May 10, 2018

An unusually strong alignment of interests supporting fundamental restructuring of the nation’s air traffic control (ATC) system in the last few years gave many of us optimism that these important reforms would make it through Congress. But now that a Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) reauthorization bill has passed through the House without any moves in that direction, we can officially pronounce the patient dead. At least for now.

If the House and Senate can reconcile their reauthorization bills into law this year, the issue of fundamental ATC reform is probably off the table until a new FAA reauthorization bill is needed (the Senate bill runs through 2021 and the House bill through 2023).

But now that ATC reform efforts have been defeated for the time being, it’s worth taking a deeper look at why they failed. Of course, the Madisonian checks-and-balances system enshrined in our Constitution makes it much more difficult to pass a new law changing any existing system than to simply fight for the status quo. Fundamental reform of any existing government agency or program is always difficult.

And it certainly didn’t help that, of the major aviation stakeholders, the airlines were the most enthusiastic supporters of ATC reform – but the second-biggest carrier, Delta, wound up opposing the proposal, providing a divided front.

But in addition, ATC reform efforts pursued multiple policy goals, and each policy goal brought a different set of political opponents to the legislation. The combined opposition was just too great to be overcome.

The Eno Center for Transportation’s Aviation Working Group of stakeholders for several years examined the best ways to implement NextGen ATC technology. The Working Group concluded that only fundamental governance and funding reform of the existing federal structures could accelerate the implementation timeline.

Their final report on the subject proposes reforms that can be summed up in four alliterative policy goals, each of which is worth pursuing, alone or in combination with the other goals:

- Separate the ATC service provider from the aviation safety regulator, as most other developed nations have done.

- Insulate the ATC system from existing federal budget pressures (sequestration, spending caps, government shutdowns).

- Liberate the ATC service provider from cumbersome federal personnel and procurement rules.

- Allocate the costs of air traffic control services fairly to users through a system of bona fide user fees instead of the existing excise tax structure.

The final Eno report recommended that those four goals be achieved by taking ATC out of the FAA and turning it over to either of the following: a government-owned corporation (like Germany and Australia), or a non-profit private corporation (like Canada). Chairman Shuster’s legislation, which could never quite get enough votes to be brought up in the House, pursued most of these goals through the non-profit private corporation model.

(Me personally, I always thought the government-owned corporation model was a more practical way to go, simply because it would make the effort harder to demonize as “privatization” and would avoid most of the constitutional questions raised by Rep. DeFazio (D-OR) and others. But there has been a government-wide trend in recent decades away from creating new off-balance-sheet government entities, and political leaders of both parties in the House opposed the concept of a government corporation in private discussions. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are why we can’t have nice things.)

Each of those four policy goals – separating ATC from the government safety regulator, insulating ATC from the government budget, liberating ATC from government personnel and procurement rules, and allocating ATC costs fairly to users – brings a different set of opponents to the table. Let’s look at these in reverse order.

Allocating ATC costs fairly to system users. General aviation (all non-military aviation except transport for hire) interests have always felt that honest cost allocation of ATC services poses an existential threat to their way of life. This goes back decades.

The current system of funding the FAA through aviation excise taxes on aviation users deposited in the Airport and Airway Trust Fund began in 1970. At the House Ways and Means Committee’s 1969 hearings on the user tax proposal, the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) submitted a remarkable document for the hearing record. Called “User Charges: Panacea or Pitfall?”, the document didn’t just argue that general aviation should be exempt from user charges – it questioned the validity of the entire concept of user charges funding government services, going back to the Truman Administration.

But where aviation in particular was concerned, the AOPA report concluded:

It is AOPA’s view that improvement of air commerce is in the total public interest. As such, the public interest requirements for air commerce facilities have been and should be provided from general revenue funds. All of the direct users contribute through their general taxes.

This is consistent with other programs financed by Government. AOPA agrees with this policy. AOPA is, however, opposed to selective taxation to place the full burden of Government programs to improve air commerce on those who are direct users.

Why are GA interests so opposed to ATC cost allocation? Let’s look at a typical example. The best GA to non-GA comparisons are for the bigger private or corporate jets that use controlled airspace. To an air traffic controller, all blips moving at 40,000 feet in the same corridor are treated equally and use the same ATC resources, whether they are a fully loaded commercial airliner or a private jet with two or three passengers.

