What’s the Purpose of Mass Transit? – Part 2

July 6, 2018

This week marks the 50th anniversary of the transfer of federal responsibility for mass transit from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to the Department of Transportation. This has prompted the author to finish a long-gestating research project on the history of the debate over whether or not mass transit is more about transportation or more about urban development and land use. Part one of the series, from last week, can be read here and took us to December 1962, where a mass transit bill had failed in Congress and transit advocates were trying to regroup.

1963 – Williams and the White House try again. Transit advocates and their leader Sen. Pete Williams (D-NJ) wanted to open the 88th Congress with having the mass transit bill introduced in the Senate on Opening Day with bill number S. 1 for status reasons. Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-MT) wouldn’t give them the #1 slot, but the transit bill was introduced on January 14 by Williams and 20 cosponsors as S. 6.

The bill provided $500 million in contract authority for the grant programs, contrary to the White House’s wishes. President Kennedy on February 18 sent Congress his own proposed transit bill (S. 917, 88th Congress), largely similar to the Williams bill but with the $500 million as a simple authorization subject to subsequent Appropriations Committee action.

And whatever behind-the-scenes negotiations had taken place on the jurisdictional issue – Banking Committee versus Commerce Committee – had apparently been successful. In his remarks upon introducing the bill (see p. 214 here), Williams said that if the transit bill’s chief opponent from the Commerce Committee, Frank Lausche (D-OH), “had been on the floor at this time, he would have indicated his acquiescence in having the bill referred to Banking and Currency, and that at a later time he would suggest that the Commerce Committee has an appropriate interest in the bill, too.”

Some of this may have been due to pressure placed on Senate Commerce Committee chairman Warren Magnuson (D-WA). At a closed-door meeting of transit interests in mid-December 1962, the group had decided that they should try to orchestrate “expressions of opposition to Commerce jurisdiction by mayors, public officials, and industry people in the State of Washington to Senator Magnuson.”

This was apparently effective. The Banking Committee started holding hearings on the bill on February 26, and at the March 4 hearing, Chairman Magnuson showed up in tow with the Mayor of Seattle, who was to testify. The following is an exchange between Magnuson and Banking members Paul Douglas (D-IL) and John Sparkman (D-AL):

An internal memo in the White House legislative affairs office from Senate lobbyist Mike Manatos the following week summed up the situation: “Senators Lausche and Thurmond (and to some extent Engle) want Mass Transit referred to the Commerce Committee. Magnuson tells me that if the Committee will back him up he will resist any such motion as he testified before the Banking Committee last week, he was the one who suggested the bill be referred to Banking in the first place. Magnuson will fold unless reinforced, and I think Pastore would be ideal if he were willing to support Magnuson. Everyone agrees Lausche wants to kill the bill, as does Thurmond. Engle happens to believe the bill would have a better chance if two committees reported it.” (Emphasis added. Manatos also referred to Sens. Clair Engle (D-CA) and John Pastore (D-RI), both of whom were Commerce members – Pastore was the ranking Democrat behind Magnuson.)

The memo also reveals that the vote count on the transit bill in the Banking Committee was rather close – seven in favor (Sparkman, Douglas, Clark (D-PA), Williams, Long (D-MO), Neuberger (D-OR), and Javits (R-NY)) and six opposed (Robertson (D-VA), Proxmire (D-WI), Bennett (R-UT), Tower (R-TX), Simpson (R-WY), and Dominick (R-CO)) with two members undecided – Ed Muskie (D-ME) and Thomas McIntyre (D-NH). Manatos wrote that “Muskie has no ‘philosophical’ problem with Rapid Transit, having supported the bill last year, but he feels that somewhere along the line he must establish an image of budget consciousness for 1964 with result to new programs. Muskie is the key vote on the Committee because he would take along with him Senator McIntyre…”

The Banking Committee finished its full committee markup of the bill the following day (March 14) and indeed it went just as Manatos had predicted – the vote count in the committee was seven in favor and six opposed, and then Muskie and McIntyre said that they were opposed to the bill and were going to vote “no” on the Senate floor, but would nonetheless vote “yes” in committee. So what could have been a seven aye, eight no defeat became a nine aye, six no victory for the transit bill.

During the markup, Javits told Williams that while he was with Williams on keeping the main funding in the bill contract authority and not a subject-to-annual-appropriations authorization, he wondered if acceding to the Administration position (and also the House position) against contract authority wouldn’t be “the best thing for the bill.” Williams responded:

I am so convinced that merit and wisdom are on the side of contract authority, because what we are contracting for is construction, improvement of facilities, where the work will require more than one year. It is designed to stimulate local spending. And this means local borrowing in the private market.

And private lenders have to have, they tell us, the assurance that if they are going to lend for a five-year construction program and the Federal Government is part of it that the Federal Government won’t stop its contribution when the bridge is half built.

So I feel all wisdom is on the side of contracts. I certainly am aware of the political facts of life. If there is to be capitulation on this, I would think it shouldn’t be now but only after we have seen the whites of the eyes of the enemy, to rephrase Brigham Young’s statement.

