DOT Explores Killing Dedicated Fuel Tax Revenues Now Going to Mass Transit

A very old idea has resurfaced. According to an article in POLITICO PRO, the Department of Transportation has asked the White House for permission to throw mass transit funding out of the Highway Trust Fund as part of its surface transportation reauthorization bill. This proposal would have two pieces:

- Repeal of the ability of state and local highway funding recipients to choose to use some of their highway formula funding for mass transit projects (referred to as “flex” transfers), and

- Abolition of the Mass Transit Account of the Highway Trust Fund, with the receipts of the 2.86 cents per gallon of federal motor fuel taxes currently deposited in the Mass Transit Account instead going to the Highway Account.

Congress specifically rejected this proposal 21 years ago, and then again 13 years ago, and the math (both in terms of the vote count in Congress and again in terms of how little money the proposal would actually save) has only gotten worse since then.

Flex

The federal-aid highways program was put on hold during World War II. After the program resumed, the program was put on a two-year reauthorization cycle starting in 1948, like clockwork. Until the 13th consecutive reauthorization bill, in 1972. That year, urban-minded legislators refused to vote for an extension of the highway program unless some of the Highway Trust Fund’s seemingly limitless resources were allowed to be spent on mass transit funding, a proposal pushed by President Nixon and his Transportation Secretary John Volpe.

This idea – the federal manifestation of the “freeway revolt” that started at the urban level in the early 1960s – had even worked its way into the 1972 Democratic Party platform, which called for “a single Transportation Trust Fund, to replace the Highway Trust Fund, with such additional funds as necessary to meet our transportation crisis substantially from federal resources. This fund will allocate monies for capital projects on a regional basis, permitting each region to determine its own needs under guidelines that will ensure a balanced transportation system and adequate funding of mass transit facilities.”

In 1972, the Senate (traditionally the chamber more supportive of mass transit) voted, 48 to 26, to adopt the Cooper-Muskie amendment allowing recipients of federal-aid urban highway formula funding the flexibility to use that highway funding on mass transit projects (highway or rail) instead. The House refused to go along, and on the very last day of the annual session, a House-Senate conference committee punted and approved a 1-year extension of the highway program without Cooper-Muskie, which was adopted by the Senate by voice vote. However, enough House members had already left town that when the late, great Rep. John T. Myers (R-IN) demanded a quorum call, only 154 members were present, so the House could do nothing but adjourn for the year.

When the next Congress convened in 1973, states were starting to run out of highway funding, and the nationwide redistricting under the new “one man, one vote” standard had resulted in a markedly more urban tilt in the House. The result was the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1973, section 121 of which allowed federal highway funding recipients to choose to use their highway money to build bus lanes and bus facilities immediately, and to use their highway funding starting in FY 1975 for bus purchases and starting in FY 1976 for rail-based mass transit.

(For much, and I do mean much, more information, see Richard Weingroff’s Busting the Trust: Unraveling the Highway Trust Fund 1968-1978.)

Today, the descendants of that provision are still in law. The Surface Transportation Block Grant Program and the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Program each have built-in blanket ability to choose any kind of public transportation project for funding, and the much larger National Highway Performance Program can be used for some transit projects under some circumstances. Over the last ten years, states and MPOs have averaged $1.27 billion per year in such “flex” funding in net terms. (States and MPOs also have the flexibility to spend mass transit money on highway projects in some circumstances, but there is a lot less of that going on.

Once a state or MPO decides to use highway money for a mass transit project (or vice versa), the contract authority is transferred from FHWA to FTA for administration, and at the same time, an identical amount of Highway Trust Fund cash balance is transferred from the Highway Account to the Mass Transit Account (or vice versa). See the last few years of Table FE-1 for those transfer totals.

The problem with getting rid of “flex,” 52 years on, is twofold. First, it would represent significant new federal micromanagement of state and local funding decisions, and the current Administration has presented itself, generally, as wanting to free state and local governments from the federal bureaucratic yoke.

But more importantly, abolishing “flex” transfers won’t save federal taxpayers a single dollar. While the transfer of cash balances from the Highway Account to the Mass Transit Account shows up as a line-item in the presentations of Trust Fund cash flow, there is also an equal amount of outlays deducted from the Highway Account’s outlay total and added to the Mass Transit Account’s outlay total in all such presentations (it just doesn’t merit a separate line item).

