July 18, 2018

Prompted by the 50th anniversary of the decision to move federal mass transit programs from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to the Department of Transportation, we have been examining the issue of whether or not mass transit was more about transportation or more about urban development and land use. Parts one, two and three of the series got through the move to DOT in summer 1968 and describes how transportation won the argument.

This part, which is happily coincident with today’s Senate hearing on President Trump’s proposed executive branch reorganization plan, explores how the Nixon Administration in 1971 did a complete conceptual about-face on the issue.

Nixon reverses course. On July 1, 1968, federal responsibility for mass transit was transferred from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, where it began, to the Department of Transportation.

Less than three years later, in March 1971, President Nixon proposed to take mass transit out of DOT and give it back to a beefed-up version of HUD as part of a sweeping plan for fundamental government reorganization.

Under President George Washington, the government divided executive branch leadership under five Cabinet officers – the Secretaries of State, War, and the Treasury, plus the Attorney General and the Postmaster General. A Department of the Navy was added in 1798. By 1971, those had been consolidated into four Departments that were descendants of those offices: State, Defense, Treasury and Justice. (The Post Office was in the process of being spun off into a private company.)

After the original pre-1800 flurry of activity, Congress didn’t start establishing new Cabinet-level Departments again until 1849 (Interior). It was followed by Agriculture (1889), Commerce and Labor (1903, with Labor being spun off into its own Department in 1913), Health, Education and Welfare (1953), Housing and Urban Development (1965) and Transportation (1966).

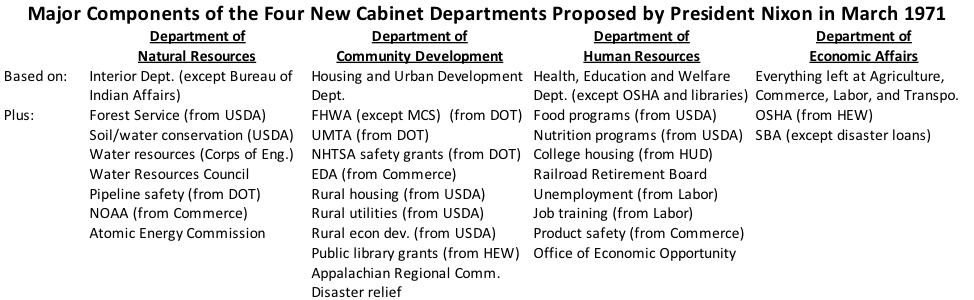

Nixon’s plan was to take the seven new non-defense Departments that had been created since 1800 and consolidate them into four. But instead of organizing them around what governmental function was being served by the various programs within a department, the Nixon approach was revolutionary – it was to move the programs around according to the ultimate governmental goals being served.

In his message to Congress on March 25, 1971 (House Document 92-75), Nixon wrote:

The problem is that as our society has become more complex, we often find ourselves using a variety of means to achieve a single set of goals. We are interested, for example, in economic development which requires new markets, more productive workers and better transportation systems. But which department do we go to for that? And what if we want to build a new city, with sufficient public facilities, adequate housing, and decent recreation areas – which department do we petition then?

We sometimes seem to have forgotten that government is not in business to deal with subjects on a chart but to achieve real objectives for real human beings. These objectives will never be fully achieved unless we change our old ways of thinking. It is not enough merely to reshuffle departments for the sake of reshuffling them. We must rebuild the executive branch according to a new understanding of how government can best be organized to perform effectively.

The key to that new understanding is the concept that the executive branch of the government should be organized around basic goals. Instead of grouping activities by narrow subjects or by limited constituencies, we should organize them around the great purposes of government in modern society. For only when a department is set up to achieve a given set of purposes, can we effectively hold that department accountable for achieving them. Only when the responsibility for realizing basic objectives is clearly focused in a specific governmental unit, can we reasonably hope that those objectives will be realized.

-Richard Nixon, Message to Congress, March 25, 1971

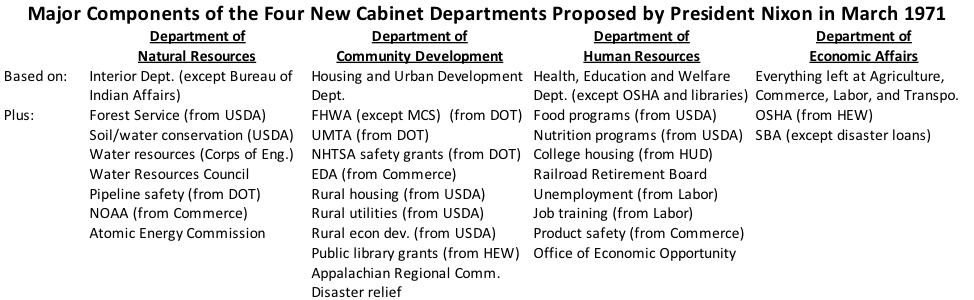

Nixon identified four overarching goals of government and proposed to rearrange the pieces of the seven post-1800 Cabinet Departments, as well as a few independent agencies, within those four goals.

- Goal #1 – “to conserve, manage and utilize our [natural] resources in a way that protect the quality of the environment and achieve a true harmony between man and nature” – Department of Natural Resources.

- Goal #2 – “to help build a wholesome and safe community for environment for every American” – Department of Community Development.

- Goal #3 – “to assist the development of individual potential and family well-being” – Department of Human Resources.

- Goal #4 – “to promote economic growth, foster economic justice, and encourage more efficient and more productive relationships among the various elements of our economy and between the United States economy and those of other nations” – Department of Economic Affairs.

Three of the proposed new Cabinet Departments – Natural Resources, Community Development, and Human Resources – would be built around one of the existing Departments each, (Interior, HUD, and HEW, respectively) which would lose few to none of their existing components. The Economic Affairs Department would take everything that was left.

