By So Jung Kim and Robert Puentes

Transportation network companies (TNCs)—Uber, Lyft, and Via—are now established parts of many cities’ urban mobility systems. Given their popularity, they are also attractive targets for state and local policymakers looking for a way to fund transit and infrastructure, to establish parity with taxis, to cover regulatory costs, and to support programs that improve equitable mobility.

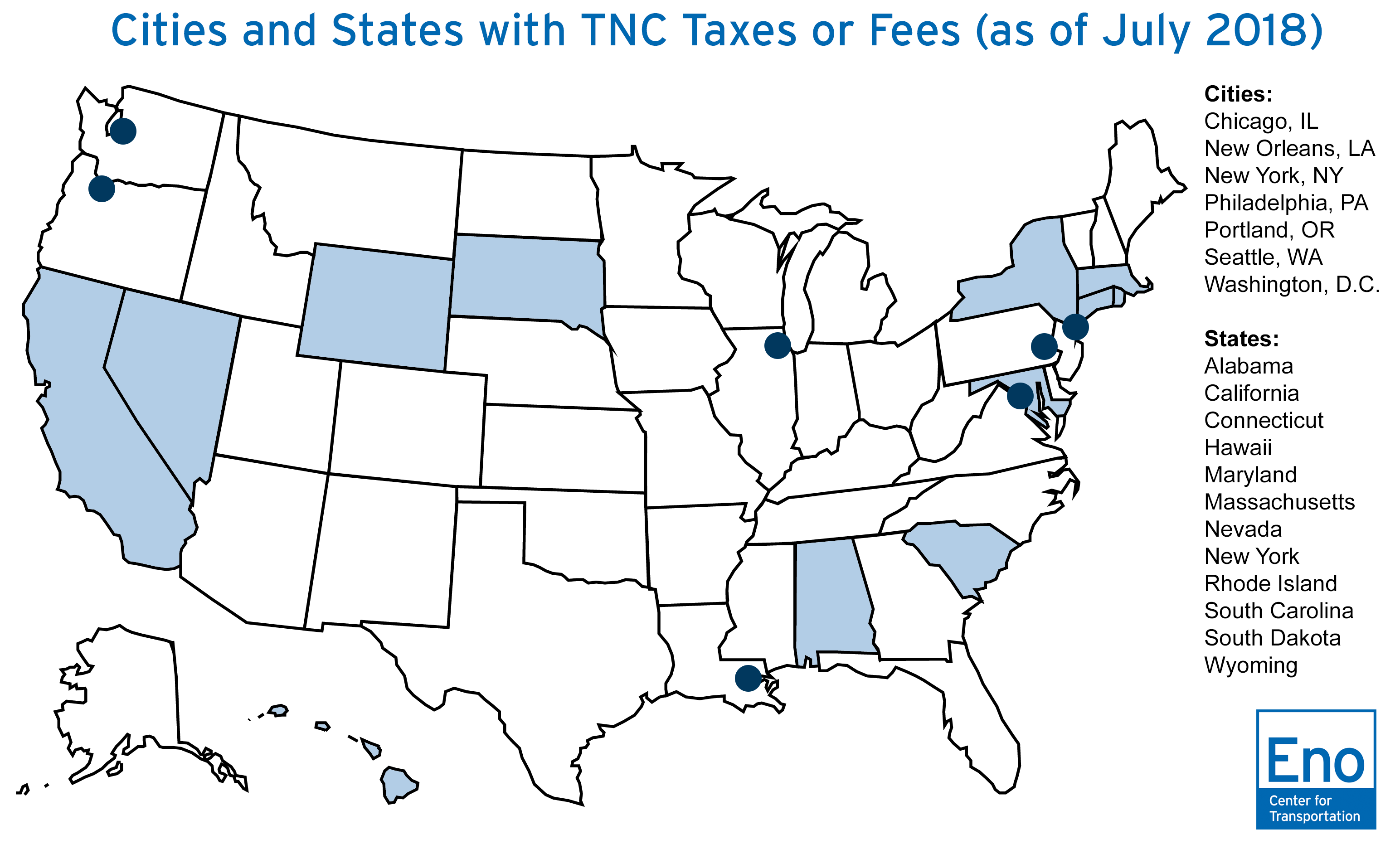

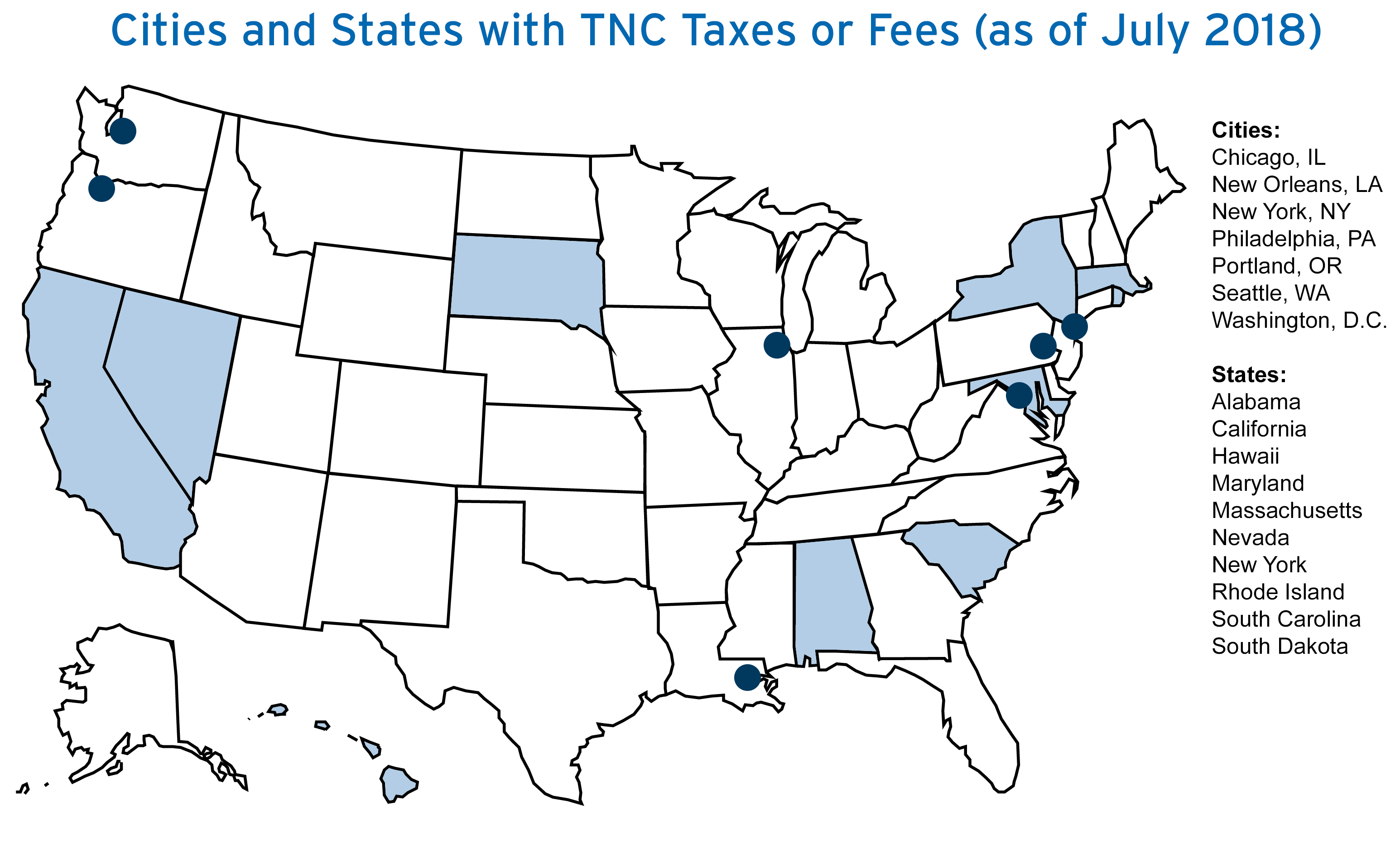

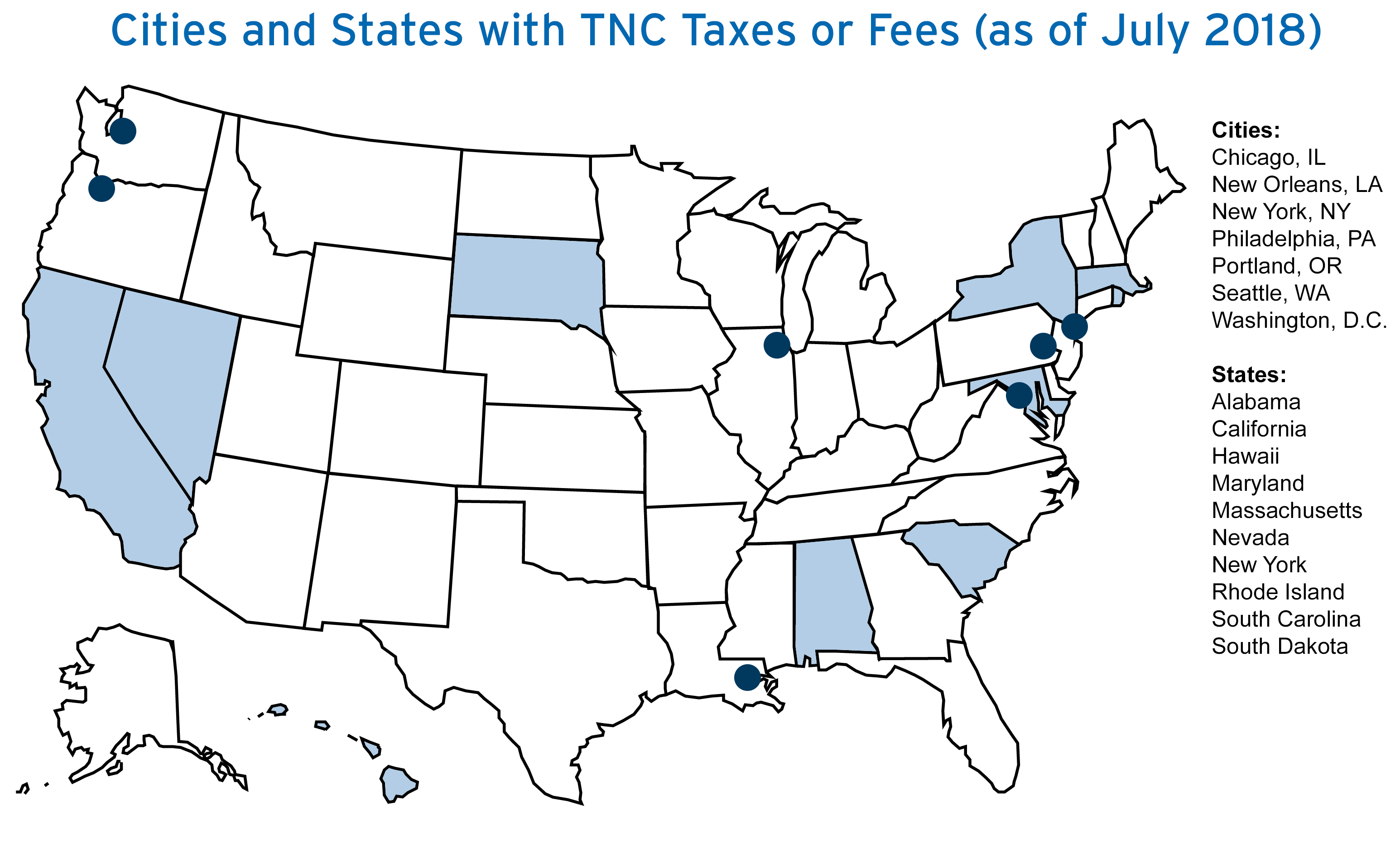

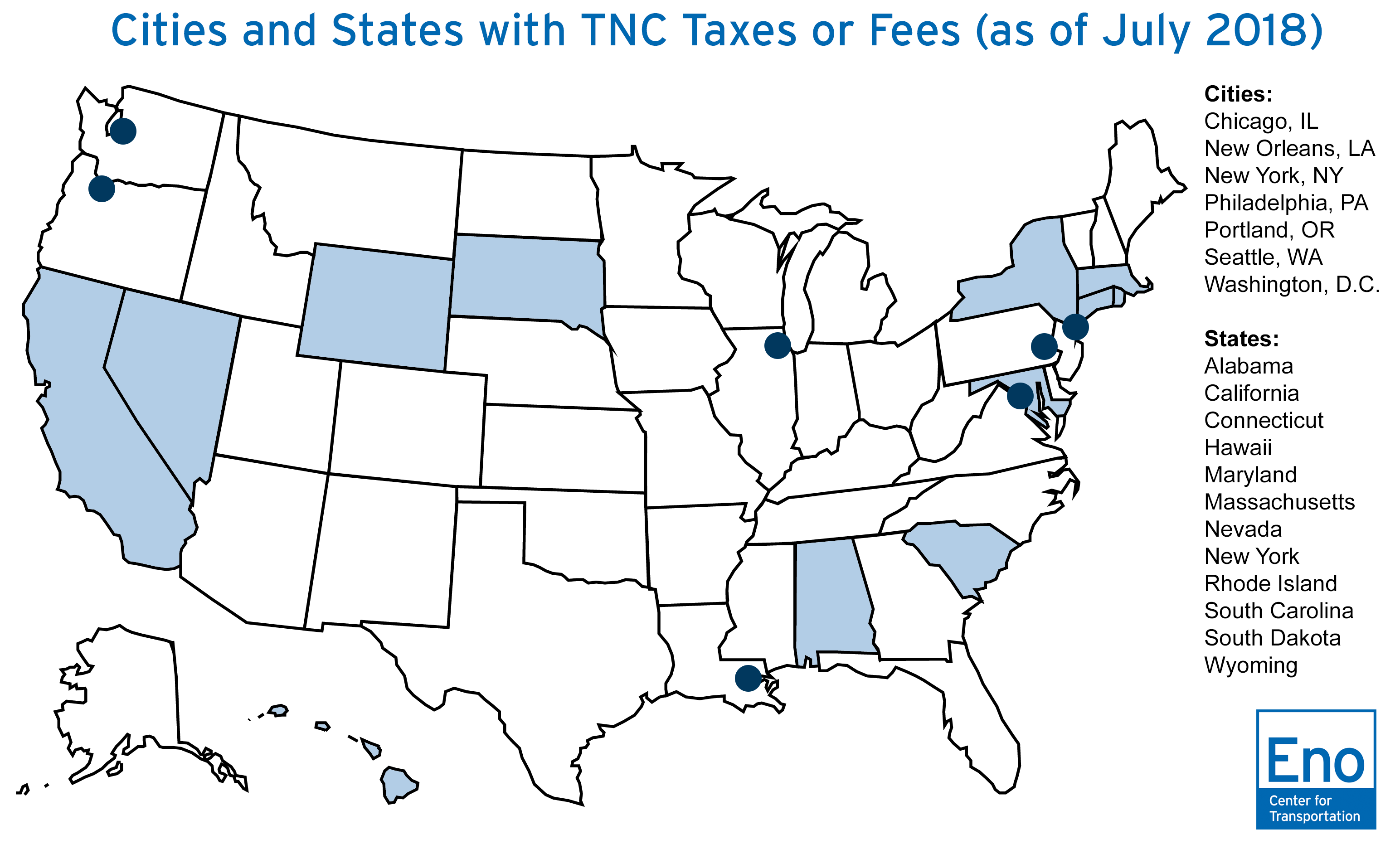

Today, seven major cities and 12 states have some type of fee or tax on TNC trips. While it may be a straightforward way to raise revenue, these charges are often shortsighted budget exercises rather than deliberate