November 21, 2017

Automated and connected vehicle technologies are widely anticipated to improve the safety and efficiency of cars and trucks, but have also raised serious questions around automotive cybersecurity. A widespread hack could effectively negate both of these benefits by rendering vehicles permanently inoperable (“bricking”) or, even worse, force widespread vehicle collisions.

In many ways, competition in the auto industry is like chess: manufacturers must stay several steps ahead of their competitors by planning their next moves well in advance while also achieving short-term wins in the market to maintain their foothold.

But automotive cybersecurity, like foreign policy, is more of a game of three-dimensional chess: manufacturers must ensure that each new feature they introduce does not create new vulnerabilities that can be exploited from any angle. From a purely technological standpoint, this is a daunting task: manufacturers must not only examine each and every component in a vehicle to identify potential vulnerabilities, but the interactions between every component and then the functions of the vehicle as a whole.

Simply reducing risk during production is not enough. Manufacturers must also be agile in responding to threats by constantly searching for, and fixing, vulnerabilities in vehicles once they are on the road. The difficulty continues to mount with each model year as automakers introduce new features that are designed to make driving safer, more comfortable, and more convenient.

On its face, it would seem that the federal government could best address these significant risks to safety, privacy, and economic productivity by approaching them as a national security threat. But while there is an important role to play for the federal government, including the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the speed of innovation in the auto industry necessitates a similarly agile federal approach.

A recent report from the R Street Institute (RSI) explores the challenges of automotive cybersecurity as well as the roles of public and private sector entities in protecting consumers. While the federal government and the auto industry already collaborate to minimize vulnerabilities and respond to threats, RSI provides actionable recommendations that the federal government can take to augment automakers’ cybersecurity efforts.

“For leaders in both industry and government, the challenge is determining how to enable the many economic and environmental benefits of connected and autonomous vehicles without endangering public safety or consumer confidence,” writes RSI. “For this reason, effectively deploying and adopting intelligent vehicles will require continuous, risk-based technological development and a flexible regulatory environment.”

The takeaway: auto cybersecurity is best advanced through an active partnership that combines the strengths of the tortoise – deliberate government action – with the hare – industry agility and innovation.

Understanding Vehicle Cybersecurity

First, it is important to understand what automotive cybersecurity is and how vulnerabilities are created.

