February 15, 2018

President Trump submitted his long-awaited infrastructure initiative to Congress on Monday. In a formal message to Congress, Trump wrote:

For too long, lawmakers have invested in infrastructure inefficiently, ignored critical needs, and allowed it to deteriorate. As a result, the United States has fallen further and further behind other countries. It is time to give Americans the working, modern infrastructure they deserve.

To help build a better future for all Americans, I ask the Congress to act soon on an infrastructure bill that will: stimulate at least $1.5 trillion in new investment over the next 10 years, shorten the process for approving projects to 2 years or less, address unmet rural infrastructure needs, empower State and local authorities, and train the American workforce of the future.

ETW has summarized the proposal here and here.

Reaction to the plan on Capitol Hill was mixed. Some called it a ” thoughtful, detailed, and responsible blueprint” (Speaker Ryan) and “a a solid foundation for [Congress] to begin its work on a broad, bipartisan bill” (Sen. Roy Blunt, R-MO). Others denounced it as “a puny infrastructure scam that fully fails to meet the need in America’s communities” (Minority Leader Pelosi) and “an attempt to sell our nation’s infrastructure and create windfall profit for Wall Street while rolling back environmental protections” (Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-OR).

More telling was the muted response from the legislators who are going to have to shepherd some kind of an infrastructure plan through Congress if it is indeed going to happen. Check out the statement of Chairman Bill Shuster (R-PA) who said “I welcome the release of his Administration’s principles today as Congress prepares to develop an infrastructure bill. There is widespread desire to work together on this effort. Passage of an infrastructure bill will require presidential leadership and bipartisan congressional cooperation.” Or the joint statement of Chairman John Thune (R-SD) and ranking member Bill Nelson (R-FL), where Thune said only that “President Trump has offered us direction” and where Nelson said he would work with Thune.

Criticism of the plan has focused on three areas: the lack of a “pay-for,” the reduction of other infrastructure programs in the FY19 budget at the same time, and the overall low federal cost share of the plan.

Gas tax. The initial round of criticism again asked, “how are we supposed to pay for this plan?” But that was on Monday. And under the Trump Administration, things can escalate quickly.

On Tuesday, Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao appeared at a White House news briefing to discuss the infrastructure plan. (She also accepted a personal check sent by President Trump for one-fourth of his annual salary ($400,000 a year before taxes), which he donated to the INFRA competitive grant program established by the FAST Act.)

During that briefing, the following exchange took place, during which Chao reiterated what has been the standard Administration line on the gas tax:

Q Thank you, Secretary Chao. As you know, the federal gas tax has remained at 18.4 cents per gallon since 1993. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has advocated an increase in the gas tax of 25 cents per gallon. The truckers — the American Trucking Associations recommended a 20-cent-per-gallon increase in the gas tax. What’s your view on this subject?

SECRETARY CHAO: Well, the President has not declared anything out of bounds, so everything is on the table.

The gas tax, like many of the other pay-fors that are being discussed, is not ideal. There are pros and cons. The gas tax has adverse impact, a very regressive impact, on the most vulnerable within our society; those who depend on jobs, who are hourly workers. So these are tough decisions, which is why, once again, we need to start the dialogue with the Congress, and so that we can address these issues on this very important point.

Then, on Wednesday, the President hosted several House and Senate committee chairmen and other senior committee members to discuss the infrastructure plan. Trump had some opening remarks, and then the reporters all left the room. What happened afterwards, according to several participants, was a remarkably free-wheeling and open discussion during which President Trump allegedly not only said that he would accept a gas tax increase to pay for the plan, but also that he could sell it to his base voters and their allies in Congress.

(Ed. Note: Signing a bill is the easy part. Getting the votes is the hard part.)

In particular, members present brought up the fact that the U.S. Chamber of Commerce is promoting a 25 cent per gallon motor fuels tax increase (5 cents per year for 5 years) plus indexation for inflation and for increased fuel efficiency. An ETW analysis found that that the proposal could gross north of $380 billion (the start date of the indexation and the indices you use give some leeway in estimates). The American Trucking Associations are promoting a 20 cent per gallon increase.

Trump reportedly had no problem with those numbers – but given how consistent his Administration’s line about “nothing is off the table” has been, this is not surprising. What is more surprising is that he apparently told the legislators present (according to second-hand accounts) that he would take the lead on getting the tax increase through and that he thought he could sell it to Congress and the electorate.

It will be even more surprising if President Trump can sell a gas tax increase to the legislators and voters to whom it needs to be sold – conservative Republicans in Congress and Trump voters in the country as a whole.

