Eno conducted an analysis of the international market for air travel in November 2018 for the Japan International Transport Institute. This multi-part ETW series details some of the most interesting facts and findings of that work. Although the research does not predict the future or propose any recommendations, the results are instructive for thinking about how international air service has evolved over the past few decades.

The data analyses use three data sources: (1) publicly available data from the U.S. Department of Transportation (T-100 dataset), (2) Sabre Corporation’s Market Intelligence Data and Analytics, and (3) existing reports and other publicly available information. The data from Sabre is not publicly available, but the Eno Center for Transportation was able to gain access through a subscription paid for by the Japan International Transport Institute, USA. Sabre uses public and private data to create a suite of data resources which analyzes traffic trends and fills in gaps missing in the T-100 dataset. The data available during the creation of this report includes a “final” dataset from 2010-2017, where Sabre’s algorithms verify the accuracy and update data points as necessary. The data set also includes “preliminary” MIDT (Marketing Information Data) data from 2002-2009. While this data is not as precise as the final dataset, it can provide enough information for broad trends.

International travel hinges on complex agreements between countries that allow companies to transport people across borders. Open Skies agreements are the most common form of bilateral and multilateral international aviation agreements, setting up the possibility for airline alliances. While the industry and the public are generally in support of Open Skies, it is not without controversy.

Open Skies agreements are bilateral or multilateral air service agreements between two or more countries. They provide rights for private airlines to offer international passenger and cargo service between the countries without government control of routes, pricing, capacity, and schedules. Prior to Open Skies, bilateral agreements between countries determined fares and service frequencies.[1]

The first Open Skies agreement was reached between the United States and the Netherlands in 1992. Since then, the agreements have proliferated; the U.S now has agreements with 120 other countries. In addition to bilateral Open Skies air transport agreements, the United States has negotiated two multilateral Open Skies accords:

- The 2001 Multilateral Agreement on the Liberalization of International Air Transportation (MALIAT) with New Zealand, Singapore, Brunei, and Chile, later joined by Samoa, Tonga, and Mongolia; and

- The 2007 Air Transport Agreement with the European Community and its Member States.

Table 1 includes a list of all the Open Skies agreements that the U.S. has with other countries.