-Sen. Pete Williams, March 1963

(John Tower did offer an amendment to strike the $500 million in contract authority and replace it with $500 million in authorizations, which failed on a six-six tie in a show of hands.)

The bill was reported to the Senate on the day of the committee vote, and did contain some amendments recommended by Banking, some of which were to address Commerce Committee concerns. But when filing the bill, Williams also asked unanimous consent that the Commerce Committee then be granted custody of the bill until no later than midnight on March 28, which was agreed to (see page 4142 here).

Lausche had introduced his own transit bill (S. 807, 88th Congress) that took responsibility for mass transit away from HHFA and placed it in the Commerce Department, in a new Division of Urban Transportation that would answer to the Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation. But instead of providing funding for federal grants to be made directly to transit systems, the Lausche bill proposed a new system by which the federal government would guarantee the revenue bonds issued by local transit agencies (public or private). The bill as introduced would also have added tax breaks for local transit agencies, which threatened to cause subsequent referral to the Finance Committee.

Commerce held four days of hearings on all three bills (S. 6, S. 807, and S. 917), chaired by Transportation Subcommittee chairman Strom Thurmond (D-SC), who questioned HHFA head Robert Weaver extensively. Weaver, on behalf of the Kennedy Administration, opposed Lausche’s bill, not just because it would move mass transit out of his agency, but because federal guarantees of tax-exempt municipal debt were against longstanding Treasury policy. Also, Weaver said that the Lausche bill would only help the largest cities that were trying to construct “new start” rail systems, whereas the Administration’s program would provide support to a broader range of cities.

Thurmond pressed Weaver hard as to what justification under the Constitution the federal government could claim for providing direct aid to cities for mass transit. Weaver responded with a statement for the record that cited extensive Supreme Court precedents under the Spending and General Welfare clauses, culminating in this summary:

…the following conclusions may properly be drawn with respect to the constitutionality of proposed legislation to aid mass transportation:

(1) Congress possesses a substantive power to provide and appropriate funds for the general welfare of the United States, distinct from other express powers granted under the Constitution.

(2) The determination of what action is appropriate to provide for the general welfare is essentially a matter within the discretion of the Congress.

(3) Should Congress determine that the provision, improvement, or extension of mass transportation systems in the various States and localities is of such concern to the Nation as a whole as to require Federal action, legislation enacted for that purpose could not successfully be challenged, under existing judicial precedent, as being in excess of the power specifically granted under the Constitution to provide for the general welfare of the United States.

-HHFA submission to the Senate Commerce Committee, March 1963

The mass transit bill was a Democratic leadership priority and was part of President Kennedy’s agenda. The Commerce Committee at this time was particularly stacked in favor of Democrats (twelve majority seats to just five Republicans). Accordingly, the votes were not there to kill the bill outright, but at the same time, they had to assert their jurisdiction somehow. Thurmond’s subcommittee adopted five amendments to S. 6 which were then folded into a substitute amendment recommended by the full committee in its report.

Most importantly, Commerce replaced the $500 million in contract authority recommended by Banking with $375 million in authorizations subject to future appropriation, and they added the revenue bond provision from Lausche’s bill. But they did not move the transit program to the Commerce Department – they left it at HHFA, albeit with new requirements that HHFA consult with the ICC on rail projects, require transit agencies to charge “economically sound” fares, and refuse to bail out private transit companies unless local governments had first tried giving them tax relief.

Several Commerce members were still opposed to the bill, but they agreed to try and kill it on the Senate floor, not in committee.

Williams’ staff had worked with transit interest groups to come up with a full Senate vote count dated March 6, 1963. That vote count had shown 58 Senators committed or leaning towards supporting the bill on final passage, and 54 Senators supporting or leaning towards Williams’ position on contract authority.

Banking and Commerce both filed their reports on the night of Thursday, March 28, and the Senate took up the bill on Monday, April 1 and made it the pending business of the Senate. When debate began in earnest on April 2, Sparkman moved that the Senate adopt the amendments recommended by the Banking Committee, which was done, and then Engle moved to substitute the Commerce-recommended bill for the version just amended, which was also done by unanimous consent. So the contract authority fight was over before it began in earnest, and contract authority was removed from the Senate bill.

Initial debate on the floor focused on the labor provisions of the bill (outside the scope of this article but of major import). But on the following day, April 3, Lausche offered an amendment to move the mass transit program from HHFA to the Commerce Department and establish it in a new Division of Urban Transportation there (see here starting on p. 5594).

Lausche said “In the Department of Commerce there is already a Division dealing with transportation. The fact that in the Department of Commerce there are divisions dealing with every one of the modes of transportation; that is, pipeline, truck line, railroad, rail line, inland waterway, and so forth. This Division would be established in the Department, and most of the personnel it now has could be coordinated into doing this one job. We could definitely, in my opinion, streamline this matter better by having all of the functions in one department than by having them in two departments.”

Sen. Williams responded “The Agency administering this existing program has been able to capably administer the existing program, not with a division, not a battalion, not a regiment, but an office of transportation. It is my understanding that there are employees there, perhaps 20, but I believe less than 20. I would suggest to my friend, who is so admirably prudent with the taxpayer’s dollar, that I believe we can approach this really national problem far better than he suggests…”

Williams closed with a specific reference to holistic urban needs:

…the oneness of this is that in urban areas all Federal programs have a relationship one to the other.