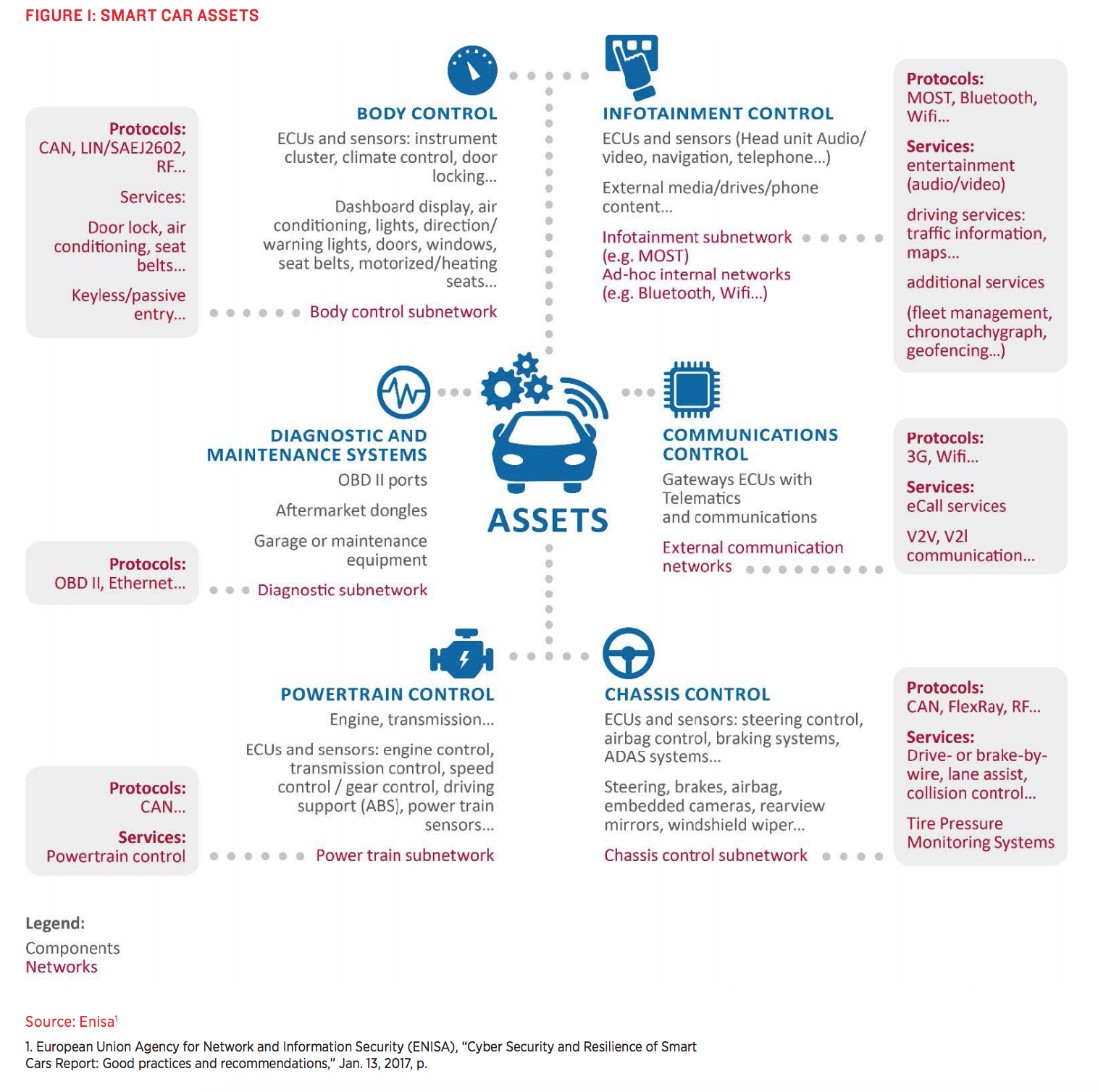

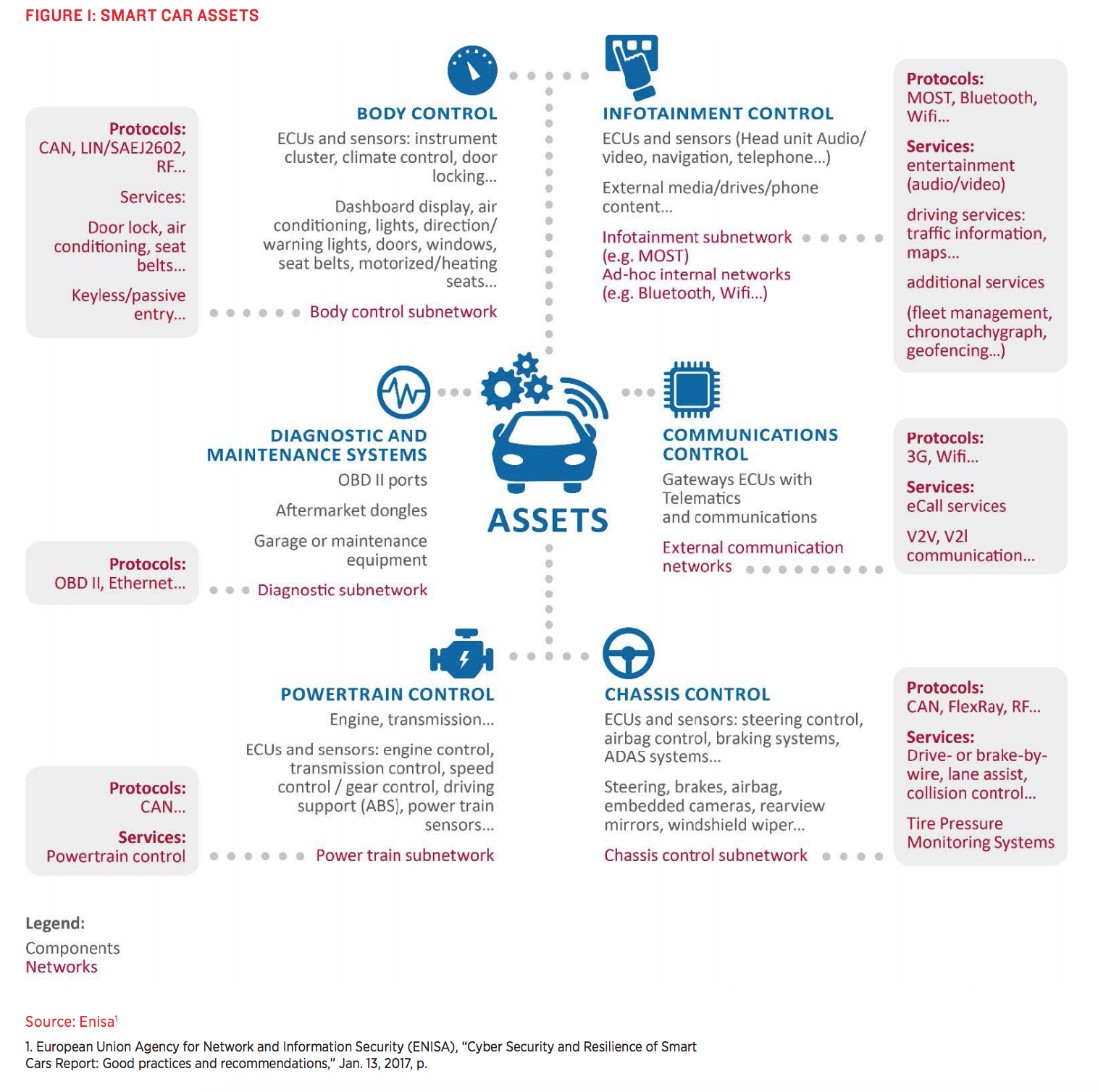

A wide range of electronics contributes to the operation of practically every feature of a car, from acceleration and steering to climate control to diagnostics. These electronic systems will only become more critical as automated vehicle (AV) and connected vehicle (CV) technologies increasingly shift control of cars from human drivers to automated systems.

For this reason, RSI says, “instead of thinking of a connected or autonomous vehicle as a single, undifferentiated cyber target, it is important to recognize that each of these components can also be at risk, and with a variety of related safety, security or privacy concerns.”

(Source: R Street Institute)

In prior years, manufacturers used a single component to connect every electronic device in a vehicle, known as the controller area network (CAN). This created a massive vulnerability, as the compromise of one subsystem (e.g., infotainment) could allow other subsystems in the car to be accessed (e.g., steering and acceleration controls). For this reason, automakers have started to silo subsystems from one another to ensure that one component being compromised would not allow for a domino effect of compromised systems across the vehicle.

RSI identifies two broad methods by which a vehicle’s systems can be compromised.

The first is through local attack vectors, which require a hacker to have physical access to the electronic components of a vehicle through USB ports, onboard diagnostic ports (OBD-II), or charging stations used by electric vehicles. The scale of these types of attacks would likely be less severe, since hackers would have to gain access to the individual vehicles.

The second method, which could be significantly more severe at scale, is through remote attack vectors that target a vehicle’s external communications systems. This could include exploiting vulnerabilities in a connected vehicle that uses dedicated short-range communications (DSRC) or cellular communication (5G/LTE).