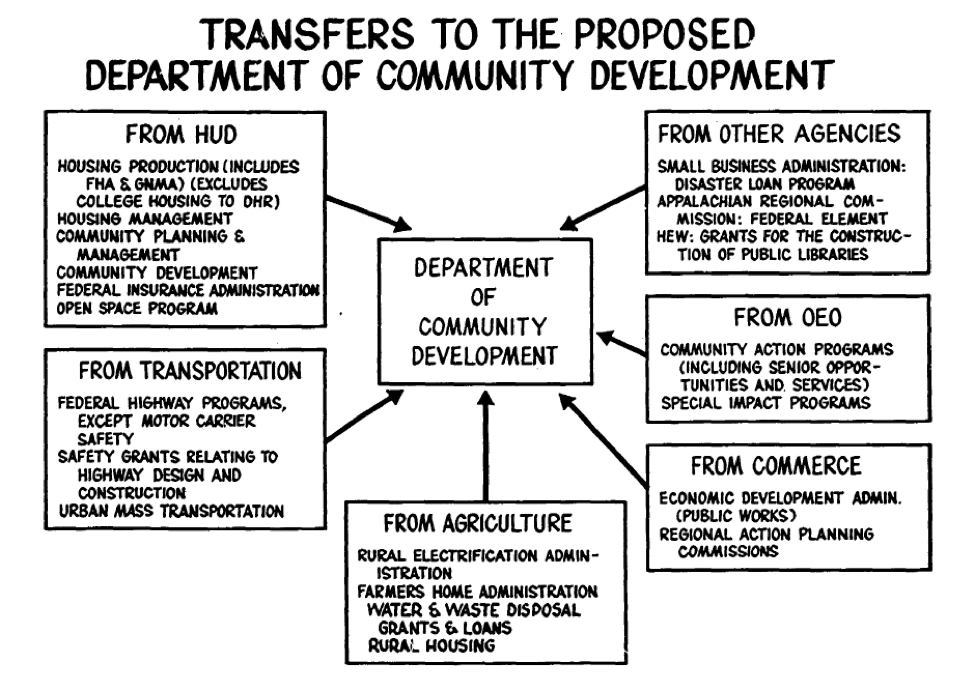

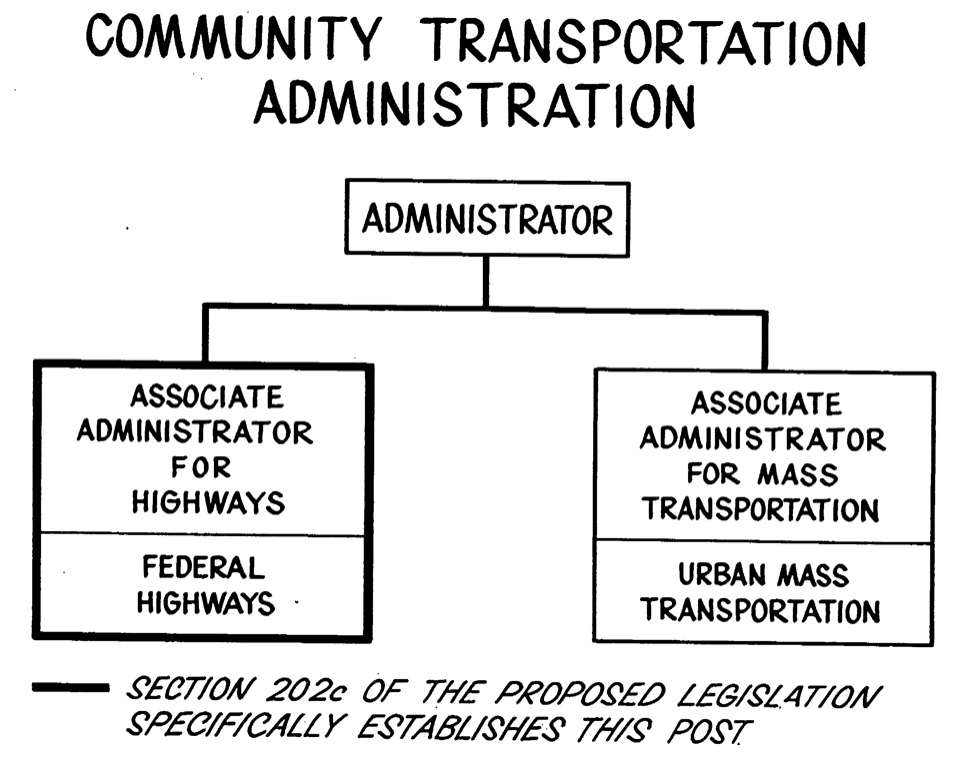

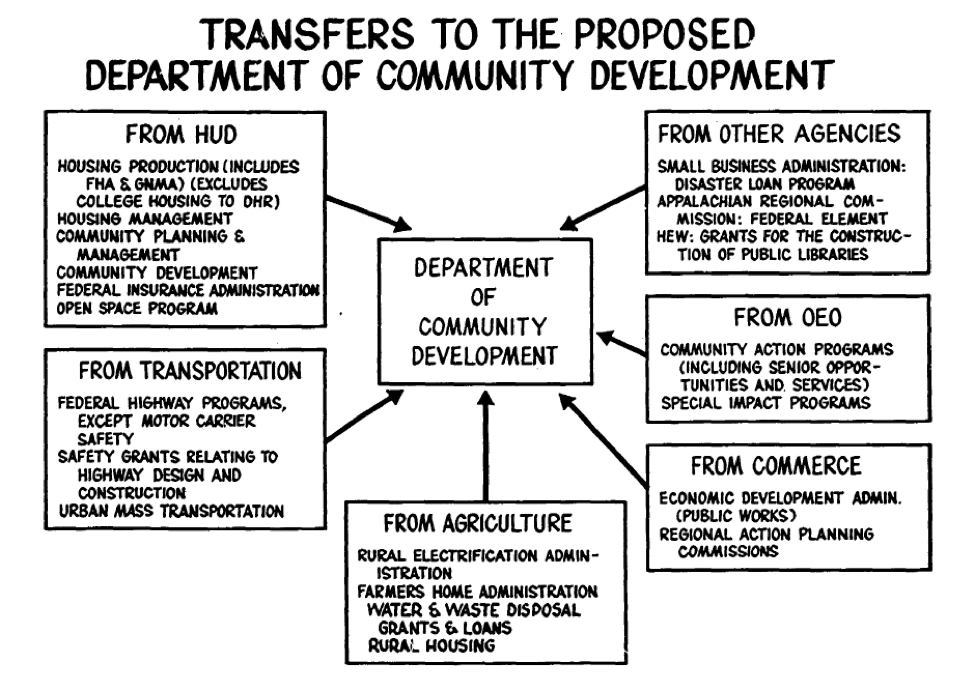

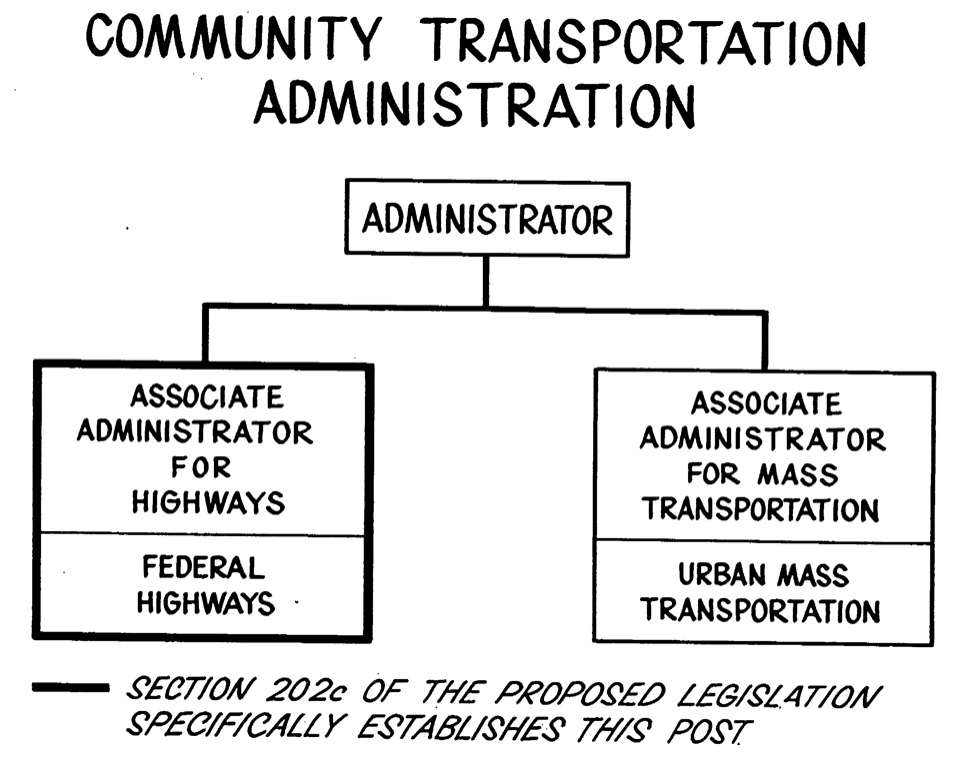

The proposal would have broken up the U.S. Department of Transportation, because the Nixon Administration viewed the provision and regulation of transportation as a function of what government does, not a fundamental goal that government should pursue in and of itself. The proposal would have put the Urban Mass Transportation Administration, the Federal Highway Administration (except for motor carrier safety regulation), and the highway safety grant functions of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in the Department of Community Development. They would have been placed within a new Community Transportation Administration at DCD.

DOT’s pipeline safety functions would have gone to the Department of Natural Resources. Everything else at DOT (the Federal Aviation Administration, the Federal Railroad, the Coast Guard, the St. Lawrence Seaway, and everything in the Office of the Secretary except the development of the supersonic transport plane (which was proposed to be sent to NASA) was judged to be part of the fundamental goal of enhancing interstate and foreign commerce and thus given to the Department of Economic Affairs, where they would have been placed in a new National Transportation Administration.

Office of Management and Budget Director George Shultz testified before the Senate Government Operations Committee two months later to explain the plan. He further amplified the basic philosophy: “the executive departments should be structured in conformance with basic goals or major purposes of government,, not service to a particular segment of the Nation’s citizenry or the performance of a particular function or process.”

The full White House justification and explanatory document for the Department of Community Development part of the proposal is here.

Overruling the Ash Council. Nixon’s proposed government reorganization was an offshoot of the President’s Advisory Council on Executive Organization, formed in April 1969 and headed by Roy L. Ash. Nixon, like Dwight Eisenhower, wanted a blue-ribbon panel of outsiders to perform their analysis of how the government should be organized. (Presidents Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson had used the Bureau of the Budget for that purpose, though Truman also paid attention to the outside Hoover Commission.)

The Ash Council’s initial recommendations over 1969-1970 were approved by the President and implemented using reorganization plans – the conversion of the Bureau of the Budget into the Office of Management and Budget and the establishment of the White House Domestic Policy Council (Plan No. 2 of 1970), the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (Plan No. 3 of 1970), and the creation of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Plan No. 4 of 1970).

