March 2, 2018

While much of the conversation around self-driving technology has revolved around the potential safety benefits, the White House and politicians are now pointing to yet another silver lining: economic development.

With the AV industry estimated to become a $7 trillion market by 2050, political leaders have seized on the opportunity to attract jobs and investments to their constituencies.

The United States is currently seen as the global leader on this emerging technology, thanks to the scores of tech firms and automakers researching and developing automated vehicles (AVs) in Silicon Valley and Michigan. But as countries like China, Japan, and the U.K. invest incredible sums of money in AV technology and craft the policies to support it, Congress and the Trump Administration have began to identify AVs as a critical part of American economic competitiveness.

Last month, the White House released the Economic Report of the President, which outlines President Trump’s “pro-growth agenda” for the nation in 2018. The agenda rests on three main pillars: tax cuts, tax reform, and smart deregulation.

The report examines the vital role of transportation and infrastructure in driving economic growth, and the current challenges faced by the transportation industry, noting that:

“Although the Nation’s transportation network, water facilities, communications sector, and energy infrastructure are the envy of many, studies and media reports increasingly point to problems with congestion, service quality degradation, insufficient funding, fairness and affordability, and the lack of coordinated, forward-looking infrastructure management in the public sector.”

The White House cites numerous studies to support this point, including the American Society of Civil Engineers’ (ASCE) most recent infrastructure report card, which gave the U.S. a D+ grade. ASCE estimated it would take a whopping $4.6 trillion to repair the nation’s transportation, water, communications, and energy infrastructure – which is at least three times as much money as the president’s infrastructure proposal would theoretically generate. (See ETW editor Jeff Davis’ op-ed in The Hill this week for an analysis of how Trump’s infrastructure plan hopes to leverage $200 billion to create $1.0-1.5 trillion in funding)

