January 11, 2019

This week, Virginia governor Ralph Northam announced that he and a bipartisan group of state legislators are proposing legislation to levy tolls across the 325-mile length of Interstate 81 throughout the state in order to pay for $2.2 billion in capacity and safety upgrades to the corridor. But even if the General Assembly agrees to the plan, it will still require multiple permissions (and a loan) from the U.S. Department of Transportation.

The governor and legislators are endorsing the spending plan of, and one of the tolling options recommended by, the I-81 Corridor Improvement Plan which was endorsed by the Commonwealth Transportation Board last month.

How to spend $2.2 billion. The report notes that I-81 carries 42 percent of Interstate truck VMT through the Commonwealth – 11.7 million trucks per year carrying $312 billion in goods annually. I-81 also sees an average of 2,200 crashes per year, and at least 45 of those annual crashes require more than four hours to clear, resulting in backups of 20 miles or more on a routine basis. Delays are amplified by the changes in altitude along the route (it peaks at around 2,500 feet and drops as low as 700 feet in elevation, which disproportionately slows truck traffic. The report notes that “From a traffic flow and congestion standpoint, when truck percentage and terrain are considered, a single tractor-trailer truck accounts for the equivalent of as many as four passenger cars on certain segments of the corridor.”

(The author of this article has been driving a 375-mile stretch of I-81 from Northern Virginia to its southern terminus at I-40 at holidays for almost 30 years now and can attest firsthand to the increase in truck volume over that time making it a miserable slog, particularly northbound on Sundays.)

It appears that the $2 billion capital cost total was decided first, and then the projects were selected. The report states that:

The $2 billion in funding was divided 50/50 between a [VDOT] district allocation and a corridor-wide allocation. The first step was to sub-allocate the district $1 billion share by the centerline miles in each district on I-81. Identified improvements in each district were sorted based on their respective benefit/cost score and defined as a “project.” The second step was to allocate the corridor-wide priority funding, which used the remaining $1 billion. Unfunded projects that remained after the first step in all three districts were sorted by benefit/cost score until the $1 billion was allocated.

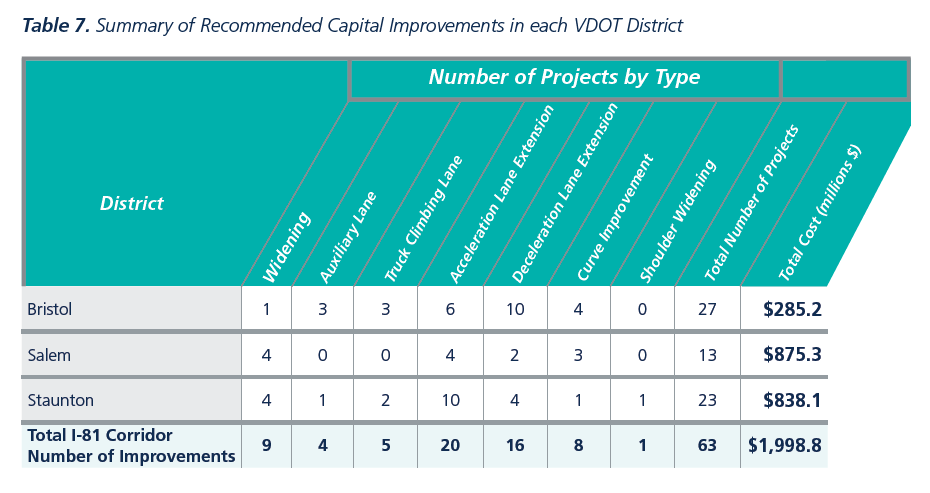

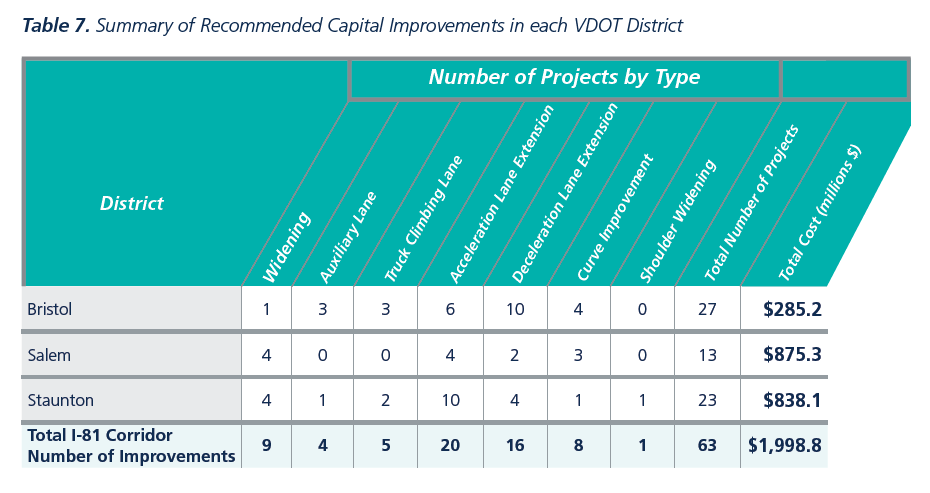

The centerline miles were 87.5 in the Bristol district, 87.0 in the Salem district, and 150.5 in the Staunton district, so the first $1 billion would have been split $269 million, $268 million, and $463 million respectively. Then the corridor-wide $1 billion went predominantly to projects in the Salem district. The resulting project selection looks like this:

The report also proposes spending $200 million on immediate operational improvements, truck parking solutions, speed enforcement, and multimodal improvements. The report estimates that the $2.2 billion in improvements will result in 450 fewer crashes per year (a 20 percent decrease) and an aggregate savings of 6 million hours of delay per year.