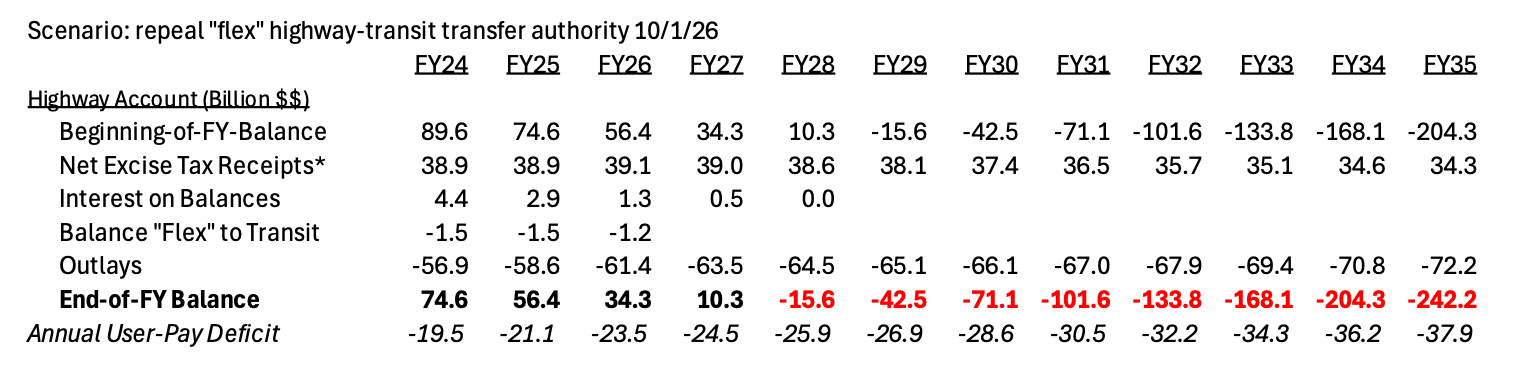

For example, here is the Congressional Budget Office’s most recent HTF forecast for the Highway Account, adjusted for actual FY 2025 year-end cash flow. CBO assumes a flat $1.2 billion per year of future flex transfers, since the actual amount is unknowable beforehand.

Here are the same data if you get rid of flex transfers starting at the end of the IIJA authorization – balance removals are eliminated, but outlays go up by the same amount, because states and localities spend that money on highways instead of transit projects, and the bottom line does not move.

Getting rid of flex transfers will result in states and localities spending less federal money on mass transit projects, but it won’t contribute a single dime towards fixing the Highway Trust Fund’s deep revenue hole.

The Mass Transit Account

By the time the highway program needed reauthorization in 1982, the Great Inflation had ravaged the buying power of the four cent-per-gallon motor fuels taxes (set at that level back in 1959) to the point that something had to give. Again, urban-oriented legislators flexed their muscle and refused to reauthorize the highway program unless they got a significant concession.

President Reagan eventually agreed, and the motor fuels taxes were increased from four to nine cents per gallon, with one penny (20 percent of the increase) going to a new Mass Transit Account, which would provide new contract authority expressly for transit purposes for the first time.

(Back in 2015, I spent a week at the Reagan Library and another week perusing the Donald T. Regan papers at the Library of Congress and wrote a monograph on what I had learned, “Reagan Devolution: The Real Story of the 1982 Gas Tax Increase,” for those who want the full story. Or, for those who don’t like to read 35-page research papers, there’s an accompanying slide presentation that gives you the outline, with lots of colorful photos and charts.)

Every subsequent increase in federal motor fuels taxes (1990 and 1993) has also set aside 20 percent of that increase for transit, so today, the proceeds of 2.86 cents per gallon of gasoline and diesel fuel are deposited in the Mass Transit Account. These tax deposits have averaged $5.25 billion per year over the last ten years. CBO’s last projection was that the 2.86 cents per gallon would bring in $44.1 billion over the ten-year period from FY 2026-2035, which the Administration would evidently prefer to deposit in the Highway Account instead.