As RSI notes, there have already been a number of high-profile hacking incidents. One of the most notable was in 2015, when security researchers were able to remotely control a Jeep Cherokee’s steering, acceleration, and other functions by hacking into its entertainment system. This caused Chrysler to respond by a total of 1.4 million cars.

Improving Cybersecurity

“For the countless companies developing this technology, a public relations nightmare lurks behind every alleged hack and every vehicle collision, irrespective of who is actually at fault.” –R Street Institute

Despite the complexity of these issues, automakers and government leaders have all seemed to land on a single guiding philosophy in cybersecurity: the industry should not make the same mistake twice.

Individually, manufacturers are taking steps to reduce vulnerabilities in the construction and design processes by limiting the potential impact of any hack. But this effort does not end when the vehicle is put on the road – AV manufacturers like Waymo are now introducing backup systems (redundancies) that will pull a vehicle to the side of the road if it detects that the vehicle’s primary system has been compromised.

In addition, automakers have started to offer “bug bounty” programs that pay white-hat hackers who are able to proactively identify vulnerabilities and disclose them to the automaker.

The industry has also started to collaborate and share information when they discover potential vulnerabilities, threats, and successful hacks. The Automotive Information Sharing and Analysis Center (Auto-ISAC), for example, acts as a clearinghouse for manufacturers that represent 99 percent of light-duty vehicles on the road in North America.

Government Initiatives

To date, the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) has taken the lead on cybersecurity issues in transportation, while DHS has played a supporting role by issuing guidelines. However, the federal government has largely taken an advisory approach to cybersecurity in the transportation sector.

This is because setting prescriptive standards would be counterproductive: if every manufacturer were to approach cybersecurity in the exact same way, hackers could consult the standards to discover precisely which defense mechanisms are employed in every vehicle and exploit a single flaw – potentially with nationwide impacts.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) acts as the primary regulator of all aspects of motor vehicle design, construction, and performance in the United States, including cybersecurity. Under the Obama Administration, NHTSA released a guidance document for automotive cybersecurity, titled Cybersecurity Best Practices for Modern Vehicles, in October 2016. The guidance provided recommendations and best practices for manufacturers as they defend against and respond to cybersecurity threats.

For reasons noted above, NHTSA has not issued Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) pertaining to cybersecurity, opting instead to allow manufacturers to take their own varied approaches to minimizing risk. Moreover, setting FMVSS is a grueling and burdensome process that typically requires several years to complete from start to finish, making it supremely ineffective method for responding to imminent threats to public safety.

Future Cybersecurity Policy

“While the current regulatory framework adequately covers many of the existing risks, there is room for improvement and a robust, open and coordinated effort is necessary in order to realize the potential of connected cars.” –R Street Institute

While the advent of AVs and CVs certainly pose new technical challenges for NHTSA and the auto industry, RSI suggests that NHTSA’s existing authorities can be adapted and leveraged to reduce potential risk. The report provides three specific steps that NHTSA can take to assure policymakers and consumers that these emerging technologies do not pose an undue risk to the public:

- NHTSA could require manufacturers to submit detailed answers to questions about their cybersecurity plans, redundancies and layered defenses in the vehicles, how the vehicle will perform if it is attacked, and the types of attacks they can defend against.

- NHTSA can make public the nonsensitive and nonconfidential information from manufacturers’ responses to the questions noted in step one. Proprietary information and privileged information should be redacted.

- NHTSA would then selectively test each of the manufacturers’ claims in a similar manner as it currently tests vehicles for FMVSS compliance through its post-market oversight authority. If NHTSA finds that a manufacturer misrepresented their cybersecurity capabilities, it could use its existing recall authority to rectify the issue.

Through this approach, NHTSA would continue to have an active dialogue with industry officials without requesting additional authorities from Congress – an effort that would continue to encourage cooperation between the public and private sector on cybersecurity matters while building consumer confidence in automated and connected vehicle technologies.

The full report, Addressing New Challenges In Automotive Cybersecurity, can be downloaded on R Street’s website.