Amtrak Matches Trump Budget Request; Minds the GAAP and Revises Operations Budget Presentation

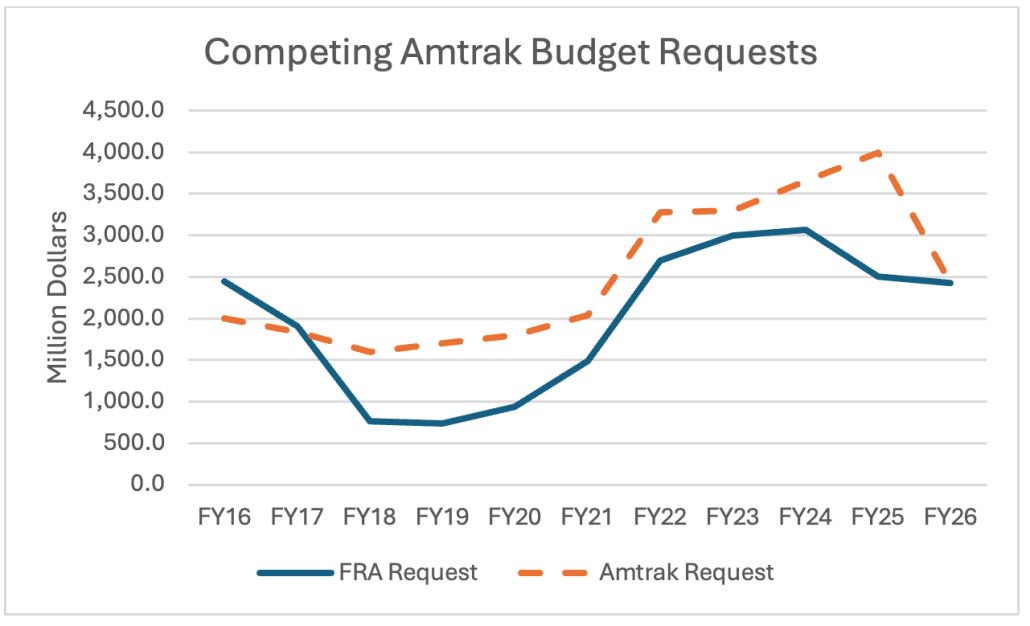

In an unusual show of synchronization with the White House, Amtrak’s budget request on its own behalf for fiscal year 2026 is, in its account totals at least, identical to the Trump Administration’s request on its behalf through the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA).

(This does not include appropriations previously made by the IIJA bipartisan infrastructure law directly to Amtrak itself or for other, competitive rail grant programs that have been awarded to Amtrak.)

Annual request

Both Amtrak and FRA are requesting $2.427 billion in new appropriations, which is just $763 thousand less than appropriated in 2024 and re-appropriated (through the year-long continuing resolution) in 2025. However, both Amtrak and FRA are showing a change in emphasis – within that $2.427 billion, $291 million is being shifted away from the Northeast Corridor and towards the remainder of the Amtrak system (the National Network).

| FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | Request | |

| Enacted | Enacted | Request | vs FY25 | |

| NEC | 1,141.4 | 1,141.4 | 850.0 | -291.4 |

| NN | 1,286.3 | 1,286.3 | 1,577.0 | +290.7 |

| Total | 2,427.8 | 2,427.8 | 2,427.0 | -0.8 |

Over the last decade, Amtrak’s funding request on its own behalf has ranged from 82 percent of the amount requested by FRA (FY 2016) to 230 percent of the FRA request (FY 2019), with Amtrak requesting an average that is 142 percent of the FRA request.

Amtrak proposes to spend this $2.427 billion in the following ways:

- $230.9 million in operating subsidies for money-losing State-Supported Route (SSR) train lines;

- $563.2 million in operating subsidies for the even more money-losing Long-Distance Route (LDR) train lines;

- $838.8 million in capital funding on the federally-owned Northeast Corridor;

- $365.5 million in capital funding for SSR lines;

- $251.3 million in capital funding for LDR lines; and

- $177 million for everything else (primarily infrastructure access costs between other railroads and the National Network), FRA oversight costs, the Northeast Corridor Commission, and the State-Supported Route Commission.

