This week, the Washington DC-area mass transit provider, WMATA, formally sounded the alarm on its own version of the “fiscal cliff” facing most major transit systems as federal COVID aid finally runs out without transit ridership returning to its pre-COVID levels. WMATA management said that they will be forced into massive service reductions starting on July 1, 2024, probably leading to a “death spiral,” unless significant new funding is provided.

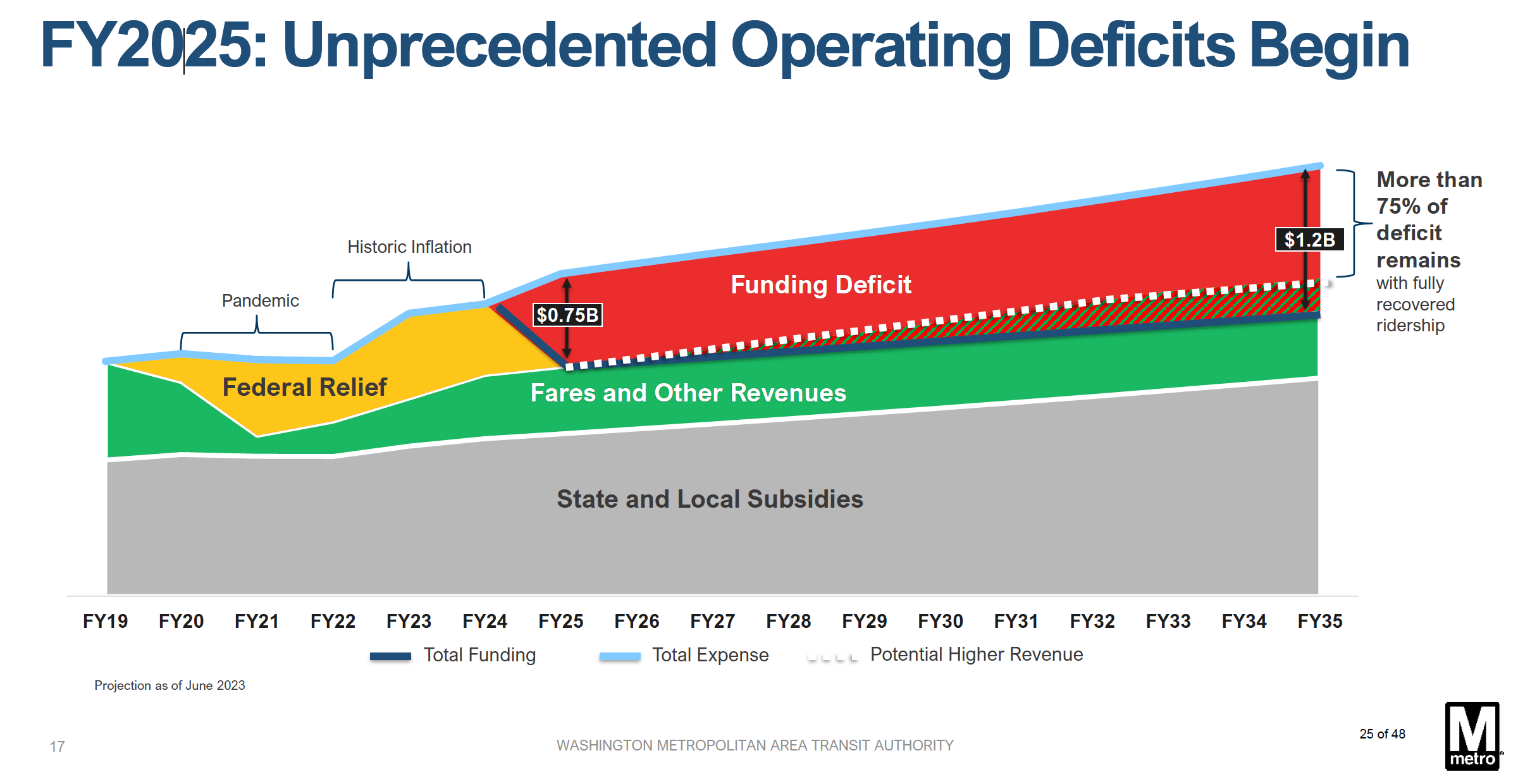

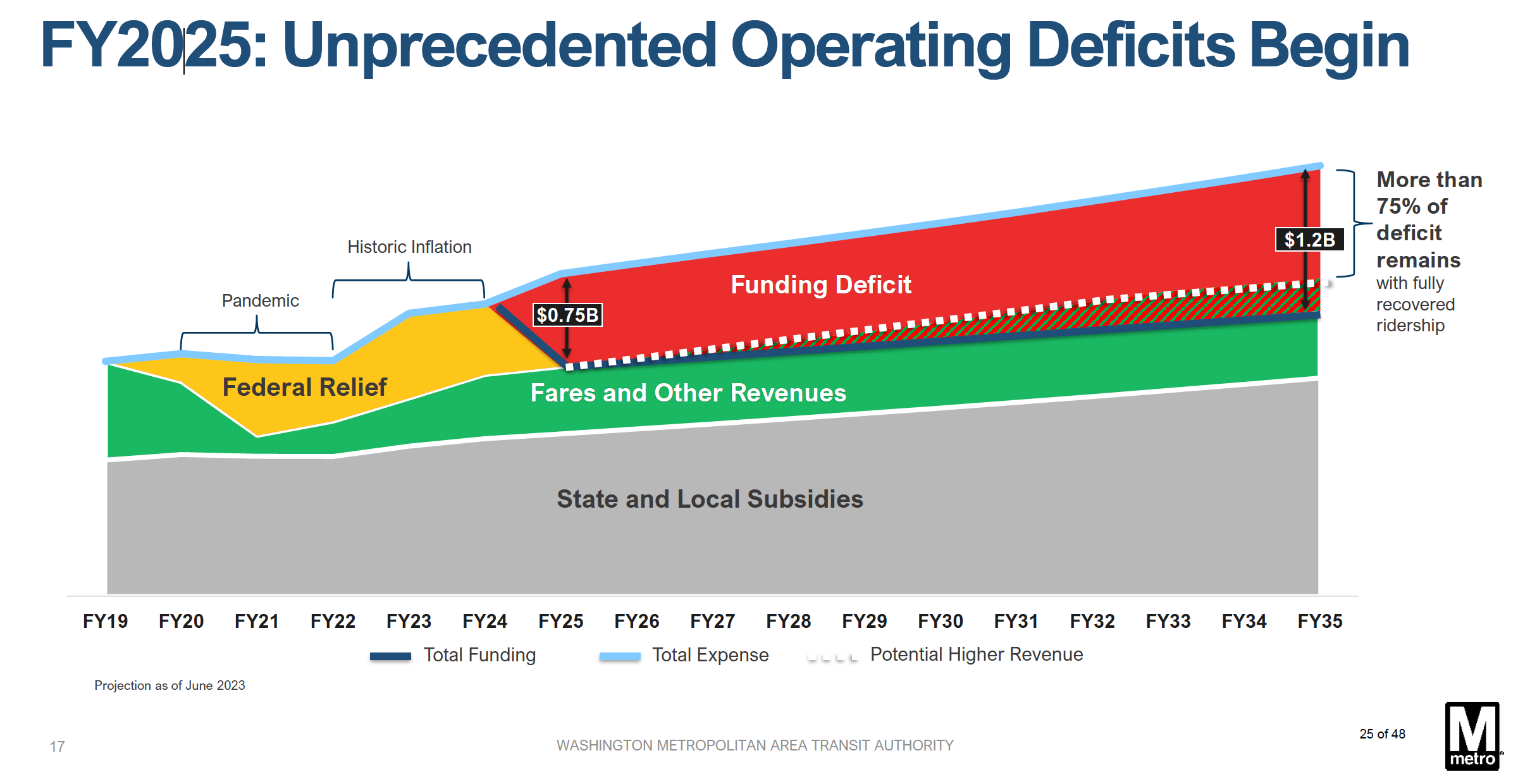

In a presentation to the Finance Committee of its Board of Directors, WMATA management said “Following the exhaustion of federal relief funding in FY2024, Metro expects an operating deficit of $750 million in FY2025. This is more than a one-year challenge. The deficit is projected to continue its growth through FY2035 even with continued ridership recovery.”