If these programs are now administered by the Housing and Home Finance Agency, as they are, it would bea desperate mistake to take from them the opportunity to weave the circulatory system of transportation system into other urban areas concerned.

-Sen. Pete Williams, April 3, 1963

The Senate rejected Lausche’s amendment by a margin of almost two to one – 33 yeas to 62 nays (p. 5606 here). The following day (April 4), the Senate passed the amended bill by a vote of 52 yeas, 41 nays (p. 5688 here).

The House Banking Committee had ordered its version of the transit bill (H.R. 3881, 88th Congress) reported on March 28 by a vote of 22 to 7. But the labor protections that the AFL-CIO was insisting on had drawn serious opposition from the President’s economic team – the White House Budget Director and the head of the Council of Economic Advisers wrote to the President on May 28 that “if this portion of the bill cannot be made acceptable perhaps it should be allowed to die.”

(Remember that at this time, most mass transit (rail and bus) was privately owned, and many rail transit employees were covered by the extremely strong labor protections negotiated by rail unions over the previous 80 years – but public employee unions, in the few places they existed, were very weak. So the prospect of local governments taking over mass transit operations could have meant stripping existing mass transit workers of their contractual protections and benefits. The AFL-CIO had drawn a line in the sand in early 1963 to say this could not be allowed to happen.)

Between the labor problems and the general hostility of rural conservatives towards big cities in general and towards a potentially massive new federal program in particular, House leaders did not see a path towards getting the necessary 218 votes to pass the mass transit bill, so no effort was made to get a rule from the Rules Committee and take the bill to the floor.

Mass transit appeared dead in the House of Representatives. Until the events of November 22.

1964 – LBJ completes the Kennedy agenda. After President Kennedy’s assassination, Lyndon Johnson quickly decided to take whatever momentum he had and use it to get as much of the White House’s pending agenda for the 88th Congress enacted as possible. The story has been told repeatedly in history books and in two recent motion pictures. But while the main story revolves around Kennedy’s civil rights bill that was given up for dead in 1963 but somehow pulled through Congress by Johnson in 1964, there were a great many other items on that agenda as well, including mass transit.

A month before Kennedy’s assassination, the mass transit bill did not show up on senior Kennedy aide Ted Sorenson’s list of priority bills for the remainder of the Congress. As late as February 6, 1964, the White House’s liaison to the House of Representatives, Henry Wilson, was telling his colleagues that “I regard Mass Transit as dead on the floor.” The head of legislative liaison, Larry O’Brien, sent a memo to President Johnson the following day that said “We do not have the votes on the floor to pass Mass Transit without a massive effort, and we are just not in shape to tackle it yet.”

On February 20, transit lobbyists reported to the White House that their own vote count showed a total of 172 certain “yes” votes and another 50 leaning “yes” votes, which would be a total of a bare majority of 222, but White House staff dismissed this as being overly optimistic, particularly because it assumed 32 Republican “yes” votes.

But the White House continued to lobby, slowly – hear a May 20 audio recording of President Johnson and Larry O’Brien on the vote count at the 3:30 mark here). On May 21, the Rules Committee actually issued a rule allowing the transit bill to come before the House for open debate. But the Speaker and Majority Leader were not going to bring it to the floor without a solid vote count. On May 28, the White House staff reported a vote count of 189 “yes” votes and another 33 leaning “yes,” which again got to 222, which was just barely over the magic 218 mark, but they were still afraid to move the bill before the leaning “yes” votes had firmed up into solid support.

On the following day (May 29), Wilson had a different idea. As he wrote to Larry O’Brien on June 1, he thought that they needed to expand their lobbying coalition of private interest groups beyond cities, railroads, and mass transit companies, so:

O’Brien and President Johnson discussed the vote count on June 12 and agreed that while the situation was improving to “reasonable shape” the bill was not quite ready for the floor – they needed another ten votes. By June 22, Wilson was reporting that he “counted 175 Democrats” in support of the mass transit bill. Together with an estimated 40 Republicans, plus others from both parties who might be persuaded, this was good enough for the Speaker to allow the bill to be called up for debate in the House on June 24. After amendment and debate (almost none of which focused on whether mass transit belonged at HHFA or at Commerce), the House passed H.R. 3881 as amended on June 25 by a very narrow margin of 212 yeas, 189 nays, with three members voting “present” (see p. 14986 here and hear an audio recording of LBJ being notified of the vote result here.).

The House then amended S. 6 with the text of the bill just passed by the House and passed S. 6 by voice vote. While there were differences in the House and Senate bills (listed on page 15463 here), particularly on labor protection and a Buy America provision in the House bill that was getting strong pushback from the State Department, Senate leaders (at the behest of the White House) decided to just take the House bill rather than risk a House-Senate conference committee that might produce a final work product that could not pass the House. In the words of Majority Leader Mansfield:

…as one who has followed this subject fairly closely in the leadership position, and who knows something of the difficulties that were encountered in the House, I merely say that based on the information that was available to me last Wednesday, I believe that something in the nature of a miracle has occurred to get this bill through the House.