Table 1: Current U.S. Open Skies Agreements, October 2018

| Partner |

Application |

Date |

Partner |

Application |

Date |

|

| Netherlandsi |

In Force |

10/14/92 |

Uruguay |

In Force |

10/20/04 |

|

|

| Belgiumi |

Provisional |

3/1/95 |

India |

In Force |

1/15/05 |

|

|

| Finlandi |

In Force |

3/24/95 |

Paraguay |

In Force |

5/2/05 |

|

|

| Denmarki |

In Force |

4/26/95 |

Maldives |

In Force |

5/5/05 |

|

|

| Norwayi |

In Force |

4/26/95 |

Ethiopia |

In Force |

5/17/05 |

|

|

| Swedeni |

In Force |

4/26/95 |

Thailand |

In Force |

9/19/05 |

|

|

| Luxembourgi |

In Force |

6/6/95 |

Mali |

In Force |

10/17/05 |

|

|

| Austriai |

In Force |

6/14/95 |

Bosnia And Herzegovina |

In Force |

11/22/05 |

|

|

| Icelandi |

In Force |

6/14/95 |

Cameroon |

Provisional |

2/16/06 |

|

|

| Switzerland |

In Force |

6/15/95 |

Cook Islandsii |

In Force |

2/28/06 |

|

|

| Czech Republici |

In Force |

12/8/95 |

Chad |

Provisional |

5/31/06 |

|

|

| Germanyi |

Provisional |

2/29/96 |

Kuwait |

In Force |

8/30/06 |

|

|

| Jordan |

In Force |

11/10/96 |

Liberia |

In Force |

2/15/07 |

|

|

| Singaporeii |

In Force |

1/22/97 |

Canada |

In Force |

3/12/07 |

|

|

| Taiwan |

In Force |

2/28/97 |

Bulgariai |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| Costa Rica |

In Force |

5/8/97 |

Cyprusi |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| El Salvador |

In Force |

5/8/97 |

Estoniai |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| Guatemala |

In Force |

5/8/97 |

Greecei |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| Honduras |

Provisional |

5/8/97 |

Hungaryi |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| Nicaragua |

In Force |

5/8/97 |

Irelandi |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| Panama |

In Force |

5/8/97 |

Latviai |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| New Zealandii |

In Force |

5/29/97 |

Lithuaniai |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| Bruneiii |

In Force |

6/20/97 |

Sloveniai |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| Malaysia |

In Force |

6/21/97 |

Spaini |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| Aruba |

In Force |

9/18/97 |

United Kingdomi |

Provisional |

4/30/07 |

|

|

| Chileii |

In Force |

10/28/97 |

Georgia |

In Force |

6/21/07 |

|

|

| Uzbekistan |

In Force |

2/27/98 |

Australia |

In Force |

2/14/08 |

|

|

| Korea |

In Force |

4/23/98 |

Croatia |

In Force |

3/13/08 |

|

|

| Peru |

In Force |

6/10/98 |

Kenya |

In Force |

5/30/08 |

|

|

| Romaniai |

In Force |

7/15/98 |

Laos |

In Force |

10/3/08 |

|

|

| Italyi |

Provisional |

11/11/98 |

Armenia |

In Force |

10/6/08 |

|

|

| U.A.E. |

In Force |

4/13/99 |

Zambia |

In Force |

3/16/10 |

|

|

| Pakistan |

In Force |

4/29/99 |

Israel |

In Force |

4/23/10 |

|

|

| Bahrain |

In Force |

5/24/99 |

Trinidad & Tobago |

In Force |

5/1/10 |

|

|

| Tanzania |

Provisional |

11/3/99 |

Barbados |

In Force |

7/1/10 |

|

|

| Portugali |

In Force |

12/22/99 |

Japan |

In Force |

10/25/10 |

|

|

| Slovak Republici |

In Force |

1/7/00 |

Colombia |

In Force |

11/11/10 |

|

|

| Namibia |

C&Riii |

2/4/00 |

Brazil |

In Force |

3/19/11 |

|

|

| Burkina Faso |

In Force |

2/9/00 |

Saudi Arabia |

In Force |

4/18/11 |

|

|

| Turkey |

In Force |

3/22/00 |

St. Kitts |

In Force |

11/28/11 |

|

|

| Gambia |

In Force |

5/2/00 |

Montenegro |

In Force |

12/5/11 |

|

|

| Nigeria |

Provisional |

8/26/00 |

Suriname |

In Force |

6/21/12 |

|

|

| Morocco |

In Force |

10/5/00 |

Sierra Leone |

In Force |

6/26/12 |

|

|

| Ghana |

In Force |

10/11/00 |

Macedonia |

In Force |

8/23/12 |

|

|

| Rwanda |

In Force |

10/11/00 |

Seychelles |

In Force |

12/12/12 |

|

|

| Maltai |

In Force |

10/12/00 |

Yemen |

C&Riii |

12/12/12 |

|

|

| Benin |

In Force |

11/28/00 |

Guyana |

In Force |

3/25/13 |

|

|

| Senegal |

In Force |

12/15/00 |

Bangladesh |

C&Riii |

8/15/13 |

|

|

| Polandi |

In Force |

5/31/01 |

Botswana |

In Force |

12/12/13 |

|

|

| Oman |

In Force |

9/16/01 |

Equatorial Guinea |

In Force |

8/7/14 |

|

|

| Qatar |

Provisional |

10/3/01 |

Burundi |

C&Riii |

11/18/14 |

|

|

| Francei |

In Force |

10/19/01 |

Togo |

In Force |

4/7/15 |

|

|

| Sri Lanka |

In Force |

11/1/01 |

Serbia |

In Force |

5/29/15 |

|

|

| Uganda |

In Force |

6/4/02 |

Ukraine |

In Force |

7/14/15 |

|

|

| Cabo Verde |