The problem with the gas tax as a pay-for is that, really, the first call on increased gas tax revenues is the Highway Trust Fund, which will default again in 2021 because Congress keeps increasing spending but has not increased the gas tax devoted to the Trust Fund since 1997. (The tax itself was last increased in 1993 but was for general fund deficit reduction only – the money was not transferred to the Highway Trust Fund until 1997.)

If you raised the gas tax immediately, you would need an increase of about 8.5 cents per gallon just to keep the Trust Fund from defaulting for the next 10 years at baseline spending levels.

Expanding the use of gas tax receipts to cover types of infrastructure beyond highways and transit would be even more politically problematic.

Offsetting budget cuts. Starting even before the budget and the infrastructure plan were released, Democrats were criticizing the plan because the cuts in other infrastructure programs in the FY19 budget would allegedly counteract most or all of the other infrastructure spending in the new proposal.

True or not true?

The Administration’s budget request does indeed propose reductions in some transportation infrastructure programs. The Administration proposes to end the Federal Transit Administration’s Capital Investment Grants program (new subways and light rail) once ongoing projects are paid off, and they also propose to kill the TIGER grant program administered by the Secretary of Transportation.

Assuming new starts would otherwise putter along at $2.2 billion per year (the recent average), if they kill the program after they pay off the $4.7 billion in remaining commitments to ongoing projects, that would cut the program by $17.3 billion over ten years. The TIGER program averages $500 million per year, so that is another $5.0 billion reduction. The Administration has been explicit that the programs in the new infrastructure plan are to replace new starts and TIGER. They also propose to kill several small new railroad grant programs that totaled about $0.1 billion last year, so call that another $1.0 billion saved.

The budget proposes cuts in the Army Corps of Engineers water resources program of about $1.4 billion below last year, so call that $14 billion over 10 years as well. A rural water infrastructure program at the Agriculture Department averaging about $0.5 billion per year would also go, so $5.0 billion there.

17.3 + 5.0 + 1.0 + 14.0 5.0 = $42.3 billion at least.

The Budget also proposes to cut Amtrak, but the cuts appear to be in operating subsidies, not capital (i.e. not in infrastructure). One should not conflate operating and capital costs, ever, but most especially in a debate on infrastructure. Operating costs are not infrastructure. (There’s a reason why it’s called the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, not the Transportation is Infrastructure Committee.)

The budget also cuts a bunch of HUD and other programs that are a kind of infrastructure but are not the kind of infrastructure that is covered by the President’s bill.

So it is true that somewhere in the ballpark of $42 billion, at least, should be deducted from the spending totals in the President’s plan because those are existing infrastructure programs that would be specifically replaced by programs in the President’s plan.

Rep. DeFazio was using a much larger figure, around $168 billion, because (a) he was using the Amtrak money in his calculation but more importantly (b) he was also counting the ten-year cost of Highway Trust Fund insolvency starting in 2021, which President Trump’s FY19 budget would not address, in his total. The budget estimates this at just over $122 billion from 2021 until the end of the 10-year budget window in 2028.

Elsewhere in this issue, we have a full analysis of the budget’s impact on the Highway Trust Fund, but suffice it to say that OMB has changed its budget presentation this year to show the slowdown in outlays from a Highway Trust Fund insolvency as costs built into the baseline and not a policy change. We believe this is a better way to present it than current law, and it’s not really fair to say that the Trust Fund bankruptcy is a Trump policy because the problem was baked into the cake the moment the FAST Act was signed into law in December 2015, almost a year before Donald Trump was elected President. (Trump gets no points for bravery by dodging the issue, but it is not a problem that the Trump Administration inherited.)

Using this analysis, it’s just as fair to say that the FAST Act, billed as a $300 billion bill by its sponsors, was really a $200 billion bill because at the time the CBO baseline showed that the spending levels in the bill would necessitate $100 billion in future bailouts of the Trust Fund. Fair is fair.

It is better to say that the real cost of Trump’s infrastructure plan is whatever his net total is ($200 billion? $158 billion? Whatever.) PLUS the $122 billon in Trust Fund solvency costs. Because stakeholder groups and states are adamant that fixing the hole in the Trust Fund is more important than creating any new programs.

Federal share. The President’s plan has taken criticism for the fact that the $100 billion in “incentive” grants apparently only have a maximum federal matching share of 20 percent and are designed to incentivize state and local governments to raise non-federal revenue to fund the rest of the infrastructure matched by those grants. Critics point out that the existing federal match for non-Interstate highways is 80 percent and is 90 percent for Interstates and that the match for transit formula capital grants is 80 percent and for new subways and light rail is 50 percent.