Some, but by no means all, of the financial problems facing WMATA are shared with other transit agencies around the country. But some are unique to WMATA. The presentation breaks down the causes of next year’s $750 million projected deficit into three:

- Decreased post-COVID revenue: $288 million. Ridership is still at 75 percent of pre-COVID levels, which affects not only farebox revenues but also parking and advertising revenues. This problem is shared by other transit providers across the land.

- Inflation and collective bargaining agreements: $266 million. Not only has everything that WMATA purchases gone up substantially in price, but their labor contracts have automatic escalator clauses built in that tie annual wage increases to inflation. Again, this is a problem shared by other transit providers.

- “Jurisdiction subsidy credit”: $196 million. This one is unique to WMATA, which gets over half its operating revenues every year from annual appropriations made by state and local governments in Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia. Apparently, at the start of the pandemic, when municipal governments were dreading a tax base collapse (which wound up not happening), WMATA offered to help out by reducing the amount of operating subsidies to which they were entitled and to forego the three percent annual subsidy increase from a 2018 agreement.

WMATA management says this deficit is now systemic, and includes a slide projecting that, even if ridership recovers completely to pre-COVID levels, there will still be a deficit of around $900 million ten years from now.

A $750 million deficit next year would be 29 percent of Metro’s estimated total operating budget, which they say is too large to be closed by cost cutting and fare increases.There follows a series of slides in the deck showing the real-world effects of the Doomsday Budget that WMATA will have to adopt next year if no new money comes in from outside.

WMATA says that they would need to cut expenses by 37 percent (-$947 million), which they estimate would also cut revenue by 37 percent (taking $197 million away from the savings provided by the service cuts) to fill that $750 million gap, and that once you cover the fixed costs, the service cut necessary to get a 37 percent drop in expenses translates to a gobsmacking 67 percent reduction in service.

On the rail side, that would mean going from 124 trains in service to 52 trains, minimum gaps of at least 20 minutes between trains all day, and closing at 9:30 p.m. On the bus side, this would mean going from 135 bus routes to just 37, with the same 20+ minute minimum wait times and 9:30 p.m. system shutoff. On both rail and bus, the remaining vehicles would be incredibly crowded and uncomfortable.

