Part 1 of this look back at the September 1959 Highway Trust Fund bailout and contemporaneous motor fuels tax increase revealed how the occasional temporary insolvency of the Trust Fund was always assumed in the 1956 law that funded construction of the Interstate System and established the Trust Fund. That article then examined how Congress and the President chose to accelerate and worsen that insolvency by increasing spending in 1958 to respond to a sudden economic recession.

In part 2, below, we look at how President Eisenhower decided to ask Congress to increase gasoline and diesel taxes by 50 percent in order to keep the Trust Fund solvent, and just how negatively Congress, state governments, and highway stakeholder groups received the proposal. Part 3, next week, will tell the story of the endgame.

(In this article we say “gasoline tax” or “gas tax” for short but we are really talking about identical taxes on gasoline and on diesel fuel. But the use of diesel fuel to power vehicles in the U.S. was really a post-WWII phenomenon and at this point diesel use was still de minimis. In 1949, 75 gallons of gasoline were used on highways for every gallon of diesel. By 1959 this ratio was still 24 to 1. In the first three years of the Highway Trust Fund (FY 1957-1959), the Trust Fund had collected $4.6 billion in gasoline taxes versus only $131 million from an identically sized tax on diesel fuel.)

The decision to request a 50% gas tax increase.

Two months after President Eisenhower signed the 1958 highway bill into law, suspending the “Byrd Test” pay-as-you-build Highway Trust Fund solvency guarantee for fiscal years 1959 and 1960 and increasing highway spending to fight a recession, the Secretary of Commerce wrote to the Treasury Secretary on June 23, 1958 to ask for earlier-than-usual access to projected Trust Fund tax receipts. Treasury responded on July 2 to say that the timeframe that Commerce wanted would not allow for them to get the final estimates (Commerce wanted the January 1959 budget numbers by October 15, 1958) but said they could meet that deadline with tentative numbers.[1]

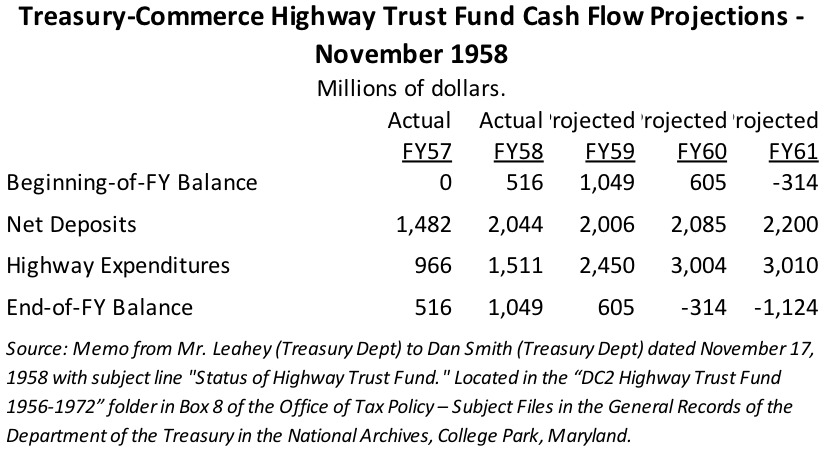

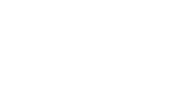

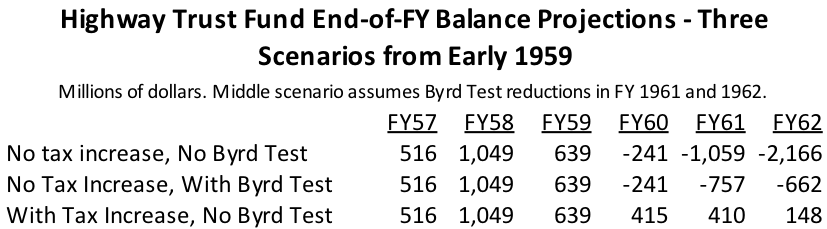

On October 15, Treasury sent Commerce updated Trust Fund tax receipt estimates, which projected that FY 1959 net receipts would be slightly less than FY 1958 ($2.020 billion versus the previous year’s $2.026 billion) and that receipts would rise slightly to $2.085 billion in 1960.[2] By November 17, 1958, a slightly refined version of those receipt projections had been married to Commerce Department estimates of expenditures and the resulting prediction was a $314 million shortfall in the Trust Fund for fiscal year 1960, ballooning to a $1.1 billion shortfall in FY 1961 (assuming that the Byrd Test was waived once again for 1961).

The Eisenhower Administration’s willingness to raise the gas tax to fill any HTF revenue gaps once the 1957-1958 recession was over, expressed by the President himself at multiple behind-the-scenes meetings throughout 1958, had become an open secret. The head of the American Automobile Association wrote to the Treasury Secretary on November 19, 1958 to say that “proposals are being advanced for a Federal gasoline tax increase of 1 to 1 & ½ ¢ per gallon” and that AAA “is strongly opposed to any increase in gasoline taxes.” The letter cited a resolution passed at the most recent AAA annual meeting urging that the funding for HTF solvency come from general revenues and be charged to the defense budget (since a major justification of the Interstate system was its contribution to national defense).[3]

In addition to the immediate short-term cash shortfall, the Interstate program had developed a long-term problem. A preliminary cost estimate update delivered to Congress in January 1958 had shown the long-term cost of completing Interstate construction ballooning from the original $25 billion to $34 billion. Policymakers were divided as to whether or not to fund this cost increase promptly, or else wait for the massive cost allocation study to be delivered to Congress in January 1961 and deal with cost increases and revenue re-allocation at the same time.

On Tuesday, November 25, 1958, the Secretary of the Treasury, Robert Anderson, and his Under Secretary for Monetary Policy, Julian Baird, walked two blocks down 15th Street to the Commerce Department where they met with the new Acting Secretary of Commerce, Lewis Strauss (Secretary Sinclair Weeks had resigned on November 10 because of his wife’s ill health, which had kept him away from Washington quite a bit in 1958). According to Treasury’s summary of the meeting, the two Secretaries decided to deal with the Highway Trust Fund in the upcoming FY 1960 budget request (to be released in January 1959) in the following way:

- “To suspend the Byrd amendment for apportionments to be made for the fiscal years 1961 and 1962.

- “To increase, effective July 1, 1959, the tax on gasoline and diesel fuel by one cent per gallon.

- “As was proposed in the January 1958 Budget Document, to exclude aviation gasoline from the Highway Trust Fund.

- “As was proposed in the January 1958 Budget Document, to charge forest highways and public land highways to the Highway Trust Fund.”[4]

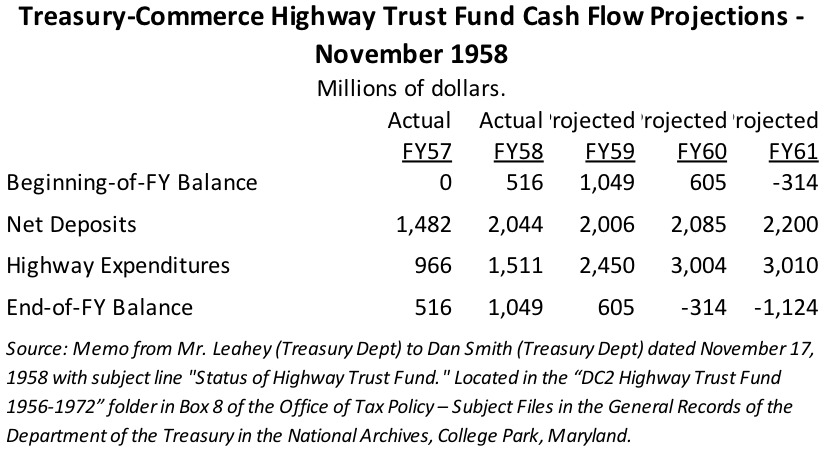

The tax increase was only to be effective for two years (fiscal 1960 and 1961), and Commerce and Treasury agreed to defer consideration of increasing Interstate funding to match the levels in the revised cost estimate until after the January 1961 delivery of the cost allocation study.

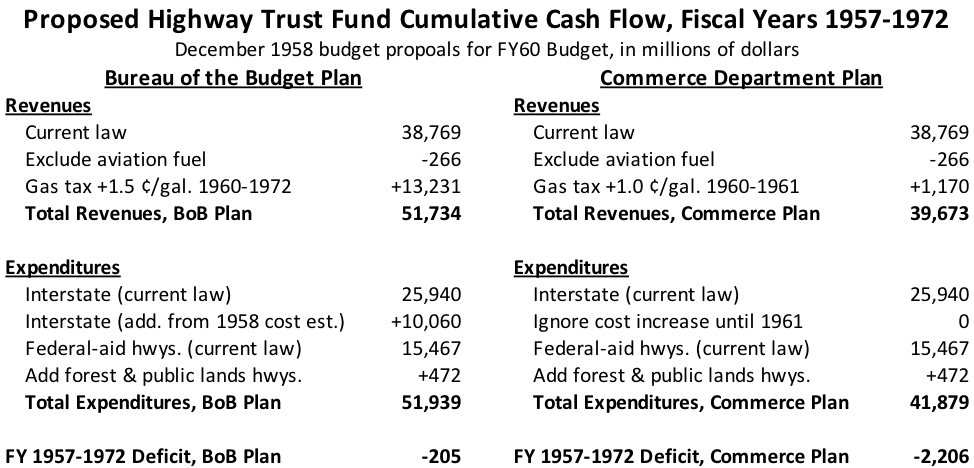

The White House Bureau of the Budget had a much different idea. They proposed to fix the immediate cash shortfall and the long-term cost escalation problem both at the same time, in the FY 1960 budget. Their proposal called for an immediate 1.5 cent per gallon gasoline and diesel tax increase, to last the entire planned duration of the Highway Trust Fund (13 more years, from FY 1960-1972). This would solve not just the short-term revenue shortfall caused by the 1956 Act and accelerated by the 1958 Act but would also take care of the new cost increase. Both the Budget plan and the Treasury plan would include the carryover provisions from the FY 1959 budget to exclude aviation gasoline from the Trust Fund and to charge forest and public land highways to the Trust Fund (proposals that Congress had ignored).