In this century, there have been two serious efforts to do this (abolish the Mass Transit Account and redivert that 2.86 cents per gallon of fuel tax back to highways). The first was in 2003. I remember Dawn Levy, the highway staffer for Finance Committee ranking member Max Baucus (D-MT), sitting me down in the Dirksen Cafeteria in spring 2003 to describe her boss’s proposal to get rid of the Mass Transit Account and replace it with some sort of GF-guaranteed bond issuance to fund mass transit. She wrote it all out on a legal pad with a ball point pen with purple ink, I remember.

Finance Chairman Charles Grassley (R-IA) went along with it, but the policy committees that wrote the rest of the transportation bill (EPW/Commerce/Banking) would not, so no bill advanced and they went to a series of short-term extensions instead. Baucus said at the Finance markup of the first extension that he regretted his colleagues’ rejection of “changing the rules so that…the Highway Trust Fund truly gets all the dollars that are due to it from the federal gasoline tax. As we all know, some of it goes to mass transit, even though mass transit does not contribute.” The eventual SAFETEA-LU reauthorization law in 2005 did not reduce or otherwise alter transit’s share of tax revenues.

Fast forward to 2011-2012. Republicans had just taken back control of the House and new Transportation and Infrastructure chairman John Mica (R-FL) wanted to take away mass transit’s dedicated fuel taxes. His bill would have thrown the CMAQ, Puerto Rico/territorial, and ferry boat programs out of the Highway Account as well, renamed the Mass Transit Account the “Alternative Transportation Account,” and funded mass transit/CMAQ/etc. with a one-time $40 billion General Fund transfer, to be paid for by some kind of one-time federal employee pension reform offset.

The vote on the bill in the T&I Committee was 29 to 24, almost totally party-line (Tom Petri (R-WI) voted “no”), but several of the “yes” votes in committee told Mica that they would be “no” votes on the House floor unless transit retained its guaranteed revenue stream. Steve LaTourette (R-OH) in particular was preparing such an amendment and trying to get GOP support. In their dissenting views in the committee report, T&I Democrats said “This short-sighted change to appease a minority of the Republican caucus who insist on cutting Federal spending at any cost is an inconceivable step backwards in surface transportation policy.”

By the time the bill got to the Rules Committee in February 2012, it had been rolled into a larger, leadership-driven package with Keystone XL pipeline permitting and offshore oil drilling bills (H.R. 7). President Obama promised a veto, which helped ensure unanimous Democratic opposition, and LaTourette (RIP, buddy) and the transit lobby were able to steal away enough Republicans to ensure that the Speaker and Mica never had the votes to bring H.R. 7 to the floor.

Instead, the Speaker broke up the bill and passed the energy provisions separately, then the House mostly went along with the Senate’s two-year bill which became MAP-21 and which made no changes to mass transit’s claim on motor fuel tax revenues.

And remember: at this point in time (early 2012), Republicans held 242 seats in the House, yet they still lacked the votes to bring a bill abolishing the Mass Transit Account’s dedicated revenue stream to the House floor. This means that there were around two dozen Republican “no” votes on the whip check at minimum. Today, Republicans hold just 219 seats in the House, meaning that they can only lose two or three votes in the face of united Democratic opposition and still prevail on a vote.

Even though the current House Republican Conference is more ideologically united than the one in 2012, and they share a pan-ideological deference to the President that is something new, there is no evidence that 218 Republicans will support abolition of the Mass Transit Account, even if the President decides to adopt it as a personal cause (and sticks with it).

Abolishing the Transit Account becomes an even harder sell once you look at the math. Just because your state used to be a transit donor, don’t be 100 percent certain that is still the case. Per DOT reporting, Texas pays about $542 million per year in fuel taxes into the Mass Transit Account, but in FY 2025, the Lone Star State received $701.8 million in formula funding from the Mass Transit Account (the $722.3 million shown here minus the 20.19 percent of State of Good Repair formula and the 11.19 percent of Elderly/Disabled formula that comes from IIJA Division J General Fund money).

For every dollar that Texas pays into the Mass Transit Account, they get $1.30 back in mass transit formula funding. This is an even better deal than Texas gets from the Highway Account, where according to FHWA in FY 2025 they got back only $1.22 in highway formula funding for every $1.00 in fuel taxes they paid into the Account.

(This is primarily an indicator of just how badly the Mass Transit Account now relies on deficit-funded General Fund bailouts. As the late Mort Downey used to say, these days, the only donor state is the People’s Republic of China.)

