Barack Obama: (2009-2017): Restarting the Economy

This article is a part of our series From Lighthouses to Electric Chargers: A Presidential Series on Transportation Innovations

It was the biggest economic meltdown since the Great Depression. Subprime mortgages, upside-down car loans and the collapse of Lehman Brothers accelerated a seemingly bottomless nosedive for the US economy throughout 2008. GM and Chrysler were already bankrupt. Household net worth fell $11.5 TRILLION (17.3%). Nationwide monthly job losses were 433,000 in September 2008, accelerating to 818,000 in January 2009 when President Obama first took the oath of office.

It was the biggest economic meltdown since the Great Depression. Subprime mortgages, upside-down car loans and the collapse of Lehman Brothers accelerated a seemingly bottomless nosedive for the US economy throughout 2008. GM and Chrysler were already bankrupt. Household net worth fell $11.5 TRILLION (17.3%). Nationwide monthly job losses were 433,000 in September 2008, accelerating to 818,000 in January 2009 when President Obama first took the oath of office.

My professional vantage point for this economic freefall was as a state DOT Secretary. At the Maryland Department of Transportation, our capital program fell off a cliff throughout 2008 as motor fuel tax revenues, vehicle registrations, port revenues, transit farebox recovery and even airport landing fees all took a nosedive. We were dramatically reducing our project bid schedule and imploring contractors not to lay off workers.

State DOT CEOs were carefully following the work of President-elect Obama’s transition team and hanging on every word for any sign of federal help. In Maryland, we put together a high/low mix of projects that were either transformative, or more mundane but bid-ready for immediate impact. The urgency was palpable: we stretched the rules and provisionally awarded contracts, subject to federal funding, for the first time. And when the Recovery Act was signed, we had the first project in the nation underway the next day– a repaving project on an arterial road into the District of Columbia. This was followed by a plethora of other quick implementation projects.

In a cosmic twist, within weeks I was in the Obama administration confirmed as USDOT Deputy Secretary, and Job 1 was to help my former state CEO colleagues get similar projects from coast to coast out the door.

John Porcari and President Obama aboard Air Force One enroute to a tour of the new Port of Miami tunnel, March 29, 2013.

This was not going to be your father’s DOT. The defining transportation imperative and the energy of most of President Obama’s first term was clearly going to be stabilizing and jump-starting the economy, in our case through projects of every description—and varying merit.

Ray LaHood, President Obama’s choice for transportation secretary, was a Republican Congressman from the Peoria, Illinois area, moderate, thoughtful and well-respected on both sides of the aisle. He enjoyed a close relationship with Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel and the president. LaHood also served as a bridge to Republicans in both houses for the president.

Cover of Secretary LaHood’s book: “Seeking Bipartisanship: My Life in Politics.”

For Secretary LaHood and the rest of the newly-minted DOT leadership team, the response to this national economic emergency was two-fold: get projects like the one in Maryland under construction and employing workers as quickly as possible with the recently passed American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), popularly known as the stimulus bill, and stabilize America’s auto industry through the innovative CARS Act, universally known as Cash for Clunkers.

The $787 billion Recovery Act, signed by President Obama on February 17, 2009, provided $48.1 billion in transportation stimulus funding: $27.5 for highways; $6.9 for transit; $8 billion for passenger rail, including, for the first time, high-speed rail; $1.3 billion for Amtrak; $1.1 billion for airports; and, also for the first time, $1.5 billion in discretionary grants directly to states, cities, counties and towns (more on that later). “Shovel-ready” projects emphasized speed in getting projects underway and people back to work.

Estimates of jobs retained and created for every project were dutifully reported weekly online to the public and to the White House, where a line-by-line project review process led by Vice President Biden and his chief of staff, Ron Klain, had the various deputy secretaries lugging binders of projects into what seemed like a regularly scheduled meeting with the Headmaster. Later, long after most had forgotten that the purpose of the Recovery Act was to put people to work immediately and the actual transportation projects built were an added bonus, would come the discussion of “shovel-worthy” projects versus “shovel-ready”.

