January 18, 2017

As Washington, DC largely shuts down to make way for the inaugural ceremonies of Donald J. Trump (and the related protests), persons in the transportation and infrastructure sector anxiously await information on President-elect Trump’s much-talked-about infrastructure plan, about which there are almost no details. We may get some clues if President Trump submits a broad budget outline to Congress in late February.

But based on what Trump personally has said (and tweeted) so far, the only real details are that the infrastructure plan will “Buy American and Hire American.” This is a line that has been in several speeches and tweets since the election so one can assume that it has been vetted with the Trump Tower senior advisors and represents policy.

But what are the implications of “Buy American and Hire American” for federal transportation and infrastructure policy?

Buy America (lose the “n”). To begin with, one must distinguish between the types of laws already on the books. There was a “Buy American Act” enacted all the way back in 1933 (and codified at 41 U.S.C. §§8301-8305) – but the Buy American (with an “n” at the end) only applies to goods purchased by the federal government directly via contracts or purchase orders “for the construction, alteration, or repair of any public building or public work.” (See a Congressional Research Service summary here.) This naturally excludes contracts made with grants that the federal government makes to states, transit agencies, airport authorities, federally-owned corporations, and other non-federal entities.

Most federal construction grant programs in the transportation field are now covered by a series of “Buy America” (no “n”) laws that vary from mode to mode and which were enacted by Congress over a period of years starting in the mid-1970s in reaction to the collapse of the domestic steel industry.

Since Buy America was a response by Congress to domestic steel industry priorities, this observation from an article in The Economist’s January 7, 2017 issue is relevant:

[Trump] has assembled advisers with experience in the steel industry, which has a rich history of trade battles. Robert Lighthizer, his proposed trade negotiator, has spent much of his career as a lawyer protecting American steelmakers from foreign competition. Wilbur Ross, would-be commerce secretary, bought loss-making American steel mills just before George W. Bush increased tariffs on imported steel. Daniel DiMicco, an adviser, used to run Nucor, America’s biggest steel firm. Peter Navarro, an economist, author of books such as Death by China and now an adviser on trade, sees the decline of America’s steel industry as emblematic of how unfair competition from China has hurt America.