Why are GA interests so opposed to ATC cost allocation? Let’s look at a typical example. The best GA to non-GA comparisons are for the bigger private or corporate jets that use controlled airspace. To an air traffic controller, all blips moving at 40,000 feet in the same corridor are treated equally and use the same ATC resources, whether they are a fully loaded commercial airliner or a private jet with two or three passengers.

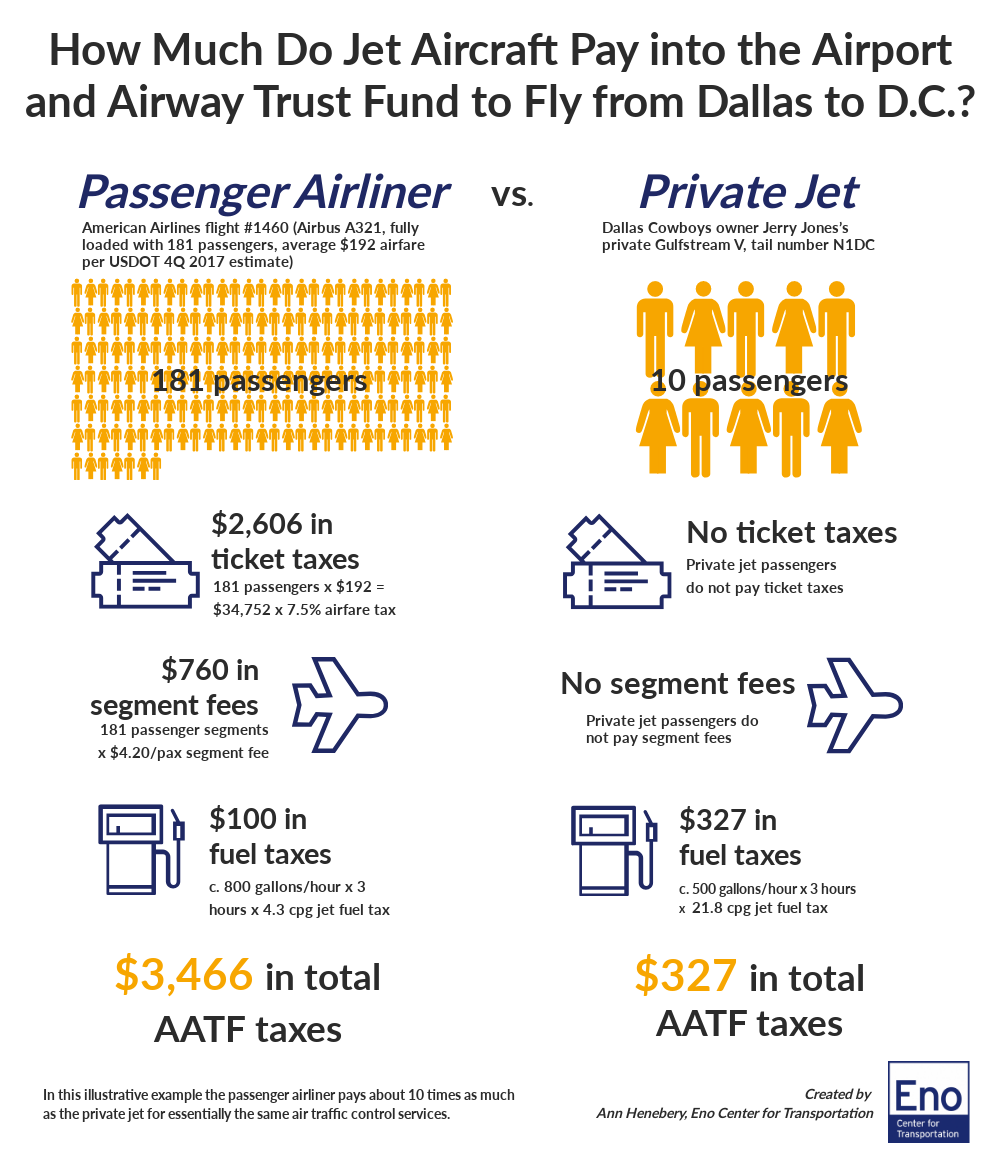

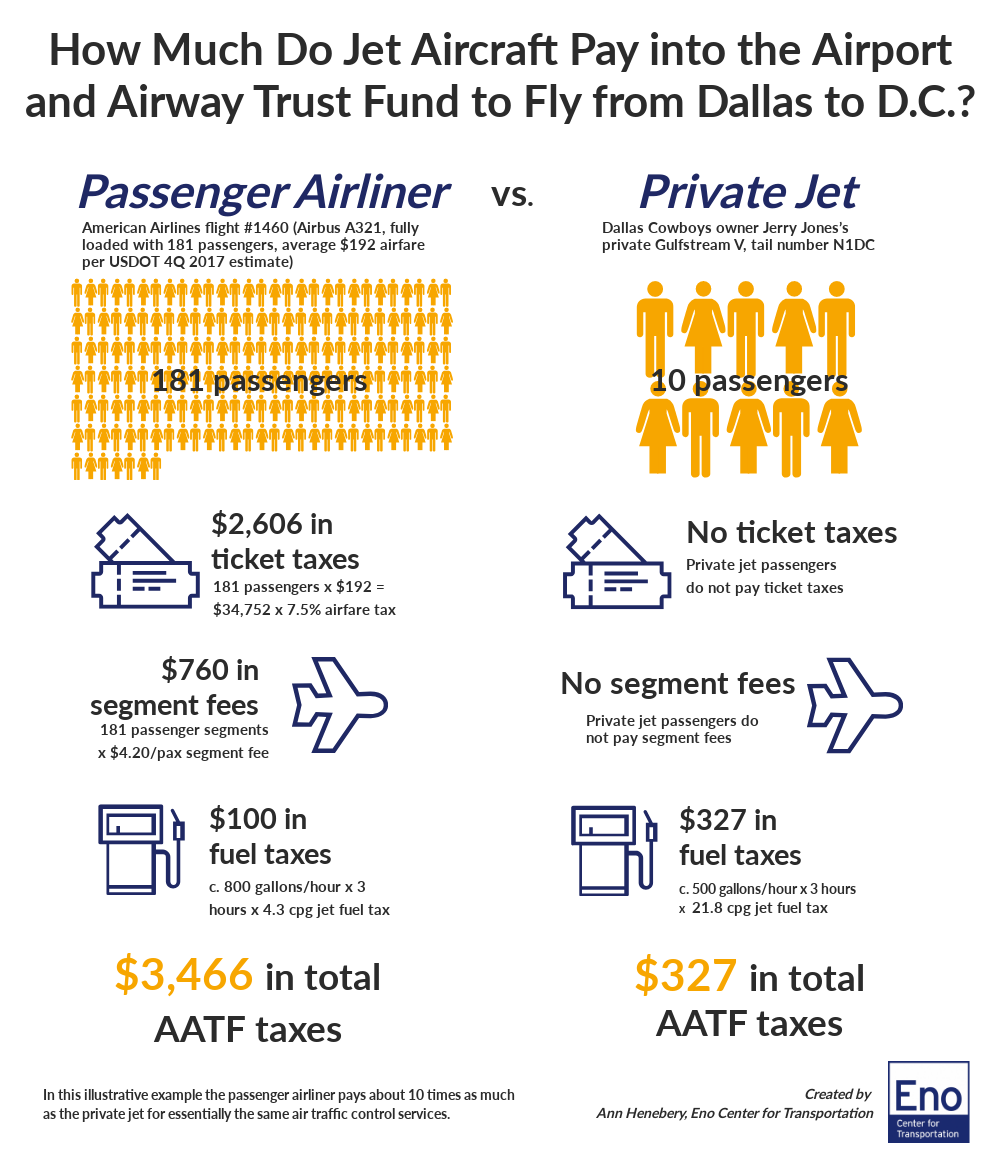

The multiple by which an airliner overpays for ATC compared to a private jet depends primarily on the number of passengers on the airliner, since airlines pay 7.5 percent of airfares and $4.20 per passenger per flight. We ran one illustrative example (Dallas to Washington DC) that showed conclusively that the airliner pays about ten times as much into the Airport and Airway Trust Fund as does the private jet. The multiple can be higher or lower depending on route distance and passenger load, but it’s almost impossible to run the numbers without the passenger airliner paying, at minimum, two to three times as much into the AATF as does an airliner for a flight between the same cities.

So it’s easy to see why the owners and operators of private jets see cost allocation as an existential threat that would cost them hundreds or thousands of dollars extra per flight.