In Force |

6/21/02 |

Côte d’Ivoire |

In Force |

10/20/15 |

|

|

| Samoaii |

In Force |

7/4/02 |

Azerbaijan |

In Force |

4/6/16 |

|

|

| Jamaica |

In Force |

10/30/02 |

Curacaoiv |

In Force |

9/26/16 |

|

|

| Tongaii |

In Force |

9/19/03 |

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

In Force |

4/7/17 |

|

|

| Albania |

In Force |

9/24/03 |

Republic of the Congo |

C&Riii |

5/30/17 |

|

|

| Madagascar |

In Force |

3/10/04 |

BES |

In Force |

1/17/18 |

|

|

| Gabon |

In Force |

5/26/04 |

Guinea |

C&Riii |

3/19/18 |

|

|

| Indonesia |

C&Riii |

7/26/04 |

Sint Maarten |

In Force |

4/1/18 |

|

|

|

Grenada |

In Force |

4/10/18 |

|

Source: U.S. Department of State, Open Skies Partners, October 9, 2018

Table Notes:

i. The U.S.-EU Air Transport Agreement, signed April 30, 2007, was provisionally applied March 30, 2008 for all 27 European Union Member States at that time. Norway and Iceland became party to the U.S.-EU agreement pursuant to an agreement signed and provisionally applied June 11, 2011.

ii. Multilateral Agreement on the Liberalization of International Air Transportation

iii. Applied on the basis of comity and reciprocity

iv. The agreement is between the United States and the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in respect of Curacao.

The U.S. Department of State supports Open Skies agreements, calling them “pro-consumer, pro-competition, and pro-growth … Open Skies agreements improve flexibility for airline operations, expand cooperative marketing opportunities between airlines, enable global express delivery cargo networks, liberalize charter regulations, and commit both governments to high standards of safety and security.”[2] An analysis by InterVISTAS Consulting found that liberalization of air service between two nations “will typically increase traffic by roughly 16 percent.”[3] A 2015 study by the Brookings Institution yielded similar findings.[4]

The U.S. does not have Open Skies agreements with several countries in Asia, including China, Vietnam, and the Philippines. In the case of China, the U.S. signed a 2007 non-Open Skies air transport protocol that includes restrictions on frequencies and code sharing.[5] Its language solidified what researchers called “the most liberal and flexible bilateral traffic rights regime” in China.[6] Australia soon followed suit, signing a full open skies agreement with China at the end of 2016.

The barrier to a full bilateral Open Skies agreement between the U.S. and China boils down to slots for planes at airports. Currently, there are limits on the number of flights that U.S. airlines can operate to foreign airports and vice versa. For instance with China, past discussions to increase the allowed number of flights fell through because U.S. carriers feared Chinese airports would not have slots for the additional U.S. carrier flights or would grant priority slots to Chinese carriers.[7] The Australia-China agreement was anticipated to benefit both countries, but with a heavy unbalance towards more business for the Chinese carriers.[8] An Open Skies agreement with the U.S. would likely benefit China more than the U.S., thus increasing the barrier to incentivize the U.S. to negotiate.[9]

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) believes increased airport capacity would mitigate problems around competition for slots.[10] Both the U.S. and China are funding and encouraging respective domestic airport construction in the next decade.[11] Increased capacity could improve the environment for establishing an Open Skies agreement between the two countries. But Open Skies agreements also apply to freight aviation, not just passenger flights. This makes negotiations more complicated because of the current U.S. Administration’s protectionist stance on trade between the two countries.

There are also third-party countries that have a stake in Sino-U.S. aviation agreements. In recent years, Hong Kong and Tokyo have absorbed some of the passenger volume between the U.S. and China, providing a connection where those passengers may otherwise have taken non-stop flights (See analysis in Section 3). Cheaper fares, higher frequencies, and more flight options may be contributing to these new markets.[12] Hong Kong does not have a domestic aviation market and thus has not entered open skies agreements with many countries.[13] In 2017, the Airport Authority of Hong Kong signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Paris airports operator Group ADP to co-operate in cargo flights.[14]