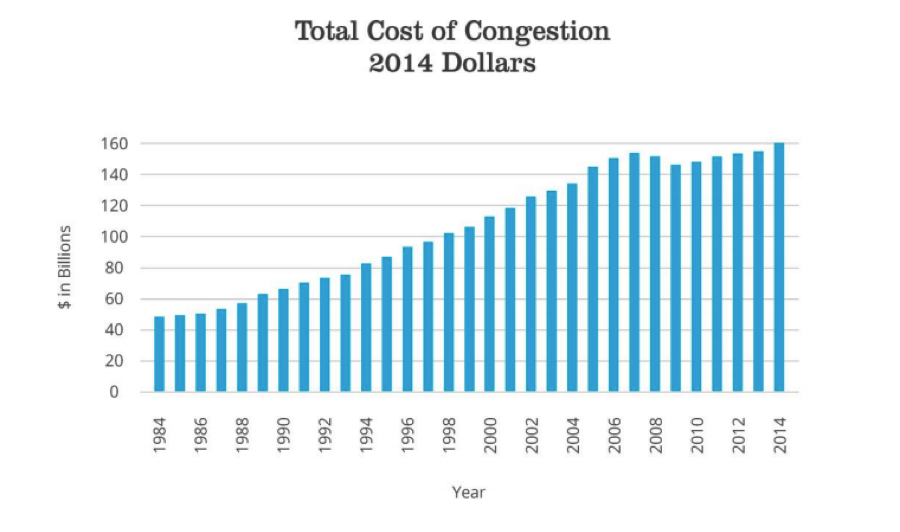

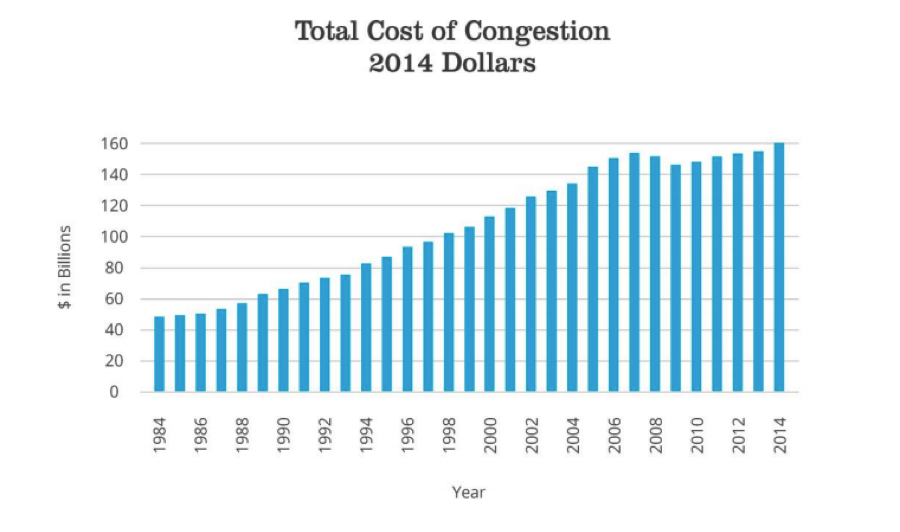

Roads had it especially bad in the ASCE report, garnering a meager D grade. The condition of the nation’s roadways was also found to cost Americans $160 billion in wasted fuel and lost time due to congestion, plus $120.5 billion in extra vehicle repairs and operating costs from driving on poorly maintained roads.

(Source: 2017 Infrastructure Report Card – Roads, ASCE)

The White House’s economic report acknowledged these challenges before briefly mentioning that AVs “will also affect the value of specific infrastructure investments” and “alter the future use of existing infrastructure, the organization of business activity, and even residential density and location patterns.”

To some extent, this is true.

As discussed in a recent ETW op-ed, AVs present an opportunity to rethink land use policies and encourage higher density development. But that’s the best-case scenario.