If we want a mass transit bill, we will, in my opinion, take the House bill; otherwise we shall have no transit bill at all.

-Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, June 30, 1964

The Senate then agreed to the House-passed bill by a tepid vote of 47 yeas, 36 nays, with 17 not voting.

While Sen. Lausche voted against the bill and lost, he did say something in his closing remarks against the legislation that have turned out to be 100 percent accurate: “In my judgment, if we pass the bill, the Federal Government will forever be in the field of providing moneys with which to buy buses, equipment, parking facilities and other needs of local mass transportation systems.”

President Johnson then signed the bill into law on July 9 (but only after some internal back-and-forth on the Buy America issue – see the White House enrolled bill file here).

Congress had committed to an ongoing role in mass transit, and had confirmed that it belonged with other urban development programs at HHFA. But HHFA was not long to continue under that name.

Creation of HUD. The idea that the problems of urban America were so distinct as to deserve their own Cabinet-level department were first expressed in Congress by freshman J. Arthur Younger (R-CA) in 1954 when he introduced legislation (H.R. 10032, 83rd Congress) to create a new “Department of Urbiculture.” In his introductory remarks, Younger said that “many of our urban problems originate from our faulty techniques in the development and use of urban real estate” and hoped that a Cabinet-level Urbiculture Department could do for cities what the Agriculture Department had done for rural America.

Younger re-introduced his bill the following year (as H.R. 1864, 84th Congress) and it actually got a hearing in the House Government Operations Committee on July 26, 1955, but nothing else ever came of it. At the hearing, Younger admitted that “I am not naive enough to believe that a bill of this character can be speedily passed in the Congress…However, I am convinced that a bill of this type sometime will be passed, and a department as authorized by this bill will be created. It may be 8 or 10 years from now.”

Six years later, in the same March 1961 special message to Congress in which he ordered a joint Commerce-HHFA study on urban mass transportation needs, President Kennedy endorsed the general proposal:

Urban and suburban areas now contain the overwhelming majority of our population, and a preponderance of our industrial, commercial and educational resources. The programs outlined above, as well as existing housing and community development programs, deserve the best possible administrative efficiency, stature and role in the councils of the Federal Government. An awareness of these problems and programs should be constantly brought to the Cabinet table, and coordinated leadership provided for functions related to urban affairs but appropriately performed by a variety of Departments and agencies.

I therefore recommend–and shall shortly offer a suggested proposal for–the establishment in the Executive Branch of a new, Cabinet-rank Department of Housing and Urban Affairs.

-John F. Kennedy, March 1961

The White House sent a draft bill to Congress on April 18 (introduced as H.R. 6433 and S. 1633, 87th Congress), and it got hearings in the House and Senate and was reported favorably out of committee in both chambers in August and September 1961, respectively. But it never got debate in either chamber – in the House, the conservative-dominated Rules Committee refused to give it a rule, and in the Senate, there seemed to be no point since the House would not act. Part of this was due to opposition from state governments who did not want to lose authority over the cities under their jurisdiction. A June 1961 letter from the bipartisan Advisory Council on Intergovernmental Relations said that “the Commission strongly recommends that if a department is established, its relationships with State and local governments be so conducted as to encourage the legitimate and necessary role of the States with respect to urban problems.”

Undaunted, Kennedy tried another approach the following year, submitting a reorganization plan to Congress in January 1962 to create the same Department that the legislation of the previous year would have created. Under the Reorganization Act of 1949, Presidents could submit reorganization plans to consolidate agencies and otherwise rearrange the deck chairs of government, and such plans would automatically take effect unless either chamber of Congress voted to disapprove the plan within certain period of time. (Such “legislative veto” provisions were ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark 1982 INS v. Chadha decision.)

On the same day that Kennedy’s reorganization plan was received by Congress, Rep. George Meader (R-MI) introduced a privileged resolution in the House to disapprove the plan. That resolution got a hearing in the Government Operations Committee a week later, and even though most witnesses at the hearing supported the creation of the new department, and even though the committee recommended that Meader’s resolution be defeated by the House, when it came to the House floor on February 21, opponents of the new Department carried the day. Meader’s resolution rejecting President Kennedy’s plan passed the House convincingly, 264 yeas to 150 nays (with one voting “present”).

There the matter rested until Lyndon Johnson, fresh off being elected President in his own right and facing a much different Congress, sent Congress a special message on cities in March 1965 asking for the creation of a Cabinet-level Department of Housing and Urban Development.

This time, the rate at which Congress acted was striking. Senate hearings started before the end of March, House hearings started in early April, the bill was reported from committee in the House on May 11, got a rule from the Rules Committee on June 14, passed the House on June 16, was reported from committee in the Senate on August 2, passed the Senate amended August 11, was finalized by a House-Senate conference committee on August 26, and was signed into law by President Johnson on September 9. Six months and one week had passed between the day Johnson proposed the new Department and the day he signed the bill creating it.