Speaking of that state-supported route commission, Amtrak says they are partly to blame for higher federal subsidy payments for SSR trains: “By law, a standardized methodology governs how the full cost of serving ‘State-Supported’ routes is allocated to Amtrak and to those routes’ sponsoring partners. The IIJA required that this methodology be updated via a consensus-based process; as a result, proportional federal responsibility for operating costs in FY 24 (approximately 20%) was significantly higher than in previous years (approximately 13% in FY 19, just prior to COVID-19), and will remain elevated moving forward.”

New Operations presentation

Over a decade ago, Amtrak received two separate annual appropriations from Congress – one for railroad-wide operating subsidies, the other for railroad-wide capital expenses and debt service.

The FAST Act of 2015 changed that, instead ordering Amtrak to redo its accounting so there were two federal accounts, one for the Northeast Corridor and the other for all other routes (the National Network). The intent was to put an end to the practice of using Northeast Corridor operating profit to mask the operating losses of the other trains and instead plug that operating profit back into the bottomless pit of NEC capital needs.

(Ed. Plea for Help: If anybody reading this knows anyone at the Treasury Department’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service, please pass on the complaint to them that, almost a decade after the FAST Act changed the Amtrak account structure, the Monthly Treasury Statement still reports FRA outlays broken down into the pre-FAST Amtrak capital/debt account and “other.” So the latest May 2025 statement in Table 5 says, for year-to-date FRA outlays, Amtrak zero, “other” $3.128 billion. This kind of accounting breakdown is completely useless, and in the DOGE era, government agencies should not be out there perpetuating clearly useless behavior.)

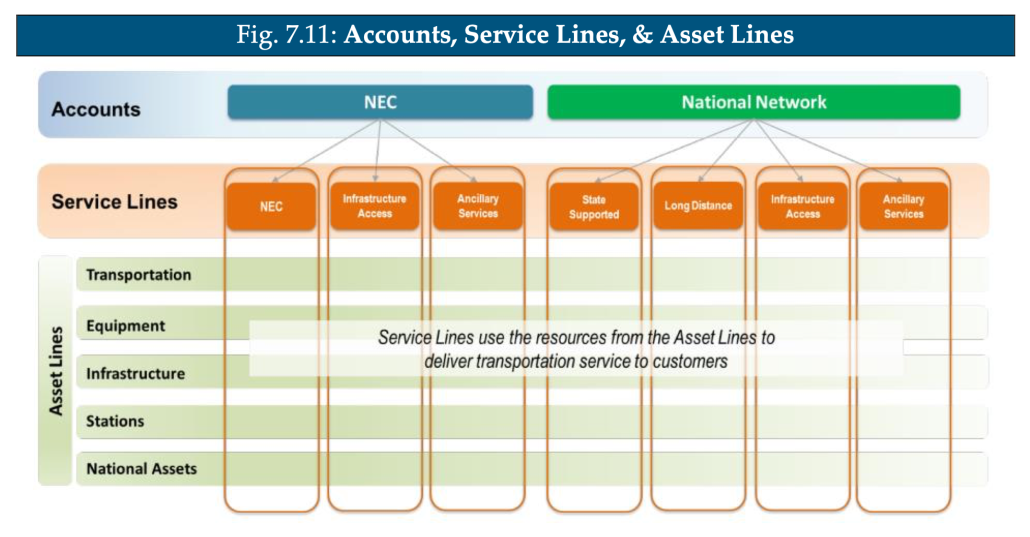

The FAST Act also mandated a second way of looking at Amtrak, by requiring the railroad to come up with five-year plans for each line of business. There are six of those (Northeast Corridor routes, State-Supported routes, Long Distance routes, Ancillary items, Real Estate and Commercial business, and “Infrastructure Access/Reimbursable” (mostly payments from commuter railroads to use Amtrak right-of-way on the NEC).

FAST also mandated a separate “Asset Line” breakdown, of which there are five: Transportation, Equipment, Infrastructure, Stations, and National Assets/Corporate Services. (Both the service lines and asset lines are fully defined on pages 134-137 of the FY26 budget request.)

