Four months after creating a White House Task Force on Supply Chain Disruptions, and six weeks after appointing former Deputy U.S. Transportation Secretary (and glutton for punishment) John Porcari to be the President’s Port Envoy, the White House last week began rolling out initiatives to address the supply chain disruptions and cargo container port backlogs that have become ever more visible.

On October 13, the White House announced that the Port of Los Angeles would move to 24/7 operation, joining the adjacent Port of Long Beach, which went to 24/7 operation last month. The White House also announced that the West Coast longshore union (ILWU) had agreed to get its members to work those overnight shifts. Other retailers and shipping companies also committed to moving more cargo out of the ports at night.

To celebrate that announcement, the White House assembled a large group of principals from all points in the supply chain for a roundtable at the White House to address the backlog. Attendees were:

- Vice President Kamala Harris

- Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg

- National Economic Council Director Brian Deese

- Port Envoy John Porcari

- Gene Seroka, Executive Director, Port of Los Angeles

- Mario Cordero, Executive Director, Port of Long Beach

- Willie Adams, International President, ILWU

- James P. Hoffa, General President, Teamsters

- Greg Regan, President, Transportation Trades Department, AFL-CIO

- John Furner, President & CEO, Walmart U.S.

- Dr. Udo Lange, President and CEO, FedEx Logistics

- Nando Cesarone, President, U.S. Operations, UPS

- Brian Cornell, Board Chairman and CEO, Target

- Ted Decker, President and COO, Home Depot

- KS Choi, President and CEO, Samsung Electronics North America

- Matt Shay, President & CEO, National Retail Federation

- Peter Friedmann, Executive Director, Agriculture Transportation Coalition

- Chris Spear, President and CEO, American Trucking Associations

- Ian Jefferies, President and CEO, Association of American Railroads

- Suzanne Clark, President and CEO, U.S. Chamber of Commerce

- Geoff Freeman, President and CEO, Consumer Brands Association

- Jim McKenna, President and CEO, Pacific Maritime Association

According to the readout of the meeting, “Participants agreed to continue to work together, with the support of Port Envoy Porcari, on 24/7 operations at the two ports and across the entire supply chain. They discussed additional solutions to alleviate congestion and improve efficiency. This included a temporary expansion of warehousing and rail service, improving data tools and data sharing at the ports, and increasing both recruitment of truck drivers while improving the quality of trucking jobs.”

After the roundtable, President Biden came in to make his own remarks emphasizing the L.A. 24.7 announcement. Biden said “Traditionally, our ports have only been open during the week — Monday through Friday — and they’re generally closed down at nights and on weekends. By staying open seven days a week, through the night and on the weekends, the Port of Los Angeles will open — over 60 extra hours a week it will be open. In total, that will almost double the number of hours that the port is open for business from earlier this year.”

However, the first week of 24/7 operations hasn’t brought that much of a respite, because in order for it to work, trucks have to be able to come into the port, put offloaded containers onto a wheeled chassis, and haul the container out of the port to some warehouse or intermodal facility. And that has been the problem.

The head of the American Trucking Associations (ATA) told CNN this week that the problem is a driver shortage – 80,000 new drivers needed, according to him, up from a shortage of 61,500 pre-COVID.

But don’t say that around the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association (OOIDA), which told Freightwaves two months ago that the big trucking companies represented by ATA “perpetuated the myth of a driver shortage to promote policies that maintain the cheapest labor supply possible. In reality, evidence from the federal government and industry analysis shows that driver turnover is the problem.”

Training new drivers, and paying them enough to stick with the job, is a long-term solution. But a more immediate answer may involve not the truck or the trucker, but the trailer.

Here’s the kind of thing that (almost) redeems Twitter: the CEO of Flexport, Ryan Petersen, chartered a boat yesterday and did a three-hour tour of the LA/LB port complex, and summarized what he saw in a tweet thread today. He said that he cranes weren’t that busy unloading ships, because there was no more room on the ground for containers. And this, in turn, prevents the port complex from accepting any empty containers from inbound trucks.

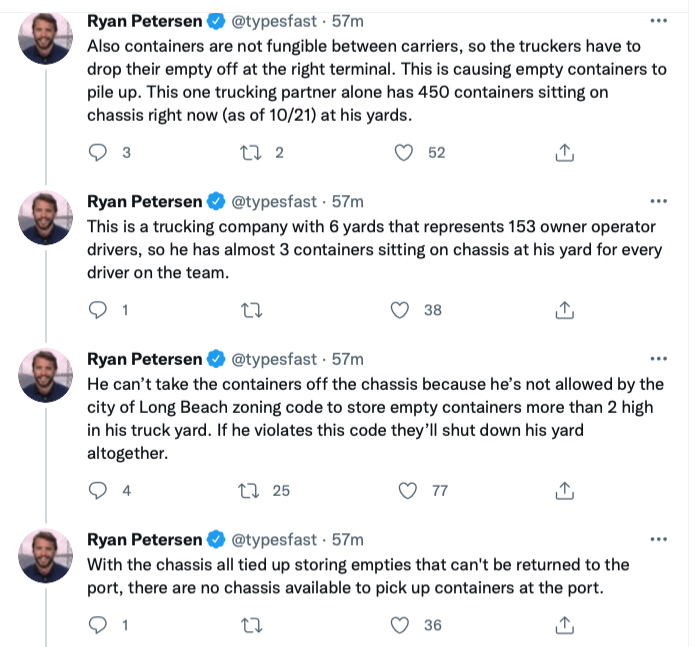

And this, Petersen says, is the cause of the less obvious part of the bottleneck: a shortage of wheeled chassis upon which to carry containers. If a trucking company can’t get the empty container off of the chassis, they can’t take that chassis to the port and pick up a new container. Here is how Peterson described the vicious circle:

Petersen ended his tweet thread with a list of suggestions, some more practical than others. The more practical involved Governor Newsom temporarily waiving local zoning codes to allow empty containers to be stacked five-high for a few months (you can hear the NIMBY complaints already) to free up chassis, and having the National Guard and military loan all their unused chassis to local ports for six months. (Some of this other solutions were less practical.)

But Petersen was probably correct when he said that “You should always choose the most capital intensive part of the line to be your bottleneck. In a port that’s the ship to shore cranes. The cranes should never be unable to run because they’re waiting for another part of the operation to catch up.”

In the long term, once the chassis shortage is sorted out and the container and ship backlog reduced, attention can turn to long-term problems, including the (possible) driver shortage and relative inefficiencies of U.S. container ports compared with foreign ports. And this is where we probably lose cooperation with the ILWU, because at major container ports in other countries (Rotterdam, Shanghai), efficiency has come through automation, and automation usually results in fewer secure, well-paid union jobs.

The House Appropriations Committee drafted its fiscal 2022 Transportation-HUD appropriations bill before the supply chain crisis really became acute. That bill would appropriate $300 million for grants to improve freight operations at U.S. seaports. However, the House bill contains a new restriction on that port grant money, presumably at the behest of the ILWU or its allies:

Provided further, That projects eligible for amounts made available under this heading may not include the purchase or installation of fully automated cargo handling equipment or terminal infrastructure that is designed for fully automated cargo handling equipment: Provided further, That for the purposes of the preceding proviso, ‘fully automated cargo handling equipment’ means cargo handling equipment that is remotely operated or remotely monitored and does not require the exercise of human intervention or control:

The Senate companion bill, released this week, contains no such provision. But the fact that the House included such a provision in a bill at all goes to show where the long-term fault line on increasing port efficiency will be.