A Budget memo summarized that “Commerce’s proposal is a temporary stop-gap measure and does not meet the requirement for a long-range self-financing highway program…We believe that accepting the temporary expedient proposed by Commerce would establish a precedent for delaying the restoration of the program to a self-financing basis and ultimately result in the diversion of general fund revenues.”[5] The memo also pointed out that “The Commerce proposal which places a lighter burden on the general public would be subject to slightly less opposition; however, opposition will exist against any proposal for a fuel tax increase.”

The Commerce Secretary and the Budget Director met on December 1, 1958 to figure out the minimum revenue (tax level and duration) needed to satisfy several different policy options.[6] But the head of the Bureau of Public Roads his own idea. Bertram Tallamy, the Federal Highway Administrator, prepared a draft letter to be sent to the Bureau of the Budget dated December 11, 1958 proposing that the Treasury issue special bonds to be guaranteed by the Highway Trust Fund and its excise taxes – not general revenues – which would be exempt from the limit on the public debt and which would be repaid out of post-1972 extended HTF tax revenues.[7] It does not appear that the Commerce front office allowed this letter to be sent to Budget at that time (as will be made evident later in the narrative).

The result of the December 16 Cabinet meeting to finalize budget proposals was that the President agreed with Commerce that the issue of finding an additional $10 billion to cover the increased cost estimate for construction of the Interstates would be shelved for another year. But he sided with Budget that the Byrd Test pay-as-you-go provision should not be waived again, and this meant that he also went with the Budget recommendation of a 1.5 cent per gallon fuels tax increase (the minimum needed to allow the full authorized FY 1961 and 1962 apportionments). The President also chose to limit the duration of the 1.5 cent per gallon tax increase to five years (FY 1960-1964) – less than Budget had wanted, but three years more than Commerce had wanted.

Meanwhile, the recession had ended – the January 1959 Economic Report of the President (being prepared during this time) would estimate that “A recovery began in May 1958”[8] and the Joint Economic Committee would soon thereafter estimate that the national Gross Domestic Product would rise from $438 billion in calendar 1958 to $473 billion in calendar 1959.[9] The economy was clearly strong enough to withstand modest tax increases.

On December 22, President Eisenhower released a public announcement that his Administration would be submitting a request for a balanced federal budget the following month “in the general area of $77 billion” and that “The Budget will request increased receipts from higher postage rates and gasoline taxes, and some new user charges for Government services, but will not call for a general tax increase.”[10]

The fiscal 1960 federal budget was released on January 19, 1959. The President’s message said:

“In order to make highway-related taxes support our vast highway expenditures, excises on motor fuels need to be increased 1½ cents a gallon to 4½ cents. These receipts will go into the highway trust fund and preserve the pay-as-we-go principle, so that contributions from general tax funds to build Federal-aid highways will not be necessary.

“At the same time, to help defray the rising costs of operating the Federal airways, receipts from excises on aviation gasoline should be retained in general budget receipts rather than transferred to the highway trust fund. The estimates of budget and trust fund receipts from excise taxes reflect such proposed action. They also include a proposal to have users of the Federal airways pay a greater share of costs through increased rates on aviation gasoline and a new tax on jet fuels. These taxes, like the highway gasoline tax, should be 4% cents per gallon. I believe it fair and sound that such taxes be reflected in the rates of transportation paid by the passengers and shippers.”[11]

The proposed 50 percent increase in gasoline and diesel taxes was to last for five years – from July 1, 1959 to June 30, 1964 – and was projected to bring in an additional $689 million in gross tax receipts in fiscal 1960, on top of the $2.2 billion in projected gross receipts under existing law. In FY 1961, it would bring in an extra $884 million, and in FY 1962, an extra $919 million. (The transfer of aviation gasoline tax receipts out of the HTF would cost $34 million in 1960, which was already added into the totals above.) And the budget again proposed to fund forest and public lands highways out of the Trust Fund, which would have increased expenditures by $41 million in 1960.

Overall, the proposed budget was in balance, with $77.10 billion in anticipated receipts versus $77.03 billion in expected on-budget expenditures, assuming of enactment of the Administration’s proposed spending and revenue policy changes. But these totals did not mean then what they mean today. There were two major differences from today in the budget process in use in 1959 which play a major part in the rest of the narrative.

How the federal budget was different in the 1950s.

Trust funds were effectively “off-budget.” In terms of budget presentation, federal budgets between FY 1936 and FY 1970 used the “administrative budget” as its primary presentation. This excluded transactions with federal trust funds (Highway, Social Security, Unemployment, etc.) and with government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). Although other presentations were stuck in the back of the budget document, “Fiscal policy tended to focus on the administrative budget.”[12] Trust funds were expected to add an additional $20.48 billion in tax receipts and $20.26 billion in expenditures to those $77 billion FY 1960 budget totals. For example, projected Commerce Department expenditures for 1960 as part of the administrative budget (what we would now call “on-budget”) were only $476 million – but if you looked in the back of the book where the trust funds were listed, you would see an additional $3.136 billion in projected Highway Trust Fund spending, meaning that about 87 percent of Commerce Department spending was not part of the regular budget.

This also meant that transactions between the general fund and a trust fund showed up as part of the budget just like transactions between the general fund and non-government entities. A repayable advance from the general fund to the HTF (as authorized under the 1956 Act) would look just like an appropriation directly to a state, a company, or a foreign government. And the diversion to a trust fund of any existing tax that was being deposited in the general fund would look just like a net federal tax cut.

The federal fiscal year started July 1, not October 1. The 1974 Budget Act moved the start of the federal fiscal year from July 1 to October 1, effective with fiscal year 1976. But in the 1950s, as today, the busiest spending months for the federal-aid highway program were August and September of each year – the months where both warm-weather states and cold-weather states were busiest building and upgrading roads. (July and October are almost always the 3rd and 4th most high-spending months, though not always in that order.) Highway Trust Fund tax receipts have never shown nearly that much month-to-month variation.

This means that in the 1950s and 1960s, the Trust Fund ran its biggest cash deficits at the beginning of the fiscal year, not the end of the year. Today, it runs its deficits at the end of the fiscal year (and the first month, October, which has a retroactive tax credit thing going on nowadays) and then catches back up in the winter months. But back then, monthly deficits were front-loaded. Accordingly, a bailout, if any, would be needed early on in the fiscal year, not later. But it made it much more likely that a small bailout transfer made early in a fiscal year could be completely repaid, with interest, by the end of that fiscal year.

Congress, governors react negatively.