White House domestic policy aide Ed Harper wrote in an academic journal article in 1996 that when Ash had presented the Council’s initial report on Cabinet reform to the President and his Cabinet, “The presentation seemed flat and uninspiring to ‘frigid’ cabinet members fearing they would lose some measure of policy control over their departments. The spindly gold plated chairs seemed particularly uncomfortable that afternoon…Hostile questions from several cabinet members, including Romney and Volpe, made it clear the plan was in trouble. But John Connally, the Lyndon Johnson Democrat who was a member of the Ash Council, came to the front of the room and gave a virtuoso performance and figuratively swept the meeting off its feet. In a dramatic and lively presentation, Connally translated Ash’s organization theories into political dynamics, explaining how he saw the reorganization to be politically beneficial to the cabinet members individually, to the president, and to the country.”

President Nixon’s March 1971 recommendations to Congress closely resembled the recommendations that the Ash Council made to the President throughout 1970 – with one glaring exception. As Shultz stated at the May 1971 Senate hearing:

I suppose the most obvious change is that in the current proposed reorganization, the President has included the Department of Transportation. The Ash Council did not do that –not because they thought it was a bad idea, but because they thought the Department of Transportation was outside their purview. Given the four new departments, as the President worked at reorganizing, the Department of Transportation was added to the consolidation effort. I think that is the most obvious change.

George Shultz, Senate testimony, May 25, 1971

(Irony alert: at the House and Senate hearings, Shultz was accompanied by several OMB staffers who helped produce the plan. Two of them were Alan Dean and Dwight Ink, who just three years beforehand had been the chief bureaucrats at DOT and HUD, respectively, and who had fought over, and later negotiated, the move of mass transit from HUD to DOT.)

Chairman Ash himself said at a House hearing the following month that “at the time we took up the work dealing with social and economic programs, the administration itself was considering transportation, the organization of transportation, and we defined that out of the analysis that we did. We did not come to a conclusion that it should be retained as a department. We did not consider what to do with the Department of Transportation…Because we felt it was an important function, an important means, and that the whole lifeblood of economic and business affairs depends upon transportation, we felt it should be an integral part of the Department of Economic Affairs, whose purpose is economic well-being. That is why the major thrust of transportation is in the Department of Economic Affairs. Urban mass transportation, having more close relationship to community development in contrast to major national economic affairs, we felt, should be a part of the Department of Community Development concerned with integrated and unified planning of individual communities. That aspect is more closely related to the community development function and less to total economic affairs, and so the line was drawn between the two.”