Amtrak has a nice, though not particularly helpful, graphic:

So there were already two different ways of cross-cutting Amtrak’s FY 2026 appropriation request, in millions of dollars:

| By Service Line | NEC Account | NN Account | Total |

| Northeast Corridor | 462.1 | 462.1 | |

| State-Supported Routes | 596.6 | 596.6 | |

| Long-Distance Routes | 814.6 | 814.6 | |

| Infrastrucutre Access | 369.5 | 147.8 | 517.3 |

| Ancillary Services | 9.2 | 7.1 | 16.3 |

| DOT/FRA Takedowns | 9.3 | 10.9 | 20.1 |

| TOTAL REQUEST | 850.0 | 1,577.0 | 2,427.0 |

| By Asset Line | NEC Account | NN Account | Total |

| Transportation | 55.6 | 82.8 | 138.4 |

| Equipment | 105.3 | 755.2 | 860.5 |

| Infrastructure | 457.4 | 399.4 | 856.8 |

| Stations | 119.7 | 247.5 | 367.1 |

| National Assets/Corp. Serv. | 102.7 | 81.3 | 184.0 |

| DOT/FRA Takedowns | 9.3 | 10.9 | 20.1 |

| TOTAL REQUEST | 850.0 | 1,577.0 | 2,427.0 |

Then came the bipartisan IIJA infrastructure law in late 2021, which perpetuated Amtrak’s FAST Act accounting structure while turbocharging the capital side of the railroad with a guaranteed $22 billion in direct capital appropriations while also making Amtrak the likely recipient of most of an additional $24 billion in theoretically competitive Federal-State Partnership grants for upgrading passenger rail on the Amtrak-owned Northeast Corridor. (All of which is in addition to Amtrak’s regular annual appropriations.)

$46 billion in extra capital funding, while wonderful for the recipient, comes with costs. Amtrak explains the problem on page 133 of the request:

Historically, Amtrak has first and foremost been a company that operates trains; this remains the core of our mission. However, thanks to the unprecedented capital funding that Congress provided via the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), Amtrak has also become a major railroad construction company; today, we are leading, managing, or partnering on some of the biggest construction projects in the country.

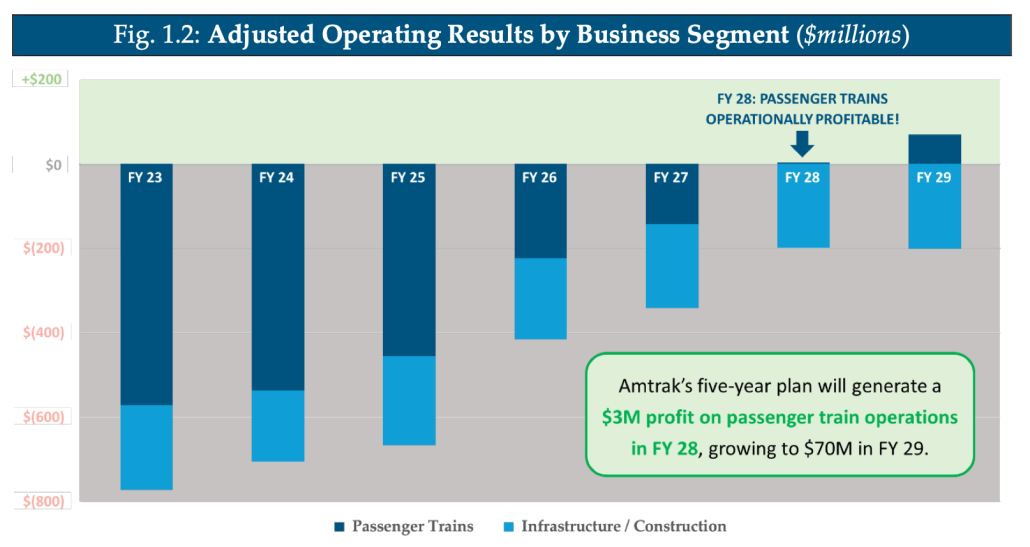

The growing scale of Amtrak’s capital delivery work has created a need for new, enhanced forms of financial analysis. Historically, Amtrak has reported its adjusted operating results on a consolidated basis. However, as many new project-related costs have to be considered “operating” rather than “capital” expenses under generally-accepted accounting principles (GAAP), those consolidated results no longer give the clearest possible picture of Amtrak’s performance as an operator of trains (or, for that matter, as a construction company).

(Things like project design and engineering apparently have to go into the operating budget, not the capital budget.)

This is a particularly political problem, because back in FY 2019, the Last Great Pre-COVID Year of rail ridership, Amtrak as a whole essentially broke even on an operational basis for the first time, a kind of Holy Grail moment for the railroad. Things obviously went the other way during COVID, but once ridership returned to pre-COVID levels, Amtrak’s five-year forecasts in last year’s budget never came close to operating balance, with a projected FY 2029 operating loss of $366 million.