The White House responds that the existing programs are only for a subset of all infrastructure (roads on the federal-aid system and only certain transit costs) and that when you look at all infrastructure, the federal cost share is close to 20 percent, so additional incentive grants at 20 percent aren’t aren’t a real deviation from the norm.

Who’s correct?

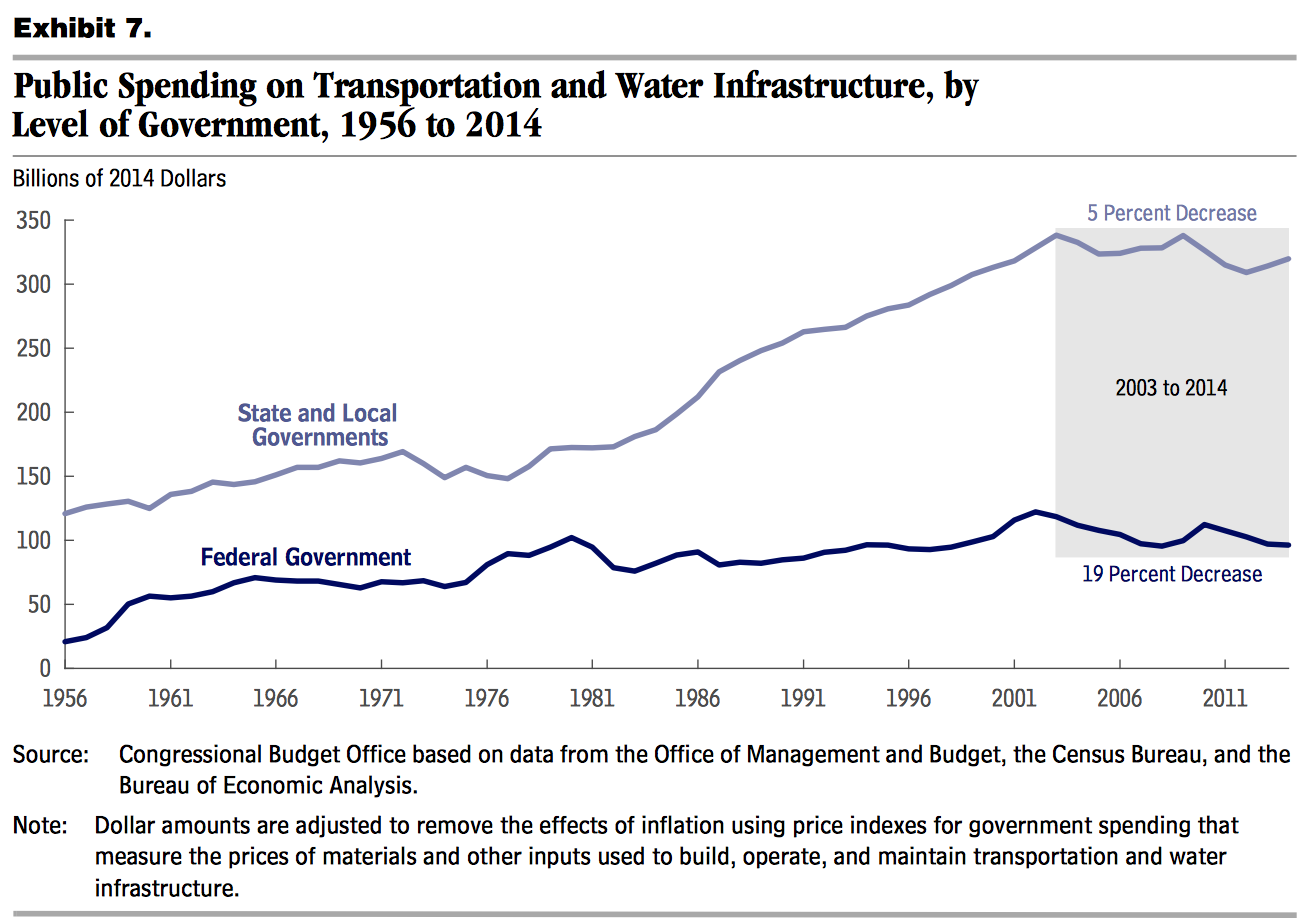