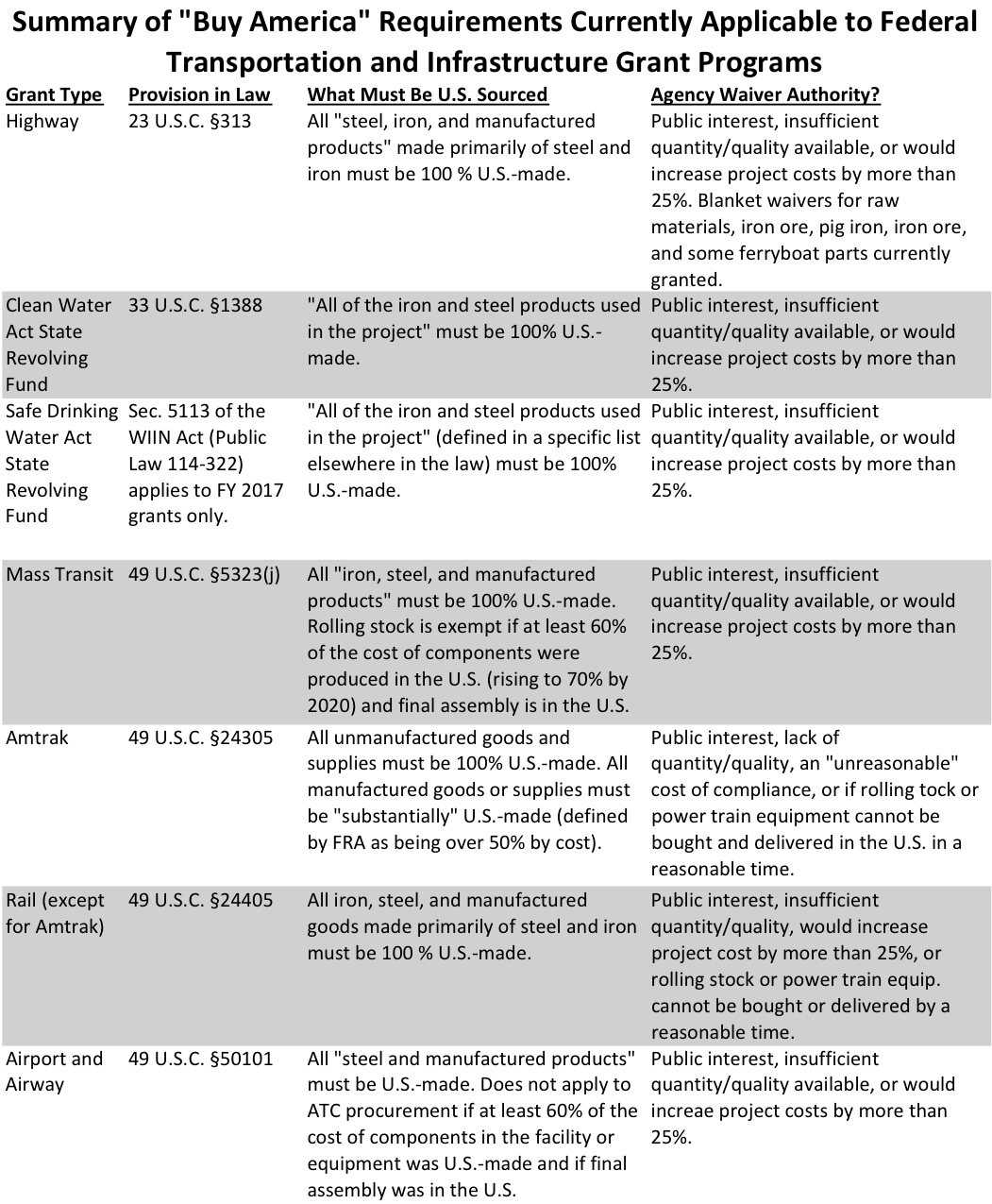

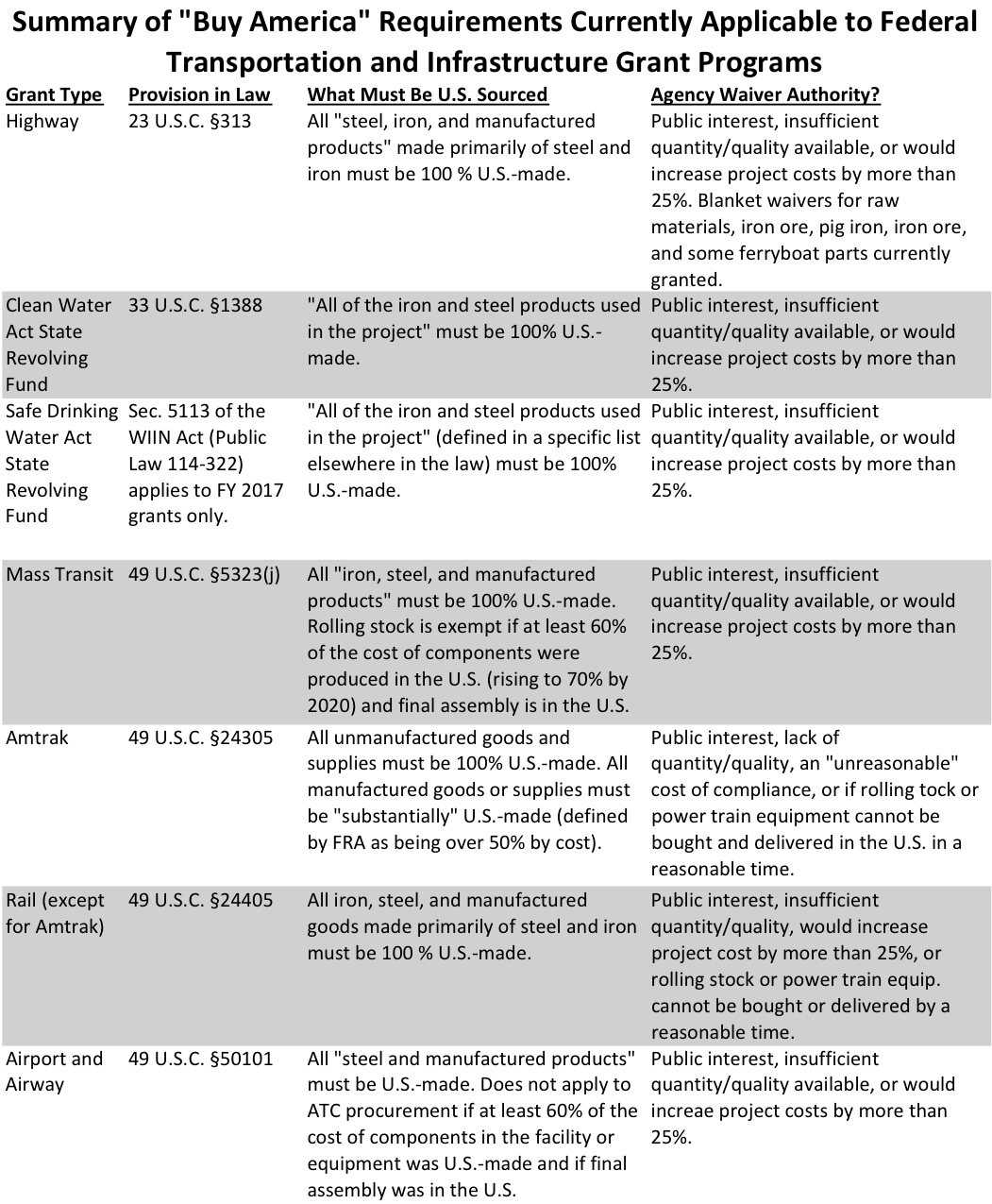

These separate Buy America provisions now apply to federal-aid highway grants (23 U.S.C. §313), federal mass transit grants (53 U.S.C. §5323(j)), and grants to Amtrak (49 U.S.C. §24305(f)) (all since 1978); Federal Aviation Administration airport grants and other procurements (49 U.S.C. §50101) since 1990; and the rail improvement grant programs established the PRIIA law in 2008 and the FAST Act of 2015 (49 U.S.C. §24405(a)). Congress has also added temporary Buy America provisions to appropriations bills that only apply to the funding appropriated for that year. For example, section 1605 of the 2009 ARRA stimulus law applied a domestic content requirement to contracts funded by that law.

Starting in fiscal 2014, Congress has added Buy America provisions to the annual appropriations laws requiring that year’s grants made under the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act to capitalize state revolving funds (SRFs). See section 436 of Division G of Public Law 113-76 for FY 2014, section 424 of Division G of Public Law 113-235 for FY 2015, and section 424 of Division G of Public Law 114-113 for FY 2016. This provision for Clean Water Act SRFs was actually made permanent law by section 5004 of the 2014 WRRDA law, but the provision applicable to Safe Drinking Water Act grants is still temporary and was extended through April 28, 2017 in the continuing resolution but was then superseded by the water resources bill.

(The Senate-passed WRDA bill last summer contained a provision (sec. 7117 of S. 2848) that would have made the Buy America provision applicable to Safe Drinking Water Act SRFs permanent law, but the House watered this provision down to FY 2017 only and listed more specific items to which it applies – see sec. 2113 of the enrolled WIIN Act.)

All of these various Buy America statutes have a few things in common:

- They require that all iron and steel purchased by contracts funded by the program be produced in the United States.

- There is a de minimis purchase level below which the Buy America rules do not apply ($100,000 for purchases under FTA and FRA contracts, $1 million for Amtrak purchases, the larger of $2,500 or 0.1 percent of the contract price for purchases under FHWA contracts).