How to raise $2.2 billion. The report analyzed a variety of tax and spend options, but the tax options were limited by Virginia politics. Previous experiments in regional road taxation in the Greater DC area and the Hampton Roads area meant that any tax increases would have to be implemented by five different regional districts along the 325-mile route. A revenue option that included those five jurisdictions levying an 0.7 percent sales and use tax increase and a 2.1 percent motor fuels sales tax increase was considered and rejected (presumably in part because the freight benefits of I-81 are statewide, not confined to those counties adjoining the Interstate).

The political leaders then looked at the four tolling options presented by the report. All of the tolling options had a truck focus because, in the words of the report, “Cost responsibility studies and other pavement impact research concludes that one 5-axle truck impacts the infrastructure of an interstate the same as at least 5,600 passenger vehicles. The pavement cost of each 5-axle truck was estimated in 2008 to be 2.1 cents per mile per axle or $11,760 per truck.” The four options were:

|

|

Toll Rate – Cents/Mile |

Auto |

|

|

Trucks |

Autos |

Pass |

| Option 1 |

Trucks Only |

15¢ |

n/a |

No |

| Option 2 |

Trucks and Auto Non-Commuters |

15¢ |

10¢ |

No |

| Option 3 |

Variable Day/Night w/ Auto Non-Commuters |

15¢ day, 7.5¢ night |

10¢ day, 5¢ night |

No |

| Option 4 |

Variable Day/Night w/ Annual Auto Pass |

15¢ day, 7.5¢ night |

7.5¢ day, 5¢ night |

$30/yr |

“Day”” is defined as 6 a.m. to 9 p.m. and the variable day/night pricing options are intended to encourage truck traffic to drive overnight at less congested hours. Under all the options, a truck driving the length of I-81 in Virginia in the daytime would pay $48.75.

The governor and legislators chose Option 4 because it had the lowest toll levels that were able to support the $2.2 billion program and because it gave local motorists the option to buy an RFID sticker or EZ-Pass option for $30 per passenger car, SUV or pickup truck per year for unlimited use. (There may have been another reason – see below.)

The tolls are to be collected electronically, via EZ-Pass and camera tolling, with monitoring gantries erected every 40 miles or so.

Federal permission. Tolling I-81 is not as simple as the General Assembly simply passing a law. Federal law for over 102 years has prohibited states from tolling roads that were originally built with federal dollars (including Interstates), with a few narrow exceptions. The Virginia plan identifies three separate exception programs in the law that could, with Federal Highway Administration permission, allow Virginia to toll I-81.

- Value Pricing Pilot Program. This program, originally established by the 1991 ISTEA law, no longer has any grant money to give out but can still, according to its website, “enter into cooperative agreements for projects that require tolling authority under this program for their implementation.” The fact that the governor and legislators selected a toll option with variable day/night pricing makes this a valid option for federal tolling permission.

- Interstate System Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Pilot Program. This program, established by the 1998 TEA21 law, gave up to three states the authority to toll existing Interstate corridors, but it has never been successfully used. The FAST Act of 2015 ordered FHWA to rescind prior approvals that were never used and request new applications, which happened in an October 2018 Federal Register notice.

- Section 129 Program. This longstanding program in 23 U.S.C. §129 was originally an exception for toll bridges, tunnels, and ferries but, Virginia says, can also be used for corridor-wide tolling “if toll gantries are near or on reconstructed or rehabilitated bridges.”

Virginia will need USDOT consent through FHWA to enter into at least one of these three programs in order to levy tolls on I-81. And that’s not all…

Financing plan. The financing plan for the $2 billion capital program is predicated on the assumption that USDOT will grant Virginia a $650 million TIFIA loan early in FY 2021 with a 39-year repayment schedule (the first four years of which would be a grace period). Another $900 million would be raised through the issuance of 35-year state toll revenue bonds. That totals $1.55 billion in financing, and then the toll receipts would be sufficient to support the other $450 million of capital costs over the six years it would take to complete the construction process, and then to start paying debt service while maintaining operational costs. (See Appendix J of the report for the details.)

Assuming that the tolls stay in place through the year 2067 (and yes, financial assumptions that far out are barely worth the ink they are printed on), Virginia assumes they will raise a total of $10.9 billion in nominal dollars. After the $200 million in immediate operational improvements over the first 6 years and the $452 million in capital costs over the first 6 years, $3.3 billion would be used for debt service on the TIFIA loan and the toll bonds over their lifetime, and an additional $1.4 billion would be used for operations and maintenance. This would still leave $5.5 billion in future toll collections available and presumably usable for other capital costs in the upcoming decades without increasing toll rates, and the report estimates that the net present value of that $5.5 billion at a discount rater of 4.5 percent is $1.6 billion in today’s dollars.

Other actions necessary. Since I-81 was specifically built to parallel the old U.S. 11, a key question has always been “if you toll I-81, won’t the trucks just divert to Route 11 to avoid tolls?” The 2018 act of the General Assembly that authorized the corridor financing study also directed the study to “Identify actions and policies that will be implemented to minimize the diversion of truck traffic from the Interstate 81 corridor, including the prohibition of through trucks on parallel routes…” But the report appears to be light in this area, so presumably it would have to be filled in by the state implementing legislation.