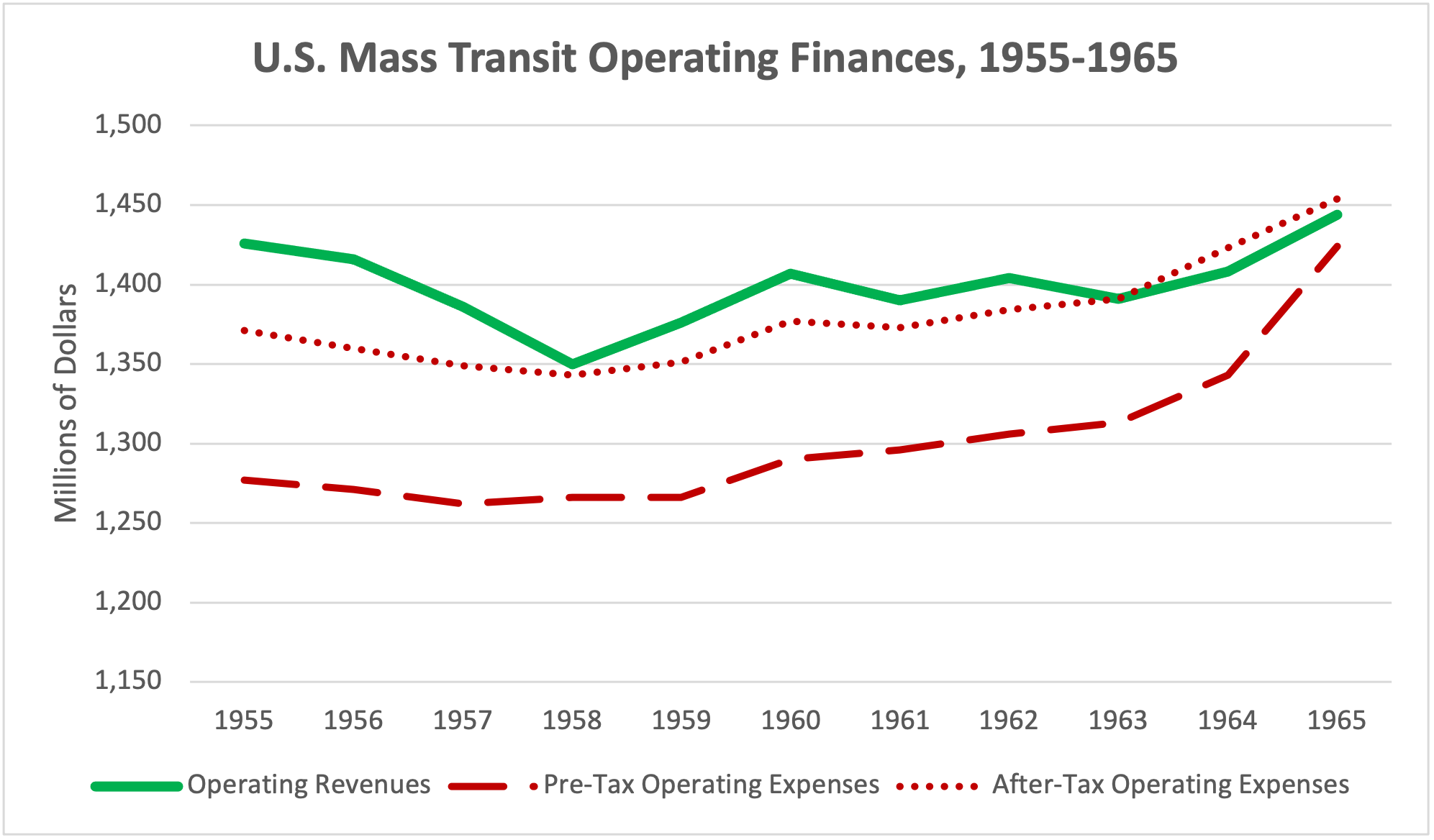

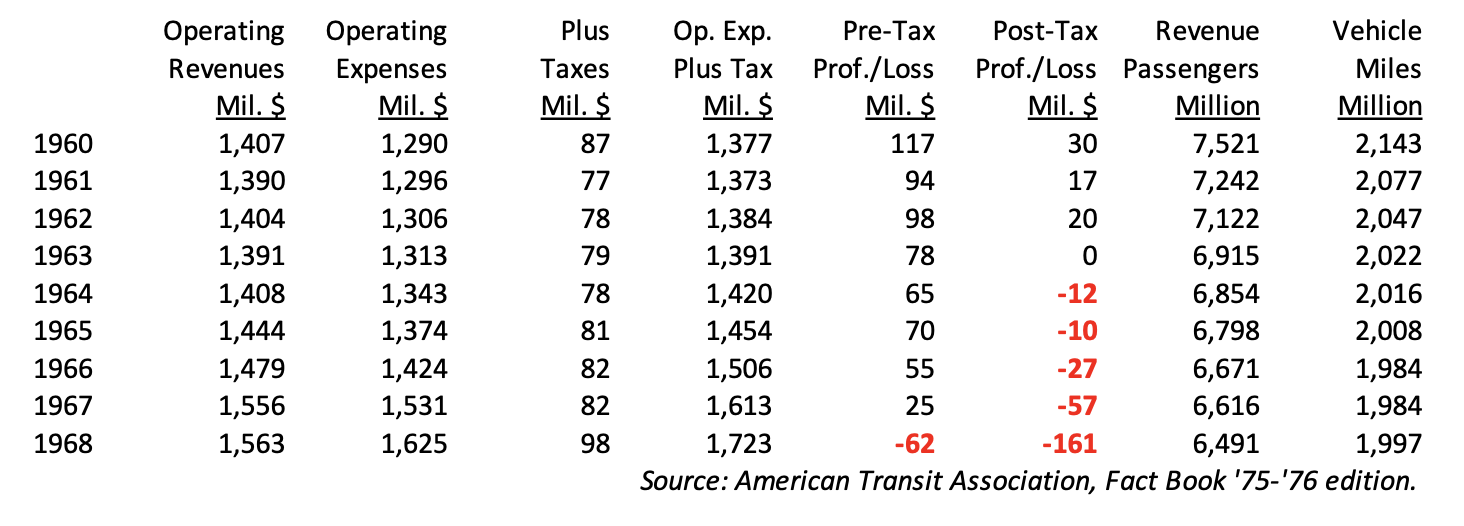

On an after-tax basis, the entire U.S. mass transit sector had ceased to be profitable in 1963. Sharp increases in operating costs meant that the pre-tax side was catching up, and in 1965, the overall total was barely above breakeven.[1] But the privately owned railroads had it worst, and this localized the immediacy of the problem in areas dominated by commuter rail (New York City and other major cities in the Northeast).

1966

Starting in the wee hours of New Years Day 1966, New York City was crippled when its two major transit unions (the TWU and the ATU) went on strike in what was the first large strike by municipal employees in the city’s long history. For years, when the transit unions had asked for more money, city leaders had hidden behind the incremental difficulty of increasing subway and bus fares.

In 1920, subway stations installed turnstile machines that accepted nickels (the base fare from 1904 to 1948). To increase fares in 1948, the city had to alter each machine to accept dimes instead. Then, the 1955 fare increase to 15 cents required all-new machines that ran on new tokens that had to be purchased from station managers.

The TWU reportedly wanted the city to double the price of a token, from 15 cents to 30 cents, and use those proceeds for increased worker pay and benefits.[2]

By the strike’s end on January 12, the union leaders were in jail, the head of the ATU was dying of a seizure suffered while in jail, and the city had a new law that was supposed to make it more difficult for municipal workers to strike. And the transit workers had a settlement that would increase average wages for transit workers by 30 percent. Left uncertain was how, precisely, the city would pay for the increased operating expenses.

Meanwhile, the federal aid program for mass transit capital expenses, established in 1964, was due for reauthorization by Congress later that year. (The original act authorized appropriations for fiscal years 1965, 1966, and 1967.) On January 20, 1966, Senator Harrison Williams (D-NJ), the father of the transit program, addressed the issue on the Senate floor, saying that his original law “was aimed at revamping and remodeling transportation systems which were already paying their own way out of the fare box or were receiving sufficient local subsidies to stay in business.” But:

Unfortunately, we have been somewhat beguiled by the ‘folklore of the fare box’ and have tended to ignore the disconcerting fact that many public transportation systems – buses, subways, and commuter railroads – are simply not meeting their operational costs and consequently are in no position to take advantage of the capital grants under the Mass Transit Act…The commuter problem facing the tristate area of New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut – a problem which has been studied, discussed, analyzed, and argued about for over a decade – merely exemplifies that aspect of the commuter transit problem which we were not yet ready to deal with in the Mass Transit Act, and which is now staring us in the face. Many of the commuter lines – whether publicly owned subways in Boston or New York, privately owned railroads like the New Haven and Reading, or bus systems, simply cannot finance their operations out of the fare box and need immediate and direct cash grants merely to keep their heads above water.[3]

On that day, Williams introduced two bills. The first (S. 2804, 89th Congress) reauthorized the mass transit program for three more years and authorized a new grant program to pay up to two-thirds of the operating deficits of any mass transit provider, for up to 15 years. That was referred to the Banking and Currency Committee. The other bill (S. 2805, 89th Congress) authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to require railroads to make more effort to find a “soft landing” for money-losing commuter routes they wanted to abandon, and that bill was referred to the Commerce Committee. (The text of both bills can be read here starting on page 715.)

The Johnson Administration’s top transportation advisor, Under Secretary of Commerce Alan Boyd, who was otherwise busy in 1966 convincing Congress to create a new Department of Transportation that he would run, told the White House that he did not like Williams’ approach. In a February 9 letter to presidential aide Lee White, Boyd pointed out that the Kennedy Administration had specifically rejected the idea of operating assistance when formulating its transit proposals in 1961 and 1962, and pointed out two general problems with subsidies:

- The size of the Federal payment inevitably gets involved in local labor problems. This is the situation affecting New York City, which subsidizes its subway system.

- A subsidy of an existing system tends to preserve that system as it is and does not encourage cost saving innovations. Vested interests develop in the system which is maintained by the subsidy, and it is difficult to change it.

Boyd then noted that money was the answer, but not operating subsidies:

We might as well face it. The only way that New York and other major metropolitan areas can solve their transit problems is through massive region-wide investment such is contemplated in the Washington area and in San Francisco. If the Federal government is to be helpful in this kind of situation, it must gear its mass transportation program to the nature of the need.

Senator Williams’ bill does not do this. It is a palliative which avoids the main Federal issue.[4]

In April, the Banking Committee formally asked the Johnson Administration for its opinion on the transit subsidy bill. Both the Commerce Department and the new Department of Housing and Urban Development responded. Commerce’s letter was along the lines of Boyd’s earlier internal memo. HUD Secretary Robert Weaver echoed Commerce’s belief that federal operating subsidies prevent local governments from taking “the necessary ‘hard look’” at operations, but also noted “Operating subsidies, and especially those continuing for more than a short emergency period, require very close involvement in the operating details and policies involved in commuter or other mass transportation service. This is particularly true with reference to the establishment of proper fare and wage levels. We consider this an area in which the Federal Government should not become involved. Indeed, we doubt that the localities themselves would wish us to become involved even if they were to receive Federal funds in the process.”[5]

Senate Banking began holding hearings on the Williams bill and other mass transit reauthorization proposals on April 28. The first witness was New York City Mayor John Lindsay, whose first day in office had, not coincidentally, been the first day of the transit strike (what Lindsay jokingly referred to as a 12-day cram course in the relationship between collective bargaining and mass transit operations).

Lindsay cited projections that NYC transit would run a $76 million operating deficit in 1966, but then offered several reasons why they did not want to increase the 15 cent base fare:

First, a fare increase would strike hardest at the more than 1 million New Yorkers who earn less than $4,000 a year. To them, low-cost public transportation is not a bargain, but an essential condition of employment. It enables the low-paid employee to get to his job.

Moreover, it is not commonly recognized that – with a few limited exceptions – New York’s transit system offers no transfers. People who use both a subway train and a bus pay up to 60 cents to get to and from work.

A 25-cent fare sounds reasonable in theory, but in practice it will mean an added expense of $2 a week to those passengers who use both subways and buses each day. Many of those passengers are least able to pay the higher fare…

Second, an increase would drive many passengers away, and the majority of them would turn to automobiles. New York City, I think you will agree, should do everything possible to reduce traffic congestion. A higher fare would have the opposite effect.

Third, even a 25-cent fare would not end the operating loss of the bus and subway system for more than a year and it is highly debatable whether such a fare should be charged at all.