So this year, the new presentation that splits up the train company from the construction company. Here is the old-style summary of operations in the FY 2026 plan, by service line, in millions of dollars:

| NEC | SSR | LDR | Access | Ancillary | TOTAL | |

| Operating Revenue | 1,689 | 939 | 695 | 313 | 457 | 4,093 |

| Operating Expenses | 1,240 | 1,170 | 1,258 | 468 | 372 | 4,509 |

| Oper. Profit/Loss | 448 | -231 | -563 | -155 | 85 | -416 |

Now here is how Amtrak splits that up in the new presentation:

| Train | Construction | ||

| Service | Business | Unified | |

| Operating Revenue | 3,456 | 638 | 4,093 |

| Operating Expenses | 3,353 | 1,156 | 4,509 |

| Infra. Access Transfer | -326 | 326 | 0 |

| Oper. Profit/Loss | -223 | -192 | -416 |

While both sides show a significant loss in FY 2026, Amtrak can now project the train service side of things to get back to break-even in just two more years (actually a $3 million profit, with a $70 million operating profit the following year), while the construction business continues to run at an operating loss of around $200 million per year (managing a gigantic capital program):

Operations – compare to airlines

Amtrak does actually report a metric used by non-rail passenger transport providers: cost and revenues per available seat-mile (ASM). Comparing the RASM and CASM numbers from the May 2025 Board of Directors meeting slide deck (for April 2025 stats) versus the average of the four major U.S. airlines RASM/CASM reporting in their first quarter 2025 earnings reports is interesting. Numbers in terms of cents per mile:

| cents per mile | RASM | CASM | Diff. |

| Amtrak Long Distance | 15.2 | 31.1 | -15.9 |

| Amtrak State-Supported | 17.2 | 22.9 | -5.7 |

| Big 4 Airline Average | 17.9 | 17.7 | 0.2 |

| Amtrak Northeast Corridor | 37.6 | 29.6 | 8.0 |

Ops and Cap together – the big picture

Operations are just one side of the budget, the other being capital. And in the IIJA era, capital is king. In the FY 2026 budget, Amtrak anticipates spending $8.6 billion on capital, versus just $4.5 billion on operational expenses.

| Amtrak Consolidated FY 2026 Budget, by Service Line (Million $$) | ||||||

| NEC | SSR | LDR | Access | Ancillary | TOTAL | |

| Operating Revenue | 1,688.6 | 939.5 | 695.3 | 312.9 | 456.5 | 4,092.8 |

| Operating Expenses | 1,240.4 | 1,170.4 | 1,258.5 | 468.1 | 371.6 | 4,508.9 |

| Oper. Profit/Loss | 448.2 | -230.9 | -563.2 | -155.2 | 85.0 | -416.1 |

| Regular Appropriations | 462.1 | 596.6 | 814.6 | 517.3 | 16.3 | 2,406.9 |

| IIJA Direct Appropriations | 835.2 | 1,320.4 | 988.7 | 155.3 | 6.5 | 3,306.2 |

| Other Appropriations | 855.7 | 185.0 | 192.6 | 1,286.6 | 0.0 | 2,519.8 |

| State/Other Rev. Sources | 288.9 | 181.9 | 86.8 | 643.7 | 0.8 | 1,201.9 |

| AVAILABLE FOR CAPITAL | 2,890.1 | 2,053.0 | 1,519.5 | 2,447.5 | 108.6 | 9,018.7 |

| Capital Expenses | 2,439.9 | 2,052.8 | 1,519.3 | 2,532.8 | 23.6 | 8,568.5 |

| Debt Repayment | 158.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 159.0 |

| CARRYOVER BALANCE | 291.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -85.0 | 85.0 | 291.5 |

Under this budget plan, Amtrak will spend just over half as much (53 percent) on operating expenses in 2026 as it will spend on capital. This is the sea change that the IIJA has wrought – back in 2019, the Great Pre-COVID Year, Amtrak’s operational spending was 208 percent of its total capital spending ($3.35 billion versus $1.61 billion).

The budget projects that ratio peaking this year and then capital spending gradually declining to $6.24 billion in FY 2030 as the IIJA trainset money spends out.

In terms of specifics in the combined (regular plus IIJA plus outside grant) capital program, the budget request has an excellent summary graphic of the big-ticket projects.