Every presidential administration has its own character and Modus Operandi. An early lesson in presidential leadership was imprinted during my first Recovery Act meeting in the Roosevelt Room at the White House with “no drama Obama”, assorted Cabinet members and senior White House appointees. As I did my best to blend into the background, President Obama listened to every opinion that was proffered, then systematically solicited input from everyone who did not speak up. Only then did he voice an opinion. When you’re the smartest one in the room, you don’t have to strut.

The second short-term transportation prong for halting our economic cliff-dive was the Car Allowance Rebate System (CARS), better known as the Cash for Clunkers program, championed by Ohio Congresswoman Betty Sutton, provided a $3500 or $4500 rebate when trading in old gas guzzlers for more fuel-efficient new vehicles. The vehicles traded in were required to have their engines immobilized by a Sodium Silicate solution, which, according to NHTSA lore, seized every engine during testing except for those found in the ancient Volvo 240 series.

This $1 billion program was projected to result in the sale of approximately 75,000 new vehicles. When the application process opened on July 1, 2009, DOT was flooded with applications; the $1 billion was fully subscribed by July 30th. After a well-known national financial institution (ahem, you know who you are!) utterly failed to scale up the administrative processing of the rebate applications, DOT General Counsel Bob Rivkin led a crash effort to process the applications, involving the training of DOT career staff and political appointees alike, contracting with the IRS for staff augmentation, and setting up tables in the DOT lobby to process the applications. Congress quickly added an additional $2 billion to the program, and 677,000 vehicles were ultimately sold under the program, in a year in which the annual vehicle sales rate had plummeted by 6 million vehicles.

Every crisis creates opportunity, and the Great Recession and subsequent Recovery Act created two big ones for DOT: the TIGER (Transportation Improvements Generating Economic Recovery) grants, and the high speed rail program. Both programs fundamentally broadened the mission of USDOT.

The Recovery Act’s $1.5 billion discretionary grant program was quickly packaged as the TIGER competitive grant program, intended in part by Congress to establish an end run around the then-ban on earmarks for specific projects. In its execution, however, the TIGER grant awards served as proofs of concept for whole new categories of federal infrastructure investment: complete streets projects, small town Main Street rebuilding, intermodal terminals, electric buses, traffic signal prioritization, the Atlanta Beltline, Bureau of Indian Affairs and National & National Park Service road projects, and even the elimination or capping of existing highway facilities. More broadly, the TIGER merit-based grant program created a direct federal-local funding relationship for the first time.

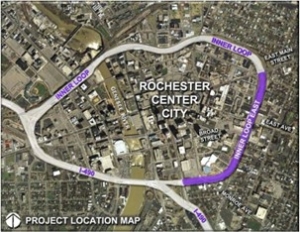

One early example of the transformative power of these TIGER grants— and the federal-local partnership that it enabled— was with my hometown of Rochester, NY, which had constructed a beltway around its central business district in the late 1950s and early 1960s called the Inner Loop. When Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller officially opened the last segment of this concrete necklace around the city in 1965, Rochester was a city of 330,000 citizens. The Inner Loop never achieved the traffic volumes originally envisioned, and when then-Mayor (later Lt. Governor) Bob Duffy applied to USDOT for a TIGER grant in 2013, the City’s population was approximately 210,000, ravaged by the loss of jobs at leading employers Kodak and Xerox. Mayor Duffy and his city council proposed to fill in the eastern section of the Inner Loop with Lake Ontario dredge spoils and construction rubble, reconnecting the central business district to the city’s east side arts and entertainment district with new businesses, apartments and recreational facilities. The $18 million TIGER grant that made this $23.6 million project possible later became the national prototype for reconnecting communities efforts in Pittsburgh, New Orleans, Syracuse, Tulsa, Oakland, and other cities, and a separate Reconnecting Communities program for second term DOT Secretary Anthony Foxx.