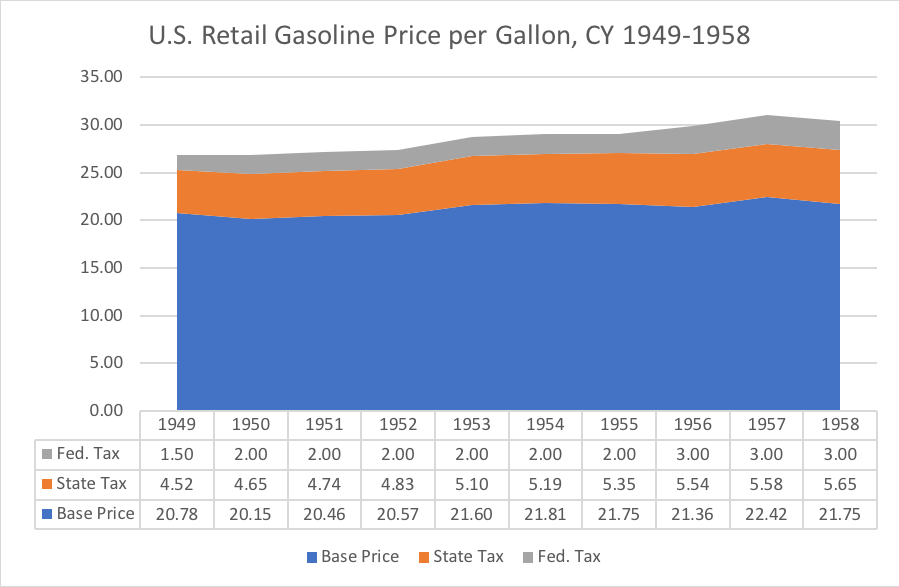

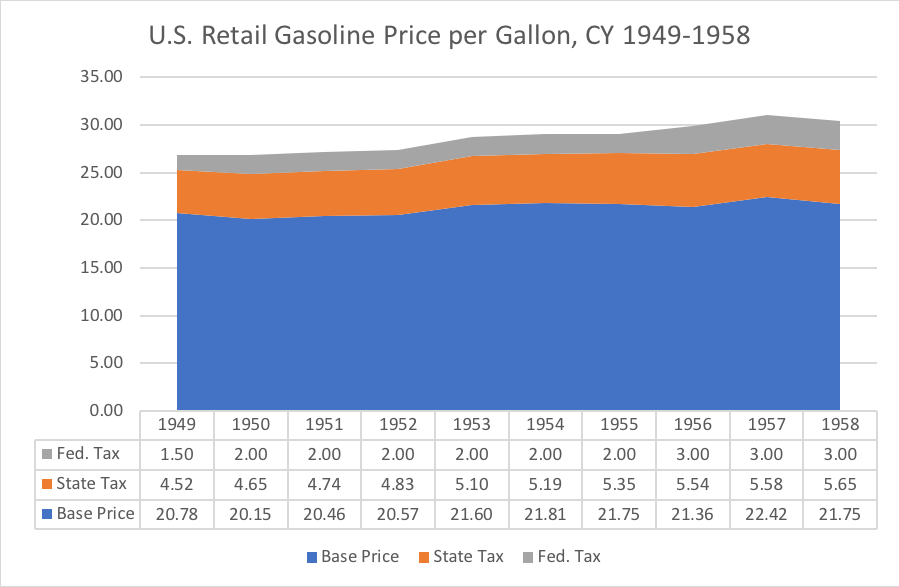

An extra 1.5 cents per gallon was a much bigger deal, percentage-wise, in January 1959 than it is today. An extra 1.5 cents would mean the federal tax on gasoline would have tripled in 10 years – it was 1.5 cents per gallon in 1949 before rising to 2.0 cents in 1950 and thence to 3.0 cents in 1956. The average state tax rate had gone up more slowly, from 4.5 cents per gallon (weighted average) in 1949 to 5.7 cents in 1958. And the base price of gasoline, excluding taxes, had been remarkably steady – 20.8 cents per gallon in 1949 to 21.8 cents per gallon in 1959.

In particular, state governments were positioned to oppose extra federal gasoline taxes, as they saw every extra penny of federal gasoline tax making it more difficult for them to go that same revenue source for any future highway funding increases. The governor of Texas, Price Daniel (D), sent telegrams to the other 47 state governors on January 12 asking them to oppose a federal gasoline tax increase and instead ask for other highway user taxes, like the tax on automobiles (see below), to be deposited in the Highway Trust Fund instead. By January 25, Daniel told the Associated Press that he had 28 favorable replies from other governors versus only seven negative replies, He cited the Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Virginia and West Virginia governors joining him in opposition to the tax increase.[13]

The Associated Press ran a story that hit newspapers across the country the day before the budget came out interviewing the new chairman of the Senate Public Roads Subcommittee, Pat McNamara (D-MI), who said that his state government and many others opposed a federal gas tax increase because “The states must rely on the gasoline tax for their road financing, and they don’t think the federal government should add anything to the load.”[14]

There was not an immediate groundswell in support of the President’s proposed fuels tax increase – quite the opposite. On the day after the budget’s release, House Speaker Sam Rayburn (D-TX) told reporters that he had strong doubts that the gas tax increase would pass Congress.[15] Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson (D-TX) criticized the budget on the Senate floor that day, saying “Far from opening the way to tax cuts, this budget proposal would open the way to imposition of more and more sales taxes – sales taxes, first, on gasoline; sales taxes then, on other essentials; and finally, I believe, sales taxes would come on everything. I, for one, am unwilling to travel this road. This administration has demanded that local governments pay more of local costs. Now it proposes to enter a footrace with the States and the cities, to see who can preempt the gasoline tax first as a source of revenue.”[16]

Minority Whip Thomas Kuchel (R-CA) took issue with Johnson’s remarks, interrupting him to note that it was the Democratic Congress that forced the 1956 gas tax increase on Eisenhower when it rejected the borrowing plan to finance Interstate construction recommended by the Clay Committee.[17] This exchange was also written up in national newspapers.

And the opinions of Rayburn and Johnson mattered more in 1959 than they had in 1958 – in the 1958 elections, before the recovery from the recession had become visible, Democrats gained 14 seats in the Senate (from a 50-45 margin with one vacancy at the end of 1958 to a 64-34 margin at the start of 1959). And Democrats gained 50 seats in the House, from a 232-193 margin at the end of 1958 to a 282-153 margin at the beginning of 1959. Numerically, this was by far the most hostile Congress Eisenhower had faced.

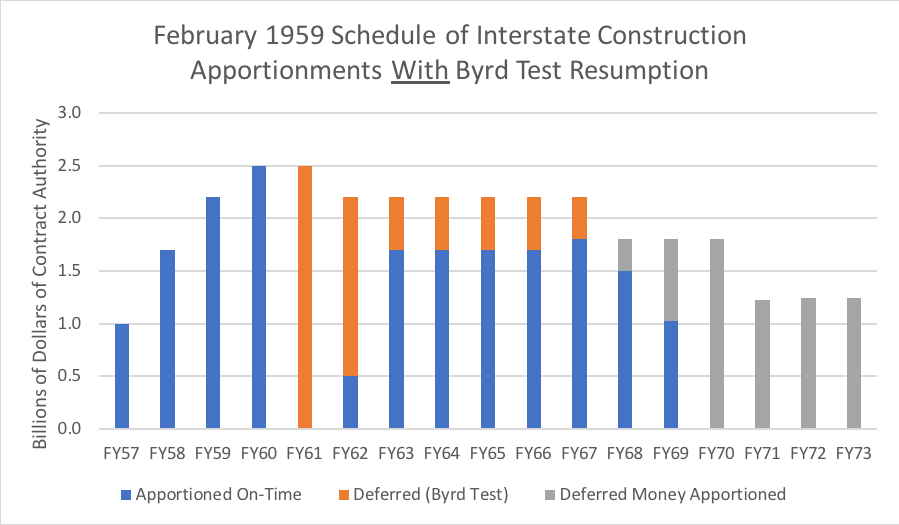

The Administration says zero Interstate funding for FY61

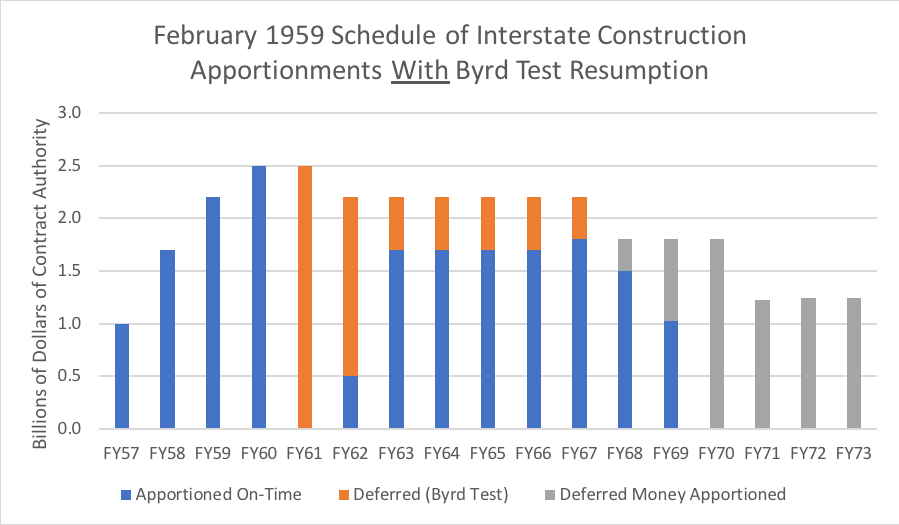

But without prompt revenue increases, or “repayable advance” appropriations from the general fund, the Interstate program would face an immediate shutdown of new funding by August 1959 (when the fiscal 1961 apportionments were supposed to be made). At a February 1959 hearing of the Senate Public Works Committee, the Bureau of Public Roads laid out the hard facts: the resumption of the Byrd Test would mean zero new Interstate Construction funding apportioned to states for FY 1961 (the entirety of the authorized $2.5 billion would be deferred), and $1.7 billion of the scheduled $2.2 billion in FY 1962 apportionments would also be deferred. In total, the Byrd Test would defer $6.6 billion of IC apportionments over the 1961-1967 period and then add it back over 1968-1973 (except the Trust Fund and its dedicated taxes were set to expire before that, so the final $2.5 billion in apportionments in FY 1972-73 were unfunded). BPR submitted a table at the hearing[18] that we have replicated in color:

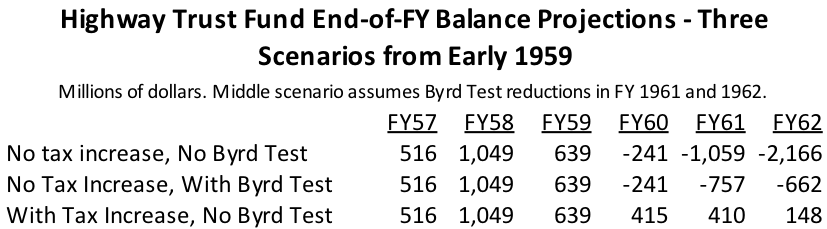

And even with new 1961 Interstate apportionments zeroed out, the Trust Fund was still going to run out of money in 1960 and dig the hole deeper in 1961 because of slow-spending, prior-year obligations. On March, 2, 1959, the Treasury Department sent Congress the annual HTF status report, which had a slightly different set of Trust Fund cash flow projections from those in the budget – while the budget showed projected cash flow through 1962 both with and without the tax increase, the budget assumed that the Byrd Test would not be triggered in 1961 or 1962. The Treasury report contained numbers based on a different assumption – that the Byrd Test would be triggered and reduce apportionments every year starting in 1961, but that wouldn’t be enough to prevent a default (in the absence of a tax increase) because so many inflated bills incurred with 1959 and 1960 apportionments would be coming due.[19]