The House, which had voted so lopsidedly against creating the new Department in February 1962, voted narrowly (217 to 184) to create the Department three years later (a 67-vote swing from the earlier vote). The Senate vote was 57 to 33.

In his remarks upon signing the bill into law (as Public Law 89-174), President Johnson did not mention transportation, and the issue didn’t come up often in the debate within Congress. Urban mass transportation programs from HHFA were transferred to the new HUD, along with everything else at HHFA.

When at HHFA, mass transit programs were under an Assistant Administrator (Transportation) who directly reported to Administrator Robert Weaver. But at HUD, mass transit was put under an Urban Transportation Administration whose Director then reported to the Assistant Secretary for Metropolitan Development, who in turn reported to Secretary Robert Weaver. In effect, mass transit had been bumped one level down in the organization chart by the creation of the new Department, and this was to become a critical factor in the later decision to take transit away from HUD a few years later.

Creation of DOT. [Please see Eno’s Documentary History of the Creation of the U.S. Department of Transportation for the full story excerpted below…]

While Congress was still debating the bill to create HUD in summer 1965, the Johnson White House was already looking forward to the next year’s agenda. White House aide Bill Moyers convened an interagency meeting on August 6 and formed an interagency task force to come up with ideas for the 1966 transportation legislative agenda, including “alternative reorganization plans.” The task force was chaired by Alan Boyd, the Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation.

By September 2 – a week before President Johnson signed the bill creating HUD into law – the initial working papers from the task force recommended, among other things, the creation of a Cabinet-level Department of Transportation, to include everything currently grouped at Commerce under the Under Secretary for Transportation (Bureau of Public Roads, Maritime Administration), the FAA (independent since 1958), the Coast Guard (from Treasury), St. Lawrence Seaway, the rail safety functions of the ICC, the aviation safety and subsidy functions of the Civil Aeronautics Board, and “the mass transportation activities of the Housing and Home Finance Agency.”

On September 22, LBJ himself approved the principle of creating a Department of Transportation (with no specifics) as part of the 1966 legislative program, writing “Hooray-!” (shown at left) on the decision memo.

A month later, on October 22, Boyd’s task force submitted a more detailed paper about what should go into a DOT, and it still made the case for moving mass transit to Transportation:

The development of Federally aided mass transit proceeds simultaneously with highway development aided by the Bureau of Public Roads. Coordination of policy, planning, and physical activity is essential. In terms of research and development and regional planning, this function is also related to the high-speed ground transportation effort of the Department of Commerce. Mass transit is a beginning Federal program, which could easily be transferred without a great amount of administrative difficulty or disruption of personnel. As a function it definitely belongs in the Federal transportation complex centered in a Department of Transportation.

-Boyd Task Force report, October 1965

About a month after that, however, on November 24, the Bureau of the Budget issued its own recommendations based on the Task Force reports, and questioned whether or not mass transit should be moved out of the new Housing Department:

A month later, in mid-December, Boyd was still holding fast on inclusion of mass transit at DOT. As late as January 4, 1966, Boyd sent Califano a memo stating:

The President’s decisions on transportation organization made no reference to urban transportation programs and how they are to be handled in a reorganization plan. I feel strongly that a new Department of Transportation must incorporate not only urban highway development programs now in Commerce but also the urban mass transportation development programs now located in HHFA. Incorporation of this latter program into a Department of Transportation becomes essential if we are to assure an integrated Federal approach to urban transport development requirements…

…We do not propose that comprehensive urban planning responsibilities of HUD be disturbed. HUD would continue to exercise responsibility for assuring that urban transportation plans are carrie don within the constrains of broader comprehensive planning procedures. Only the development aspects of the mass transit and the urban highway development programs would be lodged within the new DOT. In addition responsibility for research and development of all urban transport modes would be located in DOT.

-Alan Boyd, January 4, 1966

President Johnson announced his intention to create a Department of Transportation on January 12, 1966, in his State of the Union address, but the specifics of what constituent parts would be moved to the DOT were still in flux. White House staff were busy selling the general idea on Capitol Hill – domestic policy czar Joe Califano sent a memo to President Johnson on January 19 indicating that Sen. Abe Ribicoff (D-CT) “…may be interested in how mass transit and urban highways will be handled between the Department of Transportation and HUD. We are still trying to work this out.”

On January 26, a meeting was held at the White House where, according to an issue paper then put together by Charles Zwick, who was the Bureau of the Budget point man on these issues at the time, a decision was reached that:

Ultimately, DOT should be responsible for the following activities relating to Urban Transportation:

(1) Overall technical criteria for Government investments in urban transportation facilities.

(2) R&D on Urban Transportation facilities and equipment.

(3) Detailed planning and engineering of specific systems.

(4) Urban Transportation demonstration activities.

(5) Financing the development or improvement of urban transportation systems.

Ultimately, HUD should be responsible for the following activities relating to Urban Transportation:

(1) Overall general planning criteria for Government investment in urban facilities. In the case of transportation facilities, both public transit and urban highways should be under the purview of the department.

(2) Studies of the inter-relationships between various patterns of urban development and transportation requirements, including development of planning methodology, techniques of system analysis and model building which relate transportation to overall community development.