Map of Inner Loop East and photo of land made available for development. Source: Federal Highway Administration

The high speed rail component of ARRA was almost an afterthought. $8 billion of high speed rail funding was inserted into the final bill at the last minute by Rahm Emanuel, the president’s chief of staff. This was “$8 billion more than we’ve ever spent on high speed rail before”, quipped LaHood at the time. California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger was one of the first out of the box with a modest-for-the-Terminator request of $4.73 billion of the $8 billion, to augment the $9.95 billion of state funds authorized in Proposition 1A the year before.

Small grant awards, geared to getting construction underway quickly, and large “Track 2” high speed intercity passenger rail projects for California ($2.6 billion), Florida ($2.4 billion), Wisconsin ($810 million), and Ohio ($400 million) were quickly awarded. However, the newly-elected Republican Governors Scott, Walker and Kasich of Florida, Wisconsin and Ohio, respectively, performatively refused these grants that their states had previously applied for. The funds were quickly reallocated and gratefully accepted by other states, but the partisan lines on high speed rail had been established. While this burst of funding served to initiate a number of projects, including the launch of the California high speed rail program, the lack of a consistent, ongoing funding source would hobble the development of higher (79-110 MPH) and high speed (110 MPH+) public and private sector rail projects for years to come.

Shortly after President Obama’s 2009 inauguration, a Colgan Air flight crashed about five miles short of the runway in Buffalo, with the loss of 50 souls. The accident investigation quickly determined that an inappropriate response to an incipient stall by the Captain, compounded by lack of situational awareness by both the Captain and First Officer, contributed to the accident. In response, President Obama signed the Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Extension Act of 2010 for the first time requiring both the Captain and First Officer to hold Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) ratings, effectively increasing the minimum flight hours required for cockpit crew members from 250 hours to 1500 hours, along with changes in training, flight duty and rest times.

Another notable aviation event during President Obama’s two terms in office was the grounding in January 2013 of the brand new Boeing 787 fleet in response to several thermal runaway incidents relating to the lithium-ion batteries used in the aircraft. This was the first grounding of an aircraft type by the FAA since the DC-10 grounding in 1979. The 787 fleet was permitted to return to service in April after improvements in manufacturing techniques and quality by the battery manufacturer and better fire containment designs were retrofitted to the fleet.

Every Secretary has a pet cause, and for Ray LaHood it was distracted driving. He labeled distracted driving a “national epidemic” and started the campaign with a Presidential Executive Order banning texting while driving in federal vehicles, followed by pledges by teen drivers, truckers and others. Ultimately, 35 states and the District of Columbia banned texting while driving through the campaign.

When former Charlotte Mayor Anthony Foxx replaced Ray LaHood as Secretary and was sworn in during President Obama’s second term on July 2, 2013, he built on and broadened some of the first term initiatives such as Reconnecting Communities, as well as building equity and climate resilience considerations into grant awards. Foxx also launched the Smart Cities Challenge, which awarded $40 million of DOT funds and $10 million of private funds to the winning city, Columbus, Ohio.

The core theme of transportation through both terms of the Obama administration was to use our nation’s transportation system as an enabler of larger goals such as economic development, quality of life, and environmental restoration. Transportation projects were a means to those ends, rather than an end in themselves. Building strong partnerships across the federal enterprise with EPA and HUD also showcased the value of working together on environmental goals and transit-oriented affordable housing.

But one has to go back to the urgency of the Great Recession—and the very real discussion at the time of potential general economic collapse— to understand how the US DOT, under the 44th president, was wielded as a pair of jumper cables to help restart our economy.

John D. Porcari served as the Deputy Secretary and twice served as Secretary of the Maryland DOT, vice president at the University of Maryland, and deputy US DOT secretary. He co-founded the Equity in Infrastructure Project and serves on boards of the Regional Plan Association and STV. He is currently a managing director at Investcorp Corsair Infrastructure Partners.