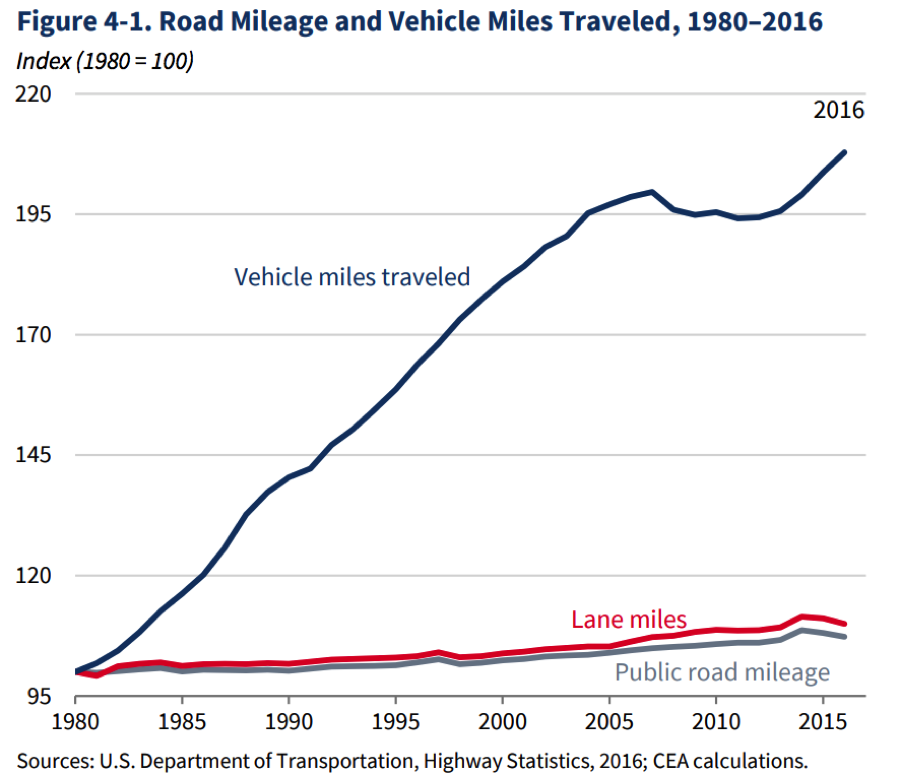

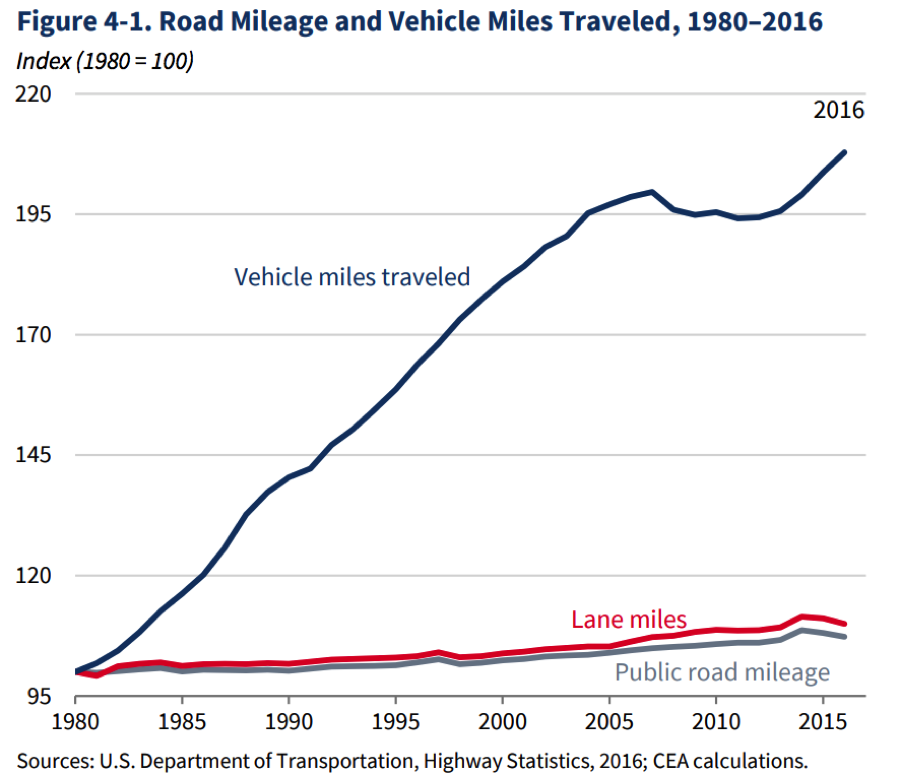

The convenience of commuting in fully autonomous vehicles could result in people choosing to live further away from their workplaces, increasing both sprawl and vehicle miles traveled (VMT). This would contribute to more wear-and-tear on roadways and, in turn, a need for greater infrastructure investment.

Effectively, AVs could do the exact opposite of altering the future use of existing infrastructure. But it is much too soon to change infrastructure investments or designs for AVs, as both the utopian and dystopian impacts of AVs are plausible. Moreover, the widespread commercial deployment of AVs remains five, if not ten or twenty, years away.

Since the economy has bounced back from the Great Recession, VMT has been creeping back up from year to year. Waiting for AVs to be a potential silver bullet, instead of making sufficient investments in infrastructure could be disastrous.

The report later dedicated most of a page (page 171, box 4-1) to exploring the source of the White House’s interest in AVs. It argued that AVs could reduce congestion because “driverless vehicles would be “able to drive much closer to other vehicles in a safe manner, and be able to accelerate and decelerate more quickly. And these vehicles would have the potential to prevent collisions and reduce regular and incident delays by creating a smoother traffic flow.”

The White House concluded its thoughts on AVs by assessing transportation technology through a historical lens:

“These potential sizable macroeconomic effects of advances in transportation technology are not surprising in light of the historical evidence on the positive benefits to the U.S. of improvements in mobility. Krugman (2009) elaborates on how railroads, by reducing transportation costs, facilitated large-scale production and radically transformed the U.S. economy into differentiated agriculture and manufacturing hubs. Similarly, given their potential to reduce congestion and increase safety, autonomous vehicles are an exciting area of ongoing scientific research.”

But – depending on one’s perspective – it was not all good news. The report argued that rapid technological change and disruptive transportation services (e.g., Uber, Lyft) present the “biggest risks and opportunities” facing the transit sector. The White House suggests that transit agencies, which are already experiencing decreasing ridership and budget pressures, could be threatened by the advent of AVs, transportation network companies like Uber and Lyft, and “smart” road and highway infrastructure. (While the term “smart” was not defined, it is probably safe to assume they were referring to connected infrastructure technology that would support vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure communications.)

However, a part of the Administration also appears to see automation as a potential benefit for transit agencies. In December, the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) launched its Strategic Transit Automation Research (STAR) initiative, which seeks to help transit agencies in adopting AVs by providing guidance, funding for pilot projects, and eventually revising regulations that would not be compatible with automated transit services.

The STAR Plan is but one piece of the Administration’s ongoing efforts to encourage the development of AVs. Under Secretary Elaine Chao, USDOT has enthusiastically embraced the potential benefits of AVs and worked on policies to encourage their continued development in the United States.

As ETW first reported, USDOT is currently working on the third iteration of its federal AV policy document, tentatively named Automated Vehicles 3.0. During her keynote at the department’s Automated Vehicle Summit on March 1, Secretary Chao closed with a summary of the Administration’s vision:

“…[C]reativity and innovation are part of the great genius of America – one of its hallmarks. We must nurture and preserve this legacy. Working together we can help usher in a new era of transportation innovation and safety, and ensure that our country remains a global leader in autonomous technology.”