The Philippines and Vietnam have only recently entered Open Skies agreements with other countries. The Philippines signed its first agreement in 2016, when it joined the ASEAN Open Skies Policy for Southeast Asian countries.[15] The country is improving the quality of their air service to match increased international competition.[16] Vietnam entered ASEAN Open Skies in 2015, and both its passenger and cargo aviation markets are expected to continue to expand as a result of increased demand and investment in additional airport capacity.[17] Research found no public knowledge of ongoing Open Skies negotiations between the U.S and Philippines and Vietnam.[18]

From Open Skies to Airline Alliances

Airline alliances are cooperative agreements between U.S. and foreign carriers that establish limited marketing arrangements, such as a reciprocal frequent flier program or an international code-share agreement that allows an airline to sell seats on a partner’s planes as if they were its own.[19] Alliances make it easier for passengers to fly internationally, providing a seamless service between cities that otherwise would not have non-stop service on the same airline. To form these alliances, airlines need anti-trust immunity (ATI) from the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), and an Open Skies or similar type of agreement (such as the 2007 Sino-U.S. agreement) with the foreign carrier’s home country is an essential prerequisite to receive the ATI grant.[20]

The first airline alliance was between Northwest Airlines and KLM, a Dutch carrier, quickly following the first Open Skies agreement between the U.S. and the Netherlands. The benefits of ATI became so attractive to carriers following the KLM/Northwest decision that “foreign government interest in Open Skies relationships with the United States began to increase dramatically.”[21]

The U.S. government has been very supportive of ATI-based alliances since the first one in the 1990s. The U.S. State Department wrote: “By allowing U.S. air carriers unlimited market access to our partners’ markets and the right to fly to all intermediate and beyond points, Open Skies agreements provide maximum operational flexibility for airline alliances.”[22]