- For grants that fund the purchase of manufactured goods (locomotives, rail cars, buses, etc.), the domestic content requirement is loosened – at FTA, for example, at least 60 percent of the cost of the locomotive, train car or bus must be from domestic components, and the final assembly must be in the United States. (The FAST Act amended this so that the 60 percent level will rise to 70 percent by 2020.) For Amtrak, the requirement is more vague, saying that manufactured goods have to be “substantially from articles, material, and supplies mined, produced, or manufactured in the United States.” (FRA defines “substantially” as over 50 percent of the cost.)

- The federal government agency that administers the grant program has the statutory authority to waive the Buy America requirements on a case-by-case basis.

The grounds under which the government can grant Buy America waivers are:

- If the agency determines the waiver is “in the public interest;”

- If the agency determines that the materials and products are not produced in the U.S. in sufficient quality or quantity to fulfill the need; and

- If the agency determines that compliance with Buy America would increase total project cost by more than 25 percent.

Waivers can be specific, or they can be “blanket” – for example, after a nationwide shortage, FHWA issued a blanket Buy America waiver in 1995 for pig iron and types of iron ore that is still on the books. Lists of recent waiver requests and determinations are here from FHWA, FTA, and FRA. Waiver requests also have to have a public comment period – a large waiver request from the California High Speed Rail Authority last September was withdrawn two months later after loud public criticism.

Given the President-elect’s well-known 30-year opposition to trade deals he views as unfair, one other distinction between Buy American and Buy America is relevant. Certain trade deals have superseded application of the Buy American act relating to direct federal procurement. However, section 1001 of NAFTA specifically does not apply NAFTA’s ban on “domestic content” requirements to “cooperative agreements, grants, loans, equity infusions, guarantees, fiscal incentives, and government provision of goods and services to persons or state, provincial and local government.” (See this 1994 letter from FHWA confirming that NAFTA does not affect Buy America rules for highway construction projects.) And Annex 2 of the Government Procurement Agreement of the World Trade Organization specifically says in Note 5 (at the end) that the WTO rules “shall not apply to restrictions attached to Federal funds for mass transit and highway projects” (though they presumably do supersede FAA and FRA rules, however).