Here’s another problem: transferring the receipts of transit’s 2.86 cents per gallon of motor fuel taxes to highways won’t go very far towards filling the Highway Account’s revenue hole.

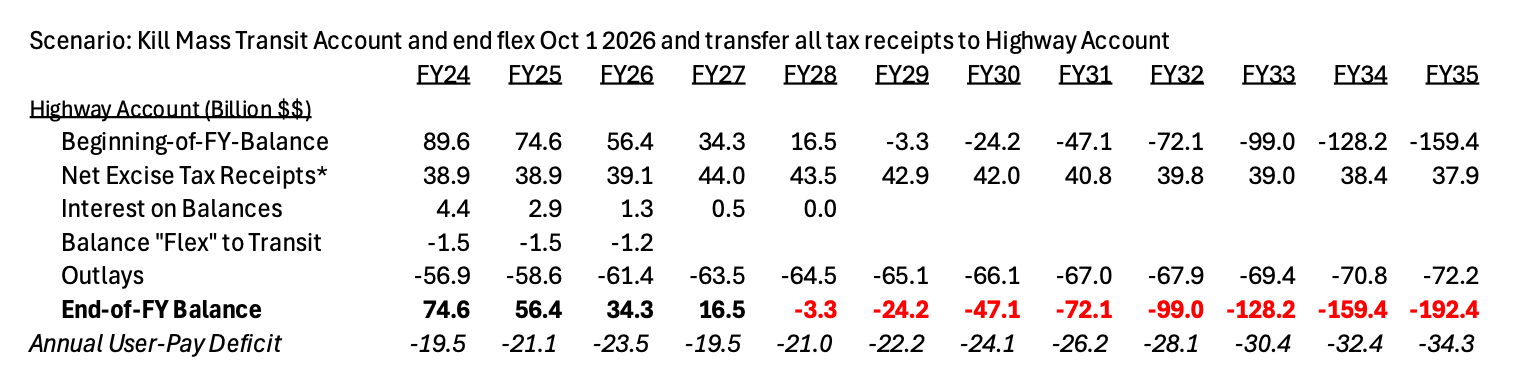

You saw above that the baseline 10-year revenue hole for the Highway Account is $242 billion, and the Account is projected to hit insolvency in FY 2028. Here is the same CBO data adjusted to kill flex transfers and put all of the Mass Transit Account’s tax receipts back in the Highway Account starting in October 2026.

The 10-year revenue hole is still $192 billion deep and the Account still runs dry in FY 2028.

But wait, you say, the last CBO baseline assumed all electric vehicle tax incentives and all EPA and NHTSA rules to force a quick EV transition would stay on the books. Since those have all been repealed, the next baseline won’t show gasoline tax receipts fading away so fast, will it? That is probably correct. So let’s assume that we kill flex, take back the Transit Account’s share, and then hold tax receipts flat at the FY27 level forever – no more switching to EVs.

That won’t do it either. You still run out of money in FY 2028 and the ten-year hole is still $176 billion deep.