Charles Schultze, who had been head of the Bureau of the Budget under LBJ and who played a key role in the creation of DOT and the decision to eventually move mass transit from HUD to DOT, testified at the Senate hearings on May 26 and addressed the conceptual issue:

You are faced, I think, with one of the big, almost philosophical questions which this reorganization raises: Do all things of a transportation nature belong altogether or rather, should things which affect urban development be put together and things which affect economic affairs be put in another place? I come down, I think, after much soul searching, the same way the President does, that highways, particularly urban highways and urban mass transit, probably belong in community development. I do think that is one of the major substantive questions on which reasonable men might want to disagree, but I come down the same way he does.

-Charles Schultze, Senate testimony, May 26, 1971

In previous debates over highways and mass transit, much had been made of the original constitutional justification for the federal roads program (facilitation of interstate commerce, along with the ability to designate roads for postal traffic) versus no constitutional justification other than the general welfare clause for intrastate mass transit. The official White House summary of the plan justified transferring the entire highway program to the DCD, instead of the new Department charged with interstate commerce activities, this way: “The importance of the Interstate system to the American economy is recognized, but the system is basically in place and the remaining segments will have their greatest impact in communities.”

Secretary Romney explains. A full explanation of how the proposed Department of Community Development would work was later given to the House and Senate Committees in November 1971 by the Cabinet Secretary whose existing Department would form the basis of the proposed new Department: HUD Secretary George Romney, former governor of Michigan (and father of Mitt).

Romney told the Senate committee that as governor, he had consolidated 140 various state entities into just 19 departments and had also taken steps during his two years at HUD to reorganize and decentralize that department as well.

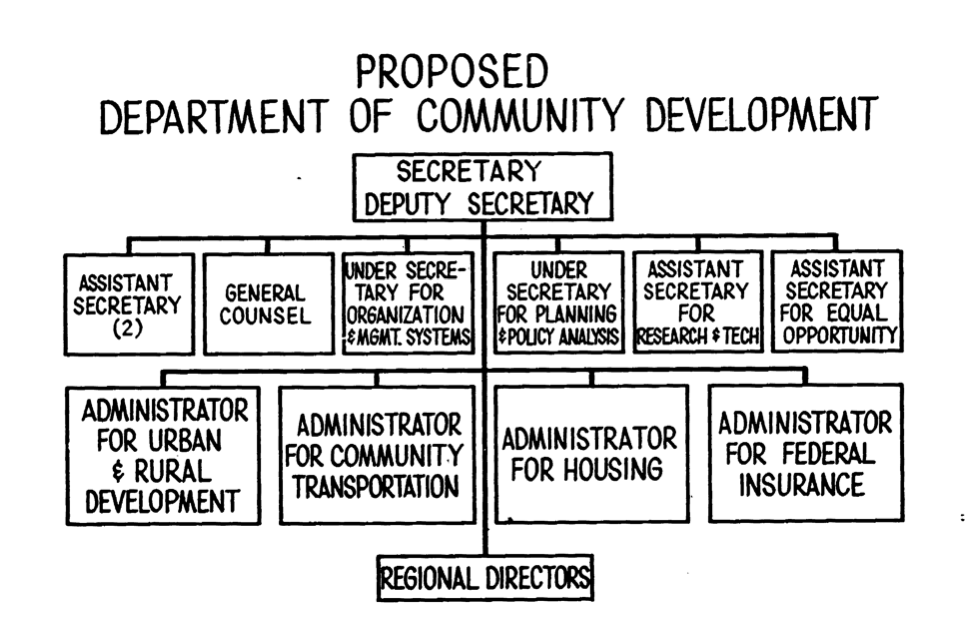

Romney defined the functions of the proposed DCD as being twofold: “One, to strengthen the institutional capacity of State and local governments, working with private business and civic organizations to solve community problems and meet community needs; and two, to assist them in carrying out urban and rural development, transportation, and housing programs. So basically, it would concern itself with the capacity of State and local and private organizations to plan what needs to be done at the community level and then to help them carry out the programs in the basic public facility and housing fields.”