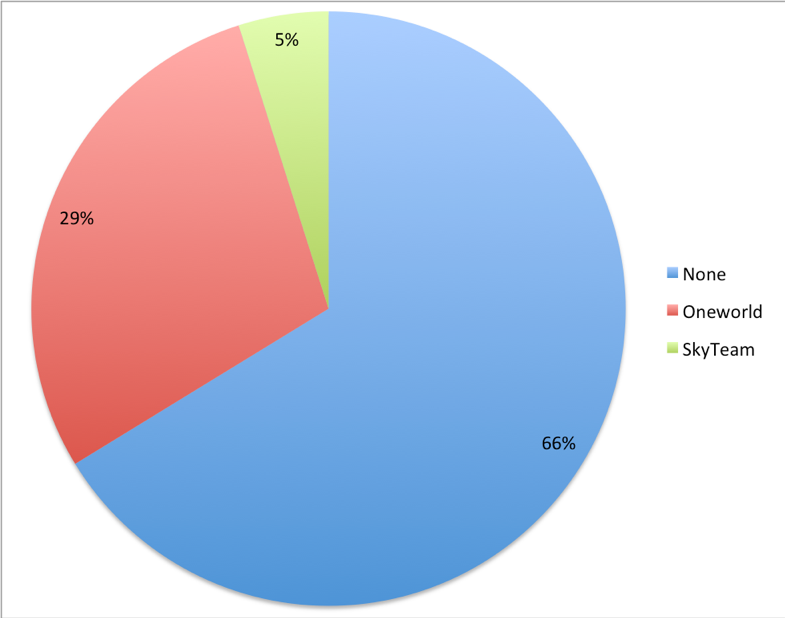

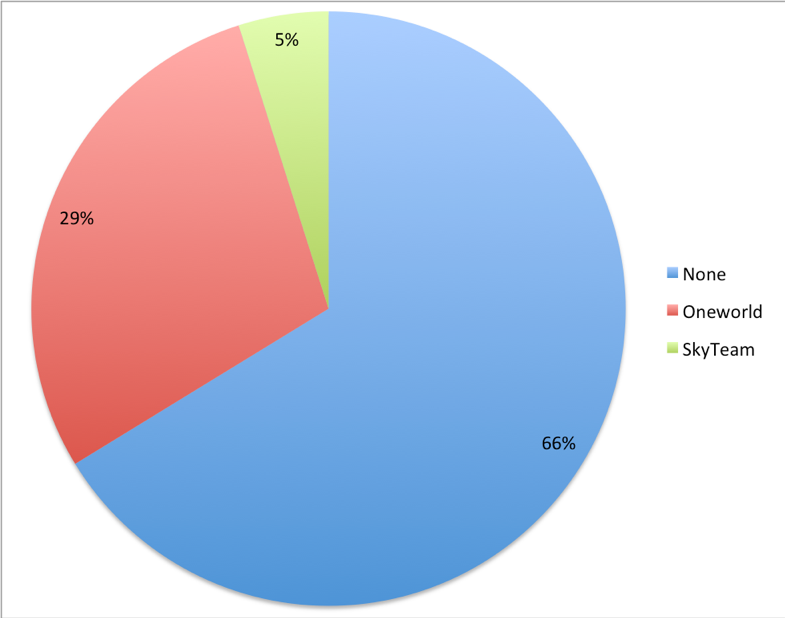

Currently there are three primary airlines alliances (Table 2), and 79 percent of all international travelers to and from the United States fly on one of the three alliances (Figure 1). Most of passengers flying on non-alliance carriers tend to be traveling shorter distances, with those carriers largely serving markets in Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean.[23]

Table 2: The Major Three Airline Alliances

| Star Alliance (1997) |

Oneworld (1999) |

SkyTeam (2000) |

| United Airlines* |

American Airlines* |

Delta Air Lines* |

| All Nippon Airways |

Japan Airlines |

China Airlines |

| Air China |

Cathay Pacific* |

China Eastern Airlines |

| Air India |

Malaysia Airlines |

China Southern Airlines |

| Asiana Airlines |

Qatar Airways |

Garuda Indonesia |

| EVA Air |

Royal Jordanian |

Korean Air* |

| Shenzhen Airlines |

SriLankan Airlines |

Middle East Airlines |

| Singapore Airlines |

British Airways* |

Saudia |

| Thai Airways International* |

Finnair |

Vietnam Airlines |

| Adria Airways |

Iberia Airlines |

XiamenAir |

| Aegean Airlines |

S7 Airlines |

Aeroflot |

| Austrian Airlines |

LATAM |

Air Europa |

| Brussels Airlines |

Qantas |

Air France* |

| Croatia Airlines |

|

Alitalia |

| LOT Polish Airlines |

|

Czech Airlines |

| Lufthansa* |

|

KLM |

| Scandinavian Airlines* |

|

TAROM |

| Swiss International Air Lines |

|

Aerolíneas Argentinas |

| TAP Portugal |

|

Aeroméxico* |

| Turkish Airlines |

|

Kenya Airways |

| Avianca |

|

|

| Copa Airlines |

|

|

| EgyptAir |

|

|

| Ethiopian Airlines |

|

|

| South African Airways |

|

|

| Air Canada* |

|

|

| Air New Zealand |

|

|

*Founding Member

Sources: Star Alliance, Oneworld, SkyTeam

Figure 1: US Departing Passengers by Alliance, 2017

Source: Air Carrier Statistics (Form 41 T-100), “International Segment, 2017,” Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 2018

Since 2015, three additional alliances have formed: the Vanilla Alliance, U-Fly Alliance, and Value Alliance. These do not contain any U.S.-based airlines, and they are very small compared to the major three. Dozens of major airlines have not joined an alliance, including many domestic low cost carries (Southwest, Frontier, JetBlue), gulf carriers (Etihad, Emirates), and low cost international carriers (RyanAir, Norwegian Air)