Economics is always about tradeoffs, and there is a cost to protecting U.S. industrial jobs. A November 2015 report from the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service notes that buses used in public transportation cost significantly more in the U.S. than they do in Japan and South Korea, resulting in less value per dollar spent by the Federal Transit Administration than spent by overseas counterparts. The proposed XpressWest high-speed rail line from Las Vegas to Southern California was denied a federal RRIF financing loan because, Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood wrote in 2013, “The FRA expects recipients of RRIF loans to purchase steel, iron, and other manufactured goods produced in the United States in their projects…”

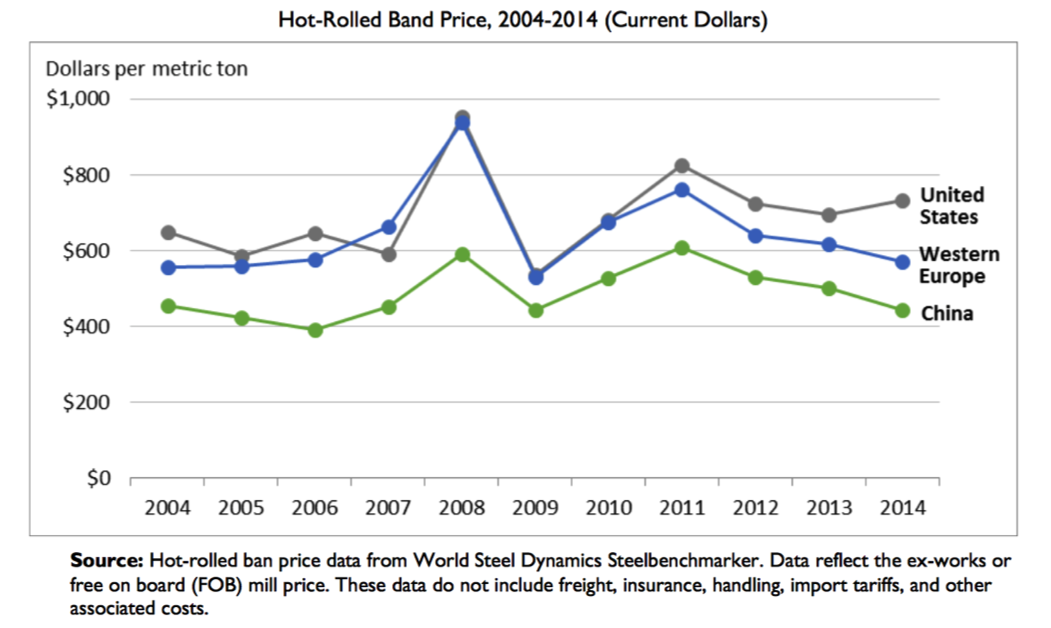

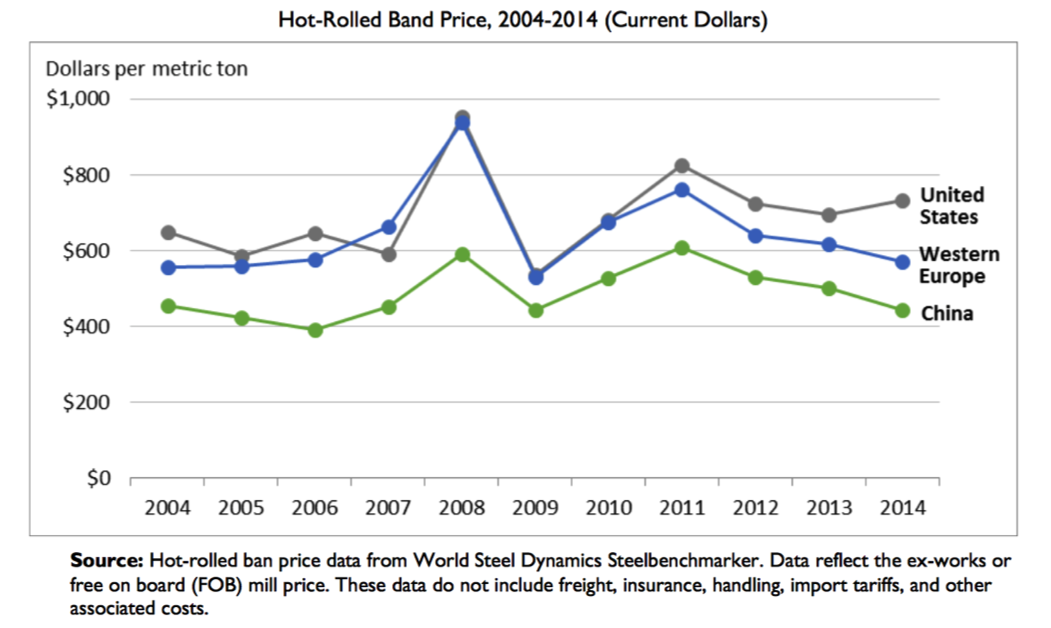

And the CRS report also showed that U.S.-made steel is almost always significantly higher in price out of the mill than is European- or Chinese-made steel (though the cost of oceanic and subsequent overland transport to U.S. job sites may mitigate that somewhat):

If the Trump Administration decides that the greater costs are worth the job sustainment or creation that would come from stronger Buy America requirements, what could they do?