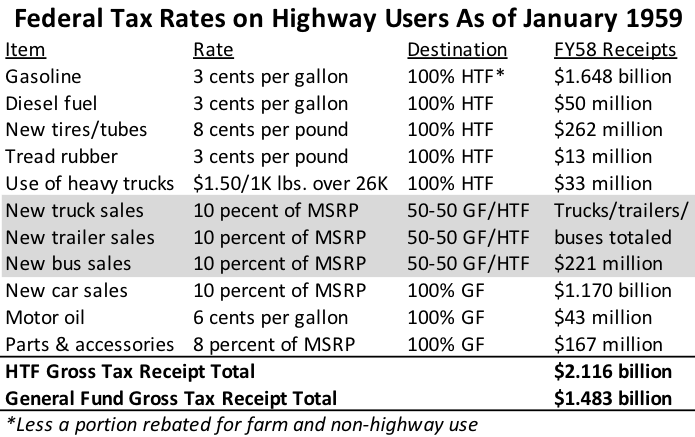

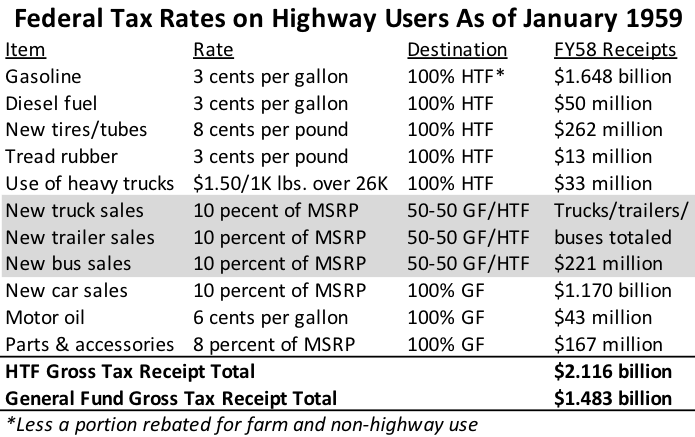

At those initial Senate Public Works hearings in February 1959, several Senators began a line of questioning that was to last all year (pushed by states and by highway stakeholder groups): was it really necessary to increase taxes on highway users, when Congress could just as easily transfer existing highway user taxes, currently deposited in the general fund, to the Highway Trust Fund? Highway users had paid $3.6 billion in federal excise taxes in fiscal year 1958 on the machines they drove, their parts and tires and accessories, the fuel they used, and the oil that kept their engines lubricated (along with a special usage tax on trucks over 26,000 pounds). Only about 60 percent of that money was deposited in the Highway Trust Fund – the rest remained as part of general revenues.

In the House, future Republican Leader Bob Michel (R-IL), then a back-bencher starting his second term in Congress, had already introduced a bill on February 11 transferring half of the 10 percent automobile tax to the Trust Fund in lieu of any gas tax increase and inserted a speech against the gas tax increase into the Record.[20]

But any diversion of the existing general fund taxes – the remaining half of the truck, trailer and bus taxes or any part of the automobile sales tax or motor oil and parts taxes – would throw the entire federal budget out of balance, since those revenues would be withdrawn from the estimated $77.1 billion in 1960 tax receipts that were measured against the $77.0 billion in spending to determine the federal deficit per the administrative budget (excluding trust funds). At the February hearings, Sen. Francis Case (R-SD), the ranking Republican on Public Works, said:

“Looking at the thing realistically, my conclusion as of today would be this: No. 1, that Congress will not increase the Federal gasoline tax; No. 2, that the President would be disposed to veto any proposal to make up the so-called deficit by direct appropriation, out of the General Treasury in view of the total budget situation, and, No. 3, that the President would also regard any allocation of additional excise taxes in the same way that he would direct appropriations from the Treasury.

“The Governors have been pointing to the revenues from the automobile excise tax and some other taxes of which only 50 percent would be in the trust fund.

“The Budget Bureau and the President, in my opinion, would be disposed to regard further allocation of those excise taxes in the same light as they would a direct appropriation. For if those revenues would be assigned to the trust fund, other revenues or other borrowing would be required to provide the funds for the Treasury.”[21]

Case had also apparently been talking to the Bureau of Public Roads, which had its own proposal. Several days before the Public Works hearings, on February 24, 1959, an internal Budget Bureau memo said that the HTF revenue bonding proposal that Bert Tallamy at Public Roads had prepared in mid-December 1958 was now making the rounds again – (the author of the Budget memo said that the proposal “attributed to General [Lucius] Clay would authorize the Highway Trust Fund to borrow against future receipts from presently earmarked taxes the estimated $3.9 billion required to cover apportionment of authorized funds through 1964. These borrowings, plus interest would be repaid from revenues after 1972 when construction is completed…This is essentially a 1959 model of the original 1955 Clay proposal…”[22] The memo went on to say that the plan was contrary to Congress’s rejection of bonding in 1955, contrary to the President’s signing statement of the 1958 Act, would incur tremendous long-term borrowing costs, and would outrage Senate Finance Committee chairman Harry Byrd (D-VA).

During the February 27 Public Works hearing, Senator Case said that he thought HTF revenue bonds were the best alternative (though he never mentioned that BPR was pushing the plan). The following Monday (March 2), Tallamy and Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation John J. Allen were meeting with the head of the Bureau of the Budget and his staffers, and during that meeting, Budget asked about the bonding plan and Budget Director Maurice Stans asked to see a copy.[23]

The revenue bond plan sent to Budget and then circulated to the Treasury Department, which stomped on it with both feet. Under Secretary of the Treasury Julian Baird sent a short letter to Commerce Secretary Strauss on March 10, saying that “having offerings of several billion dollars of additional Government securities competing in the market with our direct Treasury financing over the next few years” was a problem for Treasury. Baird also endorsed the conclusion of a Treasury staff memo he forwarded which warned that issuing bonds instead of raising taxes would take billions of dollars out of the American capital investment pool, not the broader economy, and thus injure the investment rate and the economic growth rate. Baird told Strauss that the latter seemed to him to be “an argument that should be effective with a good many members of the Congress.”[24]

On April 7, Budget Director Stans sent the Commerce Secretary a reply letter saying that Treasury and Budget jointly agreed that “the issuance of such bonds would be most unwise and that the President’s proposal for increases in highway taxes represents the soundest and most logical method of financing the highway program, both currently and over the longer period.”[25]

But Senator Case did not give up – he eventually had the Bureau of Public Roads draft implementing legislation for the HTF revenue bond proposal which he introduced on his own (S. J. Res. 109, 86th Congress) in June. (The full text of all of the iterations of the bonding proposal can be downloaded here.)

The Eisenhower Administration was slow in submitting its draft tax legislation to Congress (they didn’t even decide whether Commerce or Treasury was to write the bill until March 9, 1959), so the new chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee took the initiative.

Wilbur Mills takes the lead

Rep. Wilbur Mills (D-AR) became chairman of the Ways and Means Committee halfway through the 85th Congress, in January 1958, following the death in December 1957 of the previous chairman, Jere Cooper (D-TN). On March 31, 1959, Mills telephoned the Treasury Department and asked to speak to the Secretary. Upon hearing that Secretary Anderson was out of town, he wound up talking with Under Secretary Baird for a half-hour about the Highway Trust Fund.

In a memo to the Secretary recounting the conversation, Baird wrote that Mills “said the suggestion had come to him that [the Trust Fund] could be financed by having the Trust Funds borrow and pay off by extending the period in which taxes were levied from 1972 to 1978…I had an opportunity to make all the points against borrowing for the deficit which you and I have discussed.”

Mills then “told me, as he had told you previously, that he ruled out the gasoline tax as he believed that, with the increasing utilization of that tax by the States in addition to the Federal levy, too large an element of tax was being concentrated in one commodity. I told him that I was sure you had no fixation on the precise tax that would be levied to maintain the program on a ‘pay-as-you-go’ basis and that the purpose should be to find some temporary tax that would fill the gap until the results of the 1961 study on possible revenue sources were determined.”[26]

Baird then brought up “the possibility of an addition to the license tax on motor vehicles,” which he said got some traction with Mills, and Baird later ordered Treasury’s Office of Tax Analysis to come up with some ideas. Treasury staff responded on April 6 with a memo exploring possible ways for the federal government to levy an annual vehicle tax, including a flat, per-vehicle tax (as had been levied during WWII at $5 per vehicle per year), a tax on value, or a tax based on some kind of physical characteristics of the vehicle (such as horsepower, weight, length or width).[27] They followed up with a more refined memo on May 22 that only discussed a flat fee, a weight tax, or a value tax and determined that while a weight tax would bear the most resemblance to a tax on road use, federal administration of any vehicle tax was going to be seriously problematic.[28]

(The Commerce Department had been working on this separately – a March 27 memo from the Bureau of Public Roads gave estimated revenues that could be generated by a “Federal vehicle license tag or windshield sticker” which, the memo said, “has been proposed at various times by Senator Case and others.”[29] Like the Treasury study, BPR said the problems were all about compliance and enforcement.)