Open Skies Controversies

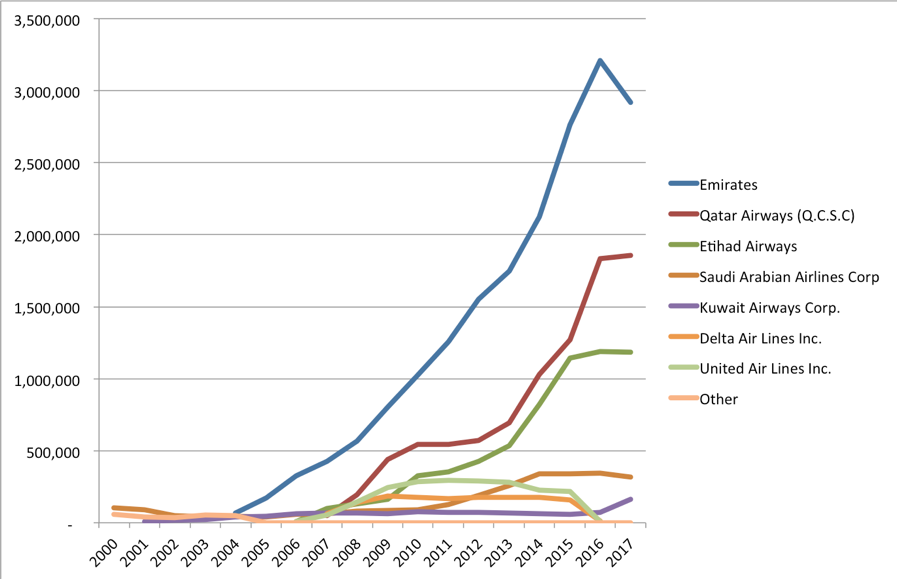

Some Open Skies agreements have been controversial, particularly in the case of the U.S. agreements with Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Traffic on Qatar Airways, Emirates, and Etihad Airways has increased dramatically since the signing of Open Skies agreements with their home countries. U.S. airlines claim that the Gulf carriers receive excessive state subsidies, and therefore they are not fair actors in the international aviation market.[24] The three largest U.S. carriers launched a formal campaign in 2015 demanding that the Middle East increase transparency and work within the rules of the Open Skies agreement.

The provisions intended to allow a “fair and equal opportunity” for airlines in both countries to compete are specifically at issue. This entails government involvement to be limited to “protection of airlines from prices that are artificially low due to direct or indirect governmental subsidy or support.” The major U.S. carriers claim that Qatar, Emirates, and Etihad are in violation of Open Skies because they allegedly have received $52 billion in direct government subsidies since 2004.[25]

Others counter by citing government subsidies and support for U.S. airlines in indirect ways.[26] For example, bonds issued by state or municipal-owned airport authorities are tax-free. Thus, when an airline invests in an airport (e.g., building a new terminal), they typically let the airport authority issue the bonds so they can have better financing conditions than if the airlines went to market themselves. Chapter 11 bankruptcy laws could also be considered to be a subsidy since they allow airlines to restructure their debts or offload responsibilities for their pension liabilities.[27]

In January 2018, the U.S. reached an agreement with Qatar to resolve the dispute, requiring Qatar Airlines to release audited financial statements, disclose transactions with state-owned entities, and commit to not increasing current flight schedules.[28] Similar to the agreement the United Arab Emirates, Qatar committed to freeze plans for additional “fifth freedom” passenger flights. The U.S. freight carrier FedEx, which operates a Dubai hub and several “fifth freedom” flights, is unaffected in the agreement.[29] In press releases, Delta and American called the agreements and “important step” and a “step forward,” indicating that more action might be needed after the release of audited financial statements.