public policy. As more states and cities consider taxes on TNC services, policymakers should be cautious and thoughtful about how their decisions affect transportation behavior.

Unfortunately, too little is known about TNC fees. This uncertainty has pitted transit and new mobility advocates against each other in an unhelpful debate that has hindered new kinds of shared-service partnerships and collaborative thinking about the best way to get around increasingly congested places. As services like TNCs proliferate around the globe, it is important to understand what these fees are, what purpose they intend to serve, and how they fit into broader metropolitan transportation policies.

The table below shows the current state and general purposes of TNC taxes and fees to date in the United States.

| Location |

TNC Tax/Fee |

When Enacted or Implemented |

Disposition of Funds |

| Cities |

Chicago, IL |

$0.67 per trip |

January 2018 |

$0.02 to Business Affairs and Consumer Protection

$0.10 to vehicle accessibility fund

$0.55 to city general fund |

| New Orleans, LA |

$0.50 per trip originating inside the parish |

April 2015 |

100% to Department of Safety and Permits |

| New York, NY |

8.875% of total fare |

2014 |

51% to city general fund

45% to state general fund

4% to Metropolitan Transportation Authority |

| $2.75 per trip or $0.75 per rider if pooled |

January 2019 |

100% to Metropolitan Transportation Authority |

| Philadelphia, PA |

1.4% of total fare of trips originating inside the city |

November 2016 |

By Pennsylvania state law:

