George W. Bush (2001 to 2009): The President Who Saved Amtrak

This article is a part of our series From Lighthouses to Electric Chargers: A Presidential Series on Transportation Innovations

This article is written solely in the author’s capacity as a former member of the Bush Administration and does not reflect the views of his current employer or any other employers since his service as Federal Railroad Administrator under George W. Bush.

George W. Bush was a great boss. I served as his Director of Transportation Policy when he was governor of Texas between 1995 and 2000 and then his Federal Railroad Administrator from 2001 to 2004.

One of my first meetings with him was in 1995, when he walked across the Capitol grounds to the old Insurance Building where most of his staff was housed. He came to my door and said, “transportation, huh? Allan, you remember the four things I ran on last year?” Like most Texans, I had seen the ads frequently enough to remember that he ran on tort reform, welfare reform, changing the juvenile justice system, and improving education. (See C-SPAN video of his October 27, 1994 campaign rally.)

The governor said to me, “Your job as my transportation guy is to not do anything so stupid that it gets in the way of us achieving my four goals.” I could see the Venn diagram and assured him that I would not interfere with his goals, which were in fact achievements of his first legislative session.

Governor Bush built a remarkably cohesive senior staff; unlike other governors whose staff either had their own agendas or were concerned about their access to the Boss, Bush’s senior staff were solely focused on how to help the governor (and the entire office) succeed. Whenever I met with him directly, he always started the meeting right on time, he asked the one or two toughest questions about whatever you had briefed him on (which meant that he read and understood your memos), he asked for your input and recommendation, and he always ended with a clear outcome and decision.

In 2000, Governor Bush defeated Vice President Al Gore in one of the closest races in presidential history. Although Gore won the popular vote, Bush won 271 electoral votes, just one more than required to win. The vote was not settled until the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 5 to 4 decision, ended a Florida recount vote on December 12.

September 11

By most any standard, the most consequential transportation event of President George W. Bush’s two terms happened during his first year in office. Not only were commercial aircraft used as weapons by terrorists killing more than 3,000 in New York City, Washington DC and southwestern Pennsylvania, but Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta grounded every plane in US airspace that day, all 4,546 of them. I can’t tell you about that story because I was 700 miles away.

I was in Chicago for a morning meeting on highway-rail grade crossing safety, barely six weeks after being confirmed as administrator of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA). The night before, I attended a game at Wrigley Field in the company of railroad labor leaders. In my room at the Palmer House Hilton, my deputy administrator, Betty Monro, called my room phone and told me to turn on the morning news. There, we watched loops of video of an airliner crashing into the side of one of the World Trade Center towers. Later, gathered at Metra headquarters with FRA colleagues and Chicago rail leaders, we watched in horror and stunned silence as the second tower collapsed in a cloud of smoke and ash.

Our regional office gave us the keys to one of their minivans, and we listened on the car radio for any news or updates. By early evening, we made it back to Washington, D.C. and drove past the smoldering wreckage of the Pentagon.

(Ed. Note: For more information on the immediate 9/11 response: see Secretary Mineta’s oral history interview).

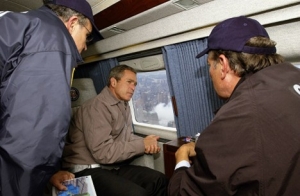

President Bush over the World Trade Center disaster site with New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani (left) and New York Governor George Pataki (right) on September 14, 2001. Source: White House Photo Office.

Amtrak About to Go Bankrupt

My biggest challenge during my three-year tenure as administrator was during the summer of 2002 when the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) was about to go bankrupt. I worked alongside Secretary Mineta in convincing the president and White House staff to permit me to issue a $100 million loan to keep that from happening.

Five years earlier, Congress had passed the Amtrak Reform and Accountability Act of 1997. That law committed Amtrak to wean itself from federal operating subsidies by December 2002, a goal that built on a previous commitment by the Amtrak Board and the USDOT to take actions along a “glidepath” to operating self-sufficiency.

The factors that led to Amtrak’s inability to achieve this self-sufficiency goal are numerous and complicated—a comprehensive report by the Congressional Budget Office report issued in September 2003, “The Past and Future of U.S. Passenger Rail Service” is an excellent primer on intercity passenger rail policy and on Amtrak’s perpetual financial problems.

While statutory provisions in the 1997 law relaxed some labor protections and made it easier to reduce some of train routes, the underlying politics of intercity passenger rail were not substantially altered — influential rail labor unions and elected officials who supported its intercity passenger rail routes made it hard for the railroad to shed services. Instead, Amtrak increased its debts to replace and upgrade rolling stock, and purchased new higher-speed trains that would serve the Northeast Corridor. (In 1999, Amtrak unveiled its plans for Acela service).