The most obvious answer is simply to stop giving out Buy America waivers, or at least be much more stingy with them. This is something that Transportation Secretary-designate Elaine Chao can direct USDOT employees to do on her first day, with no recourse by Congress, state DOTs or transit/rail agencies. (In the memo to President Carter from his domestic policy staff upon his signing of the first Buy America provision relating to transit rolling stock, the White House staff noted that the original provision had been “watered down by giving the Secretary of Transportation authority to waive this requirement…DOT intends to make liberal use of the waiver authority.”)

Chao certainly seems to have received the message. During her confirmation hearing before the Senate Commerce Committee last week, there was the following exchange with Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI):

BALDWIN: [The House GOP] position against Buy America is at stark odds with the President-elect, who has repeated his pledge that there will be two rules for rebuilding America’s infrastructure: quote, “Buy American and hire American.” So if confirmed you will undoubtedly play a leading role in implementing the president-elect’s infrastructure plan.

But it’s noteworthy to me that you have previously been critical of Buy America rules. In 2009 you wrote an op-ed describing Buy America as, quote, “dig a moat around America policy.” This is in a Heritage Foundation op-ed. And to further quote you, you said Buy America squanders America’s credibility on international trade.

So I want to tease out how this conflict might be resolved. And my question is, if confirmed as secretary of transportation will you stand with the president-elect and support Buy America?

CHAO: The president has made very clear his position on this and it is his policy. And of course all Cabinet members will follow his policy…

BALDWIN: …given your past views on Buy America restrictions, I, I guess I’d like to hear more about how you would intend to use that authority to waive Buy America restrictions, how you would evaluate what is in the public interest, and under what …my specific question is under what conditions would you see granting these waivers, or will you grant them sparingly or frequently?

CHAO: I think it is premature at this point for me to comment on any of this until I get fully briefed. I have mentioned that Buy America is the president’s priority. When you drill down to some of the details that you talked about, thank you so much for bringing it to my attention. I am not fully cognizant about that.

So, if confirmed, I look forward to getting briefed on all those issues.

By working with Congress legislatively, President Trump could strengthen existing Buy America provisions in other ways – though these would be among the provisions he would have to pursue with Democratic votes over significant Republican opposition. The Obama Administration, in the 2015 iteration of its GROW AMERICA bill, proposed (in sec. 3006) to increase the mass transit rolling stock domestic content requirement from 60 percent to 100 percent over five years (the GOP would only go along with an increase from 60 to 70 percent over that time). And the Administration proposed new Buy America rules for rail grants (in sec. 9205 of the bill) that would have applied to non-federal funds in FRA grant projects and would have required final assembly of rolling stock in the United States.

Also, because the various Buy America requirements for the different transportation grant programs were written at different times and often by different committees in Congress, there are some inconsistencies that Congress could close in legislation. Rep. Dan Lipinski (D-IL) had a bill in the last Congress (H.R. 2451, 114th Congress) that would have closed the CMAQ bus loophole (at present, localities can use federal highway grants under the CMAQ program to buy buses that don’t meet the same domestic content requirement as buses that the same locality purchases using federal transit grants).

Lipinski’s bill also suggested some other changes to the various Buy America statutes (requiring better documentation and measurements of percentage value for transit rolling stock purchases, better sourcing for suppliers for FRA grants, extending Buy America requirements to airport projects funded by local passenger facility charges (PFCs)). (Online update, 2/8/17: Lipinski reintroduced an updated version of his bill in the new 115th Congress on February 7 as H.R. 905.)

“Hire American” – trust, or verify? As with the “Buy American” promise made by President-elect Trump, there are already some laws and rules relevant to this, and again there are separate legal regimes that apply to direct federal procurement as opposed to federal grant programs.

The landmark 1986 immigration law, right up front in section 101, made it “unlawful for a person or other entity to hire, or recruit or refer for a fee, for employment in the United States…an alien knowing the alien is an unauthorized alien” or to hire any individual without checking citizenship or work permit paperwork. This law (punishable with civil fines for initial offenses but with up to six months in jail for a pattern of violations) is still on the books at 8 U.S.C. §1324a. The law applies to all employers – the private sector, federal and local governments, everyone.