The bulk of GA (your typical piston-engine, propeller-driven planes) uses a different set of ATC resources – they don’t always fly in controlled airspace, but they still use local radar and tower services, navigational beacons, and flight service stations. A 2007 cost allocation study from the FAA resulted in a Bush Administration proposal to increase the aviation gasoline excise tax from 19.3 cents per gallon to 70.0 cents per gallon in order to fairly allocate the FAA’s costs to the piston-engine segment of GA.

The general aviation lobby may be fairly small in numbers (AOPA has about 400,000 members and the other GA associations far less than that), but they are an influential bunch. On the small end, anyone who owns and flies their own Cessna probably has enough money and status to be plugged into the local political power structure in their community. On the large end, Corporate America relies on their aviation fleet for the business travel of their senior executives (the National Business Aviation Association is their trade group).

Having seen how GA successfully thwarted the 2007 proposal to allocate FAA costs via user fees and increased fuel taxes, Shuster’s bill tried to preempt the opposition, first by exempting all piston-engine aircraft from any user fees in the original version of his bill, and then later modifying his bill to exempt all GA from the new fees.

But it wasn’t enough – the GA interests saw the handover of ATC to a stakeholder-governed, cost-allocation-minded entity as making it more likely that Congress would then someday amend the law and allocate GA’s ATC costs to them. NBAA actively opposed the Shuster bill throughout, and the larger AOPA sided with them on the user fee issue on slippery-slope grounds.

(Also, the GA manufacturing industry is centered to a baffling extent in Kansas, so in the quest to get to 60 votes in the Senate, any fair cost allocation effort would start off lacking the two Senators in the reliably-red Jayhawk State.)

Liberating the ATC provider from government procurement and personnel rules. It is widely acknowledged that federal procurement rules make it difficult for agencies to carry out large high-tech procurement. And the USDOT Inspector General reported in 2016 that “FAA’s disappointing reform outcomes are largely the result of the Agency’s failure to take full advantage of its authorities when implementing new personnel systems, and not using business-like practices to improve its operational efficiency and cost effectiveness.”

Who could possibly be afraid of making air traffic control more efficient by making procurement easier and by allowing managers greater flexibility in personnel decisions?

For starters, one person’s “cumbersome personnel rules” are another person’s “hard-won labor protections.” Federal employee unions have spent decades of labor negotiations and Congressional lobbying putting those personnel rules in place.

While the air traffic controllers’ union (NATCA) supported ATC reform efforts this time around, the rest of the FAA’s unions did not. This in turn led the various alphabet soup organizations of federal employee unions to oppose the legislation – and since public employee unions are a key constituency of the Democratic Party, strong opposition from public employee unions usually leads to near-unified Democratic opposition.

Insulate the ATC provider from government budget pressures. Recent government shutdowns had a disastrous, multi-year effect on the training of future air traffic controllers. The 2013 federal budget sequestration had similarly broad negative effects on ATC. And the annual nature of the discretionary budget process makes it more difficult to do big NextGen procurements.

But protecting ATC from these pressures invariably means taking it out of the discretionary budget, which means taking ATC out of the reach of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. (This is true whether you make ATC a government-owned corporation or a private corporation.) Naturally, this is strongly resisted by the members of those same Appropriations Committees.

The bipartisan leaders of the House Appropriations Committee stated in a 2016 letter that “The annual oversight and funding role of Congress is critical to providing individual citizens and communities a voice, through their elected representatives, in the operation of our nation’s air traffic control system.”

And their Senate counterparts said in a separate letter that “The annual appropriations process provides the oversight of agency resources that is necessary to ensure accountability for program performance and a sustained focus on aviation safety. Congressional oversight also ensures that the FAA maintains a system that works across the aviation industry, including general aviation and small and rural communities as well as commercial airlines and large metropolitan cities.”

(Of course, if ATC is removed from the appropriators’ purview, that also means that rank-and-file members of Congress will no longer ask their appropriator colleagues for ATC-related legislative favors, and that the ATC entity will no longer have to jump through hoops every time the appropriators call, and that aviation interests will no longer have nearly as many reasons to make regular campaign contributions to appropriators.)

The Appropriations Committees are one of the last bastions of real bipartisanship in Congress. The annual appropriations bills are developed on a more-or-less bipartisan basis in committee, a cooperative process that has also carried through to appropriators of both parties supporting bipartisan omnibus appropriations legislation on the floor in recent years.