Cheap transportation for its residents is as essential a city service as police protection, welfare assistance, or public education, yet there is no direct charge to the recipient for these established municipal activities. I do not suggest that public transportation be free, but I believe it can be argued forcibly that an economical transportation is as much in the city’s interest as a free school system.[6]

Lindsay endorsed both Williams’s bill and a similar bill introduced later by Sen. Jacob Javits (R-NY) authorizing federal operating subsidies of up to 50 percent of losses, and for only three years instead of 15. Javits himself was there and told the committee “I believe it is the role of the Federal Government to help meet the operating costs of essential commuter service just as the Federal Government spends hundreds of millions of dollars to give aid to other means of transportation, such as the subsidies to airlines and the merchant marine and, of course, the enormous Federal highway program.”[7]

The committee later marked up the transit reauthorization bill and reported an amended “clean” version (S. 3700, 89th Congress). When the Senate took up the reauthorization bill on August 15, Williams summarized the committee’s views and actions on his operating subsidy proposal: “I think it was generally the consensus that it was a worthwhile idea that companies that might be on the brink of bankruptcy or in bankruptcy and on the brink of cessation of service should be helped with this operating subsidy. However, faced with the demands occasioned by the Vietnamese situation and by all other demands, it was the suggestion of my chairman, the Senator from Alabama [Mr. Sparkman], that we postpone this matter for another year to see what the fiscal posture is at that time.”[8]

The Senate passed the reauthorization bill, without operating subsidies, 65 to 18.

While the transit bill was moving through Congress, the mass transit capital funding debate also migrated, for the first time, to the biennial highway reauthorization bill. When the House was considering its bill (H.R. 14359, 89th Congress) on August 11, 1966, Congressman William Ryan (D-NYC) offered an amendment providing that “The Governor of a State may elect to have any [highway] funds apportioned to such State after the date of enactment of this Act…made available…for urban mass transportation purposes, within such State, under section 3 of the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964.”[9] (See the full text on page 19103 here)

Ryan made a case for more even federal funding of mass transit and highways, but the presiding officer (Dan Rostenkowski (D-IL)) upheld a point of order made against the amendment by the Public Works chairman: “This is a highway bill and it does not go to the mass transportation problem. Under the rules, the Chair sustains the point of order of the gentleman from Alabama.”[10] This killed the amendment and prevented it from getting an up-or-down vote.

When the House debated its own mass transit bill (H.R. 14810, 89th Congress) the following week, on August 16, Ryan tried again, offering the exact same amendment allowing states to use apportioned highway funding for mass transit. Again, Public Works raised a germaneness point of order, and again, the presiding officer (this time John Moss (D-CA)), ruled against Ryan:

“The amendment from the gentleman from New York clearly goes to funds covered under title 23. It is within the jurisdiction of the Committee on Public Works, and after carefully examining the rules the Chair is of the opinion that the amendment is not germane. The point of order is sustained.”[11]

The issue of mass transit operating subsidies never came up in the House, which was more skeptical of urban issues generally and mass transit specifically at this time than the Senate. The House then went to conference with the Senate to produce a final transit bill.

The final bill became Public Law 89-562 on September 8, 1966. At the bill signing, President Johnson said “The problem of getting in and out of New York City must be solved not here in the White House in Washington but it must be solved in New York City. This is true for Boston or Philadelphia or Los Angeles. But we can and we will help with funds and with counsel.”[12]

(By that point, New York City had already temporarily solved its transit cash crisis by increasing its base fare from 15 cents to 20 cents, effective July 5, 1966.)

1967-1968

Williams wasted little time the following year in bringing the issue forward. On January 18, 1967, Williams introduced a revised version of his operating subsidies bill as S. 511 (90th Congress). It authorized $75 million per year for five years for operating subsidy grants at a two-thirds federal share, and Williams repeated a version of his “folklore of the farebox” speech from the year before. (Read it, and the bill, here starting on page 859.)