Other legislative requests

Once again, Amtrak is not only asking Congress for money, they also want a few other items from Congress this year:

- Treat federal appropriations as non-federal matching funds. The $36 billion IIJA grant program mentioned above, the Federal -State Partnership for Intercity Passenger Rail program, requires non-federal matching funds for its grants (see 49 U.S.C. §24911(f), which says that Amtrak “may use ticket and other revenues generated from its operations and other sources to satisfy the non-Federal share requirements” but not federal appropriations). Once again, Amtrak asks for appropriations bill language allowing their annual federal appropriations to be used as a non-federal match, despite that 24911(f) language. Congress has taken a dim view of this request in the past and is not expected to agree this year, either.

- Fix IIJA drafting error on Corridor ID program. Once again, Amtrak asks Congress to fix a drafting error in the IIJA. Amtrak makes a good case that the language in section 22101(h) of the IIJA was intended to allow Amtrak to spend up to 10 percent of its annual National Network appropriations under for the new Corridor ID program under 49 U.S.C. §22308 – but subsection (h) referenced 49 U.S.C. §22306 instead, which has nothing to do with Corridor ID. However, Congress has previously ignored this request, and at this point, we are not certain if a wholesale reexamination of the Corridor ID program would work in Amtrak’s favor. (Ed. commentary: In the recent Board slide deck, Amtrak bragged on their first three Corridor ID projects in the pipeline, and one of them was increasing service on the Sunset Limited from thrice-weekly to daily. This is the same Sunset Limited that is always the most money-losing route in Amtrak’s system on a per-passenger basis, with a FY 2024 operating loss of a gobsmacking 93 cents per passenger-mile (the next highest is 64 cents per mile on the Cardinal). The Sunset Limited currently loses $621 per passenger, so by all means, let’s do that seven times a week instead of three.)

- When transportation appropriations report language returns in FY 2026, Amtrak wants a “to the extent practicable” proviso added to their outsourcing ban, because they say a couple of items like modernizing Amtrak-licensed proprietary software may be impossible to do in the U.S.

- Homeland grant programs. Amtrak wants their annual FEMA Rail/OTR Bus Security Grant set-aside increased to $25 million (up from $10 million). They also want a new $25 million cybersecurity appropriation and a new one-time $26 million appropriation for increased security around the FIFA World Cup 2026.

ADA naming and shaming

The poor record of compliance with Americans with Disabilities Act requirements by Amtrak stations is well-known. A new December 2024 law requires Amtrak to come up with an action plan for ADA compliance, as well as a name-and-share status report on ADA compliance at all Amtrak stations, which starts on page 100 of the budget request. Amtrak says that the ADA applies at 521 of its stations, but is not responsible at all for ADA compliance at 143 of its stations and is only partly responsible at another 231 stations.

Amtrak says that of the 378 stations where they are partly or fully responsible for compliance, 137 are all the way there and the other 241 are on their way. For the rest of them, Amtrak wrote them each a letter to ask about ADA compliance specifics, and the list of who has responded and who has not starts on page 104 of the request. Some of the more prominent names that have not given Amtrak any specifics on ADA compliance status: the Maryland Transit Authority, Virginia Railway Express, Sound Transit, Metra, PennDOT, and SEPTA.

Food and beverage

As usual, Congress asked for, and Amtrak provided, an annual update on food and beverage service on long-distance trains, starting on page 126 of the budget request (with a mouth-watering French toast photo). Big news: the Crescent and the City of New Orleans both have full-service dining cars once again.

Train operations for FY24

Finally, it’s that moment you’ve been waiting for – the per-train operating profit/loss statistics for fiscal year 2024.

Once again, the two NEC trains and the Auto Train are the only ones priced appropriately to their cost. (Honorable mention to the Lincoln Service from Chicago to St. Louis, which came very close.) The population density of the NEC keeps mass ridership on the Northeast Regional, and the willingness of the downtown or inner suburb-dwelling ruling class to pay high fares for fast service (their time is money, after all) keeps the Acela very profitable. And the cost savings from not having to rent your own automobile for weeks or months while in Florida can make the high prices of the Auto Train a good deal.

Only the five busiest state-supported trains are shown in the table below; for all others, see the full table starting on page 72 of the budget request.

On the down side, the finances of the long-distance trains speak for themselves, especially the aforementioned Sunset Limited.