They are also bipartisan in responding to threats to their turf. Having most Republican appropriators as likely “no” votes on ATC reform, combined with the near-lockstep Democratic opposition because of the labor union issues, made getting to 218 “yes” votes in the House and 60 votes in the Senate even more difficult.

Separate the ATC provider from the government safety regulator. If the FAA were to have ATC taken away from it, it would lose about three-fourths of its employees and its annual budget. From the perspective of organizational self-interest, this is a losing proposition for the FAA, and many senior and mid-level FAA officials were resistant to ATC reform proposals.

This is not to say that FAA senior management was actively opposing ATC reform. But, under Obama Administration holdover Administrator Mike Huerta (who was serving a fixed five-year term that did not expire until January 2018), the FAA wasn’t really supportive, either. This contrasts with former FAA Administrator David Hinson, who was on board with the Clinton Administration’s 1993 ATC reform proposal, and former Administrator Marion Blakey, who was the leading force behind the Bush Administration’s 2007 ATC cost allocation via user fees proposal.

Many of the arguments for ATC reform revolve around longstanding complaints about how inefficient the FAA has been over the years on the transition to NextGen ATC. The FAA inherently starts from a position of self-defensiveness, denying that the NextGen problems identified by GAO, the Inspector General, and Congress are really that bad. (The natural response of any bureaucracy to external criticism is to stand fast and, like Kevin Bacon at the end of Animal House, shout “Remain calm! All is well!”) And this bleeds over into the general problems that come from trying to force massive and fundamental change on any entrenched bureaucracy.

It is also difficult for Congress to force restructuring and reform on the executive branch. Chairman Shuster started his efforts back in 2015, when Barack Obama was President and Anthony Foxx was Secretary of Transportation, and neither were supportive, for the reasons listed above.

The Trump Administration endorsed ATC reform efforts, in principle, early on, with a White House roundtable in February 2017, inclusion of the proposal in the first budget outline in March 2017, full-on endorsement in the full budget in May 2017, and a high-profile signing of an outline of its own proposal in June 2017.

But there was no follow-through. The White House never really weighed in behind the scenes with wavering Republicans in the House who had their doubts about the proposal. And even though Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao was also vocally supportive of the proposal, in this Administration in particular, departments and agencies are fearful of doing their own arm-twisting on Capitol Hill in support of their legislative proposals, since you never quite know when the White House’s position will change.

And the fact that chairman Shuster chose the private, non-profit corporation model instead of the government-owned corporation model for separating ATC from safety allowed opponents to define the debate as being about “privatization” instead of being about separating, insulating, liberating and allocating.

(The prospect of “privatization” also made the public employee unions double down on their opposition to reform (they were inclined to oppose it anyway because they don’t want existing personnel rules weakened). A private corporation obviously won’t have its employees counted as public employees, further weakening the unions which, as mentioned above, are integral parts of the Democratic Party coalition.)

It is a fascinating “what if” to wonder how the debate from 2016-2018 would have played out if chairman Shuster had taken the government-owned corporation route (or even if his original 2016 proposal hadn’t given quite so many seats on the ATC corporation board of directors to the big airlines). The “privatization” debate might have been avoided (but then again, it might have been replaced with a debate on the merits of creating a “Post Office in the sky”).

What next? At the end of the day, separating the ATC provider from the government safety regulator to avoid conflicts of interest is still an official recommendation of the United Nations aviation body, ICAO. Remaining part of the discretionary budget means that FAA operations and procurement are going to be squeezed once again when the Budget Control Act spending caps snap back to lower levels in fiscal 2020. Reports from watchdog agencies on the inefficiency of FAA procurement and personnel rules continue to pile up. And the costs of providing ATC services are still not fairly allocated to system users (in the case of private jets, grossly so).

Just because Congress has decided not to address these problems in any kind of fundamental way in 2018 does not mean that the problems are going away anytime soon.

The views expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Eno Center or of its Aviation Working Group.

For a complete (and I do mean complete) history of current and previous iterations of ATC reform, go to enotrans.org/faareform

Why are GA interests so opposed to ATC cost allocation? Let’s look at a

Why are GA interests so opposed to ATC cost allocation? Let’s look at a