66.67% to city public schools

33.33% to city parking authority |

| Portland, OR |

$0.50 per trip |

December 2015 |

100% to Bureau of Transportation |

| Seattle, WA |

$0.24 per trip on rides originating inside the city |

July 2014 |

$0.14 to Department of Finance and Administrative Services

$0.10 to Wheelchair Accessible Services Fund |

| Washington, D.C. |

6% of total fare |

October 2018 |

17% to Department of For-Hire Vehicles

83% to Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority |

| States |

Alabama |

1% of total fare |

February 2018 |

50% to Public Service Commission regulator

50% to trip-originating cities and counties |

| California |

0.33% of total TNC revenue |

September 2013 |

100% to California Public Utilities Commission Transportation Reimbursement Account |

| Connecticut |

$0.25 per trip |

January 2018 |

General fund |

| Hawaii |

4% of total fare |

January 2018 |

General fund |

| Maryland |

State law allows individual counties and municipalities to impose their own per-trip assessments up to $0.25 |

July 2015 |

100% to State Transportation Network Assessment Fund

Cities assessing maximum $0.25: Ocean City, Annapolis, Frederick, Brunswick, Baltimore

Counties assessing maximum $0.25: Montgomery, Prince George’s |

| Massachusetts |

$0.20 per trip |

August 2016 |

50% to trip-originating cities infrastructure

25% to taxi industry assistance

25% to Commonwealth Transportation Fund |

| Nevada |

3% of total fare |

May 2015 |

100% to State Highway Fund up to $5 million in a two-year period, then deposits into State General Fund |