Treasury wrote to Mills on May 6 in opposition to diverting any of the existing auto or auto parts taxes from the general fund to the HTF, in response to a bill that had been introduced in this regard by Rep. Victor Knox (R-MI) (H.R. 3658, 86th Congress).[30] But despite the warning, by mid-month, Mills was floating his own proposal for HTF solvency – diversion from the general fund to the Trust Fund of all of the tax on auto parts and accessories and half of the tax on new car sales, coupled with a one-year extension of the life of the Trust Fund and its taxes (from 1972 to 1973). The Treasury Department estimated that this would divert an average of $885 million in tax receipts per year starting in 1961 from the general fund to the Highway Trust Fund, and would still require annual temporary bailout transfers from the general fund ($206 million in FY 1962 and lesser amounts in 1963 and 1964).[31]

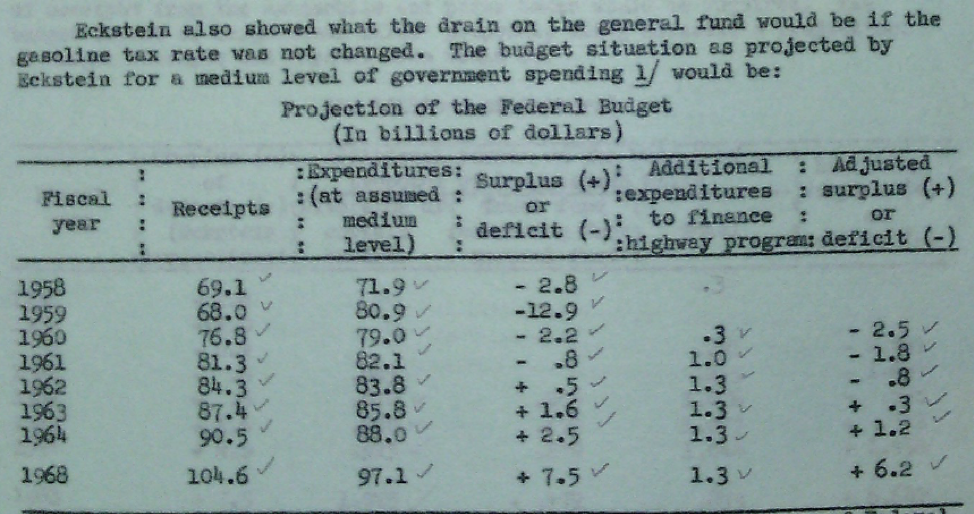

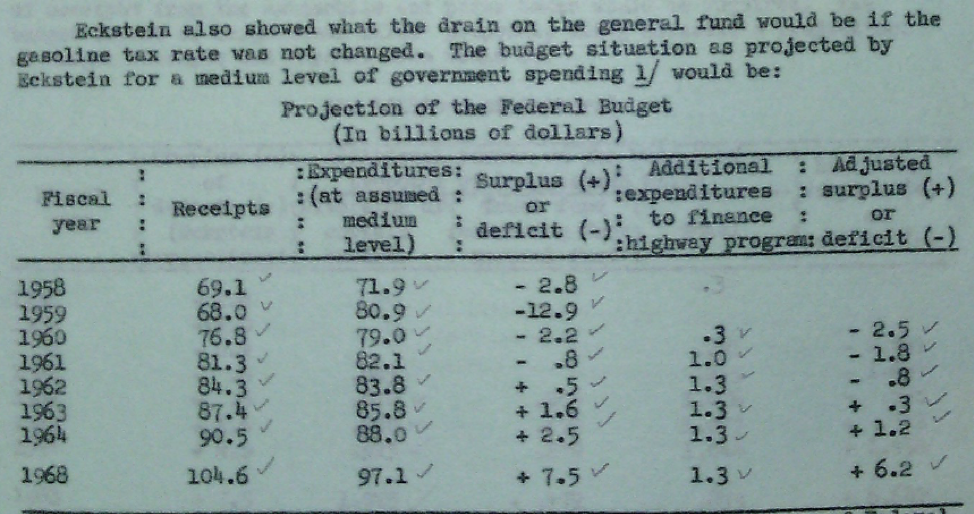

Administration opposition to any diversion or borrowing from the general fund was strengthened in mid-May by a long-term analysis of the budget published by famous Harvard economist Otto Eckstein. Eckstein’s analysis showed that the federal budget would be balanced by FY 1962 unless the general fund were tapped to support highway overages, in which case “the administrative budget would not show a significant surplus until 1964.”[32]

The President sends up his own bill

Meanwhile, the Eisenhower Administration had sent up its proposed gas tax increase legislation on April 3 – a five-year (July 1, 1959 – June 30, 1964) increase in the gasoline tax from 3 cents per gallon to 4 ½ cents per gallon, plus equalization of the taxation of aviation gasoline and jet fuel and the deposit of those taxes in the general fund, not the HTF, to help defray air traffic control expenses. The cover letter from the Treasury Department to Congress noted that If the proposed increase is not adopted, the highway program, in the absence of further Congressional action, automatically will be curtailed.”[33]

At an April 28 White House meeting with GOP legislative leaders, new Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL) and new House Minority Leader Charlie Halleck (R-IN) “noted the opposition to the President’s proposal…Dirksen believed the program needed a complete reappraisal since the estimated cost now so far exceeds the original estimates. Otherwise he feared there would be pressure for deficit financing rather than maintaining the ‘pay as you go’ basis. Mr. Halleck mentioned a suggestion for applying the 10% automobile excise to the highway program. He felt this would be unacceptable, particularly as related to the railroads where the excise goes into general funds. He thought that perhaps favorable sentiment for the gasoline tax would soon develop.”[34]

After Acting Commerce Secretary Strauss pointed out that “the alternative to an increase in the gas as being either the use of general funds or curtailment of the program,” President Eisenhower “called attention to the great need for catching up on the building of roads. He recalled the 1955 decision to conduct this program rapidly and he saw the need for new roads as being as great now as ever. He said he would be dismayed at the prospect that the present problem might be solved by stopping the whole program in its tracks, for this program was also a very beneficial thing to the economy, and he would like to stick to the decision to get it accomplished in 13 years. He believed the question merited the very serious consideration of anyone who might be tempted to vote for a stoppage.”[35]

The next day, Dirksen wrote a letter to Budget Director Stans about growing unrest relating to the pending highway apportionment cutoff, saying that “Already State Highway Departments are in contact with members of the House and Senate, and I presume as we move to July 1, there will be a great deal of agitation.” He suggested a series of possible options, including “A real appeal could be made for enactment of the proposed gas tax increase, although I must say from all that I could see that the prospect of having this enacted looks rather slender at the moment.”[36]

Stans responded to Dirksen with a letter stating that “we are convinced that a fuel tax increase is the soundest solution at this time. We would prefer to make every attempt to get this enacted and to avoid suggesting alternatives. As you know, the President is considering a special message or other communication urging enactment of the legislation submitted by the Secretary of the Treasury.”[37] The letter also rejected further Byrd Test suspension as unwise, said that diverting general fund taxes to the Trust Fund as being “even worse than waiving the Byrd amendment,” and said that other ideas suggested by Dirksen would not solve the immediate problem.

At a May 5 White House news conference, President Eisenhower had the following exchange with a Scripps-Howard correspondent, Lowell Bridwell (who would go on to become Federal Highway Administrator himself under Lyndon Johnson):

“Q. Lowell K. Bridwell, Scripps-Howard: There are some indications that the Congress is rather reluctant to pass the penny-and-a-half-per-gallon gasoline tax increase which you requested, and instead, is showing some signs of wanting to transfer excise taxes from the general fund to a highway trust fund in order to keep the highway program going. Would you comment?

“THE PRESIDENT. I think that everything that we need to do in this country, we ought to pay for.

“They are talking now about, saying, “Well, we’ll continue to build roads.” But by this method that you describe, you would not be paying for other programs which the Congress obviously feels to be essential.