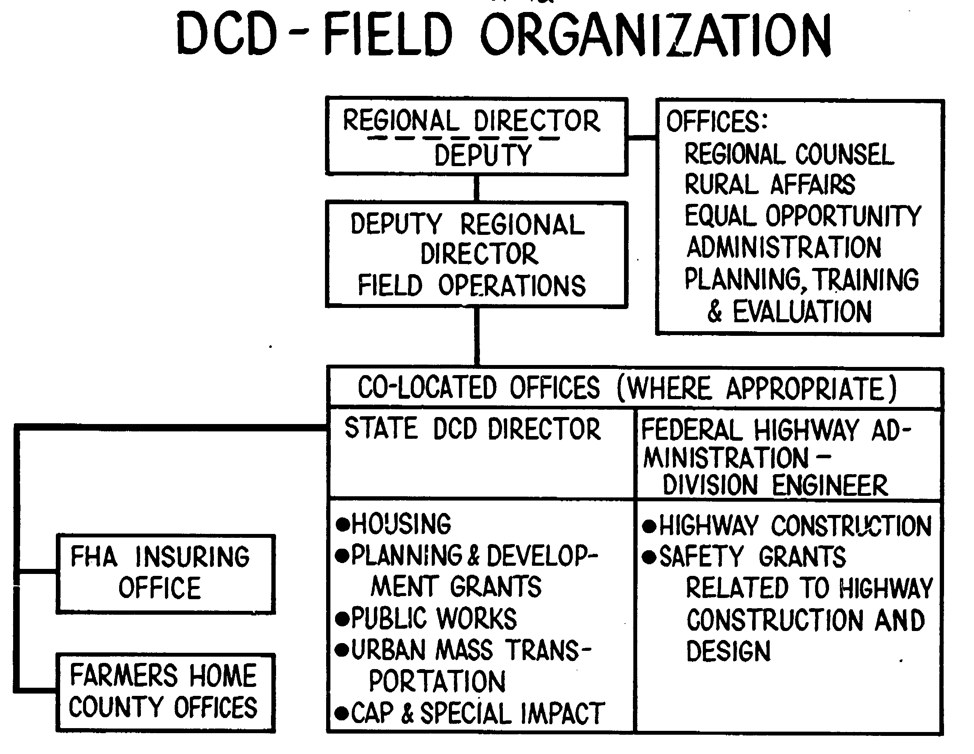

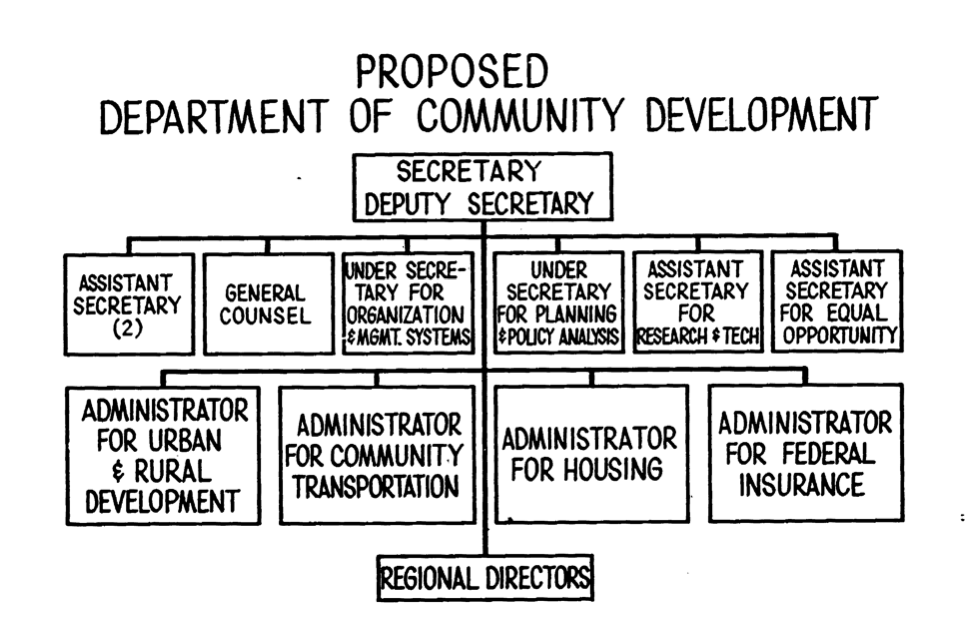

Romney came well-prepared and accompanied with a series of charts. These included an easy-to-view list of all the proposed DCD components:

As well as an proposed organizational chart:

FHWA and UMTA and the highway safety grants would be grouped together under the Administrator for Community Transportation. He pointed out to highway-focused legislators the steps that had been taken to treat the highway program differently: “ The position of Associate Administrator for Highways would be specified in the statute, which means that the highway program would continue to have a separate identity and supervision in the way it has had down through the years in the various departments in which it has been located. The highway program has been located in five different departments over the past 30 or 40 years and this would maintain a separate identity within the new department. But at the same time, it would bring it into a department where the most critical aspects of highway planning and development are now occurring; namely, in our communities. Consequently, we think this makes good sense.”

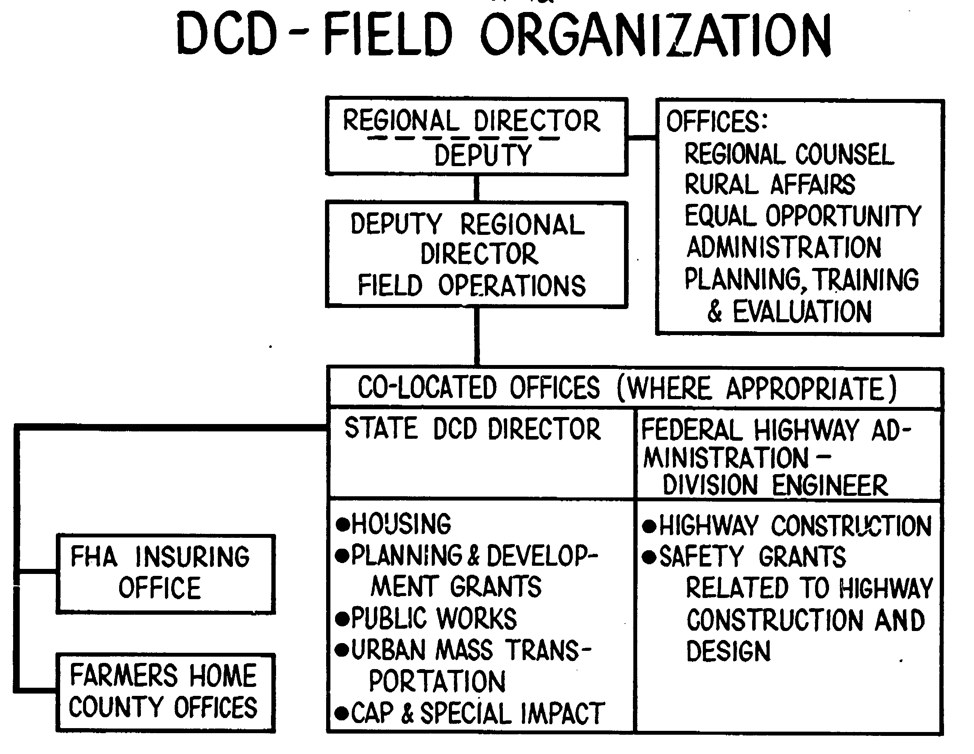

Romney also talked extensively about how the purpose of the plan was to locate as much of the Department’s personnel as possible in regional and state field offices in order to make them one-stop shops for federal community development assistance:

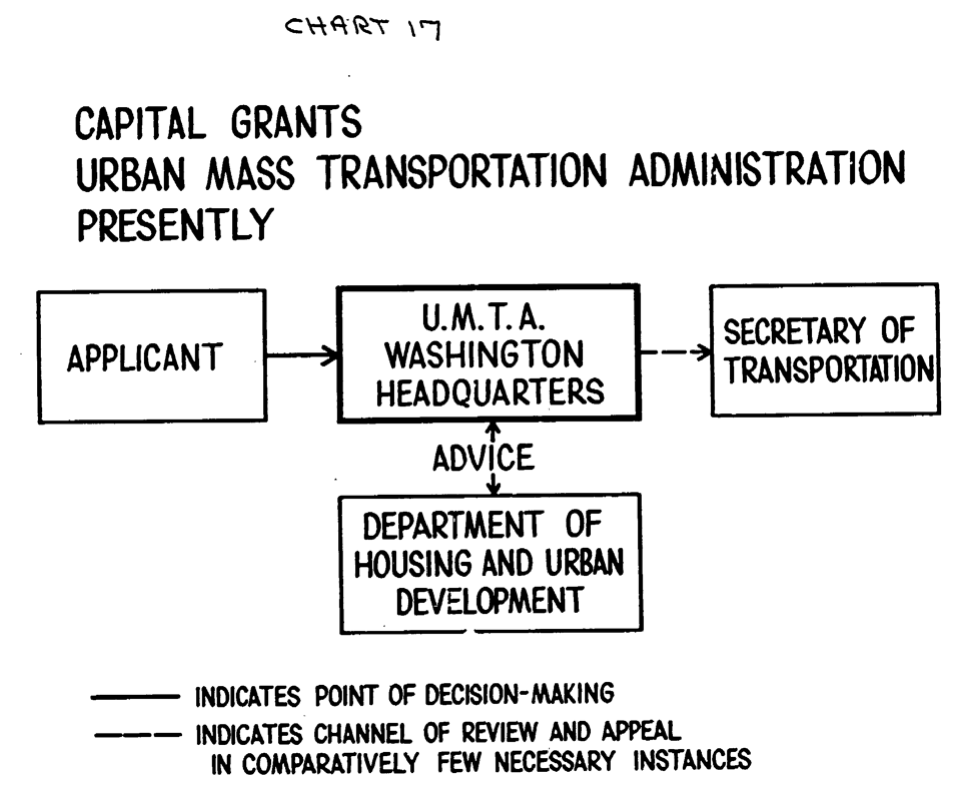

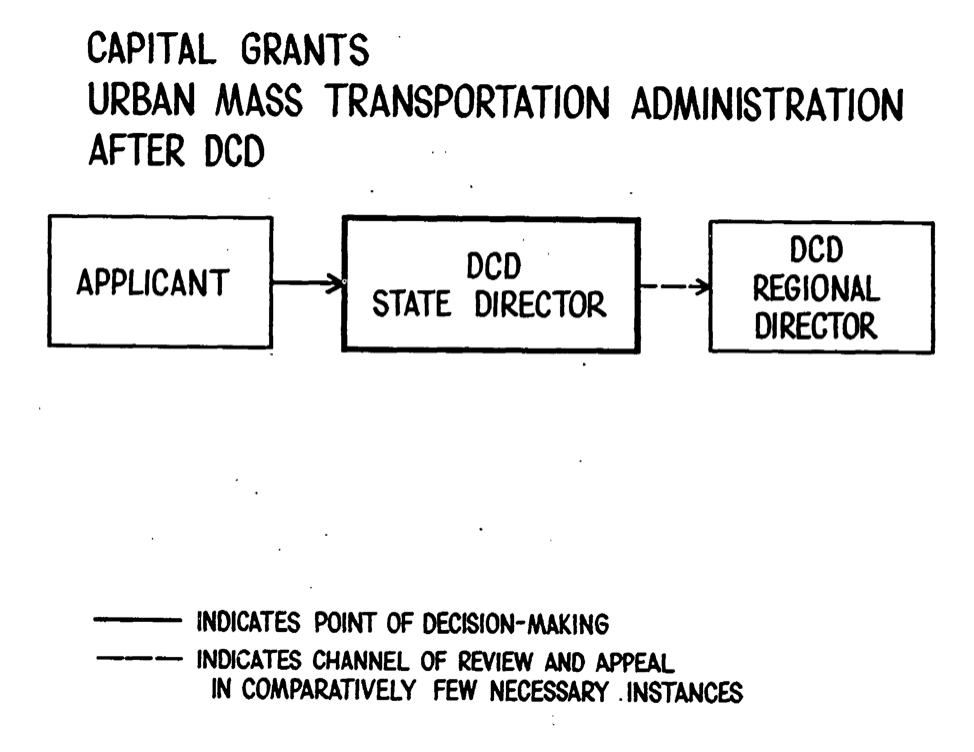

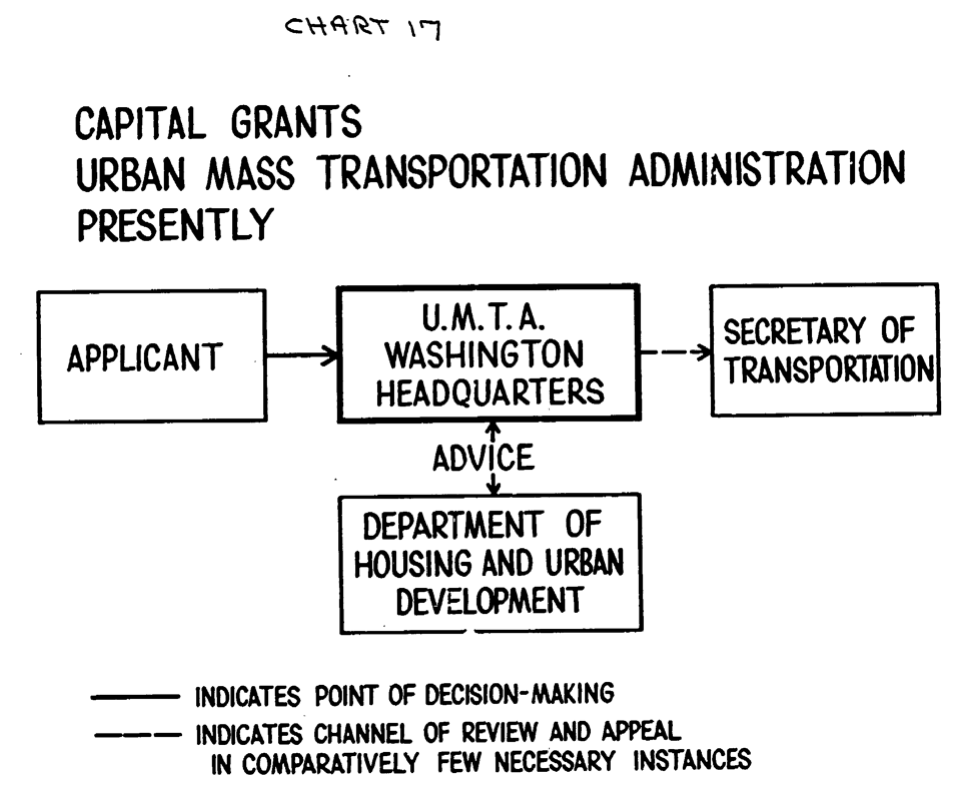

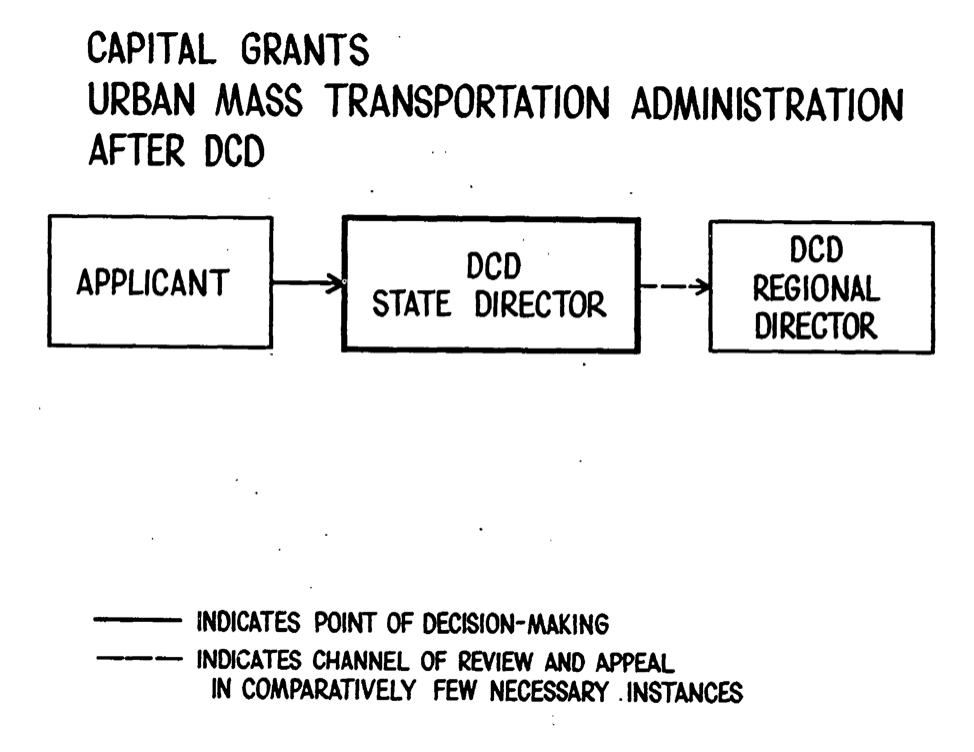

And while FHWA at that point already had division offices all over the U.S., UMTA did not – its activities and approvals were centralized in Washington, and decision-making in some instances was only made after consultation with HUD.

The new structure called for cutting Washington out of the equation in most instances:

At the various Senate and House hearings, the former HUD officials who had lost out on the mass transit move three years earlier spoke in favor of the new DCD. Former Under Secretary Robert Wood told the Senate panel that “…having lived through the establishment of HUD and DOT and then worked through those complicated relationships on mass transit, unless transportation is put in the new department and remains as proposed there, then this reorganization plan will be hardly worth the effort… Of the 30,000 or 40,000 miles of the Interstate Highway System, the mileage remaining has to be built in the great metropolitan areas. They have to come to terms with those politics; they can only do it within HUD.”

Former HUD Secretary Robert Weaver told the House panel that he agreed: “ The return of mass transportation to the department concerned with planning, community development and housing is an excellent idea. And, now that the Interstate Highway System is nearing completion and having its major impact upon urban communities, it is appropriate to locate it with mass transportation. Out of the merger a desirable mix between the two and a consistent impact upon planning and development can be achieved.”

(Weaver was also critical of the decentralization that was part of the plan, saying that “ if you get all of this decentralization, you are going to get into great difficulty, you are going to place a guy out there who is under the thumb of a strong mayor in a very, very difficult position. And he is going to be the first one to holler and say, please, take it back.”)

Secretary Volpe justifies the plan. It is easy for current and former officials at the existing bureaucracy, which looks to be completely victorious in an internal turf war by greatly adding to its jurisdiction, to be supportive of the proposal. It is quite another thing to see the losers of the struggle put on a happy face and try to sell the proposal.

Transportation Secretary John Volpe was interviewed by a senior official of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in an interview broadcast over national radio in July 1971:

QUESTION: Secretary Volpe, the Department of Transportation is five years old, having been created in 1966 for the purpose of putting all of the government’s transportation-related programs under one roof. But just at a time when the Department is coming into its own, it may be dissolved in favor of a new, goal-oriented reorganization plan. How does the now plan look to you?

MR. VOLPE: Well, I would rather think of it in terms of placing the Department in two of the new departments — primarily in the Department of Economic Affairs where it will actually be a part of the total economic picture of the nation. Lot’s fact it, transportation – too frequently in the past — has progressed without looking at the total economic picture. We should determine where the hospital is going to be built in the future, or where the new university is going to be built, or where more schools are going to be built, or where the factories are going to be built, and then build transportation around these things. By being primarily in the Department of Economic Affairs, with two of the components being placed in the Department of Community Development, I think we’ll be able to exert even more force than we do now because we’ll be in a department where the real economic decisions of the nation will be made…