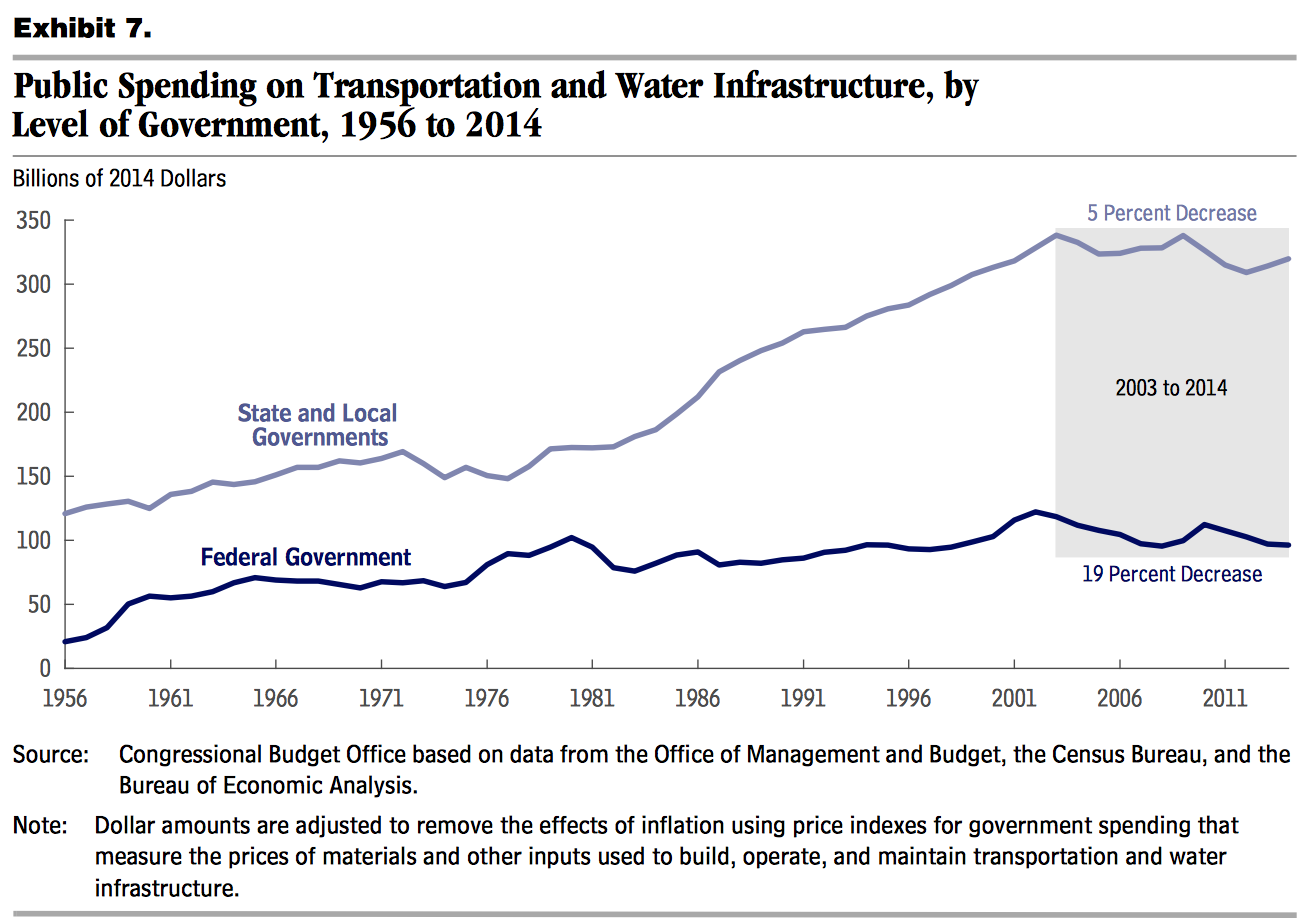

In March 2015, the Congressional Budget Office produced an invaluable report entitled Public Spending on Transportation and Water Infrastructure, 1956 to 2014. (Everyone should read it and bookmark it.) In terms of constant 2014 dollars, here is how the money spent by the federal government over those years compares to the amount of money spent by state and local governments combined:

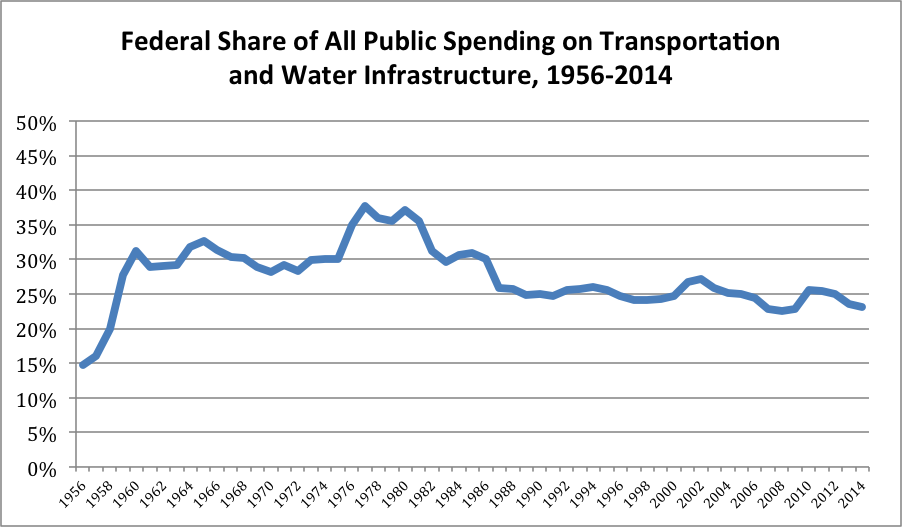

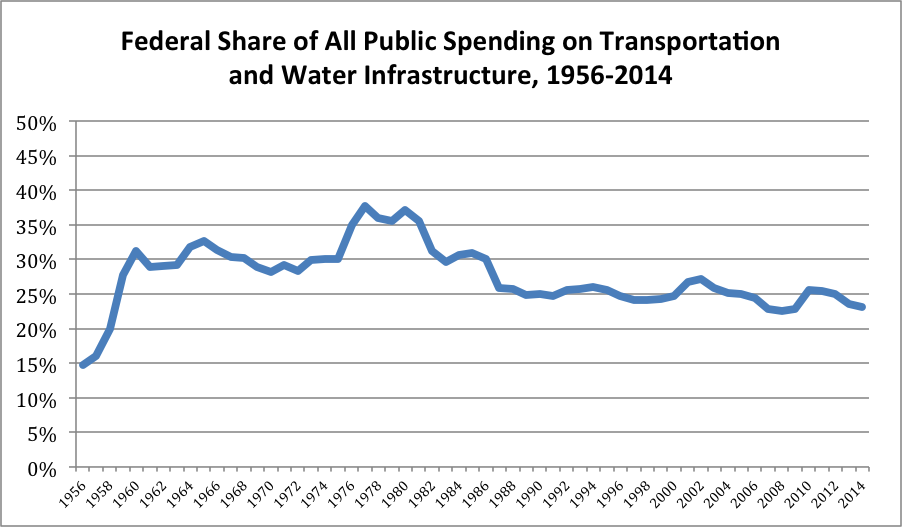

The CBO website also has links to spreadsheets containing the background data of the report. Using those, we were quickly able to take the raw data that CBO used in the above chart and generate our own chart showing the total federal share of all public spending on transportation and water infrastructure during this time.

The data show that the big change was construction of the Interstate Highway System. Pre-Interstate, the federal share was around 15 percent. The Interstate program, at a 90-10 federal-state split, boosted the overall federal share to the 30-35 percent range. But once the Interstate was largely built out by the mid-1980s, federal funding dropped to a “new normal” of around 25 percent, since new federal funding programs for mass transit, railroads, and drinking water and wastewater had been created in the meantime.

So the White House is generally correct to say that, on the whole, the federal share of all transportation and water infrastructure is only 23 percent. However, critics of the plan are also correct to say that certain individual programs that would be eliminated by the President’s budget pay a higher share – the mass transit new starts program currently pays up to 50 percent of a new subway or light rail system (and can be combined with other federal funds), and the TIGER program pays a federal share of up to 80 percent of the costs of major projects (higher for projects in rural areas). Any states or localities who were counting on a 50 to 80 percent federal match for a project under existing programs and then got that project shunted into a program that only matches 20 percent would be understandably unhappy.

It’s other, non-transportation grants to state and local governments in the budget that should have people concerned. In terms of overall federal grants to state and local governments, according to Table 14-1 in the Analytical Perspectives volume of the budget, the federal government would outlay $42.4 billion from the Infrastructure Initiative in 2019 if the plan were enacted immediately, almost all of it from the rural formula block grant program. Total USDOT outlays for grants would drop slightly, due to the expiration of some old stimulus and other emergency funds provided years ago. Autopilot-driven Medicaid grants would jump from $400.4 billion to $412.0 billion. And all other federal grants to state and local governments would drop by 11 percent, from $263.4 billion to $340.7 billion.

|

FY 2017 |

FY 2018 |

FY 2019 |

| USDOT |

$64,639 |

$64,203 |

$63,872 |

| Infra. Plan |

$0 |

$0 |

$42,365 |

| Medicaid |

$374,682 |

$400,388 |

$412,033 |

| All Other |

$235,379 |

$263,395 |

$230,724 |

| TOTAL |

$674,700 |

$727,986 |

$748,994 |