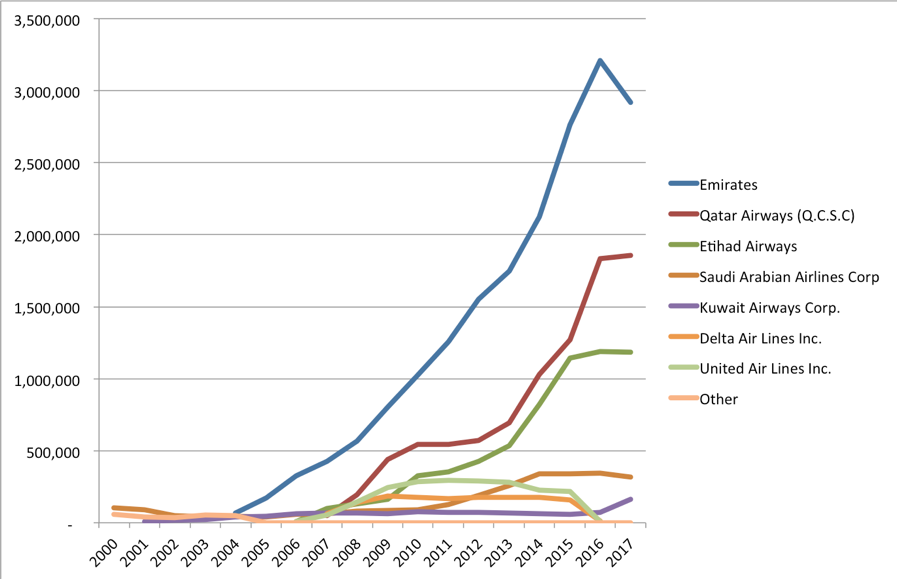

Air Traffic on the Gulf Carriers

The attention paid to Open Skies and the Gulf Carriers is directly tied to their dramatic growth in passenger air traffic. Qatar Airways set up a hub in Qatar, and Emirates and Etihad Airways have hubs in the U.A.E. These airlines route passengers through their hubs to serve markets in the Middle East and Asia, with approximately 82 percent of all their traffic connecting to another destination. These airlines currently carry about 35 percent of all U.S. traffic to and from India. While a few non-stop U.S.-India routes exist, most of the other traffic connects through Europe or Asia.

Figure 2 shows the rapid growth of passenger traffic to Qatar and UAE, although 2017 data shows the carriers have cut back flights and halted their dramatic growth. Qatar, Emirates, and Etihad have all claimed they do not plan to add more flights in the coming years.

Figure 2: Departing Passengers to Gulf Countries

Source: Bureau of Transportation Statistics, T-100 International Market (All Carriers)

Qatar Airways participates in the Oneworld alliance, but Etihad and Emirates are not part of one of the three major airline alliances. This makes the U.S to Gulf market one of the few that has little interaction with airline alliances.

Figure 3: Passengers to Gulf, by Alliance, 2017

Source: Bureau of Transportation Statistics, T-100 International Market (All Carriers)

[Continued in the third installment, which discusses the role of polar routing, aircraft design, and the changing dynamics of flights to Asian countries. Part 1 of the series can be found here.]

[1] Cliff Winston, Jia Yan, “Open skies: Estimating travelers’ benefits from free trade in airline services,” Brookings Institution, May 2015. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Open-Skies-Published.pdf

[2] U.S Department of State, “Open Skies Partnerships: Expanding the Benefits of Freer Commercial Aviation,” 2018; U.S. Department of State, “Civil Air Transport Agreements,” 2018 https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/272590.pdf

[3] InterVISTAS Consulting, Inc, “The Economic Impacts of Air Service Liberalization,” June 11, 2015. https://www.intervistas.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/The_Economic_Impacts_of_Air_Liberalization_2015.pdf

[4] Cliff Winston, Jia Yan, “Open skies: Estimating travelers’ benefits from free trade in airline services,” Brookings Institution, May 2015. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Open-Skies-Published.pdf

[5] U.S. Department of State, “Civil Air Transport Agreements,” 2018; U.S. Department of State, “U.S.-China Air Transport Agreement of July 9, 2007.” https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/114853.pdf

[6] Lei, Z., M. Yu, R. Chen, and J.F. O’Connell, “Liberalization of China-US Air Transport Market: Assessing the Impacts of the 2004 and 2007 Protocols,” Journal of transport geography, 50, 2016, pp. 24-32

[7] CAPA, “US-China Open Skies: A Window in 2019 – Alignment of Airline Partnerships & Airport Infrastructure.” CAPA – Centre for Aviation, 2017 https://centreforaviation.com/analysis/reports/us-china-open-skies-window-in-2019-with-alignment-of-airline-partnerships–airport-infrastructure-340603

[8] Australianaviation.com.au, “Australia Signs Open Skies Agreement with China.” Australian Aviation, 2016 https://australianaviation.com.au/2016/12/australia-signs-open-a-skies-agreement-with-china/

[9] Ibid.