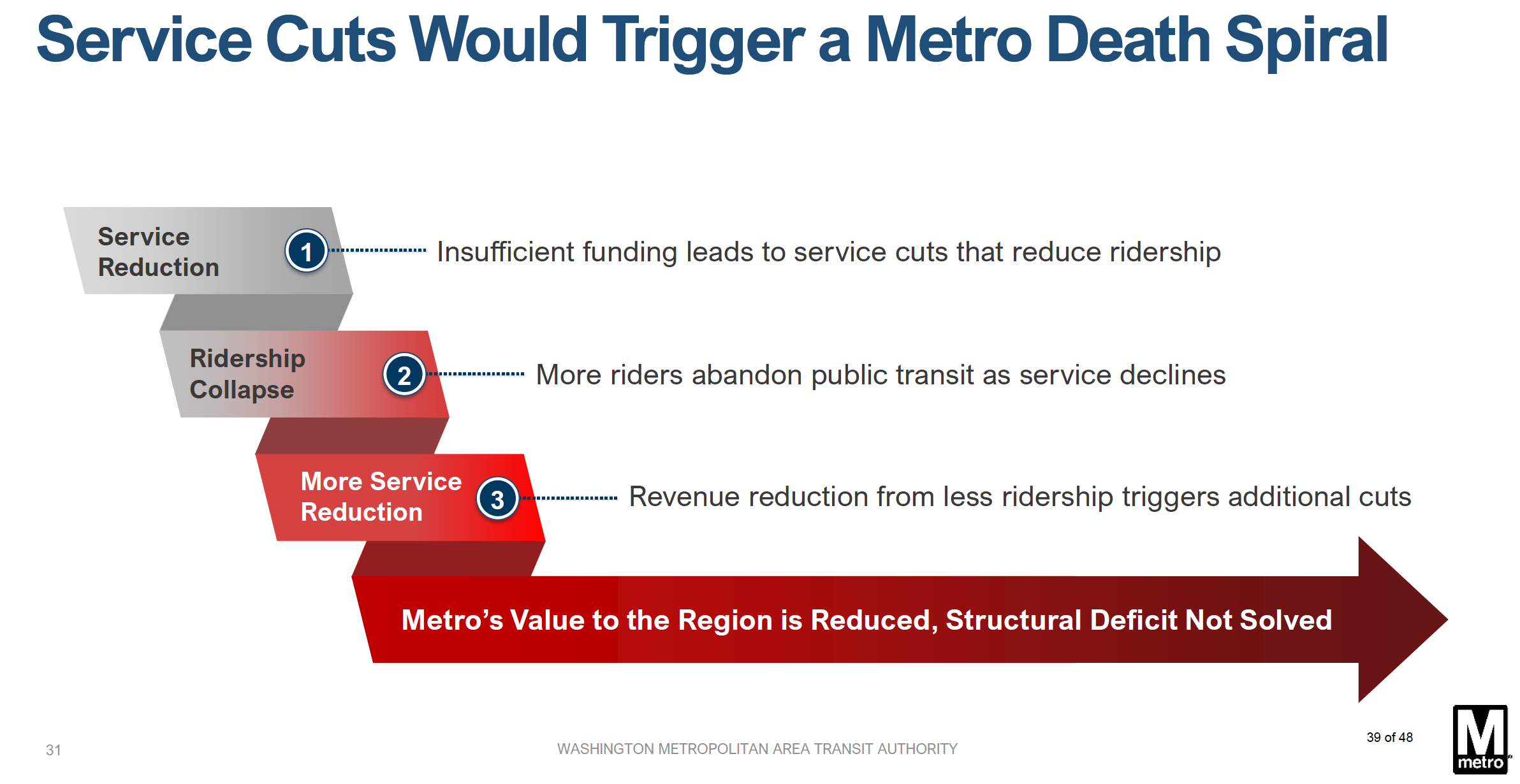

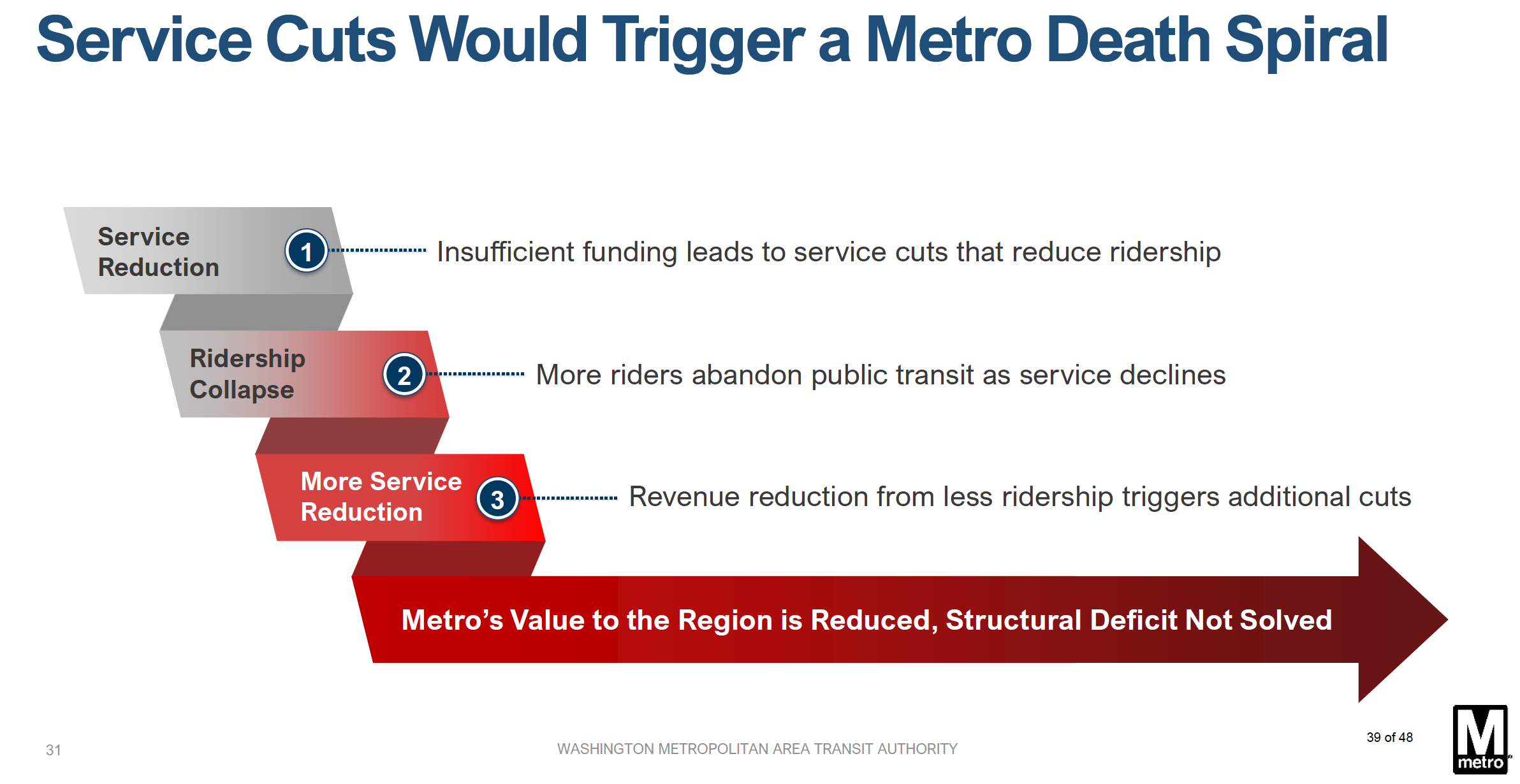

WMATA admits that this level of service cut would probably lead to the fabled “death spiral,” where bad service drives away customers, leading to reduced revenues, which leads to even worse service, ad infinitum to the bottom. What’s more, they actually attempted to produce a graphical representation of a death spiral, which the Eno policy team quite liked:

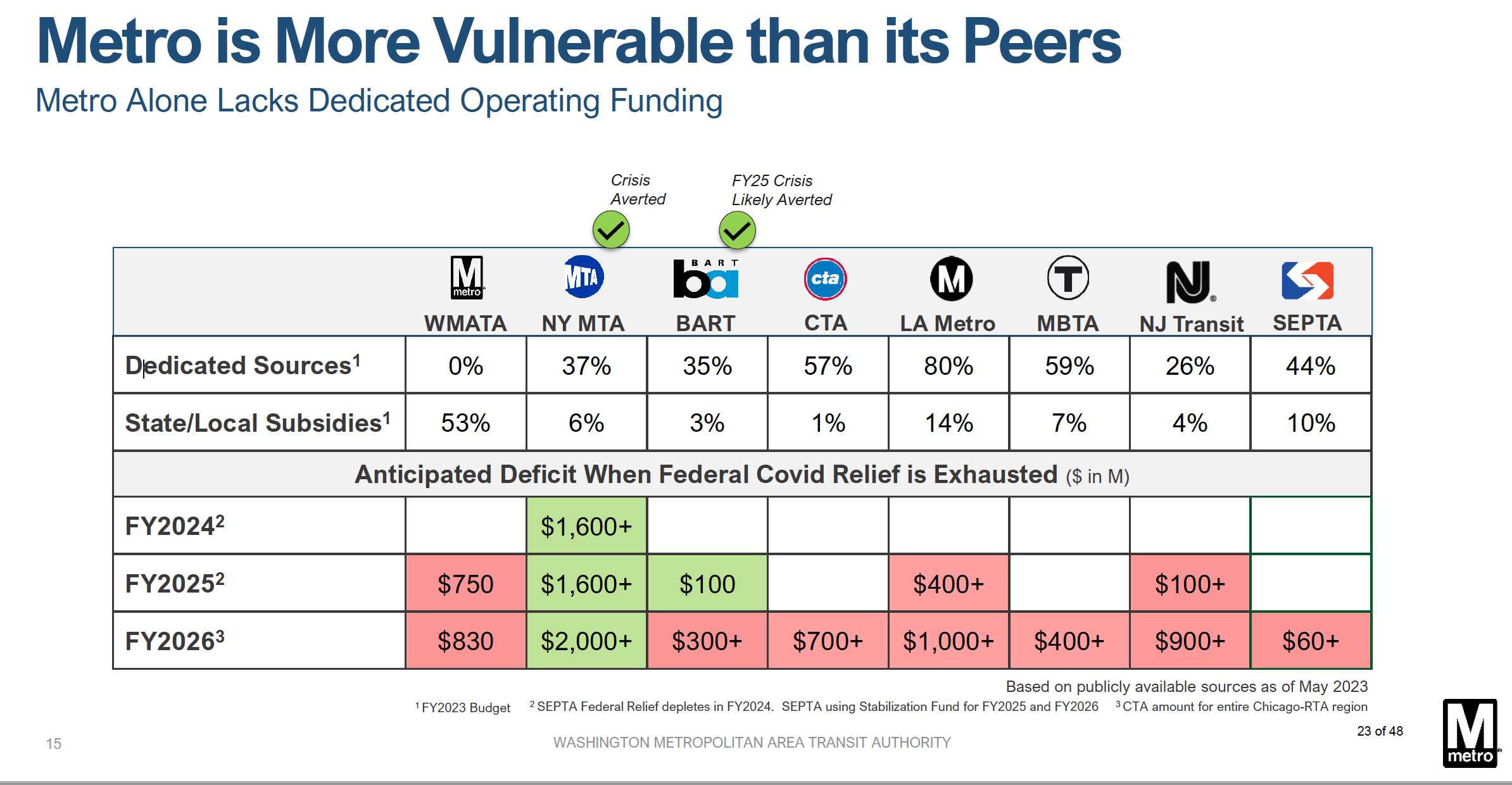

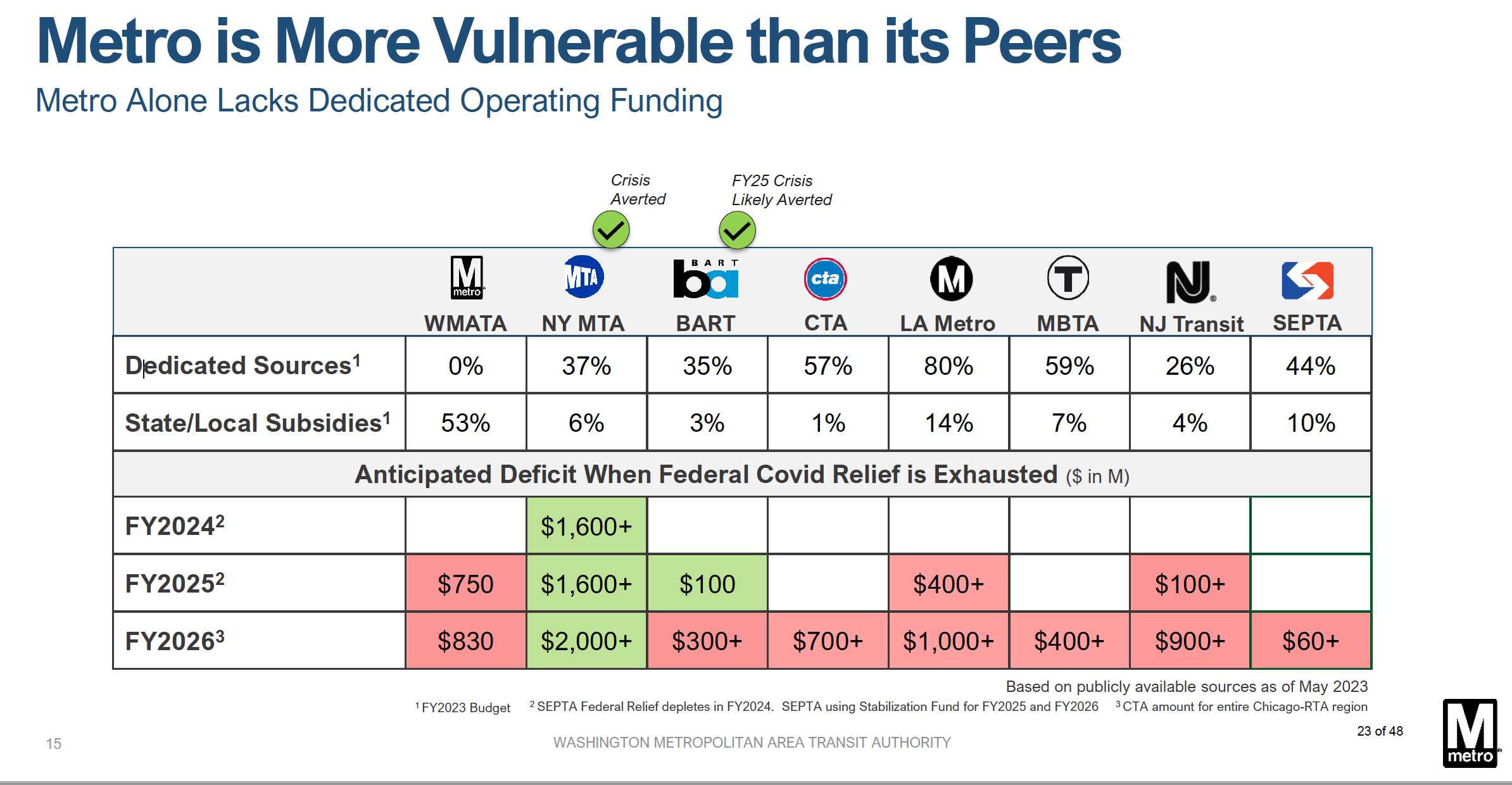

As mentioned earlier, much of this outlook is shared, to some degree, by most of the other major transit providers in the U.S. Interestingly, the WMATA presentation also estimates how badly some other major providers have it. One slide in the deck shows WMATA’s numbers next to the New York City MTA, San Francisco BART, Chicago CTA, L.A. Metro, Boston MBTA, New Jersey Transit, and Philadelphia SEPTA, for comparison.

The MTA was facing a fiscal cliff that dwarfed everyone else’s. CTA, L.A. Metro, and Jersey Transit are in about the same boat as WMATA, with BART and MBTA doing a little bit better and SEPTA doing better still.

The presentation notes that the New York political system has taken steps to avert MTA’s fiscal cliff permanently, and San Francisco and state leaders have at least kicked the can down the road by one year.

In New York, the deal to avert the cliff included a $1.1 billion per year payroll tax increase on employers in the five boroughs, a one-time $300 million appropriation from the state, a $165 million per year increase in NYC’s contribution for paratransit for two years, $500 million per year starting in 2026 from casino fees, and $400 million per year in operational savings.

In California, the new state budget allows transit agencies to convert their state capital funding to meet operational deficits, and also provides $1.1 billion over three years out of the cap-and-trade auction proceeds for capital or operating. This appears to have pushed BART out of fiscal danger for at least one more year (it remains to be seen how this will work for L.A. Metro).

What both the New York and California solutions have in common is that neither of them got any new money from Uncle Sam to fix their transit problems.

Politically speaking, it is important that New York took responsibility and solved its own problem without federal involvement. The New York MTA is either primus inter pares or the 800-pound gorilla of U.S. transit providers (depending on who you ask). In 2019, the MTA (including Metro North, the LIRR, and the MTA bus system) hosted 64 percent of all U.S. mass transit trips (3.79 billion UPT out of 5.97 billion nationally). That’s more than Chicago CTA, L.A. Metro, Boston MBTA, WMATA, SEPTA, Jersey Transit, Atlanta MARTA, Denver RTD, San Fran BART and Muni, and Portland Tri-Met combined, and that still leaves the MTA 1 billion trips ahead.

As a result of that disparity, during COVID, it seemed as if the MTA was in charge of negotiating federal aid on behalf of the entire transit sector. The MTA would tell Majority Leader Schumer’s office how much money they needed, then someone at the MTA or in the Senate would decide what multiplier of the MTA’s number would be needed for the rest of the country, and that is the amount of COVID aid that was provided.

Now that the MTA has fixed its problems, they (presumably) won’t be asking for a bailout from Uncle Sam to avert their fiscal cliff. Politically speaking, this makes it much more difficult for the remainder of the transit sector to get special dispensation from Congress in the future.