| New York |

4% of total fare on trips originating outside NYC |

June 2017 |

100% to state general fund |

| 2.5% of total fare |

2014 |

100% to Black Car Fund workers’ compensation insurance |

| Rhode Island |

7% of total fare |

July 2016 |

General fund |

| South Carolina |

1% assessment on total fare |

June 2015 |

1% to Office of Regulatory Staff

99% to State Treasury Trust and Agency Fund |

| South Dakota |

4.5% of total fare |

October 2017 |

General fund |

| Wyoming |

4% of total fare |

March 2017 |

69% to state general fund

31% to local governments |

Earlier this spring, the state of New York levied new surcharges on TNC and taxi trips in the busiest areas of Manhattan, while in Washington State, efforts to apply the taxi sales tax to TNCs failed. Georgia lawmakers proposed a TNC-trip fee as part of a regional transit bill. Philadelphia officials called for switching its per-trip percentage assessment to a $0.50 surcharge in order to generate more revenue.

Earlier this spring, the state of New York levied new surcharges on TNC and taxi trips in the busiest areas of Manhattan, while in Washington State, efforts to apply the taxi sales tax to TNCs failed. Georgia lawmakers proposed a TNC-trip fee as part of a regional transit bill. Philadelphia officials called for switching its per-trip percentage assessment to a $0.50 surcharge in order to generate more revenue.

Policy Questions

There are four main questions cities and states are trying to answer when they levy taxes and fees on TNCs. Some reflect a rational nexus between the fee charged and the needs created and benefits incurred by the service. But that is not always the case.

Can TNC taxes and fees offset negative effects of urban congestion?

TNCs are criticized for exacerbating congestion, particularly in busy downtown areas where they are routinely used for work trips. Despite the growing presence of TNCs on the streets, the vast majority of U.S. commutes are in privately owned, single-occupant vehicles (SOVs). Yet, no major city specifically taxes SOVs for their disproportionate impact.

TNCs generally support taxes on their services as long as they are part of broader transportation initiatives. They have lobbied in support of congestion pricing, fuel tax indexing, toll increases, and ride-pooling incentives across the country. For example, TNCs backed Governor Andrew Cuomo’s congestion pricing scheme for New York City, but opposedthe final outcome of surcharges only on TNCs and taxis, sparing all other SOV and truck drivers entering super-crowded, lower Manhattan.

Should TNC taxes and fees fund infrastructure and public transit investment?

Several states deposit tax revenue into generalized state transportation funds for infrastructure. Of those states, a subset, including Maryland, South Carolina, and Massachusetts, return portions of the assessments to each municipality or county where the trip originated, where they are likely to be spent improving local roadways. In a few cities, leaders are wielding TNC fees as a way to both take advantage of growing TNC competition and to prop up the budgets of their public transit authorities, partly to offset ridership losses.

However, the revenues raised from TNC fees are very small compared to transit agency budgets. Chicago‘s new 15-cent fee increase is dedicated to the regional transportation network and will raise an expected $16 million this year in order to support the agency’s $2 billion annual operating budget. The District of Columbia’s2019 Budget Support Act raised the TNC per-ride tax to 6 percent, up from 1 percent, in order to raise an estimated $18 million for its regional transit system’s $1.8 billion annual operating budget.

Local D.C. officials justified this escalation saying TNCs are direct competitors diverting local ridership and revenue away from subway trains and buses. In response to these assertions, TNCs point to research indicating their efficacy as first-mile, last-mile and late-night complements that encourage transit use. Six District of Columbia council members recently introduced legislation to reduce the pooled ride tax back to 1 percent, which would help to encourage sharing of rides.

Can TNC taxes and fees provide parity with traditional taxi services?

Taxes on traditional taxi services predate the advent of TNCs. Eight states apply their general sales taxes to taxi trips. Seattle, Washington, D.C., and New York City have per-trip taxi fees that augment local budgets. Hawaii, South Dakota, and Rhode Island clarified through state law and agency guidance that TNCs are indeed subject to an equal sales tax rate as taxis there. Portland, Oregon levies an equal $0.50-fee on both service providers’ rides. Deregulation is another path of equivalence: New Jersey repealed state sales taxes on limousine services effective May 1, 2017 so both TNCs and limousines could compete without extra taxes.