(3) Certification of the adequacy of urban development plans, including plans for all forms of urban transportation, as a basis for Federal financial assistance.

(4) Demonstrations designed to provide information useful in the preparation of plans, and in making planning decisions, including decisions on transportation plans.

-Zwick (Budget Bureau) issue memo based on January 25, 1966 meeting.

But that deal quickly unraveled. Zwick later remembered in an April 1969 oral history interview that: “In fact we had a meeting in Califano’s office one night I remember very clearly, with Califano, Schultze, Weaver, Boyd and myself, in which I outlined a solution which I insist to this day that they all agreed to. We then had a subsequent meeting over in the Bureau, an expanded meeting in which Schultze was there, Boyd was there, Lee White came over–he was still in the White House at that point and interested in transportation matters. When I outlined the solution I had evolved, all of them disowned it–Boyd, Schultze–so I gave up.”

Califano and Lee White wrote to the President on January 28 saying that the consensus was that only “Nuts and bolts research in Mass Transit” should be moved to DOT from HUD. Their memo amplified:

HUD Under Secretary Robert Wood later said in an oral history interview that “when that came out originally, mass transportation was scheduled to go from the new HUD to the new DOT. Charlie Haar and I noted this, suggested to Califano that we wait a year, and see if DOT was in fact established before we upset the troops. And Joe and the President agreed. So mass transportation was suspended with the provision that it be studied a year, which went on.”

When President Johnson finally submitted his formal message to Congress on March 2 requesting the creation of a Department of Transportation, it tried to emphasize the importance of the new HUD (which had only started operations in January 1966) and the new DOT:

The Departments of Transportation and Housing and Urban Development must cooperate in decisions affecting urban transportation.

The future of urban transportation–the safety, convenience, and indeed the livelihood of its users–depends upon wide-scale, rational planning. If the Federal Government is to contribute to that planning, it must speak with a coherent voice.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development bears the principal responsibility for a unified Federal approach to urban problems. Yet it cannot perform this task without the counsel, support, and cooperation of the Department of Transportation.

I shall ask the two Secretaries to recommend to me, within a year after the creation of the new department, the means and procedures by which this cooperation can best be achieved–not only in principle, but in practical effect.

-Lyndon Johnson, March 1966

The White House sent Government Operations Committee members a large, detailed briefing book on the proposal, which included a chapter (Tab 18) explaining the scope and importance of the proposed joint DOT-HUD study.

Hearings in the House and Senate began quickly. Senate hearings started first, on March 29, and the following day, HUD Assistant Secretary for Metropolitan Development Charles Haar testified. After discussing HUD’s primacy in urban planning issues generally, he also reminded the panel that Congress had recently, not once but twice, decided that the urban mass transportation program belonged primarily with the housing agency (though he did pay the necessary lip service to the need for a joint study of the issue with DOT):

Then Sen. Ribicoff, who the White House knew was specifically concerned about urban transportation issues and who was the only current Senator who had formerly been a Cabinet Secretary, started grilling Haar. Ribicoff started out by saying “…we set up the Department of Housing and Urban Development. I said then, and I still maintain that was a pretty weak bill and a pretty weak Department, and still is a weak Department” before asking “If we are going to have a Transportation Department, shouldn’t the Transportation Department have full jurisdiction over all matters of transportation?”

Haar talked about urban transportation being a “highly complex” problem and that “It is not only transportation, sir, but it is how it affects the pattern of land uses, the distribution of land values, the relation between residence and employment, the areas of city growth and the direction of metropolitan development. And so, clearly, certain aspects of this problem relate more to housing and land use than they do to the movement of people and goods…those aspects do not properly – cannot properly – be labeled transportation, although they flow from transportation.”

This did not sit well with Sen. Ribicoff, who responded, “Mr. Haar, you know when I say this, don’t misunderstand me: you have come new to the Federal Government as a consultant, and I have the highest respect for your ability. But it doesn’t take long to get sucked into the bureaucratic gobbledygook…one of the basic functions of this committee, Mr. Chairman, is to eliminate the duplication, the waste, the overlapping, the decentralization of responsibility. And I was hopeful that we were going to accomplish this in one field: transportation.”

Haar attempted to defend himself: “…I am not speaking solely in a bureaucratic guise this morning. I think that the concept of transportation – intellectually – can be sliced several different ways, and that you would not impair the coordination that this bill attempts to achieve by leaving in the Department of Housing and Urban Development certain functions which, while they are transportation in that they are movement of people and involve buses and roads and subways, are nevertheless even more intimately related in certain respects to city growth, city development, and the problems of housing.”

But Ribicoff closed by circling back to the original problem of commuter rail in the Northeast, the collapse of which in the late 1950s had been the original impetus for any federal role in urban mass transit whatsoever, and which also foreshadowed the development of metropolitan planning as a way to split the difference between city planning and statewide planning:

The commuters in the large metropolitan areas of the Nation, which cut across State lines, have to have all means of transportation coordinated so they can dovetail, so we can move people from their homes to work, and from work to their homes again. And whether it is the northeast corridor, with high-speed transportation, or whether it is taking the commuters from New Jersey and Connecticut, and pouring them onto the streets of jammed New York, whether they use subways or buses or the automobile, has to be done by one department with responsibility in a Secretary.