[10] International Air Transport Association, “Fact Sheet Worldwide Airport Slots,” IATA, 2018 https://www.iata.org/pressroom/facts_figures/fact_sheets/Documents/fact-sheet-airport-slots.pdf

[11] Kim, S.J., “Government and Industry Officials Talk Aviation Challenges, Regulations.” The Eno Center for Transportation, 2018; “Infrastructure in China: Foundation for growth,” KPMG, 2009 https://www.enotrans.org/article/government-and-industry-officials-talk-aviation-challenges-regulations/

[12] “Infrastructure in China: Foundation for growth,” KPMG, 2009 https://www.kpmg.de/docs/Infrastructure_in_China.pdf

[13] Cheng, A., “Tiny Hong Kong Must Think Carefully before Opening up Its Skies.” South China Morning Post, 2017. https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/2102532/tiny-hong-kong-must-not-overlook-dangers-open-skies

[14] Massy-Beresford, H., “Paris, Hong Kong Airport Operators Ink Cooperation Agreements.” ATW-Air Transport World, 2018. https://atwonline.com/airports-routes/paris-hong-kong-airport-operators-ink-cooperation-agreements

[15] Ocampo, R., “Philippines Signs ASEAN Open Skies Agreement.” TTG Asia, 2017. https://www.ttgindia.travel/article.php?article_id=26650

[16] Business Mirror Editorial, “Yes to the Asean ‘open Skies’ Agreement,” Business Mirror, 2015. https://businessmirror.com.ph/2015/09/23/yes-to-the-asean-open-skies-agreement/

[17] “Vietnam – Aviation,” Export.gov, 2017. https://www.export.gov/article?id=Vietnam-Aviation

[18] Goldman, M., “The Case for an Enhanced and Updated International Air Transportation Policy,” The Air and Space Lawyer, Volume 26, Number 2, 2013; Urs, K.R., “What Comes Next for U.S. International Aviation Policy After 100 Liberalized Air Services Agreements?,” U.S. Department of State, 2011. https://2009-2017.state.gov/e/eb/tra/rm/229214.htm

[19] Cliff Winston, Jia Yan, “Open skies: Estimating travelers’ benefits from free trade in airline services,” Brookings Institution, May 2015. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Open-Skies-Published.pdf

[20] International Civil Aviation Organization, “Antitrust Immunity for Airline Alliances,” Working Paper, ATCONF, Sixth Meeting, March 2013. https://www.icao.int/Meetings/atconf6/Documents/WorkingPapers/ATConf6-wp85_en.pdf

[21] Jeffrey Shane, Warren Dean, “Alliances, Immunity, and the Future of Aviation,” The Air & Space Lawyer, Volume 22, Number 4, 2010.

[22] U.S. Department of State, “Civil Air Transport Agreements,” 2018. https://www.state.gov/e/eb/tra/ata/

[23] Air Carrier Statistics (Form 41 T-100), “International Segment, 2017” Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 2018.

[24] Partnership for Open and Fair Skies, “The Deck is Stacked”, 2018. https://www.openandfairskies.com/subsidies/

[25] Ibid.

[26] Mark Perry, “More on airline industry inconsistencies/double-standards on competition and government subsidies,” American Enterprise Institute, December 8, 2017. https://www.aei.org/publication/more-on-airline-industry-inconsistencies-on-competition-and-government-subsidies/

[27] Aaron Karp, “Yes, Mr. Anderson, Chapter 11 is a ‘government subsidy’,” Air Transport World, February 20, 2015;

“PBGC Takes $2.3 Billion Pension Loss from US Airways,” Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, February 2, 2005. https://atwonline.com/blog/yes-mr-anderson-chapter-11-government-subsidy

https://www.pbgc.gov/news/press/releases/pr05-22

[28] Josh Lederman, “U.S., United Arab Emirates near deal to solve airline subsidy spat, sources say,” Chicago Tribune, April 13, 2018. https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-united-arab-emirates-airline-subsidy-deal-20180412-story.html

[29] CAPA – Centre for Aviation, “US-Gulf airline conflict: peace with (almost) honour,” May 24, 2018. https://centreforaviation.com/analysis/reports/us-gulf-airline-conflict-peace-with-almost-honour-413029