“So, if they don’t want to put in the cent-and-a-half additional tax on gasoline that I think is necessary to carry forward this road program effectively, then they ought to find the revenue to make good the deficits they would create in the general fund.”[38]

In the face of continued Congressional inaction, the President sent a special message to Congress on May 13 asking them to hurry up and address three time-sensitive programs: highways, home mortgage insurance aggregate ceilings, and reducing the buildup of surplus wheat. With regard to highways, he warned that “it will be impossible this year, without Congressional action, to apportion funds so that States may make commitments for future highway construction” and opposing both a diversion of auto excise taxes and a proposed Byrd Test waiver as fiscally unsound. And he pointed out that states were expecting their new 1961 highway apportionments in less than two months.[39]

When Eisenhower’s message was read before the Senate that day, Minority Leader Dirksen urged action. Sen. Richard Neuberger (D-OR), a member of the Public Works Subcommittee on Roads, agreed with Eisenhower’s position, saying that “Some 34 Governors of States, both of the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, have exerted strong pressure on the subcommittee not to authorize the increase in the motor fuels tax which the President has recommended…They claim the motor fuels tax should be left to the States. I do not see how that position can be taken when the States are perfectly willing to accept from the Federal Government 90 percent of the payment of the costs of the most expensive roads ever built anywhere in the United States.”[40]

Response to the message was negative amongst Democrats. Speaker Sam Rayburn said that the message “looks to me like a purely political document” and said that if any Republicans in the House were supporting the gas tax increase, then one of them would have introduced the President’s bill in the House by that point (none had).[41] Ways and Means chairman Mills responded “I said in January I was opposed to the increase, and I have seen nothing to change my mind,” and Senate Majority Whip Mike Mansfield (D-MT) said that passage of the tax increase “would not be forthcoming.”[42]

(The Administration finally persuaded Rep. Howard H. Baker (R-TN) to introduce the President’s 1.5 cent gas tax increase on June 24 as H.R. 7939, 86th Congress. Baker’s son and namesake would go on to shepherd the next (post-1959) gas tax increase through Congress as Senate Majority Leader under President Reagan in 1982.)

Eisenhower held another press conference shortly after his special message was sent up on May 13 where he told the Washington Star that “we ought to continue the road program, because of is great necessity, and we ought to pay for it.”[43]

But despite the high-profile presidential nudging, which was well-reported in national newspapers, there was still no action in Congress on the revenue problem. At the regular meeting with GOP Congressional leaders at the White House on May 28, Eisenhower stressed repeatedly the importance of providing funds for carrying on the highway program” and asked staff for a paper that would quantify the economic impact of shutting down the highway program. But both House Minority Leader Halleck and Rep. Leo Allen (R-IL), the ranking minority member on the House Rules Committee, “felt that it would be impossible to obtain an increase in the gasoline tax, hence the probability that the program would have to be cutback.”[44]

In response, the House Public Works Committee approved a bill (H.R. 5950, 86th Congress) on May 21 to suspend the Byrd Test for both fiscal 1961 and 1962 (necessitating borrowing from the general fund of over $2 billion by the end of 1962) and increasing the 1962 authorization for Interstate Construction from $2.2 billion to $2.5 billion and approving the cost estimate for those years. But Public Works could not file the report on the bill and move it to the House floor because they had no way to pay for it, so they had to wait for the Ways and Means Committee, which still had not reached a consensus.

The Administration squeezes the states

By this point, the scheduled Congressional session was more than half over, and the White House was growing anxious to find a way to get state governments and highway stakeholders to back away from their opposition to the proposed gas tax increase. Increasing the public knowledge of when the stream of contract authority would run out, for each state, was one way to apply pressure.

Per the President’s request for more detailed information about how, where and when the effects of the funding cutoff required by the Byrd Test would be felt, Federal Highway Administrator Tallamy sent identical telegrams to the heads of the road agencies in each of the 50 states in early June asking them “Assuming there will be no 1961 Interstate apportionment and a maximum of only $500 million for 1962, based on best current information and your normal schedule of contract letting, at which approximate date would you have to stop awarding Interstate construction contracts?”[45]

The collection of response telegrams was appended to a report by Tallamy sent to the President on June 23 giving a brief overview of the Trust Fund revenue situation, the Byrd Test, and where the states stood. Most immediately, “during the next three months, ten States will be unable to award further Federal-aid Interstate contracts. These are: California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Oregon and Vermont.”[46] Sixteen more states and the District of Columbia would have to shut down all new contracts by July 1960.

The White House promptly released Tallamy’s report to the press along with a statement from the President that “The only serious alternatives now being considered by the Congress – waiving the Byrd “pay-as-you-go” Amendment or diversion of other taxes – would solve nothing. They would either increase the size of the Highway Fund deficit by further postponing the pay-as-you-go principle, or reduce the general revenues available for other essential programs. Either of these alternatives would be unacceptable to me…This is a critical situation in our national road-building program, and one which should give greater concern to every motorist. We are on the verge of a stalemate in the orderly development of our vital Interstate road network.”[47] (The report is printed in the Congressional Record starting at page 11852 here.)

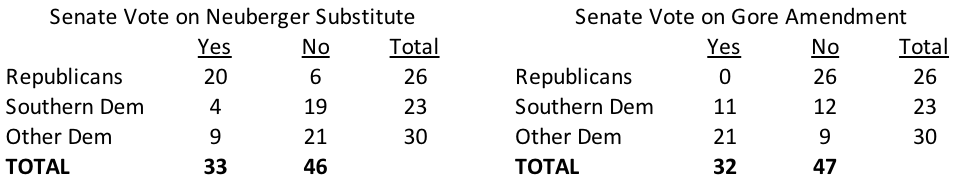

The release of this report did prompt Congressional action, of a kind. On the morning of June 25, Dirksen had the President’s new message read to the Senate. Later that day, the Senate was in the process of debating an unrelated tax bill (H.R. 7523, 86th Congress). Senator Al Gore (D-TN), a key author of the 1956 and 1958 highway acts, offered an amendment to transfer all of the excise taxes on automobiles, trucks, buses, parts and accessories to the Highway Trust Fund and transfer half of the lubricating oil tax as well. He then modified his amendment so the Trust Fund would only get 50 percent of the tax on new cars and motor oil but 100 percent of the tax on trucks, trailers and buses and 100 percent of the parts and accessories tax.

Gore said “I want to be perfectly candid with the Senate. As I see it, we have three choices: One, to let this program stop. Two, to earmark additional revenue from highway user taxes to the fund. Or, three, pass a bill increasing the gas tax by 1½ cents, as the President has recommended. Senators can take their choice. As for me, I have made my choice, which I am ready to recommend to the Senate. There is more than 1½ billion in annual revenue from highway user taxes which is not earmarked or dedicated to the highway trust fund…I do not think it would be fair to levy an additional burden on the people who make their living from our highways, until we use for highway purposes the revenue from highway user taxes we already have.”[48]

Gore’s amendment would have diverted $964 million in FY 1960 from the general fund to the Trust Fund, which, under the budget concepts used at the time, would increase the federal deficit by that same amount (since trust funds were effectively off-budget). Dirksen responded that “If ever I saw an invitation to a veto, it is tonight. If I were sitting in the Presidential chair, I would not have to say it twice or think about it twice. I would know what I would do when I read the headlines and learned that the Senate had approved the blowing of a $964 million hole in the budget, because $964 million is certainly nuclear in my book.”[49]

Richard Neuberger then offered a substitute version of the Gore amendment which struck all of Gore’s provisions and instead added the President’s requested 1.5 cent per gallon motor fuel tax increase (but only for two years). He said “I do not see how we can take nearly $1 billion out of the budget and put it into the highway trust fund, without leaving an enormously large hole in the budget. If we were to do that, we would merely be robbing Peter to pay Paul. I believe it makes sense to increase the Federal motor fuels tax sufficiently to pay for these roads as we go. In all the States there is a motor-fuel tax, and it is dedicated to highway construction. It seems to me that in this particular situation the President has been correct in his recommendation. There are many occasions when I do not agree with the President. But when he is right, it seems to me I would be foolish to let partisanship blind me to the fact that he is right.”[50]

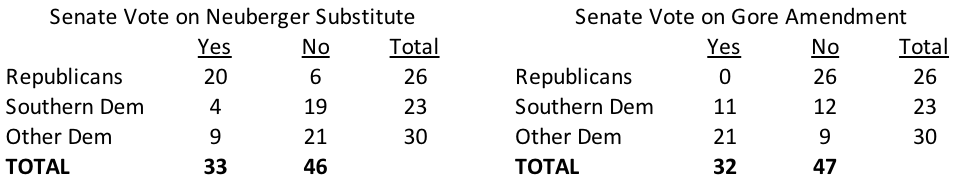

The votes were held later that evening, and were almost identical, with Neuberger getting one more “yes” vote than Gore had, but both proposals still failing badly:

(This being the 1950s, we are using the old Congressional Quarterly method of distinguishing Southern Democrats (those from the 11 states of the Confederacy, plus Oklahoma and Kentucky) because of how differently they often voted from other Democrats back then.)