Now, I am for the Department of Transportation, but a real one.

Now, if we are going to have the same situation we have today, there is no sense in creating a new Department.

-Sen. Abraham Ribicoff (D-CT), March 1966

By June 24, the Senate committee staff sent panel members a memo summarizing all the hearings to date, and indicating that while the Administration still wanted transit at HUD for the time being, enough panel members and witnesses had expressed support for moving transit to DOT immediately that the staff had prepared an amendment doing so for possible consideration at the markup of the bill:

On June 29, Budget Director Schultze and Alan Boyd made a final appearance before the Senate panel before the the markup of the bill was to begin, and Ribicoff again pressed on the urban mass transit issue. Schultze, on behalf of the White House, responded:

…let’s assume, for example, the decision were made to move urban mass transit to [DOT]. I just don’t think it is that simple a decision. It has to be linked up to what you do about the relationship of transportation to urban planning and who says what and how you lay this out so that on the one hand you do get all considerations brought into it, but on the other hand, you don’t mess it up with so much red tape that it won’t work.

Quite frankly, what we have recommended here is that urban mass transit not be moved and that the two Secretaries, once the Department of Transportation is established, will directly come up to the President with a special report on how this can be done and make appropriate recommendations to Congress on that…

…It seems to me it has to be done in terms of a pretty comprehensive agreement between the two Departments involving some legislative changes, substantive changes, some agreement on planning and relationship of planning between the two Departments. It ought to be done by the two Secretaries with a comprehensive plan. This is quite frankly the reason we did leave it out there, but the President has provided that there will be a solution.

-Bureau of the Budget Director Charles Schultze, June 29 1966

The Senate committee then met for a markup session on July 14, and then a second one on July 19, but neither one came to a final conclusion. (This staff memo summarizes amendments adopted at the first two markup sessions, but no amendments to that point concerned mass transit.) At that point, the Senate committee just suspended consideration of the bill.