…Some people have said that because we have interstate highways, we can’t justify having the Highway Administration in the Department of Community Development. The fact is that the interstate system is the only highway program that is truly national in character. It is due for completion about 1977 or 1978. Highway programs from then on will be primarily community-oriented….

QUESTION: How do you see mass transit and highway programs as being properly related?

MR. VOLPE: Well, they will be properly related because they’ll both be in the Department of Community Development. I would imagine — although this hasn’t been frozen in concrete — that there will probably be an administration for community transportation; just as my Federal Highway Administration and my Urban Mass Transit Administration work very closely within my department, I’m sure they’ll be working very, very closely in the new Department of Community Development. I hope that more and more highways will be used for public transportation. This Shirley Highway experiment we’ve had here in Washington, and four or five others across the nation, are showing that if people are given a viable alternative — people who only go from their home to their work each day and back — they will use good bus transportation. I don’t mean the buses of forty years ago – fuming, noisy, and clattering — I mean the new buses that are carpeted, air-conditioned, have pastel colors and comfortable seats, and have no jerking in the operation. I think having both urban mass, which provides the buses, and the highway department together will serve very well.

-Transportation Secretary John Volpe, July 1971

The initial overview hearings in the House and Senate revealed a consensus that of the four proposed new departments, the Department of Community Development made the most sense and would be the easiest to enact. Accordingly, House Government Operations chairman Chet Holifield (D-CA), who had been the lead House sponsor of the bill creating DOT five years previously, held an astounding sixteen days of hearingson the Department of Community Development proposal over 1971-1972.

On November 9, 1971, Secretary Volpe testified before the House panel (with Alan Dean sitting next to him to make sure he stayed on-message). He said “I am supporting a division of transportation functions essentially between two departments based on their primarily national versus predominantly local orientations.” He also said that the White House had reconsidered the earlier part of the plan that would have split up NHTSA and was not supporting a transfer of all of NHTSA’s activities (highway safety grants and vehicle safety regulation) to the Department of Economic Affairs.

Volpe also emphasized the continuity that stakeholders would experience: “ great care is being taken to preserve the effective delivery systems currently existing. The State highway departments, for instance, will continue to conduct their business with the division engineers in their States as at the present. Similarly, only one Federal agency will be concerned with mass transit grants. I am confident that the clientele groups and planning agencies will find their tasks facilitated by the new organization, since the community planning and development agencies will also be in the same single Department.”