However, Social Security cards and birth certificates don’t have photographs, biometrics or other forms of identification and are just as easy to forge now as they were 30 years ago. A Social Security card is still all you need to prove employment authorization, and a birth certificate gets you a drivers’ license to prove identity. (And there are quite good fake drivers license mills out there, or so the teenagers say.)

In order to get President Reagan to sign the 1986 bill, its sponsors had to add an “affirmative defense” provision protecting employers by allowing them to say, in essence, “I didn’t know the documents this alien presented were fake” and generally be believed. The actual provision of law states “A person or entity that establishes that it has complied in good faith with the requirements [to examine documents] with respect to the hiring, recruiting, or referral for employment of an alien in the United States has established an affirmative defense that the person or entity has not violated [the prohibition] with respect to such hiring, recruiting, or referral.”

(Many employers over the years have used the affirmative defense to get away with massive fraud with a nod, nod, wink, wink attitude towards documentation that any unbiased person would assume was fake – this author’s high school was a few blocks away from a poultry processing plant that was notorious in this regard.)

The 1986 law also contained a blanket statement that nothing in the law could be construed to authorize the issuance or establishment of a national ID card. This (and the cost and privacy issues) has prevented the government from making too many modifications to Social Security cards in particular to make them harder to fake. But the numbers on the Social Security cards cannot be faked – a number was either issued by Social Security and corresponds with a particular person’s name, or it doesn’t. The problem has always been developing a way to verify that Social Security numbers match the name on the piece of paper in a speedy and reliable way.

Enter E-Verify. A 1996 immigration law update (in title IV of Division C of the law) established a pilot program for electronic verification of Social Security numbers/names and data from the immigration service that would be immediate (over a toll-free telephone line at first, and now over the Internet). This “basic pilot program” from the 1996 law has been extended over and over by Congress in anticipation of being made permanent in a comprehensive immigration reform law that has never come. It is now known as E-Verify and is used by over 500,000 employers, including over 70,000 “specialty trade contractors” (as defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which includes a lot of construction subcontractors for concrete, etc.) and by 24,000 building contractors.

However, by law, participation in E-Verify is generally voluntary at the decision of the employer. President George W. Bush did issue an executive order in June 2008 (EO 13465) that became effective in September 2009, which requires the following:

Executive departments and agencies that enter into contracts shall require, as a condition of each contract, that the contractor agree to use an electronic employment eligibility verification system designated by the Secretary of Homeland Security to verify the employment eligibility of: (i) all persons hired during the contract term by the contractor to perform employment duties within the United States; and (ii) all persons assigned by the contractor to perform work within the United States on the Federal contract.

But no such federal requirement is yet applicable to contracts made by states, transit agencies, airports, etc. using the money provided by federal grants. The decision on whether or not to require contractors to be E-Verify compliant is up to state or local law, and many of the biggest states and transit agencies apparently do not require their contractors on federal grants have to participate in the E-Verify program.

According to data from the construction industry, California, by far the largest state, does not require that its contracts go to contractors participating in E-Verify (though the Golden State does have a law barring contractors that have been convicted in court in the last five years of violating immigration laws). Other big states like New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin apparently don’t have state laws or executive orders mandating that contractors be E-Verify compliant, either.

President Trump could well decide that the price for state and local participation in his infrastructure program could be full contractor compliance with E-Verify. From a policy and administrative perspective, it is unclear how many contractors and subcontractors are out there who are not currently E-Verify compliant and who are still receiving funds that stem from federal transportation and infrastructure grants. It could be a minor problem to solve, or it could significantly increase labor costs in some areas – we just don’t have the information.

But that issue is separate from whether or not requiring E-Verify compliance in the Trump infrastructure plan could pose political problems for states and cities. Past Trump comments about immigration have prompted an uproar in states and cities with large Latino populations, some of which have seen their political leaders declare that they will refuse to comply with any Trump Administration requests for compliance with new immigration directives or enforcement policies. The act of simply accepting federal dollars that come with an E-Verify requirement could turn into a political controversy in some of these areas.

There is also the constitutional question of to what degree Congress can retrofit existing grant programs to force states to change policy or else have their grants confiscated. The existing U.S. Supreme Court doctrine on this is actually from a Department of Transportation case (South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 207 (1987)) where South Dakota fought the process by which Congress was encouraging states to raise their drinking ages to 21 by threatening to withhold 5 percent of certain highway formula grants from states which did not comply.