Blanket application of service sales taxes and taxi fees on TNCs make competition for single riders seem fairer, but it could cause unintended consequences. One newer feature of TNC services in major urban hubs is ride pooling: two or more people who happen to be traveling in the same direction can share a trip (UberPOOL, Lyft Line, and Via). With a theoretically unlimited chain of passengers entering and exiting throughout a pooled mega-route, a taxi-like per trip fee added to each rider’s bill could tax a shared-use vehicle many times over—discouraging a travel option that has potential benefits for reducing congestion and mitigating environmental impact. Flat fees, such as Chicago’s 67 cents per ride, amount to a regressive tax on the lower cost rides, especially those that are shared rides. For example, a 67 cent fee on a $4 shared ride amounts to an 18 percent tax.

Another key difference between TNCs and taxis is how prices are calculated. TNCs are unique for their app-based, on-demand variable pricing, in stark contrast to strict taxi fares charts decided by the local government. A percent-based sales tax on top of TNC-trip surge pricing, after a major sporting event for example, could balloon into a very large amount that costs much more than a similar trip in a traditional taxi charging a constant rate—to the latter’s competitive advantage.

Should TNC taxes and fees create funding streams for regulatory costs and community needs?

Without a doubt, regulation costs money and time, especially when the target industry is constantly innovating. Our analysis shows that frequently, revenues go directly toward the operating, administrative, and enforcement costs of regulating the new TNC industry. Governments’ first priority and least politically fraught role in regulating modern transportation is safety, as noted by the prevalence of TNC laws regulating and licensing vehicles and drivers. Thus, collecting funds for the cost of inspections, registrations, and permits makes perfect sense.

Policymakers can use modest fees to ensure everyone in the region benefits from TNC services. Chicago and Seattle each set aside a dime from each TNC fee for improved wheelchair accessibility services in for-hire vehicles like taxis. However, TNC drivers are often excluded because regulations make them ineligible for the funds. Portland is considering shifting its surplus revenue toward the needs of passengers with disabilities. From 2016 to 2021, a nickel of Massachusetts’ $0.20 per-trip fee funds programs to assist the traditional taxi and livery small businesses to retool in the face of modernizing technology. Philadelphia spends two-thirds of its fee on city public schools, a non-transportation-related, public beneficiary of city spending.

Moving Forward

For now and the near future, cities and states will continue to experiment with a range of rules and regulations as they navigate a rapidly changing mobility landscape. As they do so, they must balance the temptation to quickly raise revenue with the long-term public policy goals they are ultimately trying to achieve.

If policymakers are fixated on reducing congestion, they should focus on actions that reduce SOVs—regardless of whether that trip is in a personal or TNC vehicle. Providing exemptions or lower prices for shared rides, charging flat fees on all SOVs, or some combination of these kinds of policy levers would certainly help tackle congestion in a more meaningful way than narrowly targeted TNC fees alone.

If the goal is to generate revenue for transit agencies, per-trip TNC fees are likely not sufficient replacements for the yawning budget gaps they are facing. The desire to support metropolitan public transit is certainly a worthy one. But the relationship between TNCs and transit appears to be more symbiotic than antagonistic. The very existence of TNCs allows at least a portion of urban residents to live without owning personal cars and to therefore be more reliant on transit. Greater availability of transportation options is a net positive that helps citizens to better access jobs, meet their individual needs and desires, and reach further economic opportunity.

At their best, TNCs enhance mobility and provide access for all community members. Despite robust activity within federalist laboratories of policy, the broader debate is currently fixated on taxation and deems TNCs as special exceptions to the norm. Instead, policymakers might be better served viewing them as now-established presences that should be better integrated into holistic transportation networks and missions.