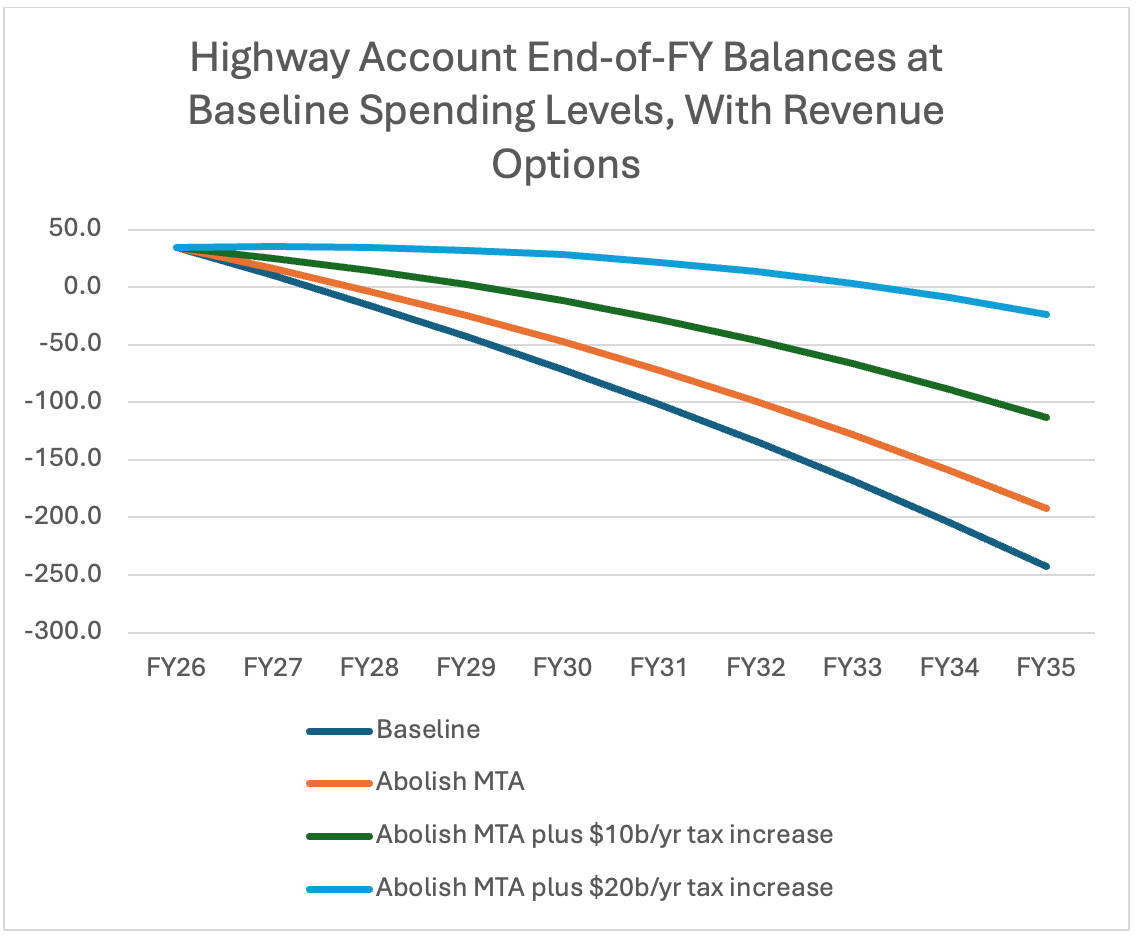

If you are going to keep the Highway Account solvent, you need to cut spending well below IIJA levels, or else raise taxes or keep putting in General Fund bailouts, even if you kill mass transit dead. Here is how far an extra $10 billion per year in new taxes would get you, on top of ending flex and ending the Transit Account:

Congratulations. Your $10 billion per year tax increase has postponed the Highway Account’s insolvency by one year and reduced the revenue hole to $113 billion over 10 years. But you still can’t write a five-year bill on that. How about $20 billion per year in new taxes (on top of killing abolishing flex transfers and killing the transit account)?

That’s more like it. $20 billion per year in new taxes over baseline would keep highways solvent for a six year bill plus a bit, but would not completely eliminate the downwards trend. If you just wanted a five-year bill at baseline spending levels and let it drop off a cliff afterwards (the recent practice), you would need to kill flex and the Transit Account and raise around $16-17 billion per year of new taxes, or General Fund bailouts.

