Yesterday, the full House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee held a hearing titled “Assessing the Federal Government’s COVID-19 Relief and Response Efforts and its Impact – Part II.” (Part I, from July 29, is here.)

Witnesses included:

- Paul P. Skoutelas, President and CEO, American Public Transportation Association (APTA)

- Juan Ortiz, Director for the Office of Emergency Management & Homeland Security City of Austin, Texas

- Michael J. Boskin, T M. Friedman Professor of Economics, Stanford University

- Wendy Edelberg, Director, The Hamilton Project, The Brookings Institution

- Greg Regan, President, Transportation and Trades Department, AFL-CIO

Because two witnesses were economists, a good potion of this hearing was directed at their expertise. Boskin’s opening statement and T&I chairman Peter DeFazio’s (D-OR) following line of questioning showed sharp divides in economic theory regarding infrastructure: Boskin claimed that every dollar invested in infrastructure gives a return of only 60 cents. DeFazio questioned these numbers, as last year S&P produced a report stating that there is a $2.70 return for every dollar spent on infrastructure, and other research indicates even higher returns.

There was some criticism, in varying degrees, by Republicans of the infrastructure bill and reconciliation package. While some like Rep. Rick Crawford (R-AR) were extremely critical, saying the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan “masqueraded” as COVID relief but was really Pelosi priories, others critiqued the infrastructure bill because it was written by 20 Senators and was never put through the Committee which was supposed to write it (something at which DeFazio has also expressed frustration). Others took a more inquisitive approach to funding infrastructure investments: they were not against it but wanted to know that transit agencies were in need of the funds and would invest it wisely.

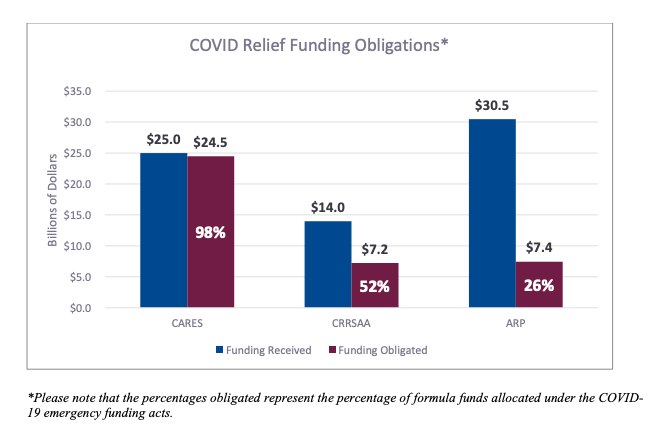

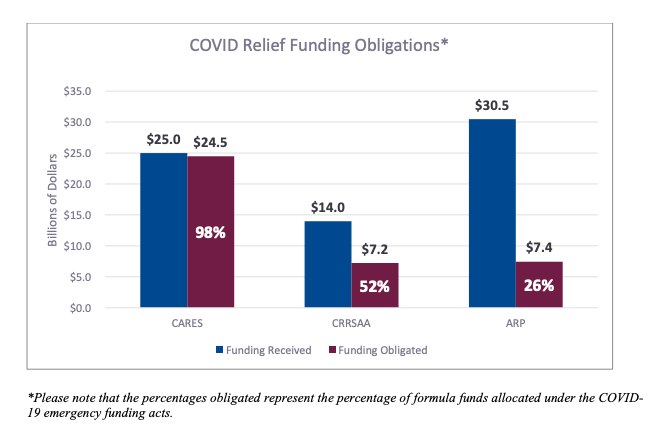

The hearing was intended to examine COVID relief funding, most of which was intended to help transit agencies cover operating expenses on an emergency basis. Only Section 3401(4) of the American Rescue Plan included a small amount of funding solely for capital projects. Emergency funding from Congress, like the COVID money, generally implies urgent and immediate need. Skoutelas told the committee that 56 percent of the total amount of COVID emergency funding that had been provided via formula to transit providers has already been obligated. (This means that the agency has applied for the money, told USDOT their plan for using the funds, and had the money legally released to them.) This totals about $39 billion of the $69.5 billion provided, but it varies by which COVID relief bill is being discussed:

However, the overall role of the federal government in investing in capital infrastructure was a frequent topic of discussion. For example, the California High Speed Rail (CAHSR) project was mentioned frequently as an example of wasted federal dollars: many Republicans used this project as an example of why so many transit projects are unsuccessful. And make no mistake – CAHSR has been a crash course in how not to manage a megaproject. But even Boskin conceded that it is an unusually badly governed project, and that there are much better examples of projects that are delivered on time and on budget (for more information on this, see our Saving Time and Making Cents: A Blueprint for Building Transit Better report). While it was mentioned frequently in the context of the broader role of government in transit funding, no COVID funding went to CAHSR.

One aspect Boskin and Skoutelas agreed on, though, was the need for maintenance and repair of existing transit systems. To Boskin, this is a worthwhile investment as it has high cost-benefit ratios and good returns. Skoutelas spoke at length about the state of disrepair of U.S. transit systems, arguing that it is essential to pass the bipartisan infrastructure bill to bring these systems up to a state of good repair. APTA is a strong proponent of modernizing transit systems, arguing that it is an appropriate role for the federal government to help pay for this maintenance backlog: while transit agencies can recoup some operating fees from farebox revenue, they often don’t have enough money to finance system renewals with only local and state funding.

Regan and Skoutelas spoke at length on the labor implications from the COVID packages. Regan argued that COVID funding not only helped transit operators keep employees on the payroll when ridership dropped by 90%, but it also kept transit running to accommodate for the essential workers, employed in places like hospitals and grocery stores, that relied on transit to get to work. The three relief packages, said Regan, gave airlines, Amtrak, and transit operators funding for employees, on the condition that they would not furlough any workers: something Regan claimed as a massive win for labor as funding was directed toward the workforce.

This hearing showed the two competing viewpoints on the need to invest in infrastructure, with each having data to back them up. For example, Rep. Randy Weber (R-TX) cited a study that shows the U.S. near the top of global standards, recently ranked 13th out of 143 nations in overall infrastructure. However, Edelberg, Ragan, and Skoutelas offered a much different perspective: all agreed that the U.S. has consistently underinvested in transit. This is why, as Skoutelas point out, the American Association of Civil Engineers ranked U.S. transit as a D- in 2021. In general, this hearing often discussed operating versus capital expenditures in the same way, although the vast majority COVID packages was intended to fund operations. However, all found middle ground in their frustration that the Senate bill as disregarded T&I as a committee, as well as the want for capital projects to be more effectively managed.