Again, HUD Secretary Weaver sent a letter to the Senate committee opposing the bill. This time, he acknowledged that “there may in some cases be urgent need to provide interim public assistance for commuter service” but “the basic issue is who should provide such interim assistance. We believe it is desirable to continue the present Federal policy of leaving the responsibility for such assistance in the hands of State and local units of government, and limiting Federal action to the area of assisting projects for permanent improvements to mass transportation systems.”[13]

However, the mass transit program had just been reauthorized, so Congress was in no mood to take up any specific mass transit legislation in 1967. The Banking Committees were preparing other housing legislation, and the American Transit Association asked the committees to amend the Mass Transit Act to allow non-governmental transit providers to provide the matching share for federal capital grants, but ATA did not ask Congress to deal with operating subsidies in 1967.[14]

Another reason why there was no significant Congressional action on mass transit in 1967 or 1968 was that New York City, the one locality without which no discussion of U.S. mass transit can be had, was in the process of overhauling its transit governance, revenue structure, and future vision. The result of this process was that, over the course of those years, the New York City Transit Authority (which operated the subway and some buses) had merged with the state entity created in 1965 to take over the Long Island Rail Road, and that new entity also took over operations of the New Haven Line and the Staten Island Rail Road, along with other New York Central commuter trains.

This new state-run Metropolitan Transit Authority also in 1968 took over the authority that ran the NYC bridges and tunnels, ousting Robert Moses, and this had the promise of using car and truck toll revenue to help defray mass transit expenses. At the same time, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central were merging, which had vast implications for commuter rail elsewhere in the Northeast. All of these local developments contributed to the “wait and see” policy at the federal level in 1967-1968.

Speaking of those railroad mergers, Senator Williams did convince the Senate Banking Committee to hold three days of hearings in March 1968 on the problems that railroad mergers were posing for commuters. Williams and some of the witnesses mentioned operating subsidies, but the idea of providing subsidies to for-profit corporations was so beyond the pale that no action was taken.

(At the hearing, after a witness used the phrase “operating subsidy,” Williams said “We don’t use that word any more – ‘subsidy.’ We call it support.”)[15]

In any case, the 1966 mass transit reauthorization law meant that the program did not have to be reauthorized in 1967 or 1968, so Congress did not. The 1967 and 1968 omnibus housing bills each carried a few mass transit provisions, but there was never any consideration of operating subsidies in those bills.

Transit interests were busy trying again to raise the issue of mass transit capital funding in the context of the highway reauthorization bill. The 1968 bill (H.R. 17134, 90th Congress) was going through the House of Representatives on July 3, 1968, and Congressman Ryan once again offered his amendment to allow states to use their highway funding for mass transit capital projects, even though it had been ruled out via point of order twice in 1966 (on the highway bill and on the transit bill).

Once again, Ryan made a strong case for vastly increased mass transit capital funding, and when the Public Works subcommittee chairman raised the germaneness point of order, Ryan brought up his 1966 experience: “We cannot have it both ways. It must be in order in one place or another. The problem is how to get this issue before the House. It seems to me the only way to bring it before the House is to deal with the subject matter with which the bill presently pending deals; that is, the fund out of which money is appropriated to highways. Otherwise there is no way of bringing this issue before the House.”[16]

But Rostenkowski was in the chair again, and he hid behind his own ruling two years prior. The Ryan amendment was thrown out on a point of order. The 1968 highway bill became law without opening up the Highway Trust Fund to mass transit capital spending.

Even though President Johnson had abruptly pulled his name out of contention for re-election on March 31, 1968, the Cabinet Departments continued to produce legislative proposals for the upcoming Congress, particularly for programs which, like mass transit, were due for legislative reauthorization.

In mid-December, 1968, Transportation Secretary Boyd sent the White House a draft mass transit reauthorization bill and detailed explanation. The bill, to be submitted to Congress in early January 1969 before Johnson turned the keys over to Nixon, would double mass transit funding, create a permanent Urban Mass Transportation Trust Fund financed by a portion of the excise tax on new car sales, and make numerous program changes. But the Johnson bill continued to ban federal funds from being used for operating subsidies.

(The Nixon Administration, in 1969, would take up the Johnson transit proposal, make a few changes, and submit it to Congress, but Nixon was even more against a program of dedicated operating subsidies than Johnson had been.)

But, during the three years since Williams had first made his operating subsidy proposal, the finances of the transit industry had gotten worse. The after-tax operating losses for the entire sector had gone from $27 million in 1966 to a $161 million loss in 1968, and the trends were looking worse. Congress was certain to take a closer look at all of the transit funding needs – capital and operating – during the first two years of the Nixon Administration.