18 Senators voted “no” on both plans (eight Southern Democrats, five other Democrats, and five Republicans).

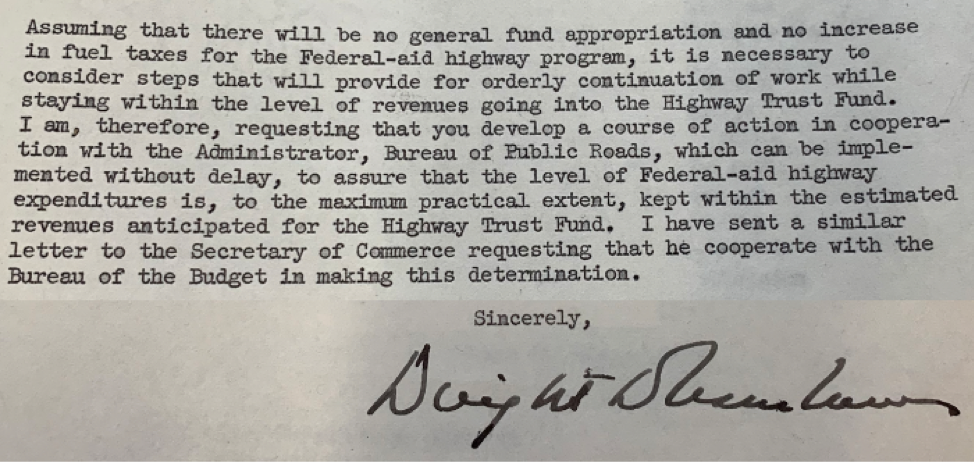

The pending shutoff of new contract authority apportionments did get some attention in Congress, but it would only force ten states to shut down new contracts within three months, which meant that 40 other states would still be able to carry on business as usual for up to two years. Something more immediate was needed to pressure those states, so on June 23, the White House Budget Bureau was having its own internal meeting to discuss a strategy for getting to those states. According to the memo from the Commerce and Financing Division to Director Stans, the strategy involved getting President Eisenhower to instruct Budget and Commerce to conduct a study of how to keep Trust Fund outlays from exceeding balances if Congress failed to act. Budget would then cite the President’s letter as justification for asking Commerce to “take immediate steps to slow down highway obligations and expenditures” and then, possibly, having the Commerce Secretary write to the governor of each state of how Commerce was doing to slow down their spending.[51]

The memo asked a political question:

“The basic question is whether we would gain or lose by notifying State Governors now of the steps which may have to be taken to avoid a deficit in the Highway Trust Fund, e.g., an expenditure ceiling for each State. The letter would put us in a better position to take stern measures immediately, but it will produce considerable alarm on Capitol Hill. The net effect on Congress could be to increase chances for enactment of additional motor fuel taxes, but it could also mean increased support for waiving the Byrd amendment regardless of a probable veto or diverting additional excises to the Highway Trust Fund. If it is decided to recommend sending such a letter, our attached draft could be given to Commerce informally.”

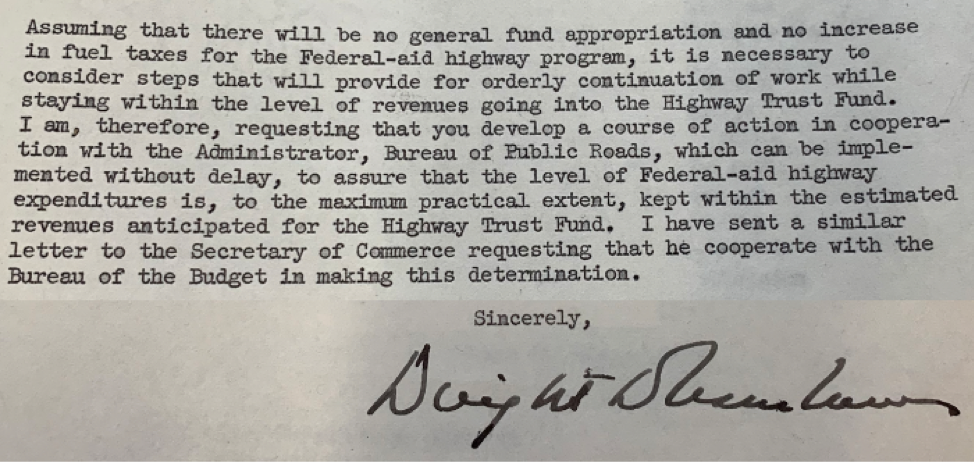

President Eisenhower sent nearly identical letters to the Commerce Secretary and the Budget Director on July 2, the nutshell of which was this (taken from the letter to Budget Director Stans):

“Assuming that there will be no general fund appropriation and no increase in fuel taxes for the Federal-aid highway program, it is necessary to consider steps that will provide for orderly continuation of work while staying within the level of revenues going into the Highway Trust Fund. I am, therefore, requesting that you develop a course of action in cooperation with the Administrator, Bureau of Public Roads, which can be implemented without delay, to assure that the level of Federal-aid highway expenditures is, to the maximum practical extent, kept within the estimated revenues anticipated for the Highway Trust Fund.”[52]

In response to that letter, a meeting was held on July 9 between Budget, Commerce, and BPR where the group “concluded that the President’s letter meant that in the absence of any increase in revenues there would be no Administration request for a deficiency appropriation in this session to meet the anticipated deficit in the Trust Fund during the first half of this fiscal year…This would mean that some means would have to be developed during the next few weeks to curtail current expenditures amounting to around $300 million.”[53]

BPR’s Tallamy “suggested that the only feasible way of saving large sums immediately would be to curtail expenditures on right of way” but Budget suggested more expansive measures like delaying non-Interstate apportionments until December 31 and delaying non-ROW project approvals. The meeting summary memo notes that “Some discussion took place over the political effect of such a retrenchment policy in the Congress, involving accusations of pressure tactics.”[54] The lawyers of the various agencies were ordered to come up with a solid legal rationale of whether contract authority and its use could be curtailed, absent legislation.

The Executive Secretary of the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) sent a notice to all member states on July 6 saying that “In case there were enough additional money found to eliminate the deficit in the Trust Fund for 1960, we would have no problem but it seems unlikely that there will be enough new taxes enacted to eliminate the deficit and at present it appears unlikely that the Administration will consent to drawing any money from the general treasury in the form of repayable advances…”[55] The notice also said that AASHO had requested clarification from the Bureau of Public Roads.

Tallamy responded with a letter to AASHO indicating that the Budget Bureau’s hard line had won out. He told AASHO that not only would apportionments of new contract authority for the Interstate System be shut off until the Trust Fund’s projected deficits were eliminated, a “moratorium on new contracts and right-of-way purchases” would have to begin soon and “would have to continue until the spring of 1960, at which time new contracts could be started and right-of-way purchases resumed against existing apportionments but at a reduced rate.”[56] (Emphasis added.)

Even worse, not only would new contracts and purchases be suspended, states would soon be forced to wait for weeks or months for repayment of costs they had already incurred: “Unless the income of the trust fund is increased, State vouchers for both ABC and Interstate System reimbursements, of about $500 million, will have to be held unpaid until the trust fund receipts exceed expenditures. The holding of vouchers would have to begin this fall.”[57] (Emphasis added.)

If this didn’t put state governments into panic mode, nothing would.

Concluded in part 3 with the story of Congressional actions and showdowns, the first general fund bailout, the enactment of a temporary gas tax increase (later made permanent), and the imposition of the first highway contract controls on states.

[1] Letter from Dan Throop Smith (Deputy to the Secretary of the Treasury) to the Secretary of Commerce, dated July 2, 1958. Located in the “DC2 Highway Trust Fund 1956-1972” folder in Box 8 of the Office of Tax Policy – Subject Files in the General Records of the Department of the Treasury in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[2] Letter from Dan Throop Smith (Deputy to the Secretary of the Treasury) to the Secretary of Commerce, dated October 15, 1958. Located in the “DC2 Highway Trust Fund 1956-1972” folder in Box 8 of the Office of Tax Policy – Subject Files in the General Records of the Department of the Treasury in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[3] Letter from Russell E. Singer to Robert B. Anderson dated November 19, 1958. Located in the folder “DC2 Highway Material – 1958-1960” in Box 7 of the Office of Tax Policy – Subject Files in the General Records of the Department of the Treasury in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[4] Memo from Mr. Leahey to Dan Throop Smith dated November 26, 1958 with the subject line “Highway Trust Fund.” Located in the “DC2 Highway Trust Fund 1956-1972” folder in Box 8 of the Office of Tax Policy – Subject Files in the General Records of the Department of the Treasury in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[5] Memo from P.L. Sitton to Budget Director Stans with the subject line “Cabinet discussion of Federal-aid highway program” dated December 1, 1958. Located in the “P2-7/3 Budget and Financing to 1959” folder in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[6] Letter from the Acting Secretary of Commerce to the Budget Director dated December 2, 1958 memorializing a December 1 meeting. Located in a manila envelope labeled “P2-7/3 Sr. 52.1” in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[7] Bertram Tallamy draft letter (with attachment) to the Director of the Bureau of the Budget dated December 11, 1958. Located in the “Highways – Financing – Legislative Branch Matters, 1958, Jan. Feb. March and April 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records (Relating to the Transportation Study) 1955-1963 of the Office of the Under Secretary of Transportation of the Department of Commerce at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[8] United States. President and Council of Economic Advisers (U.S.). “1959,” Economic Report of the President (1959) p. iii. Retrieved online from https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/45/item/8130 on August 26, 2019.

[9] U.S. Congress. Joint Economic Committee. “1959 Joint Economic Report” (Report by the JEC on the January 1959 Economic Report of the President) printed as Senate Report 98, 86th Congress, 1st session p.56

[10] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Statement by the President on the Budget for Fiscal 1960. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, retrieved August 24, 2019 from https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/234460

[11] Budget of the United States Government for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1960, pp. M11-M12. Retrieved online August 24, 2019 from https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/usbudget/bus_1960.pdf

[12] Sita Nataraj and John B. Shoven. “Has the Unified Budget Undermined the Federal Government Trust Funds?” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 10953, December 2004, p. 6. Retrieved online August 26, 2019 at https://www.nber.org/papers/w10953.pdf

[13] Associated Press, published in the Washington Post as “29 Governors Oppose Gasoline Tax Increase,” January 26, 1969 p. B6.