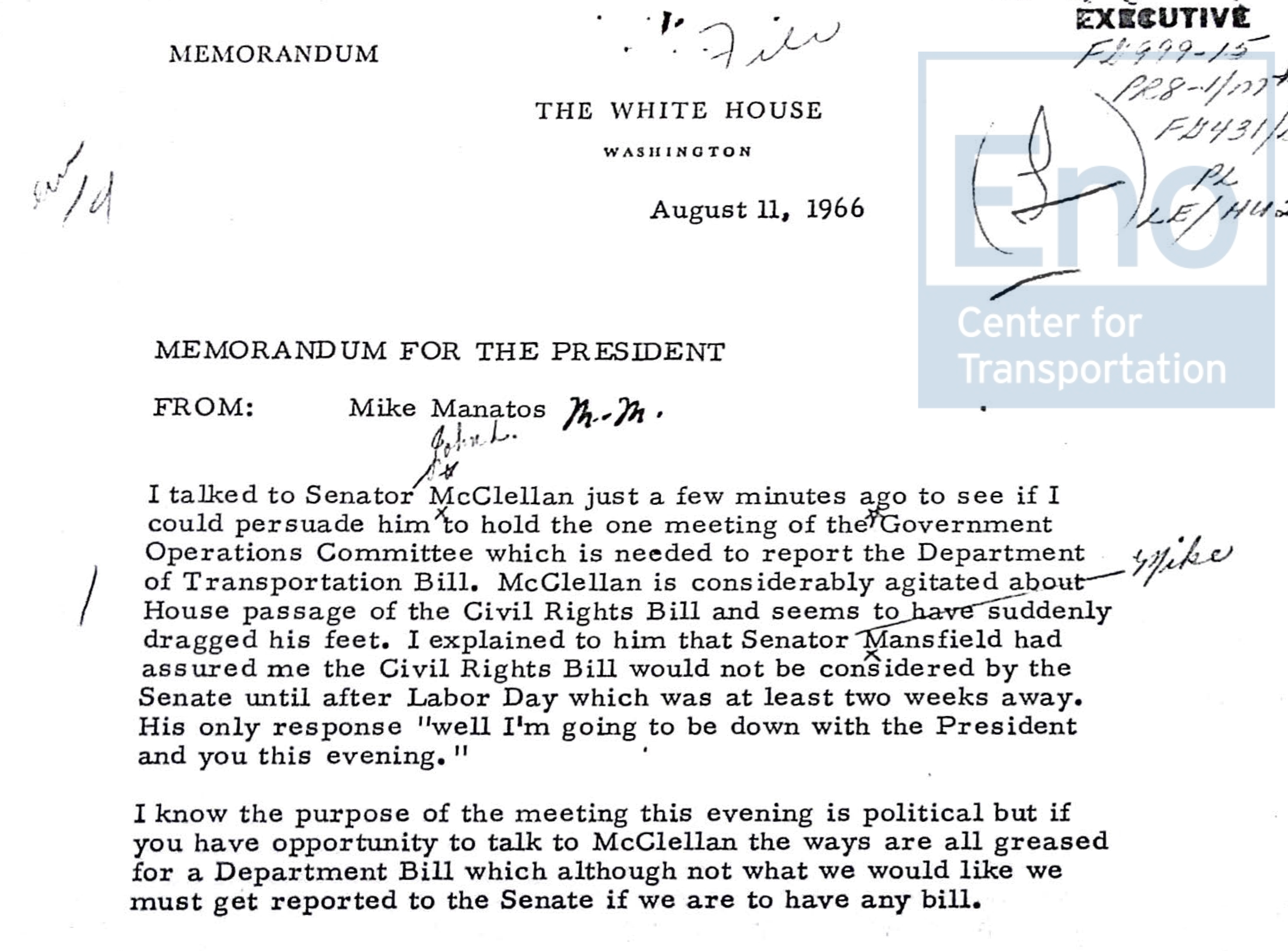

An internal White House memo to President Johnson on August 11 reveals that some of the delay rested with Government Operations chairman John McClellan (D-AR):

Things had been moving more quickly in the House. At their early hearings, Director Schultze got into a discussion with several members on the transit location issue (see page 72-75 of the hearings). In particular, in response to a question from Rep. Florence Dwyer (R-NJ) as to what would happen if DOT and HUD could not agree to proceed:

Mrs. DWYER. Suppose there is a conflict in this study. Shouldn’t we hold up this bill until those conflicts are resolved, and from the standpoint of economy, should’t mass transportation really be—

Mr. SCHULTZE. By holding up the bill, you are not any closer to a solution of these problems, and you postpone the solution to other problems. It seems to me you clearly don’t create any greater inefficiencies or conflicts because we are going to study it for a year.

And, on the other hand, there are other areas in which the urban problem is not at issue, where we believe the new Department will create efficiencies. So we don’t see any gain from holding up the Department – that would maintain the existing inefficiencies, and would not contribute in and of itself to the solution of the remaining inefficiencies.

The Bureau of the Budget later produced a helpful document summarizing the major questions raised at the House hearing and giving “talking points”-style answers. The answer to the question of “why wait for a joint DOT-HUD study” was “For the study to take place with any hope for successful outcome there must be a Secretary who really speaks for transportation to deal with a Secretary who speaks for urban development. Creation of the Department of Transportation is, therefore, a necessary preliminary to any resolution of transportation-urban relationships.”

The House committee marked up and approved the DOT bill on June 29. The committee report was filed on July 15 and noted “The President has said he intends, upon the creation of the Department of Transportation, to ask the heads of the two Departments concerned to study and report within 1 year on a logical and efficient organization of urban mass transportation functions. It may well be that these functions will be lodged in the new Department. The committee considers that the President’s proposed course is reasonable and that the final organizational decision on urban mass transportation should be deferred.”

The House bill was brought to the floor in late August, where Rep. Dwyer did offer an amendment to make the joint DOT-HUD study of urban mass transit issues a requirement of law – not just an administrative directive by the President – and to require the study to be complete within one year of the effective date of the Act. With support from the bill manager, her amendment passed by voice (see p. 21236 here), and the bill passed the House by the landslide margin of 336 yeas to 42 nays on August 30.

But in the Senate, it still seemed that progress on the DOT bill was going to depend on the outcome of the civil rights bill. That took more time – the House had passed a bill on August 9 and then Majority Leader Mansfield used rule XIV to bypass committee referral in the Senate and move the bill straight to the floor calendar. The motion to proceed to the civil rights bill came ten votes shy of the then-necessary two-thirds of those voting on September 14 (the vote was 54-42) and then came up ten votes short again on a second cloture vote on September 19 (52-41). After that, the Majority Leader publicly admitted defeat and told the Senate he would not try to bring the bill up again during that Congress.

Not coincidentally, the Government Operations Committee then met and approved the DOT Act (S. 3010, 90th Congress) on September 22. The Senate bill as reported from committee, in section 4(g), contained a provision requiring ongoing DOT-HUD studies of what to do about urban mass transit, with annual reporting, but (unlike the House bill’s Dwyer amendment) no strict requirement that the issue of which department got custody of mass transit be settled within one year.

Within one week of the committee reporting the bill, the Senate had debated and passed the DOT bill by a margin of 64 yeas, 2 nays and then moved to a House-Senate conference committee, using the House bill (H.R. 15963, 90th Congress) as a vehicle. The agenda for the conference committee suggested just using Dwyer’s language (see item 7 here).

The conference committee did just that, with the conference report filed on October 12 adopting Dwyer’s language:

The Secretary and the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development shall study and report within one year after the effective date of this Act to the President and the Congress on the logical and efficient organization and location of urban mass transportation functions in the Executive Branch.

Congress quickly passed the conference report by wide margins, and President Johnson signed the bill into law on October 15 as Public Law 89-670. But the issue of whether urban mass transit was more about transportation or more about urban development would have to wait for the joint DOT-HUD study, which in turn had to wait for DOT to be formally established, which took until April 1, 1967.

Part three, dealing with the decision to move mass transit from HUD to DOT in 1968, is here.