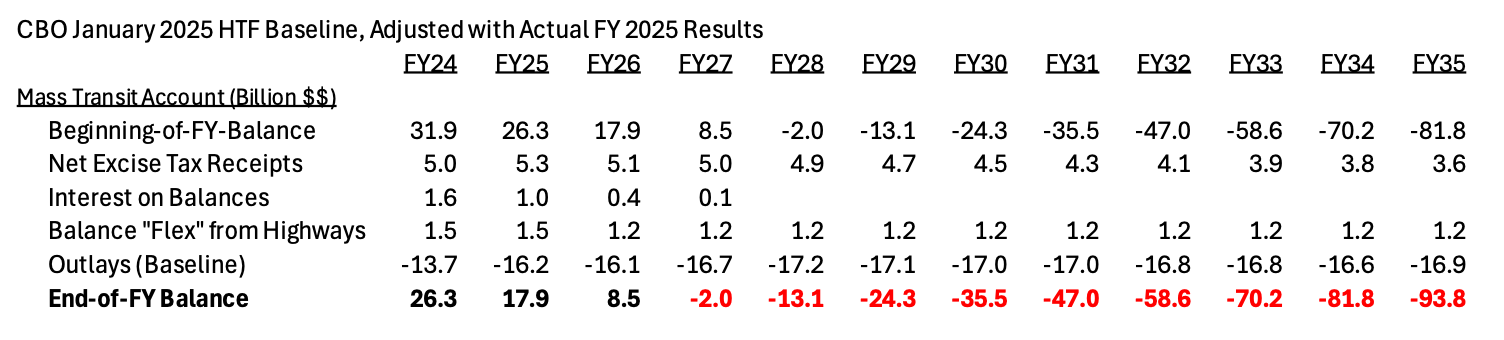

This leaves one last technical problem – you can’t just kill a capital program overnight. These things spend very slowly. Even if you cancel all new Mass Transit Account spending obligations on October 1, 2026, and never obligate a dime in the future from any source, the slow-spending contracts and grant agreements signed prior to that date remain valid and bills for reimbursement still come in. Here is the most recent CBO baseline for the Mass Transit Account:

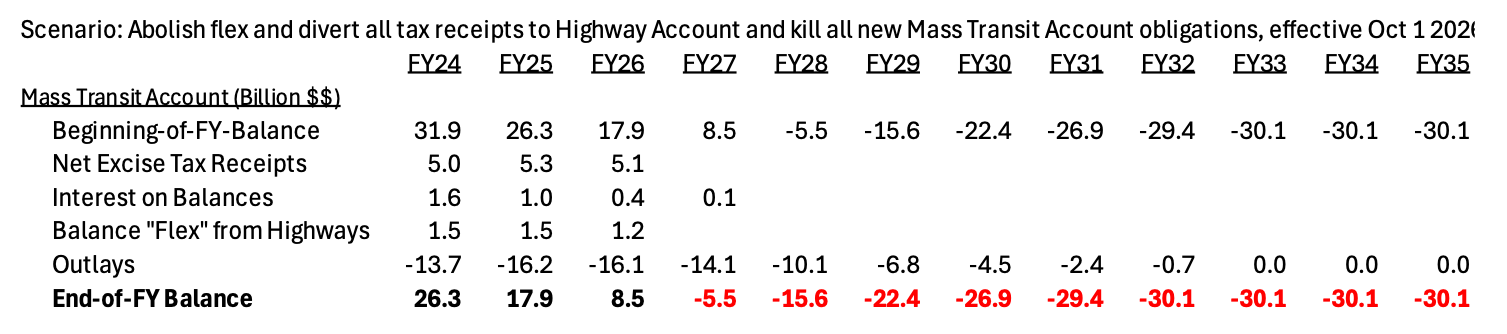

And here is an alternate scenario, where we kill flex and take away the taxes on October 1, 2026 and also stop signing new spending obligations out of the Account and just wait for the prior commitments to spend out:

Even if you shut it down the day after the IIJA ends, the Mass Transit Account would need an additional $30 billion General Fund bailout in order for the FTA to keep paying validly incurred bills.

Summary

Has spending highway user taxes on mass transit ever been completely consistent with the “direct benefit” principle that underlies user-pay trust funds? Not really.

Is the Mass Transit Account much more overleveraged, relative to its dedicated revenue stream, than the Highway Account? Most certainly, and unless Congress is willing to increase taxes or rearrange the split of existing taxes, transit must see a greater percentage reduction in its Trust Fund spending in the next reauthorization bill than must highways.

Is abolishing the Mass Transit Account and taking away state/local “flex” transfer authority politically feasible? No, it wasn’t feasible when Republicans had 242 House seats and isn’t going to be feasible now that they only hold 219 seats, some of which are in uniquely transit-dependent places like Staten Island, Long Island, and Westchester County.

Would abolishing the Mass Transit Account bring enough fuel tax dollars back to highways to make a real dent in the Highway Account’s revenue problem? Not really. In the fiscal year that just ended, Congress (through the IIJA) created $64.0 billion in Highway Account contract authority. Even if you had abolished the Mass Transit Account at the start of the year, total user tax receipts were only $44.2 billion. The math is brutal, but bailout after bailout has allowed the overleveraging of both the Highway Account and the Mass Transit Account to get wildly out of hand.