Under the precedent, Congress cannot use “compulsion” under the Spending Clause of the Constitution but it can use the “mild encouragement” of a 5 percent highway funding cut. However, in South Dakota, the Court was dodging the question of whether or not the federal government had any power at all to set a drinking age after the 21st Amendment had been ratified – because they ruled that a 5 percent cut in certain highway formula funds was not coercion, they didn’t have to decide if Congress had power to be coercive in that particular goal.

Court-watchers may remember that it was South Dakota that was the precedent cited by the Supreme Court in the subsequent 2012 decision (NFIB v. Sibelius) to overturn the Affordable Care Act’s requirement that states expand their Medicaid coverage or else lose all Medicare funds. (See Chief Justice Roberts’ discussion on pages 50-58 of the slip opinion.) The Court ruled starting on p. 55 that:

What Congress is not free to do is to penalize States that choose not to participate in that new program by taking away their existing Medicaid funding. Section 1396c gives the Secretary of Health and Human Services the authority to do just that. It allows her to withhold all “further [Medicaid] payments . . . to the State” if she determines that the State is out of compliance with any Medicaid requirement, including those contained in the expansion. 42 U. S. C. §1396c. In light of the Court’s holding, the Secretary cannot apply §1396c to withdraw existing Medicaid funds for failure to comply with the requirements set out in the expansion…As a practical matter, that means States may now choose to reject the expansion; that is the whole point.

Note that this legal doctrine only applies to modifications to existing federal grant programs – a new federal infrastructure grant program set up to include an E-Verify requirement from the beginning might be treated differently by the courts than would be a modification to existing highway or transit grant program. (If any sharp constitutional lawyers out there feel more certain of an answer, please let us know.)

It may interest readers to know that the Buy America and Hire American ideas first originated in the same legislation 40 years ago next month, along with another important contract-related provision. (Those not interested in history can skip ahead to the table at the end of the article with a quick comparison of all the existing Buy America provisions, but what would be the fun in that?)

The 1977 jobs bill – jobs for who? In October 1973, when the Yom Kippur War between Israel and its Arab neighbors broke out, the U.S. unemployment rate was 4.8 percent. When the U.S. predictably sided with Israel, the Arab oil exporting nations (OAPEC) stopped selling oil to the U.S. and all oil exporting nations generally acted together to raise prices. This doubled the price of oil in the United States – it went from $3.39 per barrel in 1972 (annual average) to $6.95 per barrel in January 1974. This naturally produced massive inflation and job losses. By May of 1975, the unemployment rate had doubled to 9.0 percent, and even though it receded somewhat, it stayed stubbornly high in the 7 to 8 percent range through 1976.

Congress wanted job creation (and, of course, they wanted something specific they could vote for to say they shared in the credit for creating said jobs). In May 1975, the House passed a bill (H.R. 5247, 94th Congress) authorizing a $5 billion program of grants to cities and counties for job-creating public works programs. After negotiations with the Senate, this amount was cut in half, but when the bill was finally sent to President Ford, he vetoed it in February 1976, saying that the bill would create too few jobs, too late, and at an “intolerably high” cost of over $25,000 per job. The House overrode the veto, 319-98 (Democrats had a veto-proof majority at that time in the House), but the Senate narrowly sustained the veto, 63-35.

Congress quickly regrouped, and the Senate passed a revised new bill (S. 3201, 94th Congress) in May 1976. After negotiations with the House, a final version with a $2 billion public works authorization passed the Senate with a veto-proof 70 votes in June 1976 and then passed the House 328-83. Two days after the Bicentennial celebrations, President Ford vetoed the revised bill, citing the same reasons as in the first veto message. But this time, Congress had the votes to override the veto (73-24 in the Senate and 310-96 in the House). It became Public Law 94-369 on July 22, 1976. Less than six weeks later, Ford signed the appropriations bill providing the $2 billion for public works jobs that had just been authorized (Public Law 94-447) because, his staff wrote in a signing memo, “There is virtual certainty that the 94th Congress would override your veto…”

Even though Democratic House and Senate gains in the 1976 elections were negligible, the capture of the White House by Jimmy Carter meant that Democrats in Congress immediately began trying to revisit in 1977 what they had wanted in 1976. On January 4, 1977, the Opening Day of the 95th Congress, Rep. Bob Roe (D-NJ) of the House Public Works and Transportation Committee introduced H.R. 11, which amended the 1976 law to increase the funding authorization for the local public works grants from $2 billion to $6 billion. The bill was reported by Public Works on February 16, which added the first Buy America requirement attached to a federal construction grant:

Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no grant shall be made under this Act for any local public works project unless only such unmanufactured article, materials, and supplies as have been mined or produced in the United States, and only such manufactured articles, materials, and supplies as have been manufactured in the United States substantially all from articles, materials and supplies mined, produced, or manufactured, as the case may be, in the United States, will be used in such project.