After I moved to D.C. in April 2001 to work as a transportation staff member in the Office of the Secretary while awaiting my Senate confirmation, I attended my first meeting with Secretary Mineta and Amtrak CEO George Warrington. In that meeting, Warrington requested approval by the Secretary to allow Amtrak to mortgage NYC’s Penn Station to secure a $300 million loan to offset the railroad’s operating expenses (the USDOT held interests in the Penn Station Corporation that had to be subordinated to allow the station’s mortgage). The Secretary had a seat on the Amtrak Board of Directors, but this was our first warning that Amtrak was on much less stable financial footing than its leaders were telling the public. We learned the railroad was unlikely to meet its 2002 self-sufficiency deadline.

Amtrak’s finances grew more dire as 2002 arrived. Almost all of its capital assets had been leveraged for debt that increased $2.7 billion between 1997 and 2001, resulting in $250 million in annual interest payments by 2003, up from $74 million in 1997. Amtrak’s financial position (high debt load, expenses exceeding revenues) was sufficiently compromised to keep them from receiving a clean third-party audit which led to short-term private credit drying up.

Warrington subsequently resigned and was replaced by long-time railroader David Gunn in May 2002. Gunn determined that the railroad’s financial problems would effectively exhaust its federal operating support and the railroad would have to shut down before the July 4th holiday unless additional federal resources were made available.

Contemplating Amtrak’s possible demise, I believed that the political ramifications of shutting down its services were disproportionately larger than its average annual federal subsidy of $1 billion. Amtrak had routes in 46 states, serving about 23 million annual passengers.

Amtrak’s Route Map as of 2002. Source: U.S. General Accountability Office.

Our team at the FRA worked with others in the USDOT to catalog the consequences of a possible Amtrak shutdown. At the time, 90% of Amtrak’s roughly 22,000 employees were members of various rail unions and would qualify for multiple years of job separation payments if their jobs were eliminated in a shutdown. We calculated that the overall cost of those payments at about $3.2 billion. This meant that if Amtrak were to stop running trains, its total taxpayer cost would be equivalent to more than three years of added cost. Amtrak’s employees also paid more than $400 million annually into the Railroad Retirement System and without those employee contributions, payroll taxes from freight rail employees and the railroads would have to increase.

Amtrak’s ownership and management of the Northeast Corridor (NEC) rail assets also had implications for other users of the railroad. The corridor was used by New Jersey Transit and the Long Island Rail Road, something of great importance to Republican New York Governor George Pataki and former Republican New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman (who then served as President Bush’s EPA Administrator.) Moreover, certain freight railroad services depended on a solvent Amtrak to maintain its tracks.

In the spring of 2002, I met with the president at the White House, along with Secretary Mineta, Deputy Secretary Michael Jackson, and members of the Domestic Policy Council and Office of Management and Budget. We discussed whether to extend Amtrak a loan or let it shut down.

At one point, President Bush told the assembled group that I had been with him in Texas, “and my highway guy rode the bus!” (Sure enough, my family only owned one car, and I took the No. 5 bus from North Austin to a stop in front of the Texas Capitol.) He then sighed and told me, “Rutter, you’re killing me with this Amtrak stuff.”

I knew that he implied the word “again” in that statement. When I was his transportation policy director back in Austin, he had signed legislation that authorized Texas DOT to provide a $5.6 million loan to Amtrak that prevented the elimination of Amtrak’s Texas Eagle long-distance service, which ran from San Antonio to Chicago.

Ultimately, the President agreed with my recommendation that shutting Amtrak down was not a good idea. Although Governor Pataki may have been more persuasive than I was in reaching that decision.

While Gunn had requested a $200 million loan guarantee from the FRA, we instead executed a Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing program (RRIF) loan of $100 million on June 28, 2002 (the second of my FRA tenure) which was followed in short order by a supplemental Congressional appropriation of $205 million to keep Amtrak afloat the remainder of the 2002 fiscal year.

The RRIF loan was also significant in that it allowed us to include loan conditions that required additional reporting by Amtrak to the FRA on route-level revenues and expenses and more details on budgeted and actual capital expenditures, among other items. That began a practice included in future Amtrak appropriations that extended these additional reporting requirements for USDOT to serve its duty as a fiduciary of federal funding support.

Amtrak has since achieved more stable capital and operating funding and less drama. Much of that progress would not have been possible without a solvent passenger rail entity and I was honored to have been given the privilege of serving both President Bush and Secretary Mineta, and play a small part in preserving intercity passenger rail.

Allan Rutter is a senior research scientist and freight analysis program manager at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute. He served as Federal Railroad Administrator under President George W. Bush from 2001 to 2004. As a Senior Associate with Cambridge Systematics, he led or participated in state rail plans in eight states, including California and Texas. Mr. Rutter previously served as chief executive of the North Texas Tollway Authority and also worked for four different Texas Governors in various capacities.

The views above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Eno Center for Transportation.