And he also addressed the 800-pound gorilla that usually torpedoed major efforts to reshape the government: “I would like to add just one point which I have personally discussed with President Nixon and which he wished me to emphasize. It should be clear that enactment of this bill would not in any way require any changes in the jurisdiction of the congressional committees. Only Congress should, and can, determine the changes, if any, that may be necessary. If there are to be changes, the Congress will make this decision. So far as we are concerned, this is the responsibility of the Congress and not of the executive branch.”

Volpe also summed up the function-versus-goal framework governing the overall Nixon plan in a pithy way that was somewhat astonishing for a Secretary of Transportation:

Transportation, in and of itself, really does not mean a thing. It is what it does for people that really counts. “Yes; we do have an emerging battle in sight.” You might say we have a battle in sight. The question is who is going to get the bigger part of the transportation dollar. Today, highways are getting the bigger part of that dollar, but that might change.

The fact is, however, that we have a real catchup job to do in mass transportation, and I think it is incumbent upon the administration and the Congress to come to grips with this. I think we can come to grips with it more handily and more efficiently if we have a single administrator in charge of these two transportation agencies within the Department of Community Development, rather than have them as separate administrations, as they are now.

-Transportation Secretary John Volpe, November 1971

In response to questioning, Volpe also admitted that “having one man responsible for both mass and highway transportation will place him in a position of coming up with a coordinated budget and perhaps in helping to fashion a more balanced system than is presently the case” and agreed that this would make a good case to Congress to allow Highway Trust Fund money to be used for mass transit in some instances.

The highway lobby opposes. Of course, with sixteen days of hearings, not all of the testimony was positive. The highway lobby, in the form of the leadership of the American Association of State Highway Officials, testified in March 1972. AASHO president J.C. Dingwall told the committee that they had had Alan Dean come to their annual meeting in December 1971 to explain the plan and that “I think that Mr. Dean did an excellent job of his explanation but the proposal did not sell, at least not that group.”

Dingwall said that the state highway departments had later adopted a policy resolution stating that they “oppose any move which would fragment the Federal Highway Administration out of the DOT, so to speak, and put it in an area that they felt was totally unrelated to national highway objectives.”

He then made one of the definitive state highway department arguments about urban transportation issues:

I would like to make just one comment on this urban sprawl business on which there has been a rather unsavory connotation placed on the word “sprawl.”

People have gone out into these areas away from central city because they wanted to, nobody had forced them out there. It is more attractive, they get a little more room for their children to play, and as long as a man wants his freedom of movement, and wants to move out into the suburban area, we think he ought to have that freedom and that not only us, but the Federal agencies involved ought to cooperate with those people who choose that way of living.

We hear a great deal about the highway program paving over the country with asphalt and concrete. Actually a little over 1 percent of the land area is involved in the highway system rights of way of this country, and it is approximately 30 percent of the land area, in the urban areas that is taken up by roads, streets, alleys, and so forth. This is essential for adequate accessibility and mobility for such population and land use densities.

With respect to the part of the country and the amount of the country these highways touch as compared with other modes of transportation, in order to say with our point that highways are national in scope and must be kept national in scope and never confined to what we have termed a community…highways are national in scope and what is done with them should not be placed in with any agency that might have, or section of an agency that might have totally unrelated interests to the highway business.

-AASHO President J.C. Dingwall, March 1972

On March 27, the Associated General Contractors testified before Holifield’s panel. Their Senior VP, Nello Teer, asked “Why should highway transportation be subordinated to housing? The need for a balanced transportation system has been cited as a prerequisite to community development, but without coordination between Federal participation in all modes of travel, we would be creating the same problems in transportation which existed prior to the creation of the Department of Transportation. Planning for coordination of travel involving some communities which depend on rail and air transportation as much as highways would again dilute and defeat the efforts of consolidation.”

One of the members of the House Government Operations Committee was Rep. Jim Wright (D-TX), who was also a high ranking member of the Public Works Committee and a big-time highway advocate. Wright got Teer to agree with his leading question “In other words, about 7 percent of the mileage in the highway network is primarily devoted to urban nee(s within the cities, and approximately 93 percent is devoted to moving people nationally and regionally between the cities. Doesn’t it seem logical, then, that 93 percent being devoted to transportation between cities would qualify that function for the Department of Transportation? If we were to place the responsibility in the Department of Community Development, where only 7 percent of the highway mileage is functionally related, wouldn’t the tail be wagging the dog?”

The bill is reported. Through Holifield’s dogged leadership, the bill creating the Department of Community Development (H.R. 6962, 92ndCongress) was actually marked up and approved in subcommittee in the House on May 4, 1972 (Holifield chaired the subcommittee as well) and in the full Government Operations Committee on May 10. The final vote was 27 to 7, with one member voting “present.” The committee made one major change to the bill – instead of establishing an Urban and Rural Development Administration within the Department, the reported bill established separate Administrations for Urban Development and for Rural Development.

But the committee’s report (H. Rept. 92-1096) also indicated that deep divisions on the bill that indicated significant opposition. There were six different sets of additional, dissenting and minority views filed with the report. Wright filed his own additional views opposing the FHWA move, and Wright, future Public Works chairman Bob Jones (D-AL), and two other members filed additional views opposing the moves of both FHWA and the Economic Development Administration.

Four liberals on the panel filed additional views opposing the bill because it would “result in the emasculation of the Office of Economic Opportunity and in the disappearance of the government’s separately identifiable commitment to end poverty in our generation.” Six members of the panel filed minority views stating “there may be areas within the Department which should be reorganized. However, once dismantling of the Department of Agriculture begins, it will accelerate at an alarming rate. It could be the beginning of the end.”

And future GovOps chairman Jack Brooks (D-TX) filed his own views denying the validity of the President’s overall organization theme: “The President’s reorganization plan calls for fewer, larger departments, organized on the basis of objective rather than function, supported by the concept that organization, rather than capable leadership and adequate resources, is the key to efficient operation. Yet, a stronger case can be made for a larger number of smaller agencies organized on the basis of function, recognizing that capability of leadership and adequacy of resources constitute the most critical factors in the efficiency and effectiveness of the organization’s operations.”

The committee filed its report on the bill in the House on May 25, 1972, and that is as far as it went. With so many different interest groups and House committee chairmen fighting to preserve the status quo, the House Rules Committee never considered the bill, and the House Democratic leadership did not force their hand. None of the other bills implementing the proposed Cabinet restructuring were ever reported from committee in the House or Senate, and Nixon did not make the proposal anew in his second term.

[To be continued with discussions of how the House, but not the Senate, came to view transportation as a unified policy under the purview of a single committee, and of whatever happened to all that DOT-HUD cooperation promised in 1968.]