[14] AP story published (among other places) as “Window on Washington: Senator Cites Opposition in States to Increase Federal Gasoline Tax” in the Hartford Courant, January 18, 1959 p. 8A.

[15] Gerald Griffin, “Democrats Rap Budget on 3 Fronts,” Baltimore Sun, January 21, 1959, p. 1.

[16] Congressional Record (bound edition), January 20, 1959 p. 862.

[17] Ibid pp. 863-864.

[18] From U.S. Senate. Committee on Public Works. “Status of Public Roads, 1959” (Hearings on Status and Progress of the National Highway Program, 1959, February 26 and 27, 1959), 86th Congress, 1st Session p. 45.

[19] Financial Condition and Results of the Operations of the Highway Trust Fund, Fiscal Year 1958 (Letter from the Acting Secretary of the Treasury Transmitting the Third Annual Report on the Financial Condition and Fiscal Operations of the Highway Trust Fund for the Fiscal Year 1958, Pursuant to Section 209(e)(1) of the Highway Revenue Act of 1956), March 2, 1959. Printed as House Document No. 92, 86th Congress, 1st Session.

[20] Congressional Record (bound edition), February 11, 1959 p. 2194.

[21] U.S. Senate. Committee on Public Works. “Status of Public Roads, 1959” (Hearings on Status and Progress of the National Highway Program, 1959, February 26 and 27, 1959), 86th Congress, 1st Session p. 29.

[22] Bureau of the Budget internal memo from Commerce-Finance Division (Reeve) to The Director with subject line “Commerce proposal for borrowing against future Highway Trust Fund revenues” and dated February 24, 1959. Located in a manila envelope labeled “P2-7/3 Sr. 52.1” in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[23] Memo from Bertram Tallamy, Federal Highway Administrator to Commerce Secretary Lewis Strauss dated March 3, 1959. Located in the “Highways – Financing – Legislative Branch Matters, 1958, Jan. Feb. March and April 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records (Relating to the Transportation Study) 1955-1963 of the Office of the Under Secretary of Transportation of the Department of Commerce at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[24] Letter from Julian Baird (Treasury Department) to Commerce Secretary Lewis Strauss dated March 10, 1959. Located in the “Highways – Financing – Legislative Branch Matters, 1958, Jan. Feb. March and April 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records (Relating to the Transportation Study) 1955-1963 of the Office of the Under Secretary of Transportation of the Department of Commerce at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[25] Letter from Budget Director Maurice Stans to Commerce Secretary Lewis Strauss dated April 7, 1959. Located in the “Highways – Financing – Legislative Branch Matters, 1958, Jan. Feb. March and April 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records (Relating to the Transportation Study) 1955-1963 of the Office of the Under Secretary of Transportation of the Department of Commerce at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[26] Memo from Under Secretary Julian Baird to Secretary Robert Anderson dated March 31, 1959 with the subject line “Conversation with Congressman Mills re Financing Interstate Highway Program.” Located in the folder “DC2 Highway Material – 1958-1960” in Box 7 of the Office of Tax Policy – Subject Files in the General Records of the Department of the Treasury in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[27] U.S. Treasury Department, Tax Analysis Staff. “Annual Fee for Highway Vehicles” dated April 6, 1959. Located in the folder “DC2 Highway Material – 1958-1960” in Box 7 of the Office of Tax Policy – Subject Files in the General Records of the Department of the Treasury in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[28] U.S. Treasury Department, Tax Analysis Staff. “Annual Fee for Highway Vehicles for Highway Trust Fund Purposes” dated May 22, 1959. Located in the folder “DC2 Highway Material – 1958-1960” in Box 7 of the Office of Tax Policy – Subject Files in the General Records of the Department of the Treasury in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[29] Memo from F.C. Turner, Deputy Commissioner of Public Roads, to Commerce Under Secretary John J. Allen, Jr., dated March 27, 1959 with the subject line “Possible Yields from Proposed Taxes.” Located in the “Highways – Financing – Legislative Branch Matters, 1958, Jan. Feb. March and April 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records (Relating to the Transportation Study) 1955-1963 of the Office of the Under Secretary of Transportation of the Department of Commerce at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[30] Letter from David A. Lindsay, Assistant to the Secretary of the Treasury, to Rep. Wilbur Mills dated May 6, 1959. Located in the “KB 1941-1972 Motor Vehicles” folder in Box 10 of the Office of Tax Policy – Subject Files series in the General Records of the Department of the Treasury at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[31] U.S. Treasury Department, Tax Analysis Staff. “Projection of the Federal Budget and impact of the highway program” dated May 12, 1959. Located in the folder “DC2 Highway Material – 1958-1960” in Box 7 of the Office of Tax Policy – Subject Files in the General Records of the Department of the Treasury in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[32] Memo from Mr. Eldridge to Treasury Secretary Anderson with the subject line “Projection of the Federal Budget and impact of the highway program” dated May 14, 1959. Located in the “DC2-7/3 Highway Material 1957-1960” folder in Box 7 of the Office of Tax Policy – Subject Files series of the General Records of the Department of the Treasury at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[33] Letter from the Acting Secretary of the Treasury to the President of the Senate, April 3, 1959. Located in the “Sen. 86A-F7 Revenue – Excise – Gasoline” folder in Box 11 of the Committee on Finance – Revenue series of the Records of the U.S. Senate at the National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[34] L.A. Minnich, Jr. “Notes on Legislative Leadership Meeting – April 28, 1959” pp. 3-4. Located in the “Legislative Meetings 1959 (3) [March-April]” folder in Box 3 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Papers as President (Ann Whitman File) 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[35] Ibid p. 4.

[36] Letter from Everett McKinley Dirksen to Maurice H. Stans dated April 29, 1959. Located in a manila envelope labeled “P2-7/3 Sr. 52.1” in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[37] Draft letter from Maurice Stans to Everett Dirksen dated May 5, 1959. Located in a manila envelope labeled “P2-7/3 Sr. 52.1” in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[38] Dwight D. Eisenhower, The President’s News Conference (May 5, 1959). Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project and retrieved August 28, 2019 at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/235599

[39] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Special Message to the Congress Urging Timely Action Regarding the Highway Trust Fund, Housing, and Wheat (May 13, 1959). Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project and retrieved August 28, 2019 at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/234841

[40] Congressional Record (bound edition), May 13, 1959, p. 8047.

[41] John D. Morris, “President Prods Congress, Roads, Wheat,” The New York Times, May 14, 1959 p. 1.

[42] “President Scores Congress Democrats for ‘Inaction’ on Administration’s Highway, Housing, Wheat Plans,” The Wall Street Journal, May 14, 1959 p. 3.

[43] Dwight D. Eisenhower, The President’s News Conference (May 13, 1959). Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project and retrieved August 28, 2019 at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/234825

[44] L.A. Minnich, Jr. “Notes on Legislative Leadership Meeting – May 26, 1959.” Located in the “Legislative Meetings 1959 (4) [May-June]” folder in Box 3 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Papers as President (Ann Whitman File) 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[45] Text of telegram, retyped, located in the “86A-D13 HR 8678 3 of 5” folder in Box 462 of the Papers Accompanying Bills and Resolutions – Committee on Ways and Means, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, 86th Congress at the National Archives, Washington D.C.

[46] Bertram Tallamy, “Report on the Interstate System Program,” June 23, 1959 p. 2. Located in the “OF 141-B Highways and Thoroughfares (Roads) (21)” folder in Box 612 of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Records as President, White House Central Files, 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[47] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Statement by the President (undated but with “For Release in Thursday Morning Papers, June 25, 1969” at the top, implying the date was June 24 or earlier. Located in the “OF 141-B Highways and Thoroughfares (Roads) (21)” folder in Box 612 of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Records as President, White House Central Files, 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[48] Congressional Record (bound edition), June 25, 1959 p. 11938-11939.

[49] Ibid p. 11941.

[50] Ibid p. 11947.

[51] Memo from the Bureau of the Budget Commerce and Finance Division to the Director with the subject line “1960-1961 Federal-aid Highway Funding Problem” dated June 23, 1959. Located in a manila envelope labeled “P2-7/3 Sr. 52.1” in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[52] Letter from Dwight D. Eisenhower to Maurice H. Stans dated July 2, 1959. Located in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[53] Memo from Byron Nupp to the Under Secretary of Transportation dated July 9, 1959 with the subject line “Meeting with Bureau of the Budget concerning short range financing of the Federal Aid Highway Program.” Located in the “Highway – Financing – Legislative Branch Matters, May, June, July 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records (Relating to the Transportation Study) 1955-1963 of the Office of the Under Secretary of Transportation of the Department of Commerce at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Letter from A.E. Johnson, AASHO Executive Secretary, to complete member list, July 6, 1959. Copy found in the Located in the “Highway – Financing – Legislative Branch Matters, May, June, July 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records (Relating to the Transportation Study) 1955-1963 of the Office of the Under Secretary of Transportation of the Department of Commerce at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[56] Letter from Bertram D. Tallamy to A.E. Johnson dated July 10, 1959. Located in the “Highway – Financing – Legislative Branch Matters, May, June, July 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records (Relating to the Transportation Study) 1955-1963 of the Office of the Under Secretary of Transportation of the Department of Commerce at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. See also July 13, 1959 memo from Under Secretary for Transportation to Administrator, BPR in the same folder for clarification on the send date.

[57] Ibid.