal of risk because of uncertainties associated with numerous issues such as the location of lava rock and existing utilities. Contracts were not managed effectively and the project faced numerous unexpected delays. For example, construction was halted and the project subsequently set back for a year-and-a-half, after the Hawaii Supreme Court found that city and state officials did not complete a required archaeological study relating to native Hawaiian burial sites.

McNutt said, “I’d say that the real challenge there was getting everybody including the owner to live within the four corners of the contract.” A transportation agency needs to have a team that understands its project, she said, and has the resources to respond when faced with major problems. Keizur referred to a “vicious cycle.” Delays lead to cost increases, which leads to delays obtaining more funding, which leads to even more delays and cost increases.

To learn more about cost estimating, see FHWA’s Cost Estimating Resources, Cost Estimation for FTA Funded Transit Projects, and Cost Estimating for Major Projects.