The committee report said that “Reliance on compliance can be based on assurances given by the applicant.” When the bill came to the House floor on February 24, Rep. Sam Gibbons (D-FL) offered an amendment to strike the Buy America provision from the bill, saying that “Unless my amendment is adopted, about the only thing one can build is an adobe hut from rainwater and mud.”

Future chairman Jim Oberstar (D-MN) responded:

…this debate has lost sight of some essential language in the bill, and that essential word is “substantially.” The bill does not say 100 percent. The committee was very careful in writing that language and in considering the Buy American feature. It says “substantially” and it does not say 100 percent.

We had testimony before our committee that the structural steel industry, imports have risen to some 30 percent of domestic consumption, imports from countries where there is unemployment but where there is substantial subsidy from governments to those competing industries, where there is unfair foreign competition with domestic production, and we wanted to make sure in this public works bill that we would create jobs in the United States and that we are not disadvantaging any part of American industry.

A Republican on Public Works, Rep. Bill Harsha (R-OH), offered a separate alternative amendment to Gibbons’ language, giving the Secretary of Commerce (who was going to administer the public works program through the Economic Development Administration) authority to waive the Buy America rule on the grounds of public interest or lack of sufficient quantity or quality of domestic materials. The Harsha waiver language was adopted by voice vote, and the Gibbons amendment to strike then failed on a voice vote. The amended Buy America language stayed in the version of the bill that was passed by the House.

Later that day, Rep. Mario Biaggi (D-NY), a former police officer from the Bronx, offered an amendment with the following additional language:

No grant shall be made under this Act for any local public works project unless the State or local government applying for such grant submits with its application a certification acceptable to the Secretary that no contract will be awarded with such project to any bidder who will employ on such project any alien in the United States in violation of the Immigration and Nationality Act or any other law, convention, or treaty of the United States relating to the immigration, exclusion, deportation, or expulsion of aliens.

Biaggi’s amendment reflected what he said was “a universal sense of agreement on the need to prohibit illegal alien employment,” noting that earlier that month Attorney General Griffin Bell had called for a law prohibiting the hiring of illegal workers. After a long speech emphasizing his point that “Illegal aliens must not be permitted to compete with American citizens for these jobs,” the majority and minority bill managers (Roe and Rep. John Paul Hammerschmidt (R-AR)) accepted the amendment without debate and it passed by voice vote.

One other revolutionary amendment to the bill passed on the House floor that day. Rep. Parren Mitchell (D-MD), chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, offered an amendment that added:

Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no grant shall be made for any public works project unless at least 10 per centum of the dollar volume of each contract shall be set aside for minority business enterprise and, or, unless at least 10 per centum of the articles, materials and supplies which will be used in such project are procured from minority business enterprises.

Mitchell noted that a move towards minority business set-asides was already underway in some states but not yet at the federal level. Roe offered an amendment to water down Mitchell’s language somewhat, adding an “except to the extent that the Secretary determines otherwise” to the very beginning and requiring that “the applicant gives satisfactory assurance to the Secretary” that the contract would meet the 10 percent MBE threshold. These changes were adopted by voice vote. Then, after Biaggi spoke about how his Hire American language shared the same goal as the DBE set-aside, the House passed the Mitchell amendment, as amended, by voice vote.

The House had passed the first Buy America requirement for federal grants, the first Hire American provision (almost a decade before the federal government would outlaw the hiring of undocumented workers), and the first minority business set-aside applicable to federal grants, all in the same bill on the same day – February 24, 1977.

The Senate-passed version of the bill included the House-passed Buy America requirement and a slightly modified 10 percent MBE set-aside but dropped the House’s Hire American requirement. In conference, the House won on all these issues. The conference report passed the Senate 71 to 14, passed the House 335-77, and was signed into law by President Carter on May 13, 1977 as Public Law 95-28. Moments later, Carter signed the appropriations bill providing the remaining $4 billion for the public works jobs program into law as Public Law 95-29.

The Buy America and MBE set-aside provisions of the Public Works Employment Act of 1977 began to be added by Congress to other federal grant programs the following year, but the law’s Hire American provision promoted by Rep. Biaggi did not (though it is still on the books as a valid law at 42 U.S.C. §6705(e), it only applies to that specific EDA public works grant program for which no money has been appropriated in 40 years).

(Ed. Note: The 1980 U.S. Supreme Court case that held MBE set-asides to be constitutional, Fullilove v. Klutznick (448 U.S. 448 (1980)), was in response to the Mitchell-Roe amendment to the 1977 law.)