April 11, 2019

With this week’s announcement that the Mass Transit Account of the Highway Trust Fund has failed its solvency test for fiscal year 2020 and, absent a change in law from Congress, will face automatic spending cuts of around 12 percent, one question might spring to mind: how can the Highway Account of the Trust Fund pass its solvency test so easily (with future revenues $148 billion) being twice the level of unfunded liabilities ($74 billion)), while the Mass Transit Account fails the same solvency test, with $26 billion in future revenues being topped by $27 billion in unfunded liabilities?

The answer is that Congress has chosen to let mass transit spending get significantly farther ahead of its dedicated revenue stream than highways has gotten ahead of its revenue stream, comparatively speaking.

From the outset, it must be made crystal clear that mass transit does not get 20 percent of HTF revenues. The December 1982 highway bill that created the Mass Transit Account gave the account 20 percent of the gasoline and diesel tax increase levied by that law, and the subsequent 1990 and 1993 gas and diesel tax increases also saw 20 percent of those increases dedicated to transit. But the entirety of the gasoline and diesel taxes as they existed prior to 1983 (4 cents per gallon), and the entirety of the other HTF excise taxes on the trucking industry, are entirely devoted to the Highway Account.

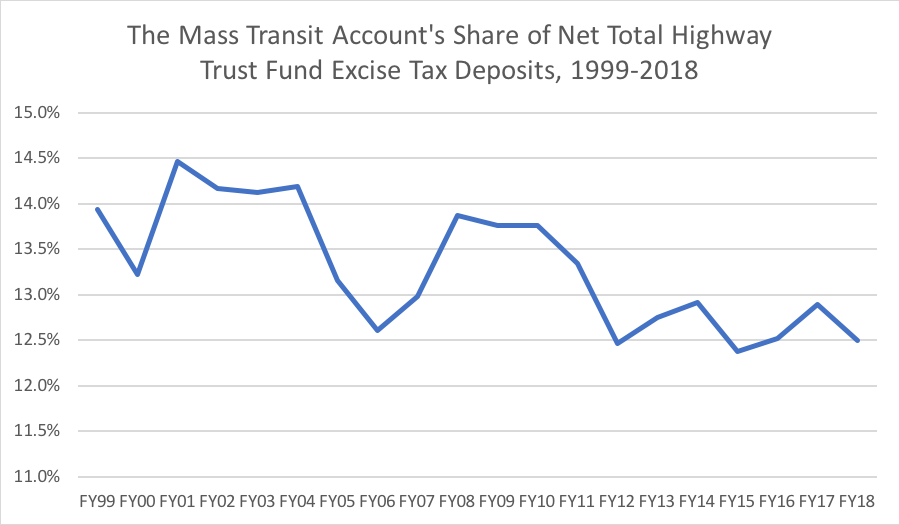

Since the creation of the Mass Transit Account in fiscal year 1983 through the end of FY 2018, it has received $127.5 billion in net excise tax revenue. This was 12.5 percent of the net total excise tax deposits in the Trust Fund over that period. Transit gets one-eighth, not one-fifth, of total HTF tax revenue. (This has varied a bit over time, since the trucking taxes are volatile, particularly the excise tax on new truck and trailer sales, which vary a lot with the business cycle.) Since the last gas tax was fully deposited in the Trust Fund (FY 1999), the Transit Account’s share of total tax revenues has varied from a high of 14.5 percent (FY 2001) to a low of 12.5 percent (FY 2012).

You would think that, in a system where a fund is broken up between two accounts, that new spending authority provided from each account would more or less track the ratio in which the tax deposits are divided between the accounts. You would be wrong.

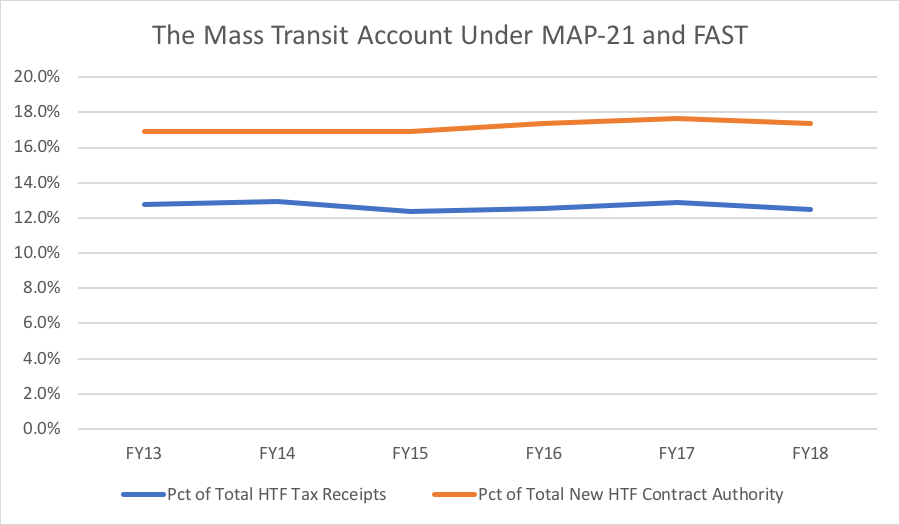

Under the SAFETEA-LU law, Congress began systematically giving mass transit spending a greater percentage of total Trust Fund spending authority than the Transit Account’s share of anticipated tax revenue. This trend has accelerated under the MAP-21 and FAST reauthorization laws. Over the last six years (2013-2018), the Mass Transit Account has averaged 12.7 percent of total Trust Fund tax collections – but Congress has provided that 17.2 percent of total Trust Fund contract authority be drawn on the Mass Transit Account.

Put another way, transit’s share of new spending is one-third greater than its share of the dedicated tax revenue, which is not sustainable (and would not be sustainable even if, overall, Trust Fund tax receipts matched new spending perfectly).

See this January 2019 ETW article for updated estimates of how much gasoline and diesel taxes would have to be increased to keep them both solvent. Bottom line: if you maintain the 80-20 highway-transit split of additional revenues, keeping the Highway Account solvent at baseline spending levels would require 80 percent of an immediate 8.5 cent per gallon tax increase, but keeping the Mass Transit Account solvent would require 20 percent of an immediate 13.5 cent per gallon increase.

In other words, the 